November 10, 1981

What is the fact of cinematographic perception? It’s that movement is not added to the image. Movement does not get added to the image. There is no image, and then movement. In the artificial conditions that Bergson has well determined, what is presented by cinema is not an image to which movement would be added. It is a movement-image — with a little hyphen, with a little dash — it is a movement-image. Of course, this is reproduced movement, that is, reproduced movement, I tried to say what that meant. That means: perception of movement, or synthesis of movement. It’s a synthesis of movement. Only here we are, when I say movement is not added to the image, I mean the synthesis is not an intellectual synthesis. It is an immediate perceptual synthesis, which captures the image as a movement, which captures in one the image and the movement, that is, I perceive a movement-image. To have invented the movement-image is the act of creating cinema.

Seminar Introduction

In the first year of Deleuze’s consideration of cinema and philosophy, he develops an alternative to the psychoanalytic and semiological approaches to film studies by drawing from Bergson’s theses on perception and C.S. Peirce’s classification of images and signs. While he devotes this first year predominantly to what he considers to be the primary characteristic of cinema of the first half of the 20th century, the movement-image, he finishes the year by emphasizing the importance of the post-World War II shift toward the domination of the time-image in cinema.

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

Deleuze outlines his goals for this new seminar: to provide a reading of Bergson’s Matter and Memory; likewise, to consider Kant’s Critique of Judgment; and to link these to a reflection on cinema and thought, without the seminar being on cinema, but rather entirely on philosophy. The generative question for this session (and in some ways, for the seminar) is, how are these three distinct topics unified? Bergson, Deleuze argues, leads us to a confrontation of cinema and thought. As for Kant, Deleuze speculates on whether, in proposing the Sublime in the Critique of Judgment, Kant isn’t proposing a new relation between image and thought that might be considered pre-cinematographic. Deleuze then begins (and similarly in chapter 1 of The Image-Movement) with a presentation of two theses by Bergson from Matter and Memory, starting with a detailed consideration of movement and its constitutive elements, notably, instants, immobile sections. Deleuze maintains that Bergson’s encounter with cinema occurs in understanding cinema as operating within the aggregate of immobile sections and abstract time, and therefore letting real movement escape in its relation to concrete durations. Examining the basic elements of cinema, Deleuze argues that rather than understanding cinematographic perception as movement being added to the image, Bergson helps us understand cinema as the creation of a movement-image, a synthesis of movement, but one that is an immediate perceptual synthesis, which captures as one the image and the movement. Hence, the invention of the movement-image is the act of creating cinema. As for the second thesis, i.e., cinema’s reconstitution as privileged instants and indeed defining the development in cinema as the emergence of equidistant any-instants-whatever and of intervals occurring between such instants, Deleuze shows how Bergson moved his philosophical thought toward what he judged to be contemporary science. After considering Bergson’s examples (from Kepler, Galileo, and Descartes) regarding movement, Deleuze indicates the shift from a dialectic of forms to an analysis of movement, with cinema’s birth emerging as the succession snapshots assured through the equidistance of images enabled by the perforation. After exploring the technological aspect of this development, Deleuze considers the philosophical aspect, judging Bergson as one of the first to develop a metaphysics which corresponds to current science. Deleuze links this to the seminar’s theme by asking if, in this regard, there is a properly cinematographic thought, i.e., a thought of creation which we witness while watching cinema. Having established the second thesis, Deleuze prepares to devote the second session to considering the third regarding how movement expresses duration, i.e., the extensive movement as section of a duration.

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Cinema: The Movement-Image

Lecture 1, 10 November 1981 (Cinema Course 01)

Transcription: La voix de Deleuze, Fanny Douarche (Part 1, 1:00:15) and Lise Renaux (Part 2, 1:01:44); transcription augmented, Charles J. Stivale ; translation by Charles J. Stivale

Part 1

What I would like to do this year, so that you understand, especially so that you know whether it suits you to come, to come back, here’s how it is. In a way, I would like to do three things. I would like to do three different things, even apparently very different, and I would like each of these things to stand on its own terms, for itself:

The first thing, I would like to offer you a reading of a book by Bergson, namely Matter and Memory. Why this book by Bergson? Because I think it’s a very extraordinary book, not only in itself but in the evolution of Bergson’s thought. Matter and Memory is Bergson’s second great book, after Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness; the third great book is Creative Evolution. Now, in the evolution of Bergsonian thought, it looks like — and for those who have already read or learned a little about these books by Bergson, perhaps you’ve already had this impression — it looks like Matter and Memory does not at all correspond to part of a kind of progressive linkage, but forms a very bizarre, a very bizarre detour, like an extreme point, one so extreme that perhaps Bergson reaches something there that, for reasons that we would have to determine, he will give up exploiting, which he will give up pursuing, but which marks an extraordinary apex in his thought, and in thought altogether. That’s one point, there we are. Matter and Memory, I’d like to tell you about this book.

The second point, this year, I also want to tell you about another very great book, much older, namely Kant’s Critique of Judgment. And Kant’s Critique of Judgment is a book in which Kant says what he thinks, what he thinks he should say, about Beauty and other things beyond Beauty or linked to Beauty. And this time, about this book, I would say also that it’s an apex not only for thought in general, but for Kantian thought because — not quite in the same way as Matter and Memory which represents a kind of rupture in an evolution — this time, it’s almost when we’re not expecting it anymore. The Critique of Judgment is one of the few books written by an old man, at a time when he’d almost completed all of his work. In a way, we didn’t expect much from Kant, very old, so old… And there it was, after the two critiques he had written, Critique of Pure Reason, Critique of Practical Reason, suddenly comes something that nobody had expected, the Critique of Judgment, that is going to establish what? That is going to establish a very bizarre aesthetic, probably the first great aesthetic, and which will be the greatest manifesto at the juncture of Classical aesthetics and emerging Romanticism. You see, I would say that this is also a primary book, fine, but for other reasons and in a configuration different from Matter and Memory. All of that doesn’t seem to fit together well.

And then, a third point, I would also like to do something concerning, I could say, the image and thought, or more precisely concerning cinema and thought. [Pause] But this is my question: in what way isn’t this three subjects? However, if I insist, in a way for this whole year, I’d like, and this is important for me, in order to make things easier for us, I’d like to create some sort of division. I will announce, for example, that a particular session is on the image in Bergson, another session is on an aspect of cinema, etc. I will multiply divisions, there, as quantitative: I, II … so that you know, so that you can more easily follow where we are going. For understand me, what I would like is finally that each of my three themes stands by itself, and yet that all of these intertwine absolutely, that this really creates a unity, this unity being finally: cinema and thought. And why would that create a unity? That’s my question. Why would three things so different – Bergson’s Matter and Memory, Kant’s Critique of Judgment, and a reflection on thought and cinema — why would they be unified?

Where Bergson is concerned, I’ll answer immediately that, in fact, it’s quite simple; the situation is quite simple. Why? I’ll choose a few important dates: Matter and Memory, 1896; Bergson’s next book, Creative Evolution, 1907. To my knowledge, Creative Evolution is the first philosophy book to take cinema into account explicitly and considerably, to the point that the fourth chapter of Creative Evolution in 1907 is entitled: “The cinematic mechanism of thought and the mechanistic illusion”. In 1907, this consideration of the cinema was still very early. Fine. Matter and Memory is from 1896, the date, the fetishistic date in the history of cinema, namely the Lumières’s projection, the Lumières’s projection in Paris in December 1895. I can say quite generally that Bergson cannot at the time of Matter and Memory take explicit account of cinema even if he knows of its existence. In 1907, he can do so, and he takes advantage of it. But strangely — and that will already pose a problem for us — strangely, if you read Creative Evolution and Matter and Memory, what do you tell yourself? You tell yourself that in Creative Evolution, he explicitly accounts for the existence of cinema, but according to him, in order to denounce an illusion that cinema promotes, not inventing it but, according to Bergson, one that’s hitherto known to which cinema gives an extension.

So — and the title of the chapter, “The cinematic mechanism and the mechanistic illusion” – it’s a question of denouncing an illusion or it seems to be, one would think that it’s a question of denouncing an illusion. My question is, if on the contrary, in the 1896 Matter and Memory, Bergson in a certain way was not much more in advance, and completely engaged there not with something that cinema invented, but something that he invented in the field of philosophy, something that cinema was inventing in another domain. This would perhaps be a way of explaining the unusual character of Matter and Memory. But Bergson therefore leads us to a sort of confrontation of cinema and thought, or situates itself within this confrontation, no problem.

For Kant, for Kant, it’s clearly less obvious, if only by the dates, so as a result, what interests me in the Critique of Judgment is this. In Matter and Memory, I can say, because I am obviously asking you one thing, that is, those taking the course this year are to read two books. You’re to read yourself Matter and Memory, and in fact, for next week, I’d like you to have read the first chapter of Matter and Memory. Ah, you have to, you have to, you have to, otherwise … otherwise you mustn’t come, that’s it. And then afterwards, the Critique of Judgment.

Now, if you read the Critique of Judgment, or when you read it, you will see this: that the entire beginning is about Beauty, and that’s very beautiful, but it is a kind of Classical aesthetics. It’s a kind of final word on a Classical aesthetic that involves asking oneself what beautiful forms are. When do I say that a form is beautiful? And, to ask oneself when to say that a form is beautiful is precisely the aesthetic problem of the great Classical period, but that the whole continuation of Kant’s aesthetics consists in telling us: yes, so be it, but below Beauty, above Beauty, beyond Beauty, there are certain things that go beyond the beauty of the form. And these things which go beyond beauty of the form will successively receive the name of: Sublime, the Sublime; then, the interest of the beautiful, while the beautiful by itself is disinterested, the interest of the beautiful; and finally, genius as a faculty of aesthetic ideas, in contrast to aesthetic images. All this underside of Beauty, this beyond of Beauty, is like the proclamation of Romanticism.

For me, my question is if, precisely at this level, there isn’t something, there isn’t a new relation proposed by Kant between image and thought, well, a relation which, in this case, should be called “pre-cinematographic”, but which, in another way, cinema could confirm. [Pause]

So, what I want from you, from those who will continue to attend, is to read these two books, again, starting with Matter and Memory, if you don’t mind.

A woman student: [Inaudible comment, but clearly, she mentions that the edition of Matter and Memory is out of print]

Deleuze: But this a disaster, this is a real disaster … [Pause; Indistinct comments] Well, you’ll have to go read it in the library. Oh, it may be reissued in any case … It’s not a question… This is outrageous, really, it’s outrageous … [Pause] Well, listen, you won’t read it, no, I’ll recount it to you, ok? [Laughter]. So, hurry up, in any case, to get yourself the Critique of Judgment because it will be out of print too then. The Critique of Judgment is published by Vrin. There is a recent translation; find the recent translation by [Alexis] Philonenko. Fine.

Finally, let me add because I dread greatly, I greatly dread quite legitimately, I am making clear that, in any case, right, I wouldn’t even pretend to offer you a course on cinema. So, this is a philosophy course from start to finish. There we are, there we are, there we are. So, let’s begin.

I am saying that this is how I’m starting, and already this gives us quite a lot. You understand, this year, I’d really like to pursue a kind of path with this particular focus: thought, cinema, all that, but … so as I said, I’d like to number precisely, so I am therefore starting with a really big point 1, which will keep us busy for some time, namely: Bergson’s theses on movement, Bergson’s theses on movement, Bergson’s theses on movement. This is my big point 1; I’ll let you know when I’m done. And I am saying, imagine a philosopher, it’s never that simple, huh, neither as difficult, nor as simple, nor as complicated, nor as simple as they say because a philosophical idea, it seems to me, is always an idea with levels and landings. It’s like an idea that has its projections. I mean, it has several levels of expression, of manifestation. It has a thickness. A philosophical idea, a philosophical concept, always has a thickness, a volume. You can locate them at a particular level, and then at another level, and at another level, without this causing any contradiction. But these are quite different levels.

As a result, when you lay out a doctrine, you can always make a simple presentation of the doctrine or the idea, a presentation — it’s a bit like with tomographies — a presentation in thickness, at a particular distance, all that. There was even a philosopher who saw this very, very well; it was Leibniz who presented his ideas according to the supposed intelligence of his correspondents. So, he had a whole system; this was his system: version 1, when he thought it was someone who was not well informed; then he had a system version 2, a system version 3, all that. And it was quite synchronized, it was a wonder. What I mean is that for Bergson, there are also some extremely simple pages, and then you have presentations of the same idea on a much more complex level, then on yet another level. I would say that, in some ways, regarding movement, there are three Bergsons, and that there is one that we all know, even when we have not seen it. There is one who has become so much like Bergson, the standard Bergson, really. And so, I am starting out by assuming there are three of them regarding this problem of movement, three great theses by Bergson, increasingly subtle, but simultaneous, completely simultaneous.

I am starting with the first one, or rather, by recalling the first one since you are familiar with it. The first one is very simple. Bergson has an idea that simultaneously assigns the approach of philosophy, namely: the world in which we live is a world of mixtures. It’s a world of mixtures; things are always mixed. Everything is mixed. In experience, there are only — how would we say this? — there are only mixtures. There are mixtures of this and that. These mixtures are what is given to you.

So, what is philosophy’s task? That’s quite simple: it’s to analyze, to analyze. But what does “to analyze” mean for Bergson? He completely transforms what people call “analysis”, because to analyze is to seek the pure. A mixture being given, to analyze the mixture means identifying what? The pure elements? No. Bergson will say very quickly: not at all; what is pure is never elements. The parts of a mixture are no less mixed than the mixture itself. There is no pure element. It’s tendencies that are pure. The only thing that can be pure is a tendency running through the thing. To analyze the thing is therefore to identify pure tendencies. It’s to identify the pure tendencies between which the thing is divided, to identify the pure tendencies which permeate it, to identify the pure tendencies which invest it. Fine. [Pause] So, this very special analysis that consists in identifying in a mixture the pure tendencies which are supposed to be invested together is what Bergson will call intuition, discovering the articulations of the thing. Fine.

Can I say that the thing is divided into several pure tendencies? No, no. Already at this level, you must feel [that] there is never only one pure thing. What I must do when I analyze something is to divide the thing into a pure tendency which pulls it forward, which pulls the thing forward, and what? Another pure tendency? You could say something like that, but, in fact, it never happens that way. A thing is broken down into a pure tendency which carries it forward and an impurity which compromises it, an impurity which stops it, or into several, right? It’s not necessarily two. But creating a good analysis is to discover a pure tendency and an impurity which intersect with one another. Fine. This is getting more interesting; it’s in this sense that intuition is a true analysis, an analysis of mixtures.

And what does Bergson tell us? This is very curious, but if only in the world of perception, it’s always like this, because what is given to us is always mixtures of space and time, and that’s what is catastrophic for movement, for understanding movement. Why? Because we always have a tendency — and this is where the best-known Bergson emerges — we always tend to confuse movement with traversed space, and we try to reconstruct movement with traversed space. And as soon as we embark on such an operation, reconstructing movement according to a traversed space, we no longer understand anything about movement. See, as an idea, this is quite simple.

Why is movement irreducible to traversed space? It is well known [that] movement is irreducible to traversed space since, in itself, this is the act of traversing. In other words, when you reconstitute movement with traversed space, you have already considered movement as past, that is, as already completed. But movement is the act of traversing; it is traversing in action, that is, movement is what is occurring. Precisely, when it is already completed, what remains is only traversed space. But there is no longer any movement, in other words, [this is] the irreducibility of movement to the space traversed. Why? As Bergson says, at the level of this first huge thesis, he says: it is obvious, traversed space is basically divisible, it’s essentially divisible. On the other hand, movement as the act of traversing a space is itself indivisible. It’s not space, it’s duration, and this is an indivisible duration.

At this level, where are we? At the simplest point, the categorical opposition between divisible space and indivisible movement-duration. And in fact, if you substitute for the indivisible movement-duration, if you substitute for indivisible movement, that is, which traverses a space all at once, if you substitute traversed space for this, which is divisible, you will no longer understand anything, namely: movement, literally, will no longer be possible. This is why Bergson constantly reminds us of Zeno’s famous paradoxes at the origin of philosophy, when Zeno shows how difficult it is to think of movement. Yes, it is difficult to think of movement; it’s even impossible to think of movement if you translate it in terms of traversed space. Achilles will never catch up with the turtle, as old, ancient Zeno told us, or, furthermore, the arrow will never hit its target. The arrow will never hit the target; these are Zeno’s famous paradoxes, right, since you can specify half of the arc, from the arrow’s starting point to the target, half the arc; when the arrow is at this halfway point, there is still one half left; you can divide half into half when the arrow is at this point, there is still half left, etc., etc. Half and half, you will always have an infinitely small space, however small a space it may be, between the arrow and the target. The arrow has no reason to hit the target. Yes, says Bergson, Zeno is obviously right, the arrow will never hit the target if movement is confused with traversed space since traversed space is infinitely divisible. So, there will always be a space, however small it may be, between the arrow and the target. Likewise, Zeno will not catch the turtle. There we are. So, at this first level, I’m just saying, you see what Bergson does: in fact, he opposes indivisible movement-duration to the basically, essentially, divisible traversed space. [Pause]

If that’s all there was, this would certainly be very interesting, but finally, we sense that this can only be a starting point. And in fact, if we stay with Bergson’s first thesis, I immediately see that this first thesis itself has – it’s not another thesis — it has a possible presentation that’s already much more… much more curious. However, at first glance, this does not seem to have changed much. This time, Bergson no longer tells us my first proposition was: we do not reconstruct movement with traversed space.

The second presentation of this first thesis, of this same thesis, is a bit different. It’s this: we do not reconstruct movement with a succession of positions in space, or of instants, of moments in time. We do not reconstruct movement with a succession of positions in space or with a succession of instants or moments in time. In what way is this thesis much more advanced this way? What does this add to the previous formulation? It is clear that the two formulations are completely linked. What do they have in common, position in space or instant in time? Well, in and of themselves, these are immobile sections. These are immobile sections seized, operated along a pathway. So, Bergson no longer tells us exactly: you will not reconstitute movement with traversed space; rather: you will not reconstitute movement even by multiplying immobile sections seized or operated along the movement. [Pause]

Why is that more interesting to me? Why does this seem to me already another presentation of an idea? Earlier, you remember, it was simply a matter of establishing a difference in nature between divisible space and indivisible movement-duration. On this second level, it is something else. What does this concern on the second level? It’s … it’s very odd, because when I pretend to reconstitute movement with a succession of moments, of immobile sections, in fact I am causing two things to intervene: on one hand, immobile sections, on the other hand, the succession of these sections, of these positions. In other words, on that side, on the left side — you sense that the left side of the analysis is always the impure side; it is the impurity there that impedes the pure tendency — well, on this left side, what do I have? I no longer have a single term: space is divisible; I have two terms: the immobile sections, that is, the positions or instants, and the succession that I impose on them, the form of succession that I make them undergo. What is this form of succession? It is the idea of an abstract, homogeneous time, [Pause] equalizable, uniform, the idea of abstract, uniform, equalizable time. [Pause] This abstract time will be the same for all assumed movements. So, for each movement, I would select immobile sections. All these immobile sections, I would make them follow one another according to the laws of a homogeneous abstract time, [Pause] and I would attempt to reconstitute movement in this way. [Pause]

Bergson asks us: why doesn’t that work? Why doesn’t that work, and here as well, why is there the same misinterpretation as earlier regarding movement? Movement always occurs between two positions. It always occurs within the interval. As a result, concerning movement, although you can make the immobile sections as close to each other as you want, there will always be an interval, however small it may be, and movement will always occur within the interval. This is a way of saying [that] movement always occurs behind your back. It occurs behind the thinker’s back; it occurs behind the back of things; it occurs behind people’s backs. It always occurs between two sections. As a result, although you may multiply the sections, it’s not by multiplying the sections that you will reconstitute movement. It will continue to occur between two sections, however close your sections may be.

This irreducible movement that always occurs within the interval [Pause] does not allow itself to be confronted; it does not allow itself to be measured by an abstract homogeneous time. What does this mean? It means that there are all kinds of irreducible movements. There is the horse’s pace, and man’s pace, and the turtle’s pace, and there is no point in laying out these movements on the same line of a homogeneous time. Why? These movements are irreducible to each other; that’s why Achilles moves past the turtle. If Achilles moves past the turtle, it is for a very simple reason: it is that his very own units of movement, namely an Achilles leap, has no common measure — this is not because there is a common measure — [it] has no measure common with the turtle’s little pace. And sometimes you may not know who will win. A lion pursues a horse. There is no abstract time, there is no abstract space, right, which indeed allows you to say, first, there is something unpredictable. Is the lion going to take the horse or not? If the lion takes the horse, it is with the lion’s leaps. And if the horse escapes, it is with the horse’s gallops. These are qualitatively different movements. These are two different durations. One can interrupt the other; one can overcome the other. They are not composed of common units. And it is with a lion’s leap that the lion will jump on the horse, and not with an abstract quantity that can be displaced into a homogeneous time.

What is Bergson telling us? He tells us: all concrete movements, of course, have their articulation; each movement is articulated in one way or another. In other words, but of course, movements are divisible; of course, there is a divisibility of the movement. For example, the Achilles race is divided into… into … — what’s that called? the unit of human steps … — in strides, Achilles’s course is divided into strides. Very good. The horse’s gallop gets divided. Obviously, it gets divided, the famous formula: 1.3.2 … 1.3.2 … 1 … All movements are divisible. Notice that this is already becoming much more complex. But they are not divisible according to an abstract homogeneous unity. [Pause]

In other words, each movement has its own divisions, its own subdivisions, so that one movement is irreducible to another movement. One step by Achilles is absolutely irreducible to one turtle’s step. As a result, when I make immobile sections within movements, this is always to bring them back to a homogeneity of uniform abstract time, thanks to which precisely I standardize all the movements, and I no longer understand anything about the movement itself. At this point, Achilles cannot catch up with the turtle.

Student: Is the encounter possible?

Deleuze: The encounter, oh yes, anything is possible. In order for the encounter, for Achilles and the turtle to meet, it is necessary that Achilles’s duration or movement find in his articulations to it, and that the turtle finds in the articulations of its movement to it, something that causes the encounter to occur within one and the other of both movements.

In other words, what is he telling us there? Notice that earlier, this was the first presentation of his thesis. It consisted in saying: distinction of nature, opposition, if you will, between traversed space and movement as act of traversing. Now, the second presentation already seems to me much more interesting and intriguing. He distinguishes, he opposes two sets: first set, on the left, immobile sections plus the idea of succession as abstract time, immobile sections plus the idea of succession as abstract time, and on the other side, on the right, movement, movement qualified as a particular movement or another plus concrete duration which is expressed in this movement. [Pause]

Okay, so maybe you understand why suddenly, the encounter, the confrontation with cinema takes place, and why, in Creative Evolution, Bergson collides with this birth of cinema. For cinema arrives with its ambition, founded or unfounded, not only of bringing a new perception, but a new understanding, a new revelation, a new manifestation of movement. And, at first glance … at first glance, Bergson has a very hostile reaction. His reaction consists in saying: well yes, well you see, cinema only pushes to the extreme the illusion of the false reconstitution of movement. In fact, what does cinema proceed with? It obviously belongs to the bad half, apparently; it proceeds by making instantaneous sections into movement, instantaneous sections, and subjecting them to a form of succession of a uniform and abstract time. He says: this is sketchy.

Is this sketchy? Didn’t he … he’s not figuring out about cinema in 1907 something that most people, even starting with some of his more advanced followers than he was, that nonetheless for cinema, for example, Elie Faure, I think, had not yet understood… concerning … — this is complicated — that, because the conditions of cinema at Bergson’s era, you know them well; what were they? Speaking quite generally, quite generally, it’s this: immobile viewing point (prise de vue), identity of the apparatus for shooting with projection, and finally, something that seems to justify Bergson completely and which has not ceased, a great principle without which cinema would never have existed, finally a great technical principle, really, something that ensures the equidistance of images. There would be no projection if there were no equidistance of the images, there would be no cinematographic projection.

And everyone knows that one of the technically fundamental points in the invention of cinema, of the cinema machine, was to ensure the equidistance of the images, thanks to what? Thanks to the perforation of the film strip. If you don’t have equidistance, you won’t have cinema. We will see why; I am leaving this question aside but intend to try to explain it later. And Bergson is well aware of this, and of the Lumière brothers’ apparatus. And already, to ensure the equidistance of images by the perforation of the strip, this is whose discovery? It’s the discovery, just before the Lumières, it’s Edison’s discovery, meaning that Edison had some quite justified claims about the very invention of cinema. So, it was a technical act, even if we might consider it in other respects to be secondary, this equidistance of instantaneous images was a technical act which really conditions cinema.

And that seems to entirely justify Bergson. What is the formula for cinema in 1907? Succession of snapshots, the succession being ensured by the form of a uniform time, two images being equidistant, the images being equidistant, the equidistance of the images guarantees the uniformity of time. So this criticism of the cinema by Bergson, it seems very … at that time, all cinema operates within the aggregate [of] immobile sections and abstract time, and therefore lets movement escape, namely the real movement in its relation to concrete durations. [Pause] Good.

At that point, can we say that, henceforth, can we, are we able to refer to the state of cinema afterwards in order to say: ah well yes, but was Bergson the beginning of cinema? So much has happened, namely for example, can we refer to the fact that the camera has become mobile, to say: oh well no, here cinema has recovered true movement, etc.? And that would not change, what remained … that would not change… What remained [was] cinema’s basic fact, namely that movement is reproduced starting from snapshots, and that there is a succession of snapshots implying the equidistance of the corresponding images. It is difficult to see how this would not subsist since, otherwise, there would be no more cinema. There would be something else; there would be something else, but that wouldn’t be cinema.

As a result, our problem would not be, could not consist in invoking an evolution of cinema after 1907. I believe that what we must invoke is something entirely different. This is a problem that I would call the first problem relating to cinema, namely the problem of perception. Fine, cinema gives me movement to perceive. I perceive movement. What does Bergson mean when he denounces an illusion linked to cinema? What does that mean? What does he want? What is he looking for? After all, perhaps if we ask this question, we will notice that Bergson’s criticism of cinema is perhaps much more apparent than real, this very harsh criticism, namely: cinema proceeds by immobile sections, by snapshots, by immobile sections. It makes do with subjecting them to a form of abstract succession, to a form of abstract time. Fine.

I am saying, it is understood that — but, what does that mean? — it is understood that the means… cinema reproduces movement. Fine, it reproduces. Reproduced movement is precisely perceived movement in cinema. Perception of movement is a synthesis of movement. It’s the same thing, to say synthesis of movement, perception of movement, or reproduction of movement. If Bergson wants to tell us that movement in cinema is reproduced by artificial means, this is obvious. Moreover, I would say something simple: what reproduction of movement is not artificial? This is included in the very idea of reproducing. Reproducing a movement obviously implies that the movement is not reproduced by the same means by which it is produced. This is even the meaning of prefix re-. So, it is necessarily by artificial means that something, be it movement or something else, that something is reproduced.

So that movement in cinema is reproduced by [artificial] means… [Interruption of the recording] [46:00]

… does that mean that the movement that I perceive, that the reproduced movement, is itself artificial or illusory? Understand my question. The means of reproduction are artificial; does that mean, can I conclude from the artificial nature of the means of reproduction in the illusory nature of the reproduced? [Blank in the recording]

… Through the very method, what might he tell us, a Bergson ghost? He just told us: natural perception, ultimately, what we grasp in experience, our natural perception, is always a perception of mixtures. We only perceive mixtures; we only perceive the impure. Okay, fine, under natural conditions, you only perceive the impure, mixtures of space and time, mixtures of the immobile and movements, etc. We perceive mixtures. Very well, very well, we perceive mixtures. But precisely, cinematographic perception it’s well known — we will have to come back to this, like that, but it is a basic principle that must be established immediately, that must be recalled immediately — cinematic perception is not natural perception. Not at all. [Pause] Movement is not perceived in cinema, the movement of a bird in the cinema, is not at all perceived – I am speaking in terms of perception, huh — is not at all perceived as the movement of a bird in the natural conditions of perception. It’s not the same perception. Cinema has invented a perception. This perception, once again, is definable; it will have to be defined. How does it proceed through difference with perception in natural conditions? Fine.

Therefore, what prevents me from saying that, precisely, [Pause] cinema offers us or pretends to offer us a perception that the natural conditions of the exercise of perception could not give us, namely, the perception of pure movement, as opposed to the perception of mixtures? As a result, if the conditions for reproducing movement in cinema are artificial conditions, that does not at all mean that it is artificial. This means that cinema invents the artificial conditions which will make possible a perception of pure movement, understanding that a perception of pure movement is what natural conditions cannot offer because they condemn our natural perception to its mixed ideas. As a result, this comes down to the whole artifice of cinema being used for this perception and for the erection of this perception of pure movement, or of a movement which tends towards the pure, towards its pure state.

Why does … And in fact, what makes us say that? It is because if we hold to the Bergsonian description of the conditions for the reproduction of movement in cinema, we get the impression that there are, on the one hand, the immobile sections and, on the other hand, the movement which brings about these sections, the abstract uniform movement, time, this abstract, homogeneous time. And this is true from a point of view of projection, but it’s not true from a point of view of perception.

What is the fact of cinematographic perception? It’s that movement is not added to the image. Movement does not get added to the image. There is no image, and then movement. In the artificial conditions that Bergson has well determined, what is presented by cinema is not an image to which movement would be added. It is a movement-image — with a little hyphen, with a little dash — it is a movement-image. Of course, this is reproduced movement, that is, reproduced movement, I tried to say what that meant. That means: perception of movement, or synthesis of movement. It’s a synthesis of movement. Only here we are, when I say movement is not added to the image, I mean the synthesis is not an intellectual synthesis. It is an immediate perceptual synthesis, which captures the image as a movement, which captures in one the image and the movement, that is, I perceive a movement-image. To have invented the movement-image is the act of creating cinema.

Yes, Bergson is right because this involves artificial conditions. Why? We shall see. We have not at all yet said why this implied such artificial conditions, namely it implies this whole system of instantaneous immobile sections, made within movement, and their subsequent projection, in fact, an abstract time. But that does not go beyond artificial conditions. But what is it that these artificial conditions condition? They do not condition an illusion or an artifice. Once again, I cannot conclude from the artificiality of the condition about the artificiality or the illusion of the conditioned. What these artificial conditions of cinema make possible is a pure perception of movement that natural perception, of which natural perception was absolutely incapable. We will express this pure perception of movement in the movement-image concept.

And what a wonder, is it against Bergson that I am fighting in all this? No, not at all, not at all, because Matter and Memory had already said this. Because Matter and Memory — and that was the subject of the first chapter of Matter and Memory — where Bergson — so he couldn’t at that time refer to cinema — told us roughly this in the first chapter: in one way or another, it is necessary to reach the following intuition, the identity of the image, of matter and of movement. He says: and for this, to reach the identity of image, matter and movement, he said, it is necessary — this is very odd — it is necessary to get rid of all knowledge; we must try to find an attitude, which was not the naive attitude; he said, it’s not a naive attitude, nor is it a learned attitude. He did not know very well how to qualify — you will see by reading the text that will be printed — he did not know very well how to qualify this very special attitude, in which one might to be able to grasp this bizarre identity of image, movement and matter.

And there, we’ve moved forward a bit. You see, this would be the first problem that cinema would really pose for us, namely: what is this perception of movement that we could ultimately qualify as pure, as opposed to non-pure perception, to mixed perception of movement under natural conditions? Fine.

Here we have Bergson’s first thesis; if I summarize this first thesis on movement, it consists in telling us: be careful not to confuse movement either with the traversed space, or with a succession of immobile sections made within it, because movement is something else entirely. It has its natural articulations, but its natural articulations are what make one movement not another movement, and the movements cannot be reduced to any common measure. So, here is this true movement or this pure movement, or these pure movements. Our question was: is that what the perception of cinema gives us? Fine.

Bergson’s second thesis. This second thesis, then, it will make, it will cause us to make, I hope, some considerable progress. Listen to me. You are not tired yet, eh? Because here you have to make… I would like you to pay very close attention because it seems to me that this is a very big idea from Bergson.

He moves back a little bit, right, and he tells us: well, okay, there are all these attempts, because thinking humanity, thought, has never stopped doing that, wanting to reconstitute movement with what’s immobile, with positions, with instants, with moments, etc. Only, he says: there, in the history of thought, there have been two very different ways. They always have in common — this bad thing, notice, there this impure thing — pretending to reconstitute movement from what is not movement, that is, from positions in space, moments in time, finally from immobile sections. That has always been the case. And Bergson — that’s part of philosophers’ pride — but Bergson can rightly believe that he is the first to attempt the constitution of a thought of pure movement. Fine.

Only, he says: this thing that we tried, reconstituting movement with positions, with sections, with moments, in the history of thought, this has been undertaken in two very different ways. Hence immediately, our question before he begins: and these two ways, are they also bad? Or is there one less bad than the other? Above all, what are these two ways? There, I believe that Bergson writes texts of clarity, of rigor, which are immense. So, you have to be patient here; listen to me well. He says: well, yes, for example, there is a very big difference between ancient science and modern science. And there is also a very big difference between ancient philosophy and modern philosophy. And what is it? Generally, we are told: ah, yes, modern science is much more quantitative, while ancient science was still qualitative science. Bergson says: this not wrong, but in the end, it’s not about that; that doesn’t work; it’s not good, that idea hasn’t been fully developed. And he feels strong enough to assign a kind of very interesting difference. He says: well here, precisely, regarding movement, he states how the ancient physicists, for example, the Greeks, but again in the Middle Ages — all that, it will unfold in the Middle Ages, the birth of modern science — and in Antiquity, how did physicists or philosophers or anyone treat movement? Do you remember? For you to follow well, you must remember the basic givens.

In any event, both of them recompose, or pretend to reconstitute movement with instants or positions. Only here, the Ancients claim to reconstitute movement with privileged instants, with privileged instants, with privileged moments, with privileged positions. Since there is a convenient Greek word — you will see why I need the Greek word to indicate these privileged instants — the Greeks use the word, precisely, “position”, “thesis”, “thesis”, “Thesis“, position, positioning, thesis. It’s strong time, the thesis, it’s strong time as opposed to weak time. Good. [Pause] In other words, with what are they claiming to reconstitute movement together? There is the French word which corresponds exactly to the Greek word thesis, it is the word “pose”. [Interruption of the recording] [1:00:18] [Fin du CD I, Gilles Deleuze Cinéma]

Part 2

… We are going to reconstitute movement with poses, p-o-s-e, not p-a-u-s-e — that would also be fine — but with poses. What does that mean? You will see in… precisely in chapter four of Creative Evolution, that you must read then, because this one isn’t out of print. He says it very well: why yes, take Aristotle’s physics, Aristotle’s physics; when it comes to analyzing movement, what does he tell us? He essentially retains two, two theses, two poses, two privileged moments: the moment when the movement stops, because the body has reached its so-called “natural” place, and on the other hand, the vertex of movement, for example, in a curve the point is the extremum.

Here we have a very simple case: we retain positions, poses; we proceed with poses, we retain privileged positions within a phenomenon, you see, and we will refer the phenomenon to be studied to its privileged positions, its privileged instants. For example, this is the same thing in art; all Greek art will be established precisely as a function of privileged moments. Greek tragedy is just like the extremum of a movement; it is what the Greeks call as much for the physical movement as for the movement of the soul in the tragedy, it is what they call the acme, the point at which there is no higher; before that goes up to this point and after that goes down. This extreme point… this extreme point, it will be precisely a privileged moment.

Fine, so what does that mean exactly? What is a pose? I would say a pose is a form, a pose, a position, is a form, and in fact, movement is related to forms — not to a form — to forms. What does that mean, movement is related to forms? It’s not that the form itself is in motion. On the contrary, a form is not in movement; it can tend towards movement, it can be adapted to movement, it can prepare movement, but a form in itself is the opposite of movement. What does that mean? This means that a form is or is not realized, is realized in a kind of matter. The operation by which a form is realized in a matter is what is called, what the Greeks call, an information. A form realizes a matter, for example, a sculptor realizes a form in matter, Aristotle says.

Okay, what is that is moving? What is in motion? It’s matter; what moves is matter. What does it mean to move then? It’s going from one form to another. It is not the form that changes; it’s the matter that goes from one form to another. That’s a constant idea for Plato; it’s not the small that gets big; it’s not cold that gets hot. But when water heats up, a fluid matter, water, passes from one form to another, from the form of cold to the form of hot; it is not cold which becomes hot. The forms in themselves are immobile or else they have movements of pure thought, but finite movement is that of a matter which passes from one form to another. A horse gallops; in fact, here you have two forms; you can distinguish one form of a horse and the sketch artist another, the form of the horse at the maximum of its contraction and the form of the horse of its muscular contraction, and the form of the horse at the maximum of its muscular development. And you will say that the gallop is the operation by which the “horse matter”, the horse’s body with its mobility, does not cease to pass from form A to form B and from form B to form A.

Maybe you understand what we are saying then? I am saying, there is, according to Bergson — it seems that he barely changes the terms — there is a first way to reproduce movement, and this first way, what is it? You can reproduce movement as a function of instants of privileged moments, and what does that mean? At that point, you reproduce movement as a function of a sequence of forms or an order of poses: sequence of the contracted form of the horse and the dilated form of the horse, and while this is the matter, the material body of the horse which passes from one form to another. In other words, it is not the form itself that moves; it is the matter that moves by passing from form A to form B. Forms are simply more or less captured close to their moment of actualization in a matter.

So, when I was saying a form is more or less “ready” for mobility, that means, you grasp it either for itself or at its point of actualization in a matter. And all Greek art will play — while philosophy will be responsible for thinking about forms in themselves — Greek art will be responsible for causing forms to emerge to the point of their realization in a fleeting matter. And you see then, it seems to me, Bergson is absolutely right to say and define ancient thought by this reconstitution of movement ultimately starting from the reconstituted movement [that] will depend on what? It will depend on the sequence of forms or poses. But a sequence of what nature? It’s a sequence that will be a logical sequence, not a physical sequence. What is physical is the movement of matter that passes from one form to another. But the relations between forms is from logic, it is from the dialectic. In other words, it is a dialectic of the forms or of poses which will serve as a principle for the reconstitution of movement, that is, the synthesis of the movement. It is a dialectic of forms or poses which will serve as a principle for the synthesis of movement, that is, for its reproduction. For example, dance: in dance, the flowing body of the dancer, man or woman, passes from one pose to another and, no doubt, the forms of dance are grasped at the maximum of the point of their actualization. This does not prevent the dance movement from being generated through this sequence of poses.

Understand the conclusion that I already anticipate. At this level, and if we had stayed there, there would be no question that there is anything that resembles cinema. On the other hand, it would be a question of what? Everything else: magic lantern, shadow puppets, whatever you want. I would like to suggest to you, in fact, one cannot make an absurd technological lineage as in … One cannot make an absurd technological lineage which would begin, or which would seek a kind of pre-cinema in shadow puppets or magic lanterns. That has absolutely no place; there is a bifurcation. Cinema implies a bifurcation of the technological lineage. In other words, I would say: as long as you reconstitute — you can very well reconstitute movement, you reproduce movement — but as long as you reproduce movement starting from a sequence of forms or poses, you have nothing that resembles cinema. Once again, you have shadow puppets; you have moving images; you have everything you want, but it’s not cinema. You have dance, you have everything, but that has nothing to do with cinema.

And what has modern science done? What is its purpose according to Bergson? His stroke of genius is at the same time his very disturbing feat — if you followed me, you will understand right away — his stroke of genius is this: in modern science, here’s what modern science has done: it reconstituted movement, but not at all in the manner of the Ancients. In the same attempt to reproduce movement, to reconstitute movement, how did modern science proceed? At this point, it reconstituted movement from an instant or any-moment-whatever (un moment quelconque). And this is the startling difference, it is the unfathomable difference between the two sciences. Modern science was born from the moment it said: movement must be defined as a function of an unspecified instant. In other words, there is no privilege of one instant over another. I could also say very quickly, from an aesthetic point of view, that this was the end of tragedy, and it was the birth of what? Of the novel, for example in literature, the novel is good.

And what does that mean, the movement referred to any-instant-whatever instead of being referred to privileged instants, and henceforth instead of being re-engendered, reproduced starting from real privileged instants? In this, it will be reproduced starting from any-instant-whatever. What does any-instant-whatever mean? Understand, this is a very concrete concept. It means such an instant that you cannot situate it by granting it the slightest privilege over the following instant. In other words, any-instant-whatever means equidistant instants. This doesn’t mean every instant; it means any instant at all provided that the instants are equidistant. What modern science invents is the equidistance of instants. This is what will make modern science possible, and in Creative Evolution, in this chapter four to which I’m referring you, Bergson gives three examples, so to fully understand his idea of the any instant whatever, Galileo, no, Kepler first, Kepler and astronomy, Galileo and the fall of bodies, Descartes and geometry.

He says, what is there in common? How does this really mark the dawn, the beginning of modern science? It’s because, in the three cases, as much in Kepler’s astronomical orbit, as in the fall of bodies according to Galileo, as in the figure according to the geometric figure according to Descartes, what is there that is surprisingly new? You see these Greek mathematicians, in a Greek surveyor, for example, a figure is defined by its form. What does that mean, the form of a figure? That means precisely its theses, its positions, its privileged points. A curve will be defined; Greek mathematicians are extremely learned; they advance the analysis of curves very far; they define it as a function of privileged points.

The great idea of Descartes’s geometry is, for example, that a figure refers to a path, a path that must be determinable at any instant, at any instant of the trajectory. That is, the idea of any-instant-whatever appears fully. When you relate the figure no longer to the form, but to the instant, such as, that is, [no longer] to a privileged moment, but to any-instant-whatever, what do you have? You no longer have a figure, you have an equation, and one of the possible ways of defining an equation is precisely the determination of a figure according to the any-instant-whatever concerning the trajectory that describes this figure.

So, I hope you will read these very beautiful pages by Bergson. And here we see that this is really an entirely different way of thinking; even grasp that, at the extreme, these two systems are so completely different systems that they cannot understand each other. In one case, you pretend to reconstitute movement starting from privileged instants which refer to forms outside of movement, to forms which are actualized in a matter. In the other case, you claim to reconstitute movement starting from immanent elements of movement.

I would say, starting from what, what is opposed to the pose? You will reconstitute movement no longer with poses, but with snapshots. [Pause] It’s the opposition, it’s the absolute opposition of cinema and dance. Of course, you can always film a dance, that’s not what matters. When Elie Faure begins his very beautiful texts on cinema with a sort of cinema-dance analogy, there is something that doesn’t work. These are two absolutely, absolutely opposite reconstitutions of movement. And why, what does that mean? Let’s try to express it, then, technically, technologically. I would say, in fact, it’s really the … when from a desire for a universal history, we are told, we are told a story that would go from the magic lantern all the way to the cinema, because in the end, it’s is not that, it’s not that! I am even choosing examples which are in all the histories of cinema, some very late examples. In the 19th century, you have these two very well-known devices: the fantascope, the disc fantascope, and then you have the praxinoscope. [1:18:05]

– [Deleuze speaks to a student in a very low voice] Oh, stop laughing all the time, it’s annoying for me because I can’t manage to think anymore; you are there all the time, you’re annoying me, or else place yourself off to the side, I don’t know, or just don’t come, I mean, it’s annoying; I can’t focus my ideas anymore – [1:18:20]

Or the praxinoscope by … — what was his name? We see it everywhere … – by [Charles-Emile] Reynaud, what’s going on? You recall the principle; it is precisely on a circle there; drawings are made, and then with the rotating circle, they’ll be projected, right, onto a mirror, or else with Reynaud, there will be a central prism which does away with the mirror, fine, all these details are very well known. How does this have nothing to do with cinema? It’s all that’s been drawn. Whether they’ve drawn this or photographed it, it doesn’t change anything. Whether it is real — the shadow puppet method – these are part of the real body; whether it’s an image — a drawing or as in dance, of the real, the body; whether it is… yes, if I take it in order, whether it is of the body, whether it is shadow, whether it is an image, a drawing, or whether it is a photo, that does not change anything. You will have synthesized the movement starting from a sequence of forms. What I was calling… You will have created a synthesis of movement starting from an order of poses; you will have perfectly animated images, that, yes … yes … yes, [it has] nothing to do directly or indirectly with the cinema; that’s not cinema’s gimmick.

When does it start? When does cinema start? I would say something simple: it starts exclusively — not that it already exists — but it is made possible, when is it possible? When is it, how is cinema possible? … Cinema is possible from the moment there is an analysis of movement in the literal sense of the word, when there is an analysis of movement, such that a possible synthesis of movement depends on this analysis. What will define cinema is indeed a synthesis of movement, that is, a perception of movement — giving movement to be perceived — but there is no cinema, and nothing around resembling cinema when the synthesis of movement is not available, is not conditioned by an analysis of movement. In other words, as long as the synthesis of movement is conditioned by a dialectic of forms or by an order or by a logic of poses, there is no cinema. Cinema exists when an analysis of movement conditions the synthesis of movement.

A student: [Inaudible question, possible about the eyes being a camera, judging from Deleuze’s rapid answer]

Deleuze: What, … that … no … no … no. You shouldn’t disturb me; you have to recall this question since in … at the end here, and constantly… and that one, I won’t forget it. In my first element, I greatly emphasized the difference of cinema perception with natural perception. What does it mean? [Pause] … The question, I would say there … I hastily answered “no”; I don’t know if our eye is a camera. That doesn’t make much sense, but on the other hand, I would say: even if our eye is a camera, our vision is not a cinema vision; our vision, our visual perception is not a cinematographic perception. As for the question of the relation between eye and camera, that … that seems to me much more complicated. In any case, that does not change the fact of the difference in nature between cinema perception and perception in natural conditions.

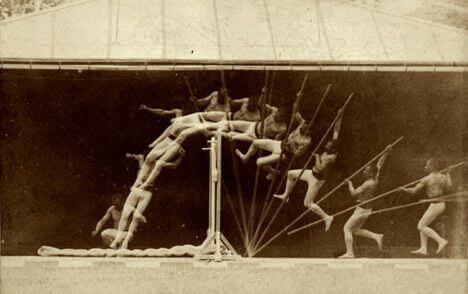

So, what was I getting at? … Yes, how does this occur historically, in fact, the formation of cinema? The analysis of cinema, no, sorry … The analysis of movement does not necessarily involve photography. Even historically, we know that one of the first persons to have advanced the analysis of movement quite far was [Étienne-Jules] Marey. [See The Image-Movement, pp. 5-7] How does he advance the analysis of movement? Quite precisely by inventing graphic devices which make it possible to relate a movement to one of these any-instants-whatever. So Marey is a modern scholar in the Bergsonian sense. Bergson had a perfect expression that summed it all up; he said, the definition of modern science is this: it is a science that has found the means to consider time as an independent variable. That’s what it is to relate movement to any-instant-whatsoever; it’s treating time as an independent variable. The Greeks never had the idea of treating time as an independent variable. Why? There are all kinds of reasons why they couldn’t treat time as an independent variable. But this kind of liberation of time grasped as an independent variable is what makes it possible to consider movement by relating it to any-instant-whatever.

And how did Marey do it? He used his graphic devices to record all kinds of movements: movement of the horse, movement of the man, movement of the bird, fine, etc. The bird was more difficult, but in the end, what did that consist of? There was no photo, at least at the start — Marey will use the photo — but at the start, what’s going on? He uses recording devices, namely the feet, the horse’s hooves, are captured in devices, some kinds of cushions with threads. It’s a very beautiful device, very beautiful, for feet, for vertical movements. The horse’s rump is itself grasped in an apparatus, the rider’s head with a small hat of all kinds, and then it’s the rider obviously who holds the recording gimmick where all the threads meet, all that, and this obtained his famous curves which you find in Marey’s books and which are very beautiful and which enabled the discovery of this admirable thing, precisely that the horse’s gallop does not occur with two poses. Contrary to what painters and artists precisely and necessarily believed, the horse’s gallop does not depend on a dialectic of forms, but simply presents a succession of snapshots, namely the horse stands on one foot, on three feet, on two feet, on one foot, on three feet, on two feet, etc., etc., at equidistant instants. This discovery is quite overwhelming; it is the substitution, I would really say, it is the substitution of the analysis of movement for the dialectic of forms or the order of poses or the logic of poses.

Well, what’s going on? Do you know the story? So, I’ll summarize it for some of you. Here you have an equestrian, someone who is really familiar with horses, who is so amazed to see that a galloping horse is standing on one foot; he says that this is not possible! He contacts a very good photographer, one that’s very, very full of mischief, and asks him, how do we verify this with photos? This is Marey’s story since Marey only had his recordings, only his curves.

Claire Parnet: This [photographer] was Muybridge, isn’t it?

Deleuze: [Eadweard] Muybridge, yes, yes, yes, yes, and the photographer is going to have this very, very good idea, of putting at equivalent distance — and it’s again the principle of equivalence which is fundamental — this camera connected to a wire, which will be tripped when the horse passes; so the camera will snap, and he will have his succession of equidistant images that will confirm Marey’s results.

So good, this must open up new horizons for us: when does cinema exist? Once again, when the dialectic of forms gives way to an analysis of movement, when the synthesis of movement is produced through an analysis of movement, through a prior analysis of movement, and no longer by a dialectic of forms or poses. What does that imply? Does it involve the photo? Yes, it involves the photo. Obviously, it involves the photo, and it involves the equidistance of the images on the tape, that is, it involves the perforation of the tape. Here we have cinema; it involves the photo, but which photo? There is a photo of pose; if photography had remained a photo of pose, cinema would never have been born, never. We would have stayed at the level of the praxinoscope; we would have stayed at the level of the disc device or the device from – what’s its name, I don’t know any more — or the Reynaud device, we would not have had a cinema. And in fact, cinema appears precisely when the analysis of movement occurs at the level of the series of snapshots and when the series of snapshots replaces the dialectic of forms or the order of poses. Suddenly perhaps, are we then able to understand in what situation — at the same time that the cinema did an amazing thing, namely there is no connection between the reproduction of the movement starting from an analysis of the movement, i.e. a succession of snapshots, no relation between that and a reproduction of movement, although there is also reproduction on the other side, a reproduction of movement starting from a dialectic of forms or an order of poses, a logic of poses?

I would say, what made cinema possible is not even the photo; it’s the snapshot starting from the moment that we were able to ensure the equidistance of the images by the perforation. So good, that’s the definition as a technique, but we can clearly see that, henceforth, cinema was in a kind of situation, at the extreme, with no way out. Its greatness created, its very novelty resulted, from the start, in people turning against it, opposing it, saying, but then why is this of interest? Where’s the interest? If it is a question of reproducing movement starting from a series of snapshots, what’s the point? Artistic interest, null aesthetic interest, null scientific interest, or else so small, so small. There we see everyone turning against it due to its originality, yes, because it’s admitted that all this is possible, that cinema reproduces movement starting from an analysis of movement, that still does not prevent that there is art — and this is a condition of art — only to the extent that movement is reproduced from an order of poses and from a dialectic of forms.

And in fact, the proof that cinema is not art, we invoked it, like Bergson, in this mechanical succession of snapshots. And from a science point of view, is this at least interesting? Obviously not! Why? Because what interests science is the analysis of movement – reproduction is a joke — and in fact, if you take Marey, it’s very clear in his work that what interests him — that’s why he did not always proceed through the photo — what interests him is the analysis of movement, that is, … [Brief interruption of the recording][1:31:40]

… A pure perception, or a synthesis of movement: the old way as a function of privileged moments, which returns us to a dialectic of forms; the modern way as a function of any-instants-whatever, which brings us back to an analysis of movement. Well then, are they equal? Are they equal? Well, there, Bergson becomes very hesitant, and it becomes this text from [Creative] Evolution, from chapter four of Creative Evolution. He says: well in the end, they are equal — his general thesis is very subtle — yes, the two ways are equal, but they could very well not have been equal. Then we would feel freer to say, well finally, they haven’t at all been equal and, in large part, perhaps thanks to Bergson. Odd.

I’m going to open a parenthesis on… Bergson, he does nothing other than his criticism of cinema, but ultimately, positively, he has a great influence — I mean, that among the first people who really thought about the cinema, there is Elie Faure who was a pupil of Bergson, and there is a man of cinema, [Jean] Epstein, who wrote very beautiful texts. And Epstein, all his texts are very, very Bergsonian; Bergson’s influence on Epstein is obvious – fine then, so he says to us: well yes, in a certain way, the two ways are equal, the ancient and the modern confront each other. Why? What is there in common between the two ways? Well, what there is in common between the two ways, you understand, is that in any case, we recompose movement with what is immobile, either with forms which transcend movement and which only realize themselves in matter, or with immobile sections (coupures) internal to movement, and this amounts to the same from a certain point of view. From a certain point of view, we always recompose movement with positions, with positions, either privileged positions, or arbitrary positions, either with poses, or with snapshots, and then so on. That is, in both ways, movement was sacrificed for the immobile, and duration was sacrificed for a uniform time.

So, to leave it there would not be good either. That is, what is it that we miss in both cases? What we miss in both cases is always the Bergsonian theme, what happens between two sections, what we miss in both cases is the interval, and movement occurs in the interval. What is it that’s missed as much in the second case as in the first? This is what happens between two instants — there is only that of importance, however – namely, not the way one moment succeeds another, but the way a movement is continued — the continuation from one instant to another — it is the continuation from one instant to another, right? It cannot be reduced to any of the instants and to any succession of instants. What we missed, therefore, was duration, the duration which is the very continuation from one moment to the next. In other words, what we missed is that the next instant is not the repetition of the previous one. If it is true that the preceding one continues into the next, the next one is not the repetition of the previous one. This phenomenon of continuation which is one with duration cannot be grasped if we summarize movement within a succession of cuts.

Furthermore, what is there in common between the ancient method and the modern method? Well, what’s in common is that for one as for the other, everything is given, and that is Bergson’s great cry when he wants to criticize both the modern and the ancient and demarcate his difference. These are thoughts in which everything is given, understanding this in a strong sense, everything is given. We might also say, the Whole is given; for those thoughts, the Whole is always given or giving, everything is given because the Whole is giveable. What does that mean: “the Whole is giveable”? Indeed, consider the ancient thought; there is this order of forms, this order of forms which is an eternal order. It is the order of Ideas, with a capital I, and time, since time arises when Ideas are embodied in a matter, what is time? Time is never only a degradation; it is a degradation of the eternal. Plato’s splendid formula: “Time, moving image of eternity”, and movement is like a degraded image of eternity, and all Greek thought makes time a kind of image of the eternal.

Hence the concept of circular time: everything is given, everything is given since the last reasons are out of time in eternal Ideas. And in modern science, the principle arises that a system can be explained at a given moment by virtue of the previous moment. It’s as if the system died and was reborn at every moment, the next instant repeats the previous instant. Here as well, in another manner in modern science, everything is given – notably, for example, in the conception of astronomy. I’m not saying modern astronomy, not current, not contemporary astronomy, but eighteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth-century astronomy — everything is given, that is, the Whole is given this time, and what is it? Not in the form of eternal, timeless Ideas. This time, it is the form of time that is given; it is movement in the form of time which is given; movement is no longer what occurs, it is only an already done, it is there, it is done. As a result, in two different ways, either because philosophy and modern science give themselves time, or because the ancients give themselves something out of time, for which time is only a degradation, in both cases: everything is given, that is, the Whole is of the order of the giveable. Simply, we will say, ha well, yes! We people do not reach the Whole; why? We do not reach the Whole. [It’s] because we have limited intelligence, we have limited understanding, etc. but the Whole is giveable by right.

This is why, despite all the differences, Bergson says, modern metaphysics has flowed and agreed and taken over from old metaphysics instead of breaking with it. [See Image-Movement, pp. 9-10] See, there is indeed something shared between the two methods, the ancient method and the modern method, and yet Bergson reverses everything, and yet we were on the verge of it. As soon as modern science made its power move — linking movement to any-instant-whatever, that is, [Pause] constructing time into an independent variable — something became possible which was not possible for the Ancients. If the movement relates to any-instant-whatever, how can we not see at that point that all that matters is what happens from one instant to another, it’s what which is continued from one instant to another, it’s what grows from one instant to another, it’s what lasts; in other words, is there only the real duration (la durée de réelle)? It is the immobile sections within movement insofar as they related movement to any-instant-whatever that should have been, which could have been able to make us jump into another element, namely the apprehension of what flows, the apprehension of what is continued from one instant to another, the apprehension of the interval from one instant to another, as being the only reality.

In other words, modern science made possible a thought of time, or a thought of duration. It would have been enough if modern science or modern philosophy had agreed to give up the idea that everything is given, that is, that the Whole is giveable. As a result, if I say no, the Whole is not giveable, no, the Whole is not given, what does that mean? Here again, this is so complicated, it’s very good, it gets complicated because the Whole is not giveable, the Whole is not given, it can mean two things: either it means the notion of the Whole has no meaning. There are many modern thinkers who have thought, who have thought that the Whole was a meaningless word; “Whole” meant nothing. That can be stated, but it’s not Bergson’s idea. In short, that’s not it; when he says: “All is not given; all is not giveable”, he does not mean [that] the notion of the Whole is a category of birth; he means the Whole is a perfectly consistent notion, but the Whole is what occurs.

It’s very odd; in the idea of the Whole, he catapults two apparently contradictory ideas at first sight: the idea of a totality and the idea of a fundamental opening. The Whole is the Open, it’s a very weird idea. The Whole is duration; the Whole is what acts, it is what occurs; the Whole is what creates, and created it’s the very fact of duration, that is, it’s the very fact of continuing from one instant to the next instant, the next instant is not being the replica, the repetition of the previous instant. And modern science could have led us to such a thought. It did not do so. It could have given metaphysics a modern sense. And what would it have been? The modern sense of metaphysics is what Bergson is planning to restore, to be the first to restore it, namely a thought of duration.

What does a thought of duration mean? It sounds very abstract, but concretely, it means a thought that takes as its main fundamental question: how can something new be produced? How does the new occur? How is there creation? According to Bergson there is no higher question for thought: how can something new — not huge — how can something new occur in the world? And in some very interesting pages, Bergson ends up saying: This is the touchstone of modern thought. This very odd because when you think about what happened outside of Bergson, all that, one has the impression… and yet he is not the only one; there is a very, very important English philosopher, very brilliant, named [Alfred North] Whitehead at the same time, and the resemblances, the echoes between Whitehead and Bergson are quite large; they knew each other very well, and Whitehead … [1 :45:15]

[Again, Deleuze speaks to someone seated near him]: You are pissing me off, you know; no, it can’t last, you … It’s not that it bothers me, or that it annoys me, but that prevents me from speaking, you understand? As soon as I set my eyes on you, I see your hilarity, whether it’s a tic, or you are laughing deep inside, I don’t care. Put yourself over there. This is very, very annoying for me, a kind of snickering, it’s disturbing; yes, yes, it closes down my thinking … eh, well… [Pause] [1: 45: 50]

Yes, Whitehead is very odd because he constructs concepts, he constructs concepts which seem absolutely necessary to him, even if only for understanding the question. The question is not self-evident; this is a very, very difficult question: what is the meaning of the question? How is it that something new is possible? So, there are people who will say precisely, ah but no! there is nothing new, it is not possible, something new. Okay, fine, well never mind, that’s how it is. There is a certain tone of Bergsonism which is entirely the promotion of this question: how is the appearance of a new equalism possible once the world is given, the space, etc.? It will take all of his philosophy to answer that question, and in fact, it’s a … So, Whitehead is inventing categories; he’s going to call it, he’s inventing a category of creativity. He explains that creativity is the possibility, solely the logical possibility, that something new arises in the world.