February 24, 1976

Our method — or the method that you accept or pretend to accept, me too — this rhizome method could have as its motto: “I hate memories. Nothing good comes of memories. Memories are actually a knot of arborescence.” But at the same time, how can we speak about the close-up without referring to specific films, which is to say filmic memories? … I would just like to ask you for the next half hour, before going back to our new research topic on the two types of delirium, to forget what wasn’t working. … And if things don’t work out again, it’s no big deal, we can just say that maybe this year it’s too soon to speak about the close-up. We just need a few basic notions of cinema so as not make any howling errors. … And we just need a few memories, just enough to say: “Ah yes in that film, there was something of that nature.” You could go and rewatch it.

Seminar Introduction

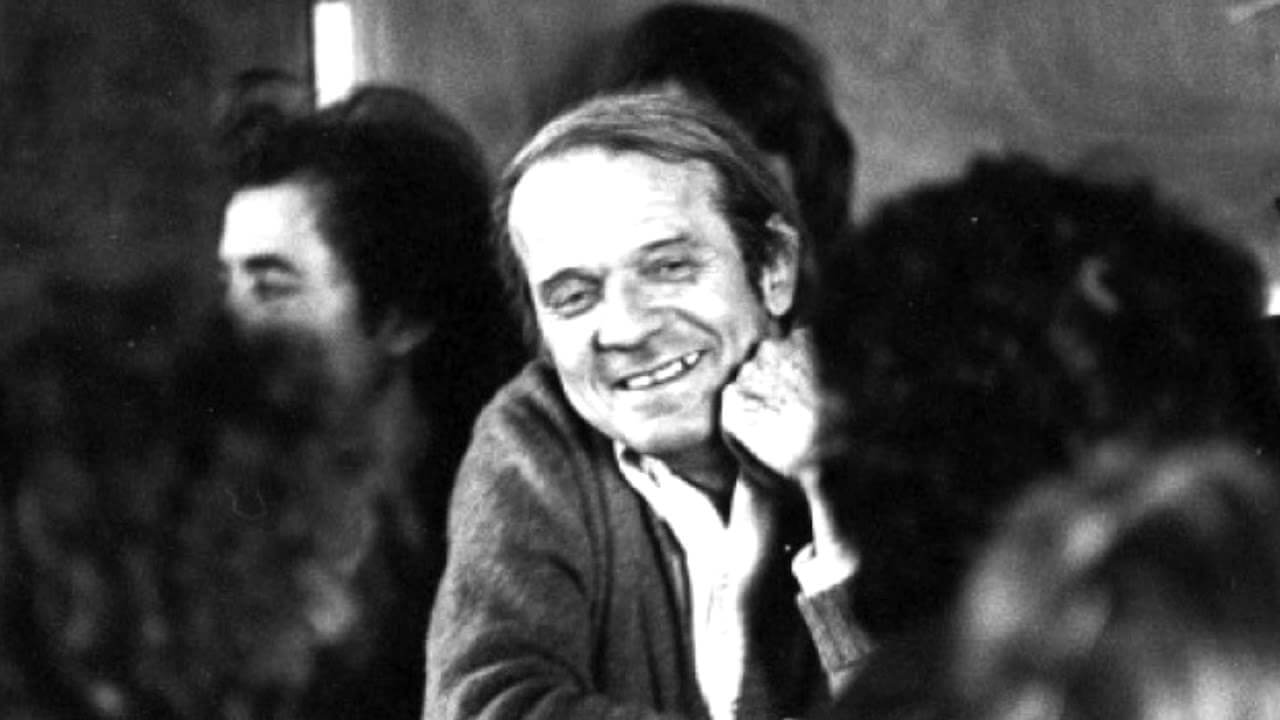

Deleuze’s 1975-1976 seminars were filmed by one of his students, Marielle Burkhalter, as part of her masters project, “Filming Philosophy as it Happens.” Enrico Ghezzi acquired the videos for broadcast on the RAI 3 cinema programme “Fuori Orario,” after inviting Burkhalter to screen them at a festival he co-curated. Marielle Burkhalter, along with Stavroula Bellos, would eventually become the director of the L’association Siècle Deleuzien, and oversaw the French transcriptions of Deleuze’s seminars at the Voix de Gilles Deleuze website at the University of Paris 8.

Links to a number of these recordings that are available on YouTube are provided below, each of which includes subtitles in Italian. We are grateful to those who have uploaded these videos.

We have ordered the video material chronologically and divided it into 3 categories, providing short titles describing the topics covered for general orientation.

The first category (A) refers to the aforementioned seminars that were filmed at Paris-8 Vincennes in 1975-76, while Deleuze and Guattari were working on specific “plateaus” within what would become “Mille Plateaux”. We have clues for approximate dates and one specific indication to help situate these. First, in the session (or sessions) under the Molar and Molecular Multiplicities recording, Deleuze addresses material in A Thousand Plateaus that precedes topics discussed in the subsequent Il Senso in Meno recordings. Then, an Iranian student speaking in session 7 states this session’s date as February 3, 1976. Thus, for the sessions 2 through 6, we have provided approximate dates for successive Tuesdays that follow session 1 and precede February 3, while two sessions, 4 & 5, that occur on the same day, receive the same date. For the sessions following session 7, we have provided approximate dates corresponding to subsequent Tuesdays while 1) making adjustments for a missing session that preceded session 8; and 2) including under March 2 both session 9 (all three segments included in the recording) and session 10.

The second category (B) includes seminars from 1980-87, after the campus of Vincennes had been demolished and relocated to St. Denis. The third category (C) features fragments and short clips from the Il Senso in Meno recordings, which we have ordered sequentially and have also provided time stamps to the transcriptions.

A. Deleuze at Paris 8-Vincennes, 1975-76

See above for our explanation of these three film presentations of Deleuze’s seminar:

deleuze su molteplicità molare e molteplicità molecolare (1:40:51)

Il Senso In Meno 1 Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari Vincennes, 1975 1976 Parti 1 2 3 4 5 [ISM I below] (4:00:00)

Il Senso In Meno 2 Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari Vincennes, 1975 1976 Parti 6 7 8 9 [ISM 2 below] (4:21:40)

B. Deleuze at Paris 8-St.Denis, 1980-87

The personal pronoun “I” (1980) (video link only partial), with transcript and new translation located in the second Anti-Oedipus and Other Reflections Seminar, 3 June 1980: https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x36nts9

Deleuze sur Hegel (1980) follows the preceding clip, with transcript and translation located in the second Anti-Oedipus and Other Reflections Seminar, 3 June 1980.

On Leibniz (1986) — Session 3 (18 Nov 1986), transcript and translation located in the Leibniz and the Baroque seminar, 1986-87: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yEg4Tc40rWM

On Harmony (1987) — Session 20 (2 June 1987), transcript and translation located in the Leibniz and the Baroque seminar, Deleuze’s final session before retirement: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_JBMX6uECxc

C. Various clips that are segments from the longer videos included above in A, Il Senso in Meno I and II, abbreviated below respectively ISM I and ISM II; the second time mark provided corresponds to the short alternate segments taken from ISM I located on YouTube as “Deleuze et Guattari a Vincennes” and under the French transcript link for each session:

Gilles Deleuze, Pierre-Félix Guattari a Vincennes (1975-1976) (22:30) — A brief clip near the start of ISM I, ATP I.2 (time stamp: 34:00-57:00/ 27:00-50:00)

Félix Guattari – Université de Vincennes 1975 (9:56) — The opening (in progress) of the first session in ISM I, ATP I.2 (time stamp: 7:00-16:56/ 0:00-9:56)

Deleuze sur le langage (1:19) — Very brief segment drawn from the first part of ISM I, ATP I.2 (time stamp: 39:00-41:00/32:00-34:00)

Deleuze sur la musique (1:04) — Very brief segment drawn from the first part of ISM I, ATP I.2 (time stamp 56:20-57:24/49:24-50:28)

Deleuze et le roman (9:35) — Segment drawn from the beginning of the fourth part of ISM I, ATP I.5 (time stamp: 8:00-17:34/1:00-10:34)

Deleuze – Boulez – Berg (5:36) — A stand-alone segment NOT drawn from Deleuze’s seminar and undated, seemingly filmed at his home with friends listening. No transcript or translation is currently available.

Gilles Deleuze – Morale ed etica (Lezioni a Vincennes, 1975/76) — A separate brief interview with Richard Pinhas (7:03). No transcript or translation is currently available.

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 1 (sub. ITA) (9:47) — First of 15 successive segments drawn from ISM I, ATP I.2 (time stamp: 23:24-33:06/16:25-26:03)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 2 (sub. ITA) (9:51) — Second of 15 successive segments drawn from ISM I, ATP I.2 (time stamp: 33:07-42:53/26:04-35:59)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 3 (sub. ITA) (4:36) — Third of 15 successive segments drawn from ISM I, ATP I.2 (time stamp: 42:50- 47:17/ 35:50- 40:23)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 4 (sub. ITA) (9:27) — Fourth of 15 successive segments drawn from ISM I, ATP I.2 (time stamp: 47:05-56:15/40:15-49:30)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 5 (sub. ITA) (9:56) — Fifth of 15 successive segments drawn from ISM I, end of ATP I.2 & start of ATP I.3 (time stamp: ISM I 56:20-1:06:10/ATP I.2 49:25-58:03 & ATP I.3 0:00-1:09)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 6 (sub. ITA) (9:50) — Sixth of 15 successive segments drawn from ISM I, ATP I.3 (time stamp: 1:06:11-1:16:00/1:10- 11:00)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 7 (sub. ITA) (9:47) — Seventh of 15 successive segments drawn from ISM I, ATP I.3 (time stamp: 1:16:01- 1:25:49/11:01-20:55)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 8 (sub. ITA) (9:49) — Eighth of 15 successive segments drawn from ISM I, ATP I.3 (time stamp: 1:25:48-1:35:35/20:54-30:30)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 9 (sub. ITA) (9:58) — Ninth of 15 successive segments from ISM I, end of ATP 1.3 & start of ATP I.4 (time stamp: ISM I 1:35:32-1:45:12/ATP I.3 30:27-37:01 & ATP I.4 0:00-3:20)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 10 (sub. ITA) (9:48) — Tenth of 15 successive segments from ISM I, ATP I.4 (time stamp: 1:45-23-1:55:05/ 3.26-13:01)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 11 (sub. ITA) (9:52) — Eleventh of 15 successive segments from ISM I, ATP I.4 (time stamp: 1:54:46-2:04:37/ 12:40-22:)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 12 (sub. ITA) (9:35) — Twelfth of 15 successive segments from ISM I, ATP I.4 (time stamp: 2:04:37-2:14:07/ 22:30-32:05)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 13 (sub. ITA) (9:52) — Thirteenth of 15 successive segments from ISM I, ATP I.4 (time stamp: 2:14:03-2:23:53/ 32:00-41:50)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 14 (sub. ITA) (9:54) — Fourteenth of 15 successive segments from ISM I, ATP I.4 (time stamp: 2:23:50-2:33 38/ 41:46-51:38)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes, 15 (sub. ITA) (9:56) — Fifteenth of 15 successive segments from ISM I, end of ATP I.4 & start of ATP I.5 (time stamp: 2:33:31-2:43:23/ATP I.4 51:30-56:33 & ATP I.5 0:00-4:35)

Gilles Deleuze, Lecture, Mille Plateaux 1 (7:00) — First of two successive segments drawn from part 3 of ISM II, the opening seven minutes of ATP I.9 (time stamp 2:23:29-2:29:00)

Gilles Deleuze, Lecture, Mille Plateaux 2 (9:26) — Second of two successive segments drawn from part 3 of ISM II, the next almost ten minutes of ATP I.9 (time stamp: 2:29:00-2:38:26)

Gilles Deleuze – Vincennes 1975-76 (compilation) — A long segment, almost the entirety of ISM II, beginning at 1:13:55, with the student debate in the middle of ATP I.8, and then including ATP I.9 & 10. Although this particular clip seems to begin at 1:28:40, the viewer can back up to the start point. (3:05:57)

Gilles Deleuze à Vincennes 1975 (9) italian sub (51:51) — Segment drawn from the last half of ATP I.9, including the 36-minute debate about expelling from the session a student who apparently accused Deleuze of plagiarism — in ISM 2 (time stamp: 2:53:55-3:45:46)

English Translation

Before closing the “chapter of faciality” as well as discussing two types of delirium, Deleuze proposes that they address the close-up, the purpose being to apply to it the “rhizome method” more systematically. Referring to Josef von Sternberg’s memoirs, Deleuze develops several general propositions about the close-up, and then he compares the pair of effects, lightening or resorting to shadows – to the white wall-black hole system. As for close-ups of things other than the face, Deleuze asserts (with reference to Eisenstein on D.W. Griffith’s cinema) that such close-ups occur provided that the thing in question is caught up in a process of facialization. Deleuze then undertakes to define the close-up by considering different cinematographic means, e.g., a mobile camera approaching a character or object, or a reverse process, close-up as a scale of intensity, and with various references, Deleuze joins the two functions of the close-up to two types of faciality, the despotic face and the passional face, but also notes mixed uses of types of close-ups. At this point, following a recording interruption, a 37-minute debate ensues among the participants regarding the unacceptably crowded conditions in the classroom. A notable moment is Deleuze’s concise argument favoring the smaller, more crowded space (for greater possibilities of student exchange) over the available amphitheater space (entailing greater distance from the students and less opportunity for exchanges). Deleuze attempts to bring discussion to a close by mediating between the opposing sides, mainly to remove the space-wasting tables henceforth, but also to remain in the current space, but at one point, he seems ready to abandon the session, noting how badly things are going, and he also admits to feeling ill. Finally, with no agreement reached besides Deleuze’s proposal, the session continues for another 30 minutes, with Deleuze considering two forms of delirium, specifically paranoid delusions (or delusions of interpretation) and passional delusions (or grievance delusions). He fleshes out these distinctions with numerous references, modern, classical and biblical, and he concludes the session by proposing that they continue to examine the two systems, the one irradiating, despotic, frontal faced, based on trickery and deceit; the other linear, passional, diverted faces, based on betrayal.

Gilles Deleuze

Deleuze & Guattari at Vincennes, 1975-76

Il Senso in Meno, Part 7 – The Close-up in Cinema, The Conditions of Study, Two Forms of Delirium

Translated by Graeme Thomson and Silvia Maglioni; revised translation, Charles J. Stivale

[Please note that the transcription follows as exactly as possible the discussion in the filmed seminar, and therefore the translation differs at time with the discussion rendered in the subtitles on the YouTube versions. We should also note that according to Deleuze at the start, the topic of the previous discussion, the close-up, needs to be reviewed and revised; however, as Deleuze mentions below, the discussion occurred between him and several students after the session, hence we have no access to the details]

[29:16, start; 2:23:06, end of YouTube recording, total length, 1:53:50; see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h1Po2tIgeD4]

Deleuze: We’ve now begun a fourth grouping of research. But we’re going to suspend it for the moment, though not for long, not for the entire lesson… I’d like to suspend it because something didn’t work last time, so we need to do a collective auto-critique – personal auto-critique is a bad idea but collective auto-critique can be useful. We all agreed that it was just about time to close the chapter of faciality, that we had spoken enough about the matter. But perhaps we should be able to get something more out of the close-up in cinema.

And then I had the feeling – that I imagine many of you shared – that while many interesting things were said, we had failed to get anywhere. Something wasn’t right. And it was just as well to go on because things might have become clear all of a sudden, though it was by no means certain… I’m sure I’m not the only one but I had the feeling that something wasn’t working. And I asked myself why that was. How come we didn’t manage to get anything out of the close-up? Seeing as how that was the case… even if we were well placed… what I mean to say is that what we have to be wary of, always and in every field, are specialists.

Specialists are a really horrible thing, because they know so much, they know too much, and they’re so caught up in problems already coded in function of their speciality that, if you pose a question to a specialist, you’ll discover to your astonishment that there’s absolutely no chance of them giving you an answer. We could have asked someone from the cinema department, or else a critic. But in my view, it was better to avoid doing so. However, we were well placed to do something, whatever that might have been.

So why didn’t it work last time? I think that it’s because, even if it was interesting, what many of us said was linked to some kind of reminiscence: “Ah, I remember, I remember…” – and in a certain sense those memories weren’t completely out of place – “I remember there was a close-up…” It’s interesting, because I said to myself afterwards, our method – or the method that you accept or pretend to accept, me too – this rhizome method could have as its motto: “I hate memories. Nothing good comes of memories. Memories are actually a knot of arborescence.” But at the same time, how can we speak about the close-up without referring to specific films, which is to say filmic memories?

Nonetheless, I think that we failed somehow, because we got stuck in an exchange of memories, like old fools. So, we weren’t being specialists – which was a good thing – but we replaced specialism with a conversation of the type: “Ah yes, that film…” At the same time, of course, we have to cite particular films if we want to talk about the close-up.

I don’t know… I would just like to ask you for the next half hour, before going back to our new research topic on the two types of delirium, to forget what wasn’t working. Although at the same time I found everything you said quite interesting. But as I said, something didn’t work. In exchange, I would like it if somebody, maybe in a week or a fortnight’s time, told me that I got it completely wrong… I’ll just say, on behalf of us all, that we screwed up a bit, not much, nothing serious. We could very well say that, even if the situation were different, we would have screwed up anyway, or that maybe our ideas will be clearer next year. Anyway, let’s try something.

What I propose we do is almost… I have some topics… but I’m not at all sure… and then I would like you to react and propose things yourselves. And then we’ll stop there. And if things don’t work out again, it’s no big deal, we can just say that maybe this year it’s too soon to speak about the close-up.

We just need a few basic notions of cinema so as not make any howling errors. It’s not my case, of course. But perhaps there are some here who don’t know anything. And we just need a few memories, just enough to say: “Ah yes in that film, there was something of that nature.” You could go and rewatch it. Yes, but in any case… So here is my first proposal. And sorry if I seem… no forget it, I don’t need to apologize.

First proposal: as a theorem, a general proposition regarding the close-up as I found it… because I was so unhappy… though I liked some things that were said… I wasn’t happy with the way we failed to really get anywhere. So I did some research. And I’m sure that you know this great director, who boasted about having literally created Marlene Dietrich from nothing, and perhaps worse than nothing – and it’s with great bitterness that he says that – this director called Josef Von Sternberg.

Josef Von Sternberg published a memoir, which is translated in French as Souvenirs d’un montreur d’ombres (Fun in a Chinese Laundry) with Laffont. [Pause] [Deleuze returns to von Sternberg’s cinema in Cinema seminar 1, notably sessions 8, 9 and 15, winter/spring 1982; he refers to this Sternberg text in Cinema I: The Movement-Image, p. 231, note 10]

And here we are, in this book, I found a lovely passage that seems to me perfect for our purposes. Because considering where we are, and all that we have said so far about the face, this text completely confirms our theory of the machine of faciality to the point that we could say: “We can take it as our general proposition regarding the close-up.”

And I quote, it’s page 342-343… “The camera has been used to explore the human figure and to concentrate upon its face as being its most precious essence.” This works for us, there’s no need to comment on it. We have tried to say the same thing using other terms. We wouldn’t have said “its most precious essence” but that’s okay.

“Monstrously enlarged as it is on the screen, the human face should be treated like a landscape.” It’s getting better and better! So, for Sternberg, the close-up contains not only what appeared to us to be a fundamental correlation – the correlation face-landscape – without which there wouldn’t be a close-up, exactly in the sense that we developed it previously. But also, the close-up consists in the very treatment of the face as a landscape. If you want to treat a face like a landscape – Sternberg seems to be saying here – you can only do it by using the close-up in cinema.

“… the human face should be treated like a landscape, as if the eyes were lakes, the nose a hill, the cheeks broad meadows, the mouth a flower patch” — he’s obviously thinking about Marlene — “the forehead sky, and the hair clouds. Values must be altered as in an actual landscape by investing it with lights and shadows, controlled with gauze and graded filters and by domination of all that surrounds the face. Just as I spray trees with aluminum to give life to the absorbent green, just as the sky is filtered to graduate its glare, just as the camera is pointed to catch a reflection on the surface of a lake, even so the face and its framing values must be viewed objectively as if it were an inanimate surface. The skin should reflect and not blot the lights, and light must be used to caress, not flatten and wipe out that which it strikes.”

“The skin should reflect…” So what Sternberg is telling us is that the close-up’s function is to treat the face like a landscape in conditions in which the surface of the face reflects the light. So, there we have the first major characteristic of the close-up. There are already so many observations we could make at this point, but let’s stifle them for the moment and try to put things in order.

He continues and here the text gets a bit bizarre: “If it is impossible to otherwise improve the quality of the face…” — here he’s speaking about the second aspect of the close-up, as a kind of alternative – if it’s impossible to do what he was talking about before, that is to say, transform the face into a landscape that is able to reflect the light, we see that he has a preference: he prefers the first aspect, but says that there is a second aspect, and I don’t see why other filmmakers might not prefer this… He says that if you can’t manage to attain the first solution, there are other approaches you can take… — Is there a dog here? I heard a dog? First of all, I hate dogs and secondly, I’m afraid of them. Is there really a dog? At least it’s better than a cat, that’s all I can say… —

“If it is impossible to otherwise improve the quality of the face, deep shadows must add intelligence to the eyes, and should that not be enough then it is best to shroud the countenance in merciful darkness and have it take its place as an active pattern in the photographic scale. Before I allow light to strike a face, I light its background to fill the frame with light values, for included in its photographic impact is everything that is visible in the same frame. This principle of containing all values within a frame of values applies also to the human body and its movement through space is to be as a dramatic encounter with light. But whether face, body, a letter, a toy balloon or street, the problem is always the same: lifeless surfaces must be made responsive to light and over-brilliant and flaring surfaces reduced to order…”

You see the two aspects? Make light reflect through the face-landscape, or else if the surfaces are over-brilliant, attenuate and, if need be, darken it. Okay… If we decide to select this as our main proposition regarding the close-up, it’s obviously because it works for us. Here we find fully, [Pause] the close-up either makes the face reflect the light or else resorts to deep shadows, up to and including “merciful darkness.” So that suits us, since we find our white wall-black hole system. And if we might dare to correct Sternberg’s text, we could say that choosing the first aspect over the second is merely his own technical preference. We must recognize that there are also many directors who privilege the second aspect.

So, I ask myself, couldn’t we say the following… making some rapid comparisons? The screen is for sure, a white wall. The camera is for sure a black hole. So, couldn’t we say that there is a close-up when… – and here I’m moving towards a more abstract definition, but maybe it’s stupid, I don’t know – when the face tends to merge with the whole or part of the screen — which leads us to suppose that there are also partial close-ups that don’t occupy the entire screen; I’m pretty sure of this, but I don’t know, we’ll see… — when the face tends to merge with the whole or part of the screen considered as a white wall? So, it’s the face itself that functions as a white wall and is therefore identified with the whole or part of the screen. And similarly, when the face on the screen tends to be identified with or to function as the black hole of the camera. So here we have a first very general proposition regarding the close-up based on Sternberg’s meticulously precise text.

Second proposition: summing up quickly, I’d like to say that there are close-ups of things other than the face. In what conditions? We already have the answer, but we can verify it in the case of cinema since for the moment we’ve only considered faciality at a very general level. Naturally, we can have close-ups of all kinds of things. Though perhaps not everything… perhaps not just any old thing.

We can have close-ups of all kinds of things on the condition that the thing in question is caught up in a process of facialization. And this is the reason cinema is a modern art form and that the power of cinema requires the production of faciality, even if this faciality is abstract. I’m not saying that its production of faciality condemns cinema to a kind of realism or representation. We have already seen how facialization goes far beyond actual faces. However, in order for there to be a close-up on something other than the face, that thing has to undergo a process of facialization.

And regarding this point I’ve been given a very nice text by Eisenstein, where he says, again in relation to Griffith of whom we’ve already spoken a little… Eisenstein’s text begins like this, speaking about Griffith’s close-ups [Deleuze cites this Eisenstein text in The Movement-Image, p. 91; this development on the close-up corresponds to chapter 6, “The Affection Image, Face and Close-up”]:

“The kettle began it . . . Thus Dickens opens his Cricket on the Hearth. The kettle began it…” So immediately there are new aspects to the question that emerge, when Dickens writes at the beginning of ‘The Cricket on the Hearth’… “The kettle began it.” Is he making a close-up here? Which leads us to ask: are there equivalents to the close-up before the cinema? Can we speak of an equivalent to the close-up in painting? Or in writing? And Eisenstein employs Dickens to comment upon all of Griffith’s close-ups.

And he says: “What could be further from films! Trains, cowboys, chases… and ‘The Cricket on the Hearth’? The kettle began it! But, strange as it may seem, movies also were boiling in that kettle. From here, from Dickens, from the Victorian novel, stem the “first shoots of American film aesthetic, forever linked with the name of Griffith.”

Here we would already have some guidelines, if we could show that in fact the novel typically performs processes of facialization that concern use objects, which in a certain sense it contains like a precursor to the cinema close-up – if it’s true that the close-up either concerns faciality or produces facialization. The close-up could be of a knife. We’ll see… or of a kettle. Provided that in a certain sense the kettle looks at me. There, the kettle is looking at me, not in the grotesque sense of having two eyes, or maybe also in this sense, why not – the black hole of the kettle spout. Not surprisingly, Griffith’s interiors always look at me. They look at me in the sense that I’m caught up in these interiors, they regard me. Even if it’s not my kettle, it’s someone’s kettle. At the same time, we can ask ourselves if there are things that resist the process of facialization. And here too our theory will be confirmed. We can say that something that resists the process of facialization cannot be the object of a close-up.

So, the last time we weren’t too happy with what we did regarding the close-up. And it’s by no means certain that we’ll be any happier today, it might not go any better. At the end of the lesson, a number of you stayed behind, and Mathieu Carrière told us about a text he remembered by André Bazin on animals, that now becomes very interesting for us. [In A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari twice refer briefly, without reference, to “an unpublished study of Kleist by Mathieu Carrière” (p. 542, note 50; p. 553, note 11), regarding becoming-animal in Kleist] It ‘s a text where Bazin explains how we cannot make a close-up of an animal. But there’s a problem with the text. Carrière lent me the book which I read but I didn’t see the same thing he saw in it. I don’t think Bazin said anything of the sort… and in a way I’m happy. Although it seemed like a nice idea, it’s even better if it’s not in the book. Or at least I didn’t find it. But let’s suppose he says that: We can’t make close-ups of animals. What does that mean? You’ll tell me, yes there are, there are plenty.

The answer we gave the other time at the end of the lesson was this: that if you make a close-up of an animal in cinema it’s a way of suppressing the animal, of facializing it, of attributing certain things to it and therefore introducing a dimension of anthropomorphism. We often see a big lion’s head. But the great animal films don’t include, or include very few, close-ups. Which doesn’t mean that there aren’t worse techniques. What normally replaces the close-up for animals, for example, is the use of slow motion. In Rossif’s last film there is a terrible use of slow motion in which the animal is no less destroyed than it would be by close-ups. It’s unbearable. The use of slow-motion applied to animals might work a little, but overusing it, that’s ridiculous.

So why would it be useful for us to say. “Okay… no close-ups of animals, it’s not possible.” As we have seen, the animal is defined by a certain state – which by no means implies that it lacks spirituality, however its spirituality involves a system where the head is strictly part of the body and therefore is not organized through a face that overcodes the body. On the contrary, the head is part of an entire corporeal code. So, there can’t be any close-up of the animal if it’s true that the close-up is either faciality or process of facialization. That suits us. But we would also need to demonstrate that each time we have a close-up of an object, as in the case of Griffith’s kettle, there is facialization.

Third problem: The way to obtain – and here we might finally need a specialist who is able to tell us… no, it’s out of the question! – I ask, would it be inconvenient, and here I’m asking a question… would it be inconvenient to say that, as far as we’re concerned, we use the word close-up in a very general sense to account for effects that are produced by very different means? Because in the discussion that followed the last lesson, there was something that disturbed me. Among those who stayed behind, there were some who, if I’ve understood correctly, went as far as to suggest that the close-up doesn’t require or doesn’t necessarily require enlargement, that one could conceive of something that functioned as a close-up without any relative enlargement. I didn’t fully understand this… and then we stopped there.

So, as a way to orient ourselves a bit more clearly, might we not propose certain means, understanding that someone more competent in the matter might tell us: “no, this isn’t what we call a close-up”? All we know for the moment is that the close-up doesn’t necessarily imply immobility. A close-up can perfectly well be part of a tracking shot. Nor it does imply occupying the whole of the screen. For example, a face in close-up might occupy only one side of the screen. But doesn’t it imply a relative enlargement with respect to the other elements in the shot? I would say: yes, it does, but this is obviously just a question of means, it doesn’t help us to define its function. But I recall some of you saying that it doesn’t necessarily imply enlargement.

Let’s try to imagine some different means. The first, the most famous, for which the word close-up is normally reserved refers to a mobile camera approaching a character or object. Another means is the reverse procedure. And the reverse procedure is, I think, frequently employed by the expressionists…. [Tape interrupted] [1:00:18]

The close-up considered as a scale of intensity has a completely different function. It implies introducing in the two-dimensional space of the screen something which is not reducible to two dimensions but which in this case is no longer time but intensity. Basically speaking, this allows us to say that the close-up has nothing to do with either depth of field or perspective. The question of how to add a third dimension to the two dimensions is a completely different one. The same goes for painting: if we find close-ups in painting, they shouldn’t be confused with problems of perspective. Otherwise, we’ll get everything mixed up.

And Eisenstein talks about his own intensive close-ups. Except that there’s something bizarre – I don’t know if it’s the English translation or the political constraints to which Eisenstein was subjected — Eisenstein says: my intensive close-up is a signifying close-up, it’s a close-up that has a meaning whereas Griffith’s close-ups are purely descriptive. It’s funny the way Eisenstein defends himself, as though he were talking to Stalin or Zhdanov, when he says: “I haven’t forgotten, I’m not simply showing things, I mean something by them, I haven’t forgotten the imperatives of the Party!”, whereas in actual fact one would have to say the opposite. If there’s a signifying close-up it’s that of Griffith, in its anticipatory values, whereas the close-up as scale of intensity is absolutely non-signifying, a-signifying.

And Eisenstein proposes examples from his own films such as The Battleship Potemkin, where there is what he himself calls “the line of mounting despair” which passes through several faces. You see this has nothing to do with anticipation, it’s very different… The mounting suffering or rage that passes through numerous faces, whether simultaneous or successive, creates a scale of intensity on the screen but we have no idea what it concerns. It doesn’t signal something which is about to happen. Here the process of mounting intensity is completely immanent. Are soldiers going to appear who will fire into the crowd? Or will something else happen? It’s very different from the knife close-up [Pause; here Deleuze slips implicitly toward the example of Pabst’s Lulu] in which the close-up’s function is to anticipate what will happen. At this point we know that Lulu will die, she’ll die, and that nothing will prevent it. In the intensive close-up, there is a sort of interiorization of the intensive scale that leaves what is going to happen off-screen.

So, were we to accept these two functions of the close-up, I’m saying that would be fine for me; were there only these two, that would suit me fine because they would respond perfectly to our two types of faciality as we have distinguished them: the despotic face and the passional face. So that would work well. The passional face is essentially caught up in an intensive scale while the despotic face is anticipatory. On the despotic face I read my destiny: “I’m going to die.”

But let’s imagine that between these two functions of the close-up there are multiple combinations. And on that point, I’d like to conclude with a quotation from Lotte Eisner, who speaks about an extraordinary scene that unfortunately I have no memory of. I saw it just once in my life, as usual at midnight at the Cinematheque. It’s in Pabst’s film, Lulu. And you will immediately see how useful Eisner’s expressions are useful for us.

“Many times, Pabst films Lulu’s features on a slant. Her face is so voluptuous that it seems almost deprived of individuality…” This works well for us. We’ve seen how individualization is an extremely secondary function of the face. It’s a distant consequence of facialization and faciality. And here I skipped a phrase because it didn’t really fit our needs. In fact, here she got it wrong, it’s obvious… To be honest what she actually writes is “Her face is so voluptuously animal.” What a clanger. This is false. Lulu is not… it’s completely stupid. Well, everyone makes mistakes… Especially as the next part shows that she’s not at all an animal.

In the scene with Jack, she’s inhuman which is completely different from being an animal: “In the scene with Jack the Ripper, this face, a smooth mirror-like disc slanting across the screen” – that’s much better… – “a smooth mirror-like disc slanting across the screen” – like a disc collapsed on the diagonal – “is shaded out…” – remember, that’s Sternberg’s second method – “the shining surface is toned down…” — that’s exactly the second type of close-up Sternberg describes – “that the camera seems to be looking down at some lunar landscape of which it discovers and in a way explains the curves.”

And here I’m skipping another phrase where she gets it wrong: “Pabst just shows, at the edge of the screen…” — if I understand correctly, this is the edge of the screen following the slant. And what we have here is a partial close-up that doesn’t occupy the whole of the screen. So, he shows this lunar landscape from awry. — “Pabst just shows at the edge of the screen the chin and a fragment of cheek belonging…” — Oh, no, it was me who was wrong there, he’s on the other side of the screen — “belonging to the man next to her” – Jack the Ripper – and then she says: “with whom the audience automatically identifies.” Here she makes a personal and rather forced observation, employing an abject concept of “identification”, which is completely pointless… [Tape interrupted] [1:08:22]

So, we have everything we need. There are the two functions of the close-up. The anticipatory close-up: the knife. And the intensive close-up: the face of Lulu consumed, aged, falling apart, and Jack the Ripper walking towards her with what is in this case a reverse close-up of Jack the Ripper’s face which traverses a scale of intensity. Everything happens as though Lulu is the zero intensity. The zero intensity is the matrix. It’s negative, it’s not nothing. The zero intensity is the pure white wall. And with the black silhouette or the reverse close-up of Jack the Ripper’s face; there you have the other function of the close-up. The close-up as intensive scale is no longer the element of anticipation. What’s more, you have the two modalities of the close-up that respond more or less to Sternberg’s text. Which is to say: one in treating Lulu’s face as a landscape, which means making it reflect the light. Or contrariwise, attenuating over-brilliant surfaces by plunging them into merciful darkness. So, in this sense everything is here.

To conclude, here is the last proposition, which I’ve already mentioned: we would need to see to what extent the other arts have their own equivalents to the close-up. This would allow us to objectively define these equivalents in terms of both anticipatory-temporal and intensive values. In a text… And in my view, well why… we’d have to do some research, we’d perhaps have need to consider – I’m again speaking at random once again – both the novel and painting. You shouldn’t be surprised at my saying this. I’m regrouping some notions here. In all we have said so far regarding faciality and facialization, we have seen that painting had a fundamental role in its use of face-landscape complementarity and correlation. And that the courtly novel had a no less fundamental role in the white wall-black hole system of the face-landscape.

So perhaps we could… I don’t know whether I’ve already mentioned this but I’m going to go back to it. I’m thinking about some relatively modern painters. Irrespective of problems of perspective, which are of a completely different nature, I have the impression that often in what we call… when we have a still life that doesn’t occupy the whole of the canvas, but which intervenes in the painting, very often it is oddly facialized. We are at the level of the kettle that looks at me.

There’s a painter I really admire, Bonnard… If you look at Bonnard’s paintings, you’ll see that many of them are of his wife. There are many Bonnard paintings depicting his wife having breakfast. Bonnard’s cups are something extraordinary. There is a kind of facialization of the cup. And once again, everyone will grant me – here I feel a bit guilty — we’ve never used facialization in the sense of anthropomorphism. That doesn’t consist in attributing a human head to the cup. Facialization is an abstract function. Just as there is an abstract machine of faciality. Facialization doesn’t consist in transforming the cup into a man or woman but in making a white wall-black hole system. Or you even have dogs in Bonnard’s paintings, or cats, which are facialized in a quite bizarre way, and without a trace of anthropomorphism. I’m pretty sure of it. Or as Eisenstein wrote, we should take the example of Dickens, which is quite exemplary in literature. [Tape interrupted] [1:13:56]

[After the interruption, a discussion in progress unfolds, concerning issues of classroom space in Deleuze’s seminar]

A first student: If we ‘re going to go on working like this, fine, but I’m leaving, and I won’t concern myself with why… [Inaudible comment] [As this unnamed “first student” will lead most of the discussion, he will be designated as such below]

Second student: It’s been 6 months! What do you want us to do? It’s been like this for 6 months!

The first student: I’ve made some concrete proposals!

Second student: [Indistinct comment] … Wait! Will you let me speak?

Third student: It’s more like three years that’s it’s been this way.

Several students: [Indistinct comments]

The first student: You’re wasting your time. It would take only a couple of minutes to sort it out. [Deleuze is visible quietly listening] Well, my problem is for him to move his ass!

Several students: [Indistinct comments]

Mathieu: If we remove the tables, 50 more people will come in and we’ll be back where we started.

The first student: Well precisely, that will create a problem, but maybe we might organize the space better than me, and at least 50 people have already left.

Deleuze: Please, allow me to respond in my turn. I’m not in any hurry, but … [Pause]

A student: This isn’t a criticism, eh? [Pause]

Deleuze: