December 15, 1988

In the question of friendship, there is a kind of mystery… I mean that it’s closely connected to philosophy. It’s philosophy, as everyone has noted, that introduced this word. I mean that the philosopher is not a wise man (un sage), first because that would make everyone laugh. He presents himself, at the limit, as a friend of wisdom, a friend. What the Greeks invented is not wisdom, but the very strange idea, “friend of wisdom.” What could “friend of wisdom” possibly mean? And that’s the problem of “what is philosophy?”: what does “friend of wisdom” mean? It means that he is not wise, this friend of wisdom. So, obviously, there is an easy interpretation, that he tends toward wisdom, but that doesn’t work.

Seminar Introduction

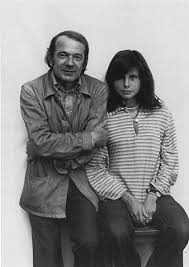

Prior to starting to discuss the first “letter” of his ABC primer from A to Z, “A as in Animal,” with Claire Parnet, Deleuze discusses his understanding of the working premises of this series of interviews:

“You have selected a format as an ABC primer, you have indicated to me some themes, and in this, I do not know exactly what the questions will be, so that I have only been able to think a bit beforehand about the themes. For me, answering a question without having thought about it a bit is something inconceivable. What saves me in this is the particular condition (la clause): should any of this be at all useful, all of it will be used only after my death. So, you understand, I feel myself being reduced to the state of a pure archive for Pierre-André Boutang, to a sheet of paper [Parnet laughs in the mirror reflection], so that lifts my spirits and comforts me immensely, and nearly in the state of pure spirit (pur esprit), I speak after my death, and we know well that a pure spirit finally can make tables turn. But we know as well that a pure spirit is not someone who gives answers that are either very profound or very intelligent. So anything goes in this, let’s begin, A-B-C, whatever you want.”

English Translation

In this first segment of L’Abécédaire, Deleuze starts with “A as in Animal” (instead of A as in “amitié”, or friendship, which might have been preferable), then after a brief, somewhat personal reflection on “B as in Boire [Drinking]”, he reflects at length on “C as in Culture” (in various senses of the term). Then he pursues the all-important “D as in Desire,” followed by an exploration of his education and other aspects of childhood in “E as in Enfance [Childhood]”, and finally, “F as in Fidélité [Loyalty]” , the consideration of friendship.

While no dates are provided for the filming, an internal reference (to the Armenian earthquake that occurred on 7 December 1988, mentioned “G as in Gauche“) helps situate the first day of filming, situated here a bit arbitrarily as 15 December 1988. Please note that, following Deleuze’s wish that no transcript be published, we do not provide a transcript pdf.

Download

L’Abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze, avec Claire Parnet

Directed by Pierre-André Boutang (1996)

Credits (shown at the end of each tape):

Conversation: Claire Parnet

Direction: Pierre-André Boutang, Michel Pamart

Image: Alain Thiollet

Sound: Jean Maini

Editing: Nedjma Scialom

Sound Mix: Vianney Aubé, Rémi Stengel

Images from Vincennes: Marielle Burkhalter

—————————————————————————

Translation & Notes: Charles J. Stivale

Prelude[1]

A short description of the trailer and then of the interview “set” is quite useful: the black and white trailer over which the title, then the director’s credit are shown, depicts Deleuze lecturing to a crowded, smoky seminar, his voice barely audible over the musical accompaniment. The subtitle, “Université de Vincennes, 1980,” appears briefly at the lower right, and Deleuze’s desk is packed with tape recorders. A second shot is a close-up of Deleuze chatting with the students seated closest to him. Then another shot shows students in the seminar listening intently, most of them (including a young Claire Parnet in profile) smoking cigarettes. The final shot again shows Deleuze lecturing from his desk at the front of the seminar room, gesticulating as he speaks. The final gesture shows him placing his hand over his chin in a freeze-frame, punctuating the point he has just made.

As for the setting in Deleuze’s apartment during the interview, the viewer sees Deleuze seated in front of a sideboard over which hangs a mirror, and opposite him sits Parnet, smoking constantly throughout. On the dresser to the right of the mirror is his trademark hat perched on a hook. The camera is located behind Parnet’s left shoulder so that, depending on the camera focus, she is partially visible from behind and with a wider focus, visible in the mirror as well, at least during the first day of shooting. The production quality is quite good, and in the three-cassette collection now commercially available, Boutang chose not to edit out the jumps between cassette changes. On occasion, these interruptions cause Deleuze to lose his train of thought, but usually he is able to pick up where he left off with a prompt from Parnet.

[Prior to starting to discuss the first “letter” of his ABC primer, “A as in Animal,” Deleuze discusses his understanding of the working premises of this series of interviews]

Deleuze: You have selected a format as an ABC primer, you have indicated to me some themes, and in this, I do not know exactly what the questions will be, so that I have only been able to think a bit beforehand about the themes. For me, answering a question without having thought about it a bit is something inconceivable. What saves me in this is the particular condition (la clause): should any of this be at all useful, all of it will be used only after my death. So, you understand, I feel myself being reduced to the state of a pure archive for Pierre-André Boutang, to a sheet of paper [Parnet laughs in the mirror reflection], so that lifts my spirits and comforts me immensely, and nearly in the state of pure spirit (pur esprit), I speak after my death, and we know well that a pure spirit finally can make tables turn. But we know as well that a pure spirit is not someone who gives answers that are either very profound or very intelligent. So anything goes in this, let’s begin, A-B-C, whatever you want.

“A as in Animal”

Parnet: We begin with “A,” and “A” is “Animal.” We can cite, as if it were you saying it, a quote from W.C. Fields: “A man who doesn’t like animals or children can’t be all bad.” [Deleuze chuckles] We’ll leave aside the children for the moment, but domestic animals, I know that you don’t care for them much. And in this, you don’t even accept the distinction made by Baudelaire and Cocteau — cats are not any better than dogs for you. On the other hand, throughout your work, there is a bestiary that is quite repugnant; that is, besides deers (fauves) that are noble animals, you talk copiously of ticks, of fleas, of a certain number of repugnant little animals of this kind. What I want to add is that animals have been very useful in your writings, starting with Anti-Oedipus, through a concept that has become quite important, the concept of “becoming-animal” (devenir-animal). So I would like to know a bit more clearly what is your relationship to animals.

[Throughout this question, Deleuze sits smiling, but moving uncomfortably in his seat as if he were undergoing some ordeal]

Deleuze: What you said there about my relation with domestic animals… It’s not really domestic, or tamed, or wild animals that concern me, cats or dogs. . . . The problem, rather, is with animals that are both familiar and familial. Familiar or familial animals, tamed and domesticated, I don’t care for them, whereas domesticated animals that are not familiar and familial, I like them fine because I am quite sensitive to something in these animals. What happened to me is what happens in lots of families, there is neither dog nor cat, and then one of our children, Fanny’s and mine, came home with a tiny cat, no bigger than his little hand, that he found out in the country somewhere, in a basket or somewhere, and from that fatal moment onward, I have always had a cat around the house. What do I find unpleasant in this — although that certainly was no major ordeal – what do I find unpleasant? I don’t like things that rub against me (les frotteurs) … and a cat spends its time rubbing up against you. I don’t like that, and with dogs, it’s altogether different: what I fundamentally reproach them for is always barking. A bark really seems to me the stupidest cry… There are animal cries in nature, a variety of cries, and barking is truly the shame of the animal kingdom. Whereas I can stand much better (on the condition that it not be for too long a time) the howling at the moon, a dog howling at the moon…

Parnet : … at death…

Deleuze: … At death, who knows? I can stand this better than barking. And since I learned quite recently that cats and dogs were cheating the Social Security system, my antipathy has increased even more.

[Deleuze has a wry smile in saying this, at some private joke, that he may or may not share with Parnet and that remains unexplained]

Deleuze: What I mean is… What I am going to say is completely idiotic because people who really like cats and dogs obviously do have a relationship with them that is not human. For example, you see that children do not have a human relationship with a cat, but rather an infantile relationship with animals. What is really important is for people to have an animal relationship with an animal. So what does it mean to have an animal relationship with an animal? It doesn’t consist of talking to it… but in any case, I can’t stand the human relationship with the animal. I know what I am saying because I live on a rather deserted street where people walk their dogs, and what I hear from my window is quite frightening, the way that people talk to their animals. Even psychoanalysis notices this! Psychoanalysis is so fixated on familiar or familial animals, on animals of the family, that any animal dream is interpreted by psychoanalysis as being an image of the father, mother, or child, that is, an animal as a family member. I find that odious, I can’t stand it, and you only have to think of two paintings by the Douanier [Henri Julien Félix] Rousseau, the dog in the cart (carriole) who is truly the grandfather, the grandfather in a pure state, and the war horse (le cheval de guerre) who is a veritable beast (bête).[2] So the question is, what kind of relationship do you have with an animal? If you have a human relationship with an animal . . . [Deleuze shakes his head] [3]

But again, generally people who like animals don’t have a human relationship with animals, they have an animal relationship with the animal, and that’s quite beautiful. Even hunters – and I don’t like hunters – but even hunters have an astonishing relationship with the animal… Yeh … [Deleuze pauses]

And you asked me also … Well, other animals, it’s true that I am fascinated by animals (bêtes) like spiders, ticks, fleas … They are as important as dogs and cats. [Parnet laughs] And there are relationships with animals there, someone who has tics, who has fleas, what does that mean? These are relationships with some very active animals. So what fascinates me in animals? Because really, my hatred for certain animals is nourished by my fascination with many other animals. If I try to take stock vaguely of this, what is it that impresses me in an animal? The first thing that impresses me is the fact that every animal has a world, and it’s curious because there are a lot of humans, a lot of people who do not have a world. They live the life of everybody, [Deleuze chuckles] that is, of just any one and any thing. Animals, they have worlds.

What is an animal world? It’s sometimes extraordinarily limited, and that’s what moves me. Finally, animals react to very few things… [To Parnet]: Cut me off if you see that …

[Change of cassette; the producer claps his hand while the director announces: “Gilles Deleuze, cassette two”]

Deleuze: Yes, so, in this story of the first characteristic of the animal, it’s really the existence of specific, special animal worlds. Perhaps it is sometimes the poverty of these worlds, the reduced character of these worlds, that impresses me so much. For example, oh, we were talking earlier about an animal like the tick. The tick responds, reacts to three things, three stimuli, period, that’s it, in a natural world that is immense, three stimuli, that’s it: that is, it tends toward the extremity of a tree branch, it’s attracted by light, it can wait on top of this branch, it can wait for years without eating, without anything, in a completely amorphous state. It waits for a ruminant, an herbivore, an animal to pass under its branch, it lets itself fall… It’s a kind of olfactory stimulus… the tick smells, it smells the animal that passes under its branch, that’s the second stimulus: light first, then odor. Then, when it falls onto the back of the poor animal, it goes looking for the region that is the least covered with hair… So, there’s a tactile stimulus, and it digs in under the skin. For everything else, if one can say this, for everything else, it does not give a damn (elle s’en fout complètement)… That is, in a nature teeming [with life], it extracts, selects three things.

Parnet: And is that your life’s dream? [Parnet laughs, smiling at Deleuze] That’s what attracts you to animals?

Deleuze: [He smiles, but continues] That’s what constitutes a world, that’s what constitutes a world.

Parnet: Hence, your animal-writing relationship, that is, the writer, for you, is also someone who has a world…

Deleuze: It’s more compl… Yes, I don’t know… because there are other aspects: it is not enough to have a world to be an animal. What fascinates me completely are territorial matters (des affaires de territoire). With Félix [Guattari], we really created a concept, nearly a philosophical concept, with the idea of territory. Animals with territory — ok, there are animals without territory, fine – but animals with territory, it’s amazing because constituting a territory is, for me, nearly the birth of art. How an animal marks its territory, everyone knows, everyone always invokes stories of anal glands, of urine, of… with which it marks the borders of its territory. But it’s a lot more than that: what intervenes in marking a territory is also a series of postures, for example, lowering oneself/lifting oneself up; a series of colors, baboons (les drills), for example, the color of buttocks of baboons that they display at the border of territories… Color, song (chant), posture: these are the three determinants of art: I mean, color and lines — animal postures are sometimes veritable lines – color, line, song – that’s art in its pure state.

And so, I tell myself that when they leave their territory or return to their territory, it’s in the domain of property and ownership (l’avoir). It’s very curious that it is in the domain of property and ownership, that is, “my properties,” in the manner of Beckett or Michaux. Territory constitutes the properties of the animal, and leaving the territory, they risk it, and there are animals that recognize their partner, they recognize them in the territory, but not outside the territory. That’s what I call a marvel…[4]

Parnet: Which one?

Deleuze: I don’t recall which bird, you have to believe me on this…

So, with Félix – I am leaving the animal subject, I pass on to a philosophical question because we can mix all kinds of things in the Abécédaire. I tell myself: philosophers sometimes get criticized for creating barbaric words (mots barbares). But, put yourself in my place: for certain reasons, I am interested in reflecting on this notion of territory, and I tell myself, territory has no term for the relation to a movement by which one leaves the territory. So, to address this, I need a word that is apparently “barbaric.” Henceforth, with Félix, we constructed a concept that I like a lot, the concept of “deterritorialization.” [Parnet speaks the word along with Deleuze]

We’ve been told that it’s a hard word to pronounce, and then asked what it means, what its use is… So, this is a beautiful case of a philosophical concept that can only be designated by a word that does not yet exist, even if we find subsequently that there are equivalents in other languages. For example, I happened to notice that in Melville, there appears all the time “outlandish” – I pronounce poorly, you can correct it yourself – but “outlandish” is precisely the equivalent of “the deterritorialized,” word for word.[5] So, I tell myself that for philosophy – before returning to animals – for philosophy, it is quite striking: the invention of a barbaric word is sometimes necessary to take account of a notion with innovative pretensions: the notion with innovative pretensions is that there is no territory, territorialization without a vector of exiting the territory; there is no exiting the territory, that is, deterritorialization, without at the same time an effort of reterritorializing oneself elsewhere, which is something else.

All this functions with animals, and that’s what fascinates me. What is fascinating generally is the whole domain of signs. Animals emit signs, they ceaselessly emit signs, they produce signs. That is, in the double sense, they react to signs – for example, a spider, everything that touches its web, it reacts to anything, reacts to signs – and they produce signs – for example, the famous sign, is that a wolf sign, a wolf track or something else? I admire enormously people who know how to recognize [tracks], for example, hunters – real hunters, not hunt club hunters, but real hunters who can recognize the animal that has passed by. At that point, they are animal, they have with the animal an animal relationship. That’s what I mean by having an animal relationship with an animal. It’s really amazing.[6]

Parnet: And this emission of signs, this reception of signs, is there a connection with writing and the writer, and the animal?

Deleuze: Of course. If someone were to ask me what it means to be an animal, I would answer: it’s “l’être aux aguets”, the being on the lookout. It’s a being fundamentally on the lookout.

Parnet: Like the writer?

Deleuze: The writer, well, yes, on the lookout, the philosopher, on the lookout, obviously, we are on the lookout. For me, you see, the ears of the animal: it does nothing without being on the lookout, it’s never relaxed, an animal. It’s eating, [yet] has to be on the lookout to see if something is happening behind its back, on either side, etc. It’s terrible, this existence “aux aguets.”

So, you make the connection with the writer, what is the relation between the animal and the writer…?

Parnet: … you made it before I did…

Deleuze: That’s true… One almost has to say that, at the limit… A writer, what is it? He writes, he writes “for” readers, of course, but what does “for” mean? It means “à l’intention de,” toward them, intended toward them, one writes “for” readers. But one has to say that the writer writes also for non-readers, that is, not intended for them\but “in their place.” So, it means two things: intended for them and in their place. Artaud wrote pages that nearly everyone knows, “I write for the illiterate, I write for idiots.” Faulkner writes for idiots. That doesn’t mean so that idiots would read, that the illiterate would read, it means “in the place of” the illiterate. I mean, I write “in the place of” barbarians (les sauvages), I write “in the place of” animals.[7]

And what does that mean? Why does one dare say something like that, I write in the place of idiots, the illiterate, animals? Because that is what one does, literally, when one writes. When one writes, one is not pursuing some private little affair. They really are stupid fools (connards); really, it’s the abomination of literary mediocrity, in every era, but particularly quite recently, that makes people believe that to create a novel, for example, it suffices to have some little private affair, some little personal affair – one’s grandmother who died of cancer, or someone’s personal love affair — and there you go, you can write a novel based on this. It’s shameful to think things like that. Writing is not anyone’s private affair, but rather it means throwing oneself into a universal affair, be it a novel or philosophy. Now what does that mean?

[Change of cassette; the producer claps his hand while the director announces: “Gilles Deleuze, cassette three”]

Parnet: So, this “writing for,” that is, “intended for” or “in the place of,” it’s a bit like what you said in A Thousand Plateaus about [Lord] Chandos by Hofmannsthal, in the very beautiful phrase: “the writer is a sorcerer because he sees the animal as the only population before which he is responsible.”[8]

Deleuze: That’s it, absolutely right. And for a very simple reason, I think it’s quite simple… It’s not at all a literary declaration what you just read from Hofmannsthal, it’s something else. Writing means necessarily pushing language – and pushing syntax, since language is syntax – up to a certain limit (limite), a limit that can be expressed in several ways: it can be just as well the limit that separates language from silence, or the limit that separates language from music, or the limit that separates language from something that would be, what? Let’s say, the wailing, the painful wailing…

Parnet: But not the barking, surely!

Deleuze: Oh, no, not barking, although who knows? There might be a writer who is capable…. The painful wailing? Well, everyone says, why yes, it’s Kafka, it’s Metamorphosis, the manager who cries out, “Did you hear? It sounds like an animal,” the painful wailing of Gregor. Or else the mouse folk,

Parnet: “Josephine”.[9]

Deleuze: … one writes for the mouse folk, the rat folk that are dying because, contrary to what is said, it’s not men who know how to die, but beasts (bêtes), and when men die, they die like animals. Here we return to cats, and I have a lot of respect… Among the many cats that lived here, there was that little cat who died rather quickly, that is, I saw what a lot of people have seen as well, how an animal seeks a corner to die in… There is a territory for death as well, a search for a territory of death, where one can die. We saw the little cat trying to slide itself right into a tight corner, an angle, as if it were the good spot for it to die in.

So, in a sense, if the writer is indeed one who pushes language to the limit, the limit that separates language from animality, that separates language from the cry, that separates language from the song/chant (chant), then one has to say, yes, the writer is responsible to animals who die, that is, he answers to animals who die, to write, literally, not “for” them – again, I don’t write “for” my dog or for my cat –, but writing “in the place of” animals who die, etc., carrying language to this limit. There is no literature that does not carry language and syntax to this limit that separates man from animal… One has to be on this limit…. That’s what I think…

Even when one does philosophy, that’s the case… One is on the limit that separates thought from non-thought. You always have to be at the limit that separates you from animality, but precisely in such a way that you are no longer separated from it. There is an inhumanity proper to the human body, and to the human mind, there are animal relations with the animal…

And if we were finished with “A”, that would be nice…

“B as in Boire/Boisson [Drink]”

Parnet: OK, then, we will pass on to “B”. “B” is a little bit special, it’s on drinking (la boisson).[10] OK, so you used to drink, and then stopped drinking, [Deleuze smiles] and I would like to know what it was for you to drink when you used to drink… Was it for pleasure?

Deleuze: Yeh, I drank a lot… I drank a lot… So, I stopped, but I drank a lot… What was it? [Deleuze laughs] That’s not difficult, at least I think not… You should question other people who drank a lot, you should question alcoholics. I believe that drinking is a matter of quantity. For that reason, there is no equivalent with food, even if there are people who eat copiously (gros mangeurs) — that always disgusted me, so that’s not relevant in my case. But drinking… I understand well that one doesn’t drink just anything, that each drinker has a favorite drink, but it’s because in that framework that one has to grasp the quantity.

What does this question of quantity mean? People make fun of addicts and alcoholics because they never stop saying, “Oh you know, I am in control, I can stop drinking whenever I want.” People make fun of them because they don’t understand what drinkers mean. I have some very clear memories of this, I think everyone who drank understands this. When you drink, what you want to reach is the last drink (dernier verre). Literally, drinking means doing everything in order to reach the final drink. That’s what is interesting.

Parnet: That’s always the limit (limite)?

Deleuze [laughs]: Well, what the limit is is very complicated, let me tell you… In other words, an alcoholic is someone who never ceases to stop drinking, I mean, who never stops having arrived at the last drink. So, what does that mean? It’s like the expression by [Charles] Péguy that is so beautiful, “It’s not the final water lily that repeats the first, it’s the first water lily that repeats all the others and the final one.” The first drink, it repeats the last one, it’s the last one that counts.

So, what does that mean, the last drink, for an alcoholic? He gets up in the morning, if he’s a morning alcoholic – there are all the kinds that you might want –, if he’s a morning alcoholic, he is entirely pointed toward the moment when he will reach the last drink. It’s not the first, the second, the third that interests him… It’s a lot more… He’s clever, full of guile, an alcoholic… The last glass means this: he evaluates… there is an evaluation. He evaluates what he can hold, without collapsing… he evaluates… It varies considerably with each person. So, he evaluates the last drink, and all the others are going to be his way of passing, of reaching the last glass.

And what does “the last” mean? That means that he cannot stand to drink one more glass that particular day. It’s the last one that will allow him to begin drinking the next day… because if he goes all the way to the last drink, on the contrary, that goes beyond his power/capacity (pouvoir), it’s the last in his power. If he goes beyond the last one in his power in order to reach the last one beyond his power, then he collapses, then he’s screwed (foutu), he has to go to the hospital, or he has to change his habits, he has to change assemblages. So that when he says, “the last drink,” it’s not the last one, it’s the next-to-last one. He is searching for the next-to-last one. In other words, there is a term to say the next-to-last, it’s penultimate… He does not seek the last drink, he seeks the penultimate one. Not the ultimate, because the ultimate [Deleuze gestures with his hands] would place him outside his arrangement. The penultimate is the last one… before beginning again the next day.

So I can say that the alcoholic is someone who says, and who never stops saying — You hear it in the cafés, those groups of alcoholics are so joyful, one never gets tired of listening to them — So the alcoholic is someone who never stops saying, “OK, it’s the last one”, and the last one varies from one person to another, but the last one is the next-to-last one.

Parnet: And he’s also the one who says, “I’m stopping tomorrow.”

Deleuze: “Stopping tomorrow”? No, he never says “I’m stopping tomorrow.” He says, “I’m stopping today”, to be able to start over again tomorrow.

Parnet: And since drinking means not stopping… means stopping drinking constantly, then how does one stop drinking completely, because you stopped drinking completely…?

Deleuze: It’s too dangerous, if one goes too quickly. Michaux has said everything on that topic. In my opinion, drug problems and alcohol problems are not that separate. Michaux said everything on that topic…[11] A moment comes when it is too dangerous.

Here again, there is this ridge (crête)… when I was talking about this ridge between language and silence, or language and animality. This ridge is a thin division. One can very well drink or take drugs… One can always do whatever one wants if it doesn’t prevent you from working. If it’s a stimulus… It’s even normal to offer something of one’s body as a sacrifice. There is a whole sacred, sacrificial attitude in these activities, drinking, taking drugs, one offers one’s body as a sacrifice… Why? No doubt because there is something entirely too strong that one could not stand without alcohol. It’s not a question of being able to stand alcohol… That’s perhaps what one believes, what one needs to believe, what one believes oneself to see, to feel, to think, with the result that one has the need in order to stand it, in order to master it, one needs assistance, from alcohol, drugs, etc.

[Change of cassette, Boutang: “Gilles Deleuze” (cassette 4), clap; the producer claps his hands]

Deleuze: So, the question of limits, it’s quite simple… Drinking, taking drugs, these are almost supposed to make possible something that is too strong, even if one has to pay for it afterwards, that’s well known. But it’s connected to working, working. And it’s obvious that when everything is reversed and drinking prevents one from working, when taking a drug becomes a way of not working, that’s the absolute danger, it no longer has any interest. And at the same time, it’s more and more obvious that although we used to think drinking was necessary, that taking drugs was necessary, they are not necessary… Perhaps one has to have gone through that experience to realize that everything one thought one did thanks to drugs or thanks to alcohol, one could do without them.

You see, I admire a lot the way that Michaux considers all this… He stops. So for me, there is less merit since I stopped drinking for reasons related to breathing, for health reasons. It is obvious that one has to stop or do without it. The only tiny justification possible would be if they did help one to work, even if one has to pay for it physically afterwards. But the more one continues, the more one realizes that it doesn’t help one’s work, so…

Parnet: But on one hand, Michaux must have drunk quite a lot and taken a lot of drugs in order to get to the point of doing without in such a state as he did…

Deleuze: Yeh, yeh…

Parnet: And on the other hand, you said that when you drink, it must not prevent you from working, but that you perceive something that drinking helps you to support, and this “something” is not life… so that raises the question about the writers you prefer…

Deleuze: On the contrary, it is life…

Parnet: It is life?

Deleuze: It’s something too strong in life. It’s not necessarily something that is terrifying, just something that is too strong, it’s something too powerful in life. Some people believe a bit idiotically that drinking puts you on the level of this too-powerful-something. If you take the whole lineage of the Americans, the great American writers…

Parnet: From Fitzgerald to Lowry…

Deleuze: From Fitzgerald to the one I admire the most is Thomas Wolfe… all that is a series of alcoholics, at the same time, that’s what allows them… no doubt, helps them to perceive this something-too-huge…

Parnet: Yes, but it’s also because they themselves had perceived something powerful in life that not everyone could perceive, they felt something powerful in life…

Deleuze: That’s right, that’s right, obviously… It’s not alcohol that is going to make you feel something.

Parnet: … the power of life for them that they alone could perceive.

Deleuze: I completely agree … I completely agree …

Parnet: And the same for Lowry…

Deleuze: I completely agree … Certainly… They created their works (une oeuvre), and what alcohol was for them, well, they took a risk, they took a chance on it because they thought, right or wrong, that alcohol would help them with it. I had the feeling that alcohol helped me create concepts… It’s strange… philosophical concepts, yes, that it helped me, and then it wasn’t helping me any more, it was getting dangerous for me, I no longer wanted to work. At that point, you just have to give it up, that’s all…

Parnet: That’s more like an American tradition, because we don’t know of many French writers who have this penchant for alcohol, and still it’s kind of hard to… There is something that separates their writing from the States and alcohol…

Deleuze: Well, yes, yes, but French writers, it’s not the same vision of writing… I don’t know… If I have been influenced so much by the Americans, it’s because of this question of vision. They are “seers” (des voyants) … If one believes that philosophy, writing, is a question, in a very modest fashion, a question of “seeing” something… seeing something that others don’t see, then it’s not exactly the French conception of literature. Although there are a lot of alcoholics in France…

Parnet: But the alcoholics in France, they stop writing. Blondin has a lot of problems, at least from what we can tell.[12] [Parnet laughs, Deleuze smiles] But we don’t know of many philosophers either who have recounted their penchant for alcohol.

Deleuze: Verlaine lived on a street right nearby here, rue Nollet…

Parnet: Ah yes, with the exception of Rimbaud and Verlaine…

Deleuze: … and it wrenches my heart because when I walk long rue Nollet, I think that it undoubtedly must have been the route that Verlaine took to go to a café to drink his absinthe… Apparently, he lived in a pitiful apartment, all that so…

Parnet: Well, yes, poets and alcohol…

Deleuze: … One of France’s greatest poets who used to shuffle down that street… It’s marvelous… Yes, yes…

Parnet: To the bar, Le Bar des Amis.

Deleuze: Yes, no doubt! [Deleuze laughs]

Parnet: Yes, among poets, we know that there were more alcoholics … Ok, well, we have finished with alcohol…

Deleuze: Yep, we’ve finished “B”. My, my, we’re speeding along…

“C as in Culture”

Parnet: … so we pass on to “C”, and “C” is vast…

Deleuze: What is it?

Parnet: “C as in Culture.”

Deleuze: Sure, why not?

Parnet: OK, you are someone who describes himself as not “cultivated” (pas cultivé). That is, you say that you read, you go to movies, you observe things to gain particular knowledge, something that you need for a particular, ongoing project that you are in the process of developing. But, at the same time, [Deleuze listens very attentively] you are someone who, every Saturday, goes out to an art exhibit, goes out to a movie, in the broad cultural domain… One gets the impression that you have a kind of practice, a huge effort in culture, [Deleuze smiles, listens with evident fascination] that you systematize, and that you have a cultural practice, that is, you go out, you make an effort at a systematic cultural practice, you aim at developing yourself culturally (te cultiver). And yet, I repeat, you claim that you are not at all “cultivated,” so how do you explain this little paradox?… You’re not “cultivated”?

Deleuze: No, because… I would say that, in fact… When I tell you that, I don’t see myself, really, I don’t experience myself (je ne me vis pas) as an intellectual or experience myself as “cultivated” for a simple reason: when I see someone “cultivated,” I am terrified, and not necessarily with admiration, although admiring them from certain perspectives, from others, not at all. But I am just terrified of a “cultivated person,” and this is quite obvious to “cultivated people” (gens cultivés). It’s a kind of knowledge, a frightening body of knowledge especially (savoir effarant) … One sees that a lot with intellectuals, they know everything. Well, maybe not, but they are informed about everything – they know the history of Italy during the Renaissance, they know the geography of the North Pole, they know… the whole list, they know everything, can talk about anything… It’s abominable.

So, when I say that I am neither “cultivated,” nor an intellectual, I mean something quite simple, that I have no “reserve knowledge” (aucun savoir de réserve), no… There’s no problem, at my death, there’s no point in looking for what I have left to publish… Nothing, nothing, because I have no reserves, I have no provisions, no provisional knowledge. And everything that I learn, I learn for a particular task, and once it’s done, I immediately forget it, so that if ten years later, I have to – and this gives me great joy — if I have to get involved with something close to or directly within the same subject, I would have to start again from zero, except in certain very rare cases, for example Spinoza, whom I don’t forget, who is in my heart and in my mind. Otherwise… [13] So, why don’t I admire this “frightening knowledge,” these people who talk…?

Parnet: Is this knowledge a kind of erudition, or just an opinion on every subject?

Deleuze: No, it’s not erudition. They know… they know how to talk about it. First, they’ve traveled a lot, traveled in geography, in history, but they know how to talk about everything. I’ve heard them on TV, it’s frightening… I have heard… well, since I am full of admiration for him, I can even say it, people like Eco, Umberto Eco… It’s amazing… There you go, it’s like pushing on a button, and he knows all of it as well. I can’t say that I envy that entirely, I’m just frightened by it, but I don’t envy it at all.

To a certain extent, I ask: what does culture consist of? And I tell myself that it consists a lot in talking. I can’t keep myself… Especially since I have stopped teaching, since I have retired, I realize that talking is a bit dirty, a bit dirty, whereas writing is clean. Writing is clean and talking is dirty. It’s dirty because it means being seductive (faire du charme). I could never stand attending colloquia ever since I was in school, still quite young, I could never stand colloquia. I don’t travel much, and why not? Intellectuals… I would gladly travel sometime if… Well, actually I wouldn’t travel, my health prevents it, but intellectuals travelling is a joke (une bouffonnerie). They don’t travel, they move about in order to go talk… They go from one place where they talk in order to go to another place where they are going to talk even during meals, they talk with the local intellectuals. They never stop talking, and I can’t stand talking, talking, talking, I can’t stand it. So, in my opinion, since culture is closely linked to speaking (la parole), in this sense, I hate culture (je hais la culture), I cannot stand it.

Parent: Well, we will come back to the separation between writing itself and dirty speech because, nonetheless, you are a very great professor and…

Deleuze: Well, that’s different…

Parnet: … and we will come back to it because the letter “P” is about your work as professor, and then we will be able to discuss “seduction”…

[Change of cassette; the producer claps his hand while the director announces: “Gilles Deleuze, cassette five”]

Parnet: I still want to come back to this subject that you kind of avoided, to this effort, discipline even, that you impose on yourself — even if, in fact, you don’t need to — to see, well, for example, in the last two weeks, the [Sigmar] Polke exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. You go out rather frequently, not to say on a weekly basis, to see a major film or to see art exhibits. So, you say that you are not erudite, not “cultivated,” you have no admiration for “cultivated people,” like you ust said, so what does this practice, all this effort, correspond to for you? Is it a form of pleasure?

Deleuze: I think… Yes, certainly, it’s a form of pleasure, although not always. But I see this as part of my investment in being “on the lookout” (être aux aguets) [see “A as in Animal”]. I don’t believe in culture, to some extent, but rather I believe in encounters (rencontres). But these encounters don’t occur with people. People always think that it’s with people that encounters occur, which is why it’s awful… Now, in this, that belongs to the domain of culture, intellectuals meeting one another, this disgusting practice of conferences (cette saleté de colloque), this infamy. So, encounters, it’s not between people that they happen, but with things… So, I encounter a…. painting, yes, or a piece of music, that’s how I understand an encounter. When people want to connect encounters to themselves, with people, well, that doesn’t work at all… That’s not an encounter, and that’s why encounters are so utterly, utterly disappointing. Encounters with people are always catastrophic.

So, as you said, when I go out on Saturdays and Sundays, to the movies, etc., I’m not certain to have an encounter… I go out, I am “on the lookout” for encounters, wondering if there might be material for an encounter, in a film, in a painting, so it’s great. I’ll give an example because, for me, whenever one does something, it is also a question of moving on from it, getting out of or beyond it (d’en sortir), simultaneously staying in it and getting out of it. So, staying in philosophy also means how to get out of philosophy. But getting out of philosophy doesn’t mean doing something else. One has to get out while remaining within… It’s not doing something else, not writing a novel. First off, I wouldn’t be able to in any event, but even if I could, it would be completely useless. I want to get out of philosophy by means of philosophy. That’s what interests me…

Parnet: That is…?

Deleuze: Here is an example. Since all this will be after my death, I can speak without modesty. I just wrote a book on a great philosopher called Leibniz in which I insisted on the notion that seemed important in his work, but that is very important for me, the notion of “the fold.” So, I consider that it’s a book of philosophy, on this bizarre little notion of the fold. What happens to me after that? I received a lot of letters, as always… There are letters that are insignificant even if they are charming and affectionate and move me deeply, others that talk about what I have done… letters from intellectuals who liked or didn’t like the book…

Then I receive two other letters that make me rub my eyes in disbelief. A letter from people who tell me, “Your story of folds, that’s us!” and I realize that it’s from people who belong to an association that has 400 members in France currently, perhaps they now have more, an association of paper folders. They have a journal, and they send me the journal, and they say, “We agree completely, what you are doing is what we do.” So, I tell myself, that’s quite something! Then I received another kind of letter, and they speak in exactly the same way, saying: “The fold is us!”

I find this marvelous, all the more so because it reminded me of a story in Plato, since great philosophers do not write in abstractions, but are great writers and authors of very concrete things. So, in Plato, there is a story that delights me, and it’s no doubt linked to the beginning of philosophy, maybe we will come back to it… Plato’s topic is… He gives a definition, for example, what is a politician? A politician is the pastor of men (pasteur des hommes). And with that definition, lots of people arrive to say: “Hey, you can see, we are politicians!” For example, the shepherd arrives, says “I dress people, so I am the true pastor of men”; the butcher arrives, “I feed people, so I am the true pastor of men.” So, these rivals arrive.

And I feel like I have been through this a bit: here come the paper folders who say, we are the fold! And the others who wrote and who sent me exactly the same thing, it’s really great, they were surfers who, it would seem, have no relation whatsoever with the paper folders. And the surfers say, “We understand, we agree completely because what do we do? We never stop inserting ourselves into the folds of nature. For us, nature is an aggregate of mobile folds, and we insert ourselves into the fold of the wave, live in the fold of the wave, that’s what our task is. Living in the fold of the wave.” And, in fact, they talk about this quite admirably. These people are quite… They think about what they do, not just surfing, but think about what they do, and maybe we will talk about it one day if we reach “Sports”, at “S”. [“T as in Tennis”]

Parnet: So, these belong to the “encounter” category, these encounters with surfers, with paper folders?

Deleuze: Yes, these are encounters. When I say “get out of philosophy through philosophy,” this happened to me all the time… I encountered the paper folders… I don’t have to go see them. No doubt, we’d be disappointed, I’d be disappointed, and they certainly would be even more disappointed, so no need to see them. I had an encounter with the surf, with the paper folders, literally, I went beyond philosophy by means of philosophy. That’s what an encounter is. So, I think, when I go out to an exhibit, I am “on the lookout,” searching for a painting that might touch me, that might affect me. [Same] when I go to the movies… I don’t go to the theater because theater is too long, too disciplined, it’s too… it’s too… it does not seem to be an art that… except in certain cases, except with Bob Wilson and Carmelo Bene, I don’t feel that theater is very much in touch with our era, except for these extreme cases.[14] But to remain there for four hours in an uncomfortable seat, I can’t do it any more for health reasons, so that wipes theater out entirely for me. But at a painting exhibit or at the movies, I always have the impression that in the best circumstances, I risk having an encounter with an idea…

Parnet: Yes, but there is no… I mean, films only for entertainment (distraction) do not exist at all?

Deleuze: Well, they are not culture…

Parnet: They may not be culture, but there is no entertainment…

Deleuze: Well, entertainment (la distraction)…

Parnet: … that is, everything is situated within your work?

Deleuze: No, it’ not work, it’s just that I am “on the lookout” for something that might “pass” (quelque chose qui passe), asking myself, does that disturb me (est-ce que ça me trouble)? Those [kinds of films]… they amuse me a lot, they are very funny.

Parnet: Well, it’s not Eddie Murphy who is going to disturb you!

Deleuze: It’s not…?

Parnet: Eddie Murphy, he’s a director… no, an American comedian and actor whose recent films are enormously successful with the public.

Deleuze: I don’t know him.

Parnet: No, I mean, you never watch… no, you only watch Benny Hill on television…

Deleuze [smiling]: Yes, well, I find Benny Hill interesting, that interests me. Well, it’s certainly nothing that is necessarily really good or new, but there are reasons why it interests me.

Parnet: But when you go out, it’s for an encounter.

Deleuze: When I go out … if there is no idea to draw from it, if I don’t say, “Yes, he had an idea”… What do great filmmakers do? This is valid for filmmakers too. What strikes me in the beauty of, for example, a great filmmaker like Minnelli, or like [Joseph] Losey, what affects me if not that they are overwhelmed by ideas, an idea…

Parnet [interrupting]: You’re starting in on my [letter] “I”! Stop right away! You’re starting in on my [letter] “I”!

Deleuze: Ok, let’s stop on that, but that’s what an encounter is for me, one has encounters with things and not with people…

Parnet: Do you have a lot of encounters, to talk about a particular cultural period like right now?

Deleuze: Well, yes, I just told you, with paper folders, with surfers… What could you ask for that’s more beautiful?

Parnet: But…

Deleuze: But these are not encounters with intellectuals, I don’t have any encounters with intellectuals…

Parnet: But do you…

Deleuze: … or if I have an encounter with an intellectual, it’s for other reasons, like I like him so I have a meeting with him, for what he is doing, for his ongoing work, his charm, all that… One has an encounter with those kinds of elements, the charm of people, with the work of people, but not with people in themselves. I don’t have anything to do with people, nothing at all (Je n’ai rien à foutre avec les gens, rien du tout). [Deleuze pauses]

Parnet: Perhaps they rub up against you like cats.

Deleuze: Well yes, if that’s how it was, if there’s rubbing or barking, it’s awful!

[Change of cassette (cassette 6); the producer claps his hand]

Parnet: Let’s think about culturally rich and culturally poor periods. [Deleuze rubs his eyes as Parnet speaks] So what about now, do you think it’s a period that’s not too rich, because I often see you get very annoyed watching television, watching the literary shows that we won’t name, although when this interview is shown, the names will have changed. [Parnet and Deleuze smile at some shared joke as she speaks] Do you find this to be a rich period or a particularly poor period that we are living through?

Deleuze: [Deleuze laughs, and Parnet along with him] Yes, it’s poor, it’s poor, but at the same time, it’s not at all distressing (angoissant).

Parnet: You find it funny? (Ça te fait rire?)

Deleuze: Yes, I find it funny. I tell myself, at my age, this is not the first time that impoverished periods have occurred.[15] I tell myself, what have I lived through since I was old enough to be somewhat enthusiastic? I lived through the Liberation and the aftermath. It was among the richest periods one could imagine, when we were discovering or rediscovering everything… The Liberation… The war had taken place and that was no piece of cake (pas de la tarte)… We were discovering everything, the American novel, Kafka, the domain of research… There was Sartre… You cannot imagine what it was like, I mean intellectually, what we were discovering or rediscovering in painting, etc. One has to understand… There was the huge polemic, “Must we burn Kafka?”[16] It’s unimaginable and seems a bit infantile today, but it was a very stimulating, creative atmosphere.

And I lived through the period before May ’68 that was an extremely rich period all the way to shortly after May ’68. And in the meantime, if there were impoverished periods, that’s quite normal, but it’s not the fact of poverty that I find disturbing, but rather the insolence or impudence of people who inhabit the impoverished periods. They are much more wicked than the inspired people who come to life during rich periods.

Parnet: Inspired or just well-meaning? Because you referred to the Kafka polemic at the time of the Liberation, and there was that Alexander What’s-his-name who was very happy with the fact that he had never read Kafka, and he said it while laughing…

Deleuze: Well, yes, he was very happy… The stupider they are, the happier they are, since… Like those who think, and we come back to this, that literature is now a tiny little private affair… If one thinks that, then there’s no need to read Kafka, no need to read very much, since if one has a pretty little pen, one is naturally Kafka’s equal… There’s no work involved there, no work at all…

I mean, how can I explain myself? Let’s take something more serious on this [subject] than those young fools (jeunes sots). I recently went to the Cosmos to see a film…

Parnet: By Parajanov?

Deleuze: No, it wasn’t Parajanov, although he’s quite admirable. It was a very moving Russian film that was made about thirty years ago, but that has only been released very recently…

Parnet: Le Commissaire ?

Deleuze : Le Commissaire.[17] In this, I found something that was very moving… The film was very, very good, couldn’t have been better… perfect. But we noticed with a kind of terror, or a kind of compassion, that it was a film like the ones the Russians used to make before the war…

Parnet: In the time of Eisenstein…

Deleuze: … in the time of Eisenstein, of Dovzehnko. Everything was there, parallel editing notably, parallel editing that was sublime, etc. It was as if nothing had happened since the war, as if nothing had happened in cinema. And I told myself, it’s inevitable, the film is good, sure, but it was very strange too, for that reason, and if it was not that good, it was for that reason. It was literally by someone who had been so isolated in his work that he created a film the way films were made 20 years ago… It wasn’t all that bad, only that it was quite good, quite amazing for twenty years earlier. Everything that happened in the meantime, he never knew about it, I mean, since he had grown up in a desert. It’s awful… Crossing a desert is nothing much, working in, passing through a desert period is not bad. What is awful is being born in this desert, and growing up in it… That’s frightful, I imagine… One must have an impression of solitude…

Parnet: Like for young people who are 18-years old now, for example?

Deleuze: Right, especially when you understand that when things… This is what happens in impoverished periods. When things disappear, no one notices it for a simple reason: when something disappears, no one misses it. The Stalinian period caused Russian literature to disappear, and the Russians didn’t notice, I mean, the majority of Russians, they just didn’t notice, a literature that had been a turbulent literature throughout the nineteenth century, it just disappeared. I know that now people say there are the dissidents, etc., but on the level of a people, the Russian people, their literature disappeared, their painting disappeared, and nobody noticed.

Today, to account for what is happening today, obviously there are new young people who certainly have genius. Let us suppose, I don’t like the expression, but let us suppose that there are new Becketts, the new Becketts of today…

Parnet: I thought you were going to say the “New Philosophers”!

Deleuze: [chortling] It’s not about them because…[18]

But the new Becketts of today… Let us assume that they don’t get published — after all, Beckett almost did not get published — it’s obvious nothing would be missed. By definition, a great author or a genius is someone who brings forth something new. If this innovation does not appear, then that bothers no one, no one misses it since no one has the slightest idea about it. If Proust… if Kafka had never been published, no one could say that Kafka would be missed… If someone had burned all of Kafka’s writings, no one could say, “Ah, we really miss that!” since no one would have any idea of what had disappeared. If the new Becketts of today are kept from publishing by the current system of publishing, one cannot say, “Oh, we really miss that!”

I heard a declaration, the most impudent declaration I have ever heard — I don’t dare say to whom it was attributed in some newspaper since these kinds of things are never certain – someone in the publishing field who dared to say: “You know, today, we no longer risk making mistakes like Gallimard did when he initially refused to publish Proust since we have the means today…”

Parnet: The headhunters…

Deleuze: [laughing] … You’d think you were dreaming, “but with the means we have today to locate and recognize new Prousts and new Becketts.” That’s like saying they have some sort of Geiger counter and that the new Beckett – that is, someone who is completely unimaginable since [Deleuze laughs] we don’t know what kind of innovation he would bring – he would emit some kind of sound or emit some kind of glow if…

Parnet: … if you passed it over his head…

Deleuze: … if you passed it in his path. So, what defines the crisis today, with all these idiocies (conneries)? The crisis today I attribute to three things — but it will pass, I still remain quite optimistic — this is what defines a desert period: First, that journalists have conquered the book form. Journalists have always written [books], and I find it quite good that journalists write, but when journalists used to undertake a book, they used to believe that they were moving into a different form of writing, not the same thing as writing their newspaper articles.[19]

Parnet: One can recall that for a long time, there were writers who were also journalists… Mallarmé, they could do journalism, but the reverse didn’t occur…

Deleuze: Now, it’s the reverse… The journalist as journalist has conquered the book form, that is, he finds it quite normal to write, just like that, a book that would hardly require a newspaper article. And that’s not good at all.

The second reason is that a generalized idea has spread that anyone can write since writing has become the tiny little affair of the individual, with family archives, either written archives or archives [Deleuze laughs]… in one’s head. Everybody has had a love story, everybody has had a grandmother who was ill, a mother who was dying in awful conditions. They tell themselves, ok, I can write a novel about it. It’s not at all a novel, I mean, really not at all. So…

Parnet: The third reason?

Deleuze: The third reason is that, you understand, the real customers have changed. One realizes… Of course, people are still there, still well informed (au courant), but the customers have changed. I mean, who are the television customers? It’s not the people listening, but rather the announcers, they are the real customers. The listeners want what the announcers want.

Parnet: The television viewers (les téléspectateurs)…

Deleuze: Yes, the television viewers.

[Change of cassette; the producer claps his hand while the director announces: “Gilles Deleuze, seventh cassette”]

Parnet: And the third reason is what?

Deleuze: Like I was saying, the announcers are the real customers, and there is no longer… And I was saying that, in publishing, there is a risk that the real customers of editors are not the potential readers, but rather the distributors. When the distributors become the real customers of the editors, what will happen? What interests distributors is the rapid turnover, which results in mass market products, rapid turnover in the regime of the best seller, etc., which means that all literature, if I dare say it this way, all creative literature in the manner of Beckett (à la Beckett), will be crushed by it, naturally.[20]

Parnet: Well, that exists already, they are pre-formed on the basis of the public’s needs…

Deleuze: Right, which is what defines the period of drought: Bernard Pivot, literature as nullity, the disappearance of all literary criticism outside commercial promotion.[21]

Yet, when I say that it’s not all that serious, it’s obvious that there will always be either parallel circuits or a means of expression for a parallel black market, etc. It’s not possible for us to live… The Russians lost their literature, but they will manage to win it back somehow. All that falls into place, rich periods following impoverished periods. Woe betide the poor! (Malheur aux pauvres!)

Parnet: Woe betide the poor. About this idea of parallel markets or black markets: for a long time [literary] topics have been pre-determined. That is, in a given year, one sees clearly on publication lists that it’s war, in another year, it’s the death of one’s parents, another year, it’s attachment to nature, that sort of thing, but nothing appearing to emerge anew. So, have you seen the resurgence of a rich period after an impoverished one, have you lived through that?

Deleuze: Well, yes, like I already said, [Deleuze appears a bit tired here with the question] after the Liberation, it wasn’t very strong until May ’68 occurred. Between the creative period of the Liberation and… when was the beginning of the “New Wave”, it was 1960?

Parnet: 1960… even earlier…

Deleuze: Between 1960 and 1972, let’s say, there was a new rich period. Certainly! It occurred… It’s a little like Nietzsche said so well, someone launches an arrow into space. That’s what… Or even a period, or a collectivity launches an arrow, and eventually it falls, and then someone comes along to pick it up and hurl it out elsewhere, so that’s how creation happens, how literature happens, passing through desert periods.[22]

“D as in Desire”

Parnet: On that hopeful note, we pass on to “D.” So, for “D,” I need to refer to this page since I am going to read what’s in the Larousse… In the Petit Larousse Illustré [an important French dictionary with biographical references], “Deleuze, Gilles, French philosopher, born in Paris in 1927…” Uh, “1925,” excuse me…

Deleuze: So they’ve put me in the Larousse now, eh? They change things every year, the Larousse…

Parnet: Well, this is [the] 1988 [edition]…

Deleuze: Ah, fine…

Parnet: “With Félix Guattari, they show the importance of desire and its revolutionary aspect confronting all institutions, even psychoanalytic.” For the work demonstrating all this, they cite Anti-Oedipus, 1972. So precisely, since everyone wants you to pass for the philosopher of desire, I want you to talk about desire. What was desire exactly? No doubt the most scintillating question in the world regarding Anti-Oedipus…

Deleuze: It’s not what they thought it was, in any case, not what they thought it was, even back then. Even, I mean, the most charming people who were… It was a big ambiguity, it was a big misunderstanding, or rather a little one, a little misunderstanding. I believe that we wanted to say something very simple. In fact, we had an enormous ambition, notably when one writes a book, we thought that we would say something new, specifically that one way or another, people who wrote before us didn’t understand what desire meant. That is, in undertaking our task as philosophers, we were hoping to propose a new concept of desire. But, regarding concepts, people who don’t do philosophy mustn’t think that they are so abstract… On the contrary, they refer to things that are extremely simple, extremely concrete, we’ll see this later… There are no philosophical concepts that do not refer to non-philosophical coordinates. It’s very simple, very concrete.

What we wanted to express was the simplest thing in the world. We wanted to say: up until now, you speak abstractly about desire because you extract an object that’s presumed to be the object of your desire. So, one could say, I desire a woman, I desire to leave on a trip, I desire this, that. And we were saying something really very simple, simple, simple: You never desire someone or something, you always desire an aggregate (ensemble). It’s not complicated. Our question was: what is the nature of relations between elements in order for there to be desire, for these elements to become desirable? I mean, I don’t desire a woman — I am ashamed to say things like that since Proust already said it, and it’s beautiful in Proust: I don’t desire a woman, I also desire a landscape (paysage) that is enveloped in this woman, a landscape that, if needs be — I don’t know — but that I can feel. As long as I haven’t yet unfolded (déroulé) the landscape that envelops her, I will not be happy, that is, my desire will not have been attained, my desire will remain unsatisfied.

I’m choosing an aggregate with two terms: woman/landscape, and it’s something completely different. If a woman says, “I desire a dress,” or “I desire (some) thing” or “(some) blouse,” it’s obvious that she does not desire this dress or that blouse in the abstract. She desires it in an entire context, a context of her own life that she is going to organize, the desire in relation not only with a landscape, but with people who are her friends, with people who are not her friends, with her profession, etc. I never desire some thing all by itself, I don’t desire an aggregate either, I desire from within an aggregate.

So, we can return to something we were discussing earlier, about alcohol, drinking [“B as in Boire”]. Drinking never meant solely “I desire to drink” and that’s it. It means, either I desire to drink all alone while working, or drink all alone while relaxing, or going out to find friends to have a drink, go to some little café. In other words, there is no desire that does not flow – I mean this precisely — flow within an assemblage (agencement). Such that desire has always been for me – I am looking for the abstract term that corresponds to desire – it has always been constructivism. To desire is to construct an assemblage, to construct an aggregate: the aggregate of a skirt, of a sun ray,

Parnet: … of a woman …

Deleuze: … of a street, an assemblage of a woman, of a vista…

Parnet: … of a color…

Deleuze: …of a color, that’s what desire is: constructing an assemblage, constructing a region, really, to assemble (agencer). Desire is a constructivism. So, I’m saying that we, in Anti-Oedipus, we were trying…

Parnet [interrupting]: Can I…?

Deleuze: Yes?

Parent: Is it because desire is an assemblage that you needed to be two in order to create it? In an aggregate, where Félix was necessary, who emerged then to help write.

Deleuze: Did it… well, perhaps that will be more connected to what we have to discuss about friendship, of the relationship between philosophy and something that concerns friendship… But certainly, with Félix, we created an assemblage, yes…. There are assemblages all alone, I repeat, and then there are assemblages with two people – Félix, everything I did with Félix was a shared assemblage (agencement à deux), in which something passed between both of us. That is, all of this concerns physical phenomena. In order for an event to occur, a difference of potential is necessary, and for there to be a difference of potential, two levels are required, so that something occurs, a flash occurs or a flash doesn’t occur, or a little stream… And that’s in the domain of desire. That’s what a desire is, constructing. Every one of us spends his/her time constructing… When anyone says, every time anyone says, I desire this or that, that means that he/she is in the process of constructing an assemblage, and it’s nothing else, desire is nothing else.[23]

[Change of cassette (cassette 8); the producer claps his hand]

Parnet: So, precisely, is it just by chance that, since desire exists in an aggregate, in an assemblage, that Anti-Oedipus, where you talk about desire, where you start to talk about desire, is the first book you wrote with someone else… that is, with Félix Guattari?

Deleuze: Yes, you are quite right… No doubt, we had to enter into what was a new assemblage for us, to write as two (à deux), that each of us did not interpret or live in the same way, so that something might “pass” (pour que quelque chose passe). And if something “passed,” this was finally a fundamental reaction, hostility against the dominant conceptions of desire, the psychoanalytical conceptions. We had to be two, Félix who had been in psychoanalysis, myself interested in this subject, we needed all that so that we could say we had the possibility here of a constructive, constructivist concept of desire.

Parnet: Can you define better, maybe quickly, simply, how you see the difference between this constructivism and analytical interpretation? … Are there any . . .

Deleuze: It’s quite simple, I think, it’s quite simple, given our position regarding psychoanalysis… There are multiple facets, but in terms of the problem of desire, really psychoanalysts speak of desire exactly like priests talk about it – this is not the only comparison — they are psychoanalyst-priests. And they talk about it under the guise of the great wailing about castration – castration, it’s worse than original sin, castration is… It’s a kind of enormous curse on desire that is quite precisely frightening.

What did we try to do in Anti-Oedipus? I think there are three main points directly opposed to psychoanalysis. These three points are — well, for me and I think for Félix as well, we would change none of these points at all.[24] That’s because we are persuaded that the unconscious is not a theater, not a place where Hamlet and Oedipus interminably play out their scenes. It’s not a theater, but a factory, it’s production… The unconscious produces there, incessantly produces… It functions like a factory, it’s the very opposite of the psychoanalytical vision of the unconscious as a theater where it’s always a question of Hamlet or Oedipus moving about constantly, infinitely…

The second theme is that delirium, which is very closely linked to desire – to desire is to become delirious (délirer) to some extent… If you look at delirium whatever it might be about, any delirium whatsoever, it is exactly the contrary of what psychoanalysis has latched onto about it, that is, we don’t go into delirium about the father or mother. Rather, one “délires” about something completely different; this is the great secret of delirium, we “délire” about the whole world. That is, one “délires” about history, geography, tribes, deserts, peoples . . .

Parnet: Climates…

Deleuze: … races, climates, that’s what we “délire” about. The world of delirium is, “I am an animal, a Negro”, Rimbaud.[25] It’s: where are my tribes, how are my tribes arranged, surviving in the desert, etc.? The desert… uh, delirium is geographical-political; psychoanalysis links it always to familial determinants. Even after so many years since Anti-Oedipus, I maintain that psychoanalysis never understood anything at all about a phenomenon of delirium. One “délires” the world and not one’s little family. And all this intersects: when I referred to literature not being someone’s little private affair, it comes down to the same thing: delirium as well is not a delirium focused on the father and mother.

3) The third point, it returns to desire: desire always established itself, always constructs assemblages there and establishes itself in an assemblage, always putting several factors into play, and psychoanalysis ceaselessly reduces us to a single factor, always the same, sometimes the father, sometimes the mother, sometimes the phallus, etc. It is completely ignorant of what the multiple is, completely ignorant of constructivism, that is, of assemblages.

I’ll give some examples. We were talking about the animal earlier. For psychoanalysis, the animal is the image of the father, let’s say, a horse is the image of the father. It’s a fucking joke (c’est se foutre du monde). I think of the example of Little Hans, a child about whom Freud rendered an opinion… He witnesses a horse falling in the street and the wagon driver who beats the horse with a whip, and the horse is twitching all around, kicking out… Before cars, automobiles, this was a common spectacle in the streets, something quite impressive for a child. The first time a child sees a horse fall in the street and a half-drunk driver trying to revive it by whipping it, that must have caused such an emotion… It was something happening in the street, the event in the street, sometimes a very bloody event. Then you hear the psychoanalysts talking about the image of the father, etc., it’s in their heads that things get confused. That desire might concern a horse fallen and beaten in the street, dying in the street, etc., well that’s an assemblage, a fantastic assemblage for a child, it’s disturbing to the very core.[26]

Another example I could choose, another example: we were talking about the animal. What is an animal? There is no single animal that could be the image of the father. Animals usually group together in a pack, there are packs.[27] There is case that gives me a lot of pleasure, in a text that I adore by Jung, who broke off from Freud after a long collaboration. Jung told Freud that he had a dream about an ossuary, and Freud literally understood nothing.[28] He told Jung constantly, “if you dream about a bone, it means the death of someone.” But Jung never stopped telling him, “I didn’t tell you about a bone, I dreamt about an ossuary.” Freud didn’t get it. He couldn’t distinguish between an ossuary and a bone, that is… An ossuary is one hundred bones, a thousand bones, ten thousand bones… That’s what a multiplicity is, that’s what an assemblage is. I am walking in an ossuary… What does that mean? Where does desire “pass”? In an assemblage, it’s always a collective, a kind of constructivism, etc., that’s what desire is. Where does my desire “pass” among these thousand cracks, these thousand bones? Where does my desire “pass” in the pack? What is my position in the pack? Am I outside the pack, alongside, inside, at the center? All these things are phenomena of desire. That’s what desire is.

Parnet: This collective assemblage precisely… Since Anti-Oedipus is a book that was written in 1972, the collective assemblage came at an appropriate moment after May ‘68, that is, it was a reflection…

Deleuze: Exactly.

Parnet: … of that particular period, and against psychoanalysis that maintained its little affair…?

Deleuze: One can only say: delirium “délires” races and tribes, it “délires” peoples, it “délires” history and geography — all that seems to me to correspond precisely to May ’68. That is, it seems to me, [May ’68 was] an attempt to introduce a little bit of fresh air into the fetid, stifling atmosphere of familial deliriums. People saw quite clearly that this is what delirium was… If I am going to get delirious (délirer), it won’t be about my childhood, about my little private affair. We “délire”… Delirium is cosmic, one “délires” about the ends of the world, about particles, about electrons, not about papa and mama, obviously.

[Change of cassette; the producer claps his hand while the director announces: “Gilles Deleuze, cassette nine”]

Parnet: Well, precisely about this collective assemblage of desire, I recall several misunderstandings… I remember at Vincennes in the 1970s [where Deleuze taught], at the university, there were people who put into practice this “desire” that resulted instead in kinds of collective infatuations (amours collectifs), as if they never really understood very well. [Deleuze smiles] So I would like… Or more precisely, because there were a lot of “crazies” at Vincennes… Since you started from schizoanalysis to fight against psychoanalysis, everybody thought that it was quite fine to be crazy, to be schizo… So we saw some incredible things among the students, and I would like you to tell me some funny stories, or not so funny ones, about these misunderstandings regarding desire.

Deleuze: Well, the misunderstandings… I can perhaps consider the misunderstandings more abstractly. The misunderstandings generally were connected to two points, two cases, which were more or less the same: some people thought that desire was a form of spontaneity, so there were all sorts of movements of “spontaneity”…

Parnet: The “Mao-Spontex”, they’re renowned![29]

Deleuze: … and others thought desire was an occasion for partying (la fête). For us, it was neither one nor the other, but that had little importance since assemblages got created, even the crazies, the crazies, the crazies (les fous) – there were so many, all kinds, they were part of what was happening then at Vincennes. But the crazies, they had their own discipline, their own way of… they made their speeches, they made their interventions, and they also entered into an assemblage, they constructed their own assemblage, and they did very well in the assemblage. There was a kind of guile, comprehension, a general good will of the crazies.

But, if you prefer, on the level of theory, practically … These were assemblages (agencements) that were established and that fell apart. Theoretically, the misunderstanding was to say: Ok, desire is spontaneity, hence the name they were called, the spontaneists; or it’s la fête, and that’s not what it was. The so-called philosophy of desire consisted only in telling people: don’t go get psychoanalyzed, never interpret, go experience/experiment with assemblages, search out the assemblages that suit you, let each person search…

So, what was an assemblage? For me, an assemblage — for Félix, it’s not that he thought something else, but it was perhaps… I don’t know – but for me, I would maintain that there were four components of an assemblage, if you wish… This said very very roughly, so I am not tied to it, maybe there are six…

1) An assemblage referred to “states of things”, so that each of us might find the “state of things” that suits us. For example, earlier, for drinking, I like this café, I don’t like that café, the people that are in a particular café, etc., that’s a “state of things.”

2) Another dimension of assemblages: “les énoncés”, little statements, each person has a kind of style, his/her way of talking. So, it’s between the two things (à cheval). In the café, for example, there are friends, and one has a certain way of talking with one’s friends, so each café has its style – I say the café, but that applies to all kinds of other things.

Ok, so an assemblage encompasses “states of things” and then “statements,” styles of enunciation … Eh… it’s really interesting… History in the space of five years can produce a new kind of statement… For example, in the Russian revolution, when did statements of a Leninist kind appear, how, in what form? In May ’68, when did the first kinds of so-called ’68 statements appear? It’s very complex. In any case, every assemblage implies styles of enunciation.

3) An assemblage implies territories, each of us chooses or creates a territory, even just walking into a room, one chooses a territory. I walk into a room that I don’t know, I look for a territory, that is, the spot where I feel the best in the room.

4) And then there are processes of what one has to call deterritorialization, that is, the way one leaves the territory.

I would say that an assemblage encompasses these four dimensions: states of things, enunciations, territories, movements of deterritorialization. It’s within these [components] that desire flows. So… the crazies…

Parnet: Did you feel particularly responsible for people who took drugs, [Parnet laughs, apparently a bit embarrassed] who might have read Anti-Oedipus a bit too literally? Because, I mean, it was, it’s not a problem, not like someone incites who young people to commit stupid acts (conneries). [Deleuze looks visibly uncomfortable with the subject]

Deleuze [speaking very softly and precisely]: One always feel quite responsible for anyone for whom things went badly (tournait mal)…

Parnet: What were the effects of Anti-Oedipus?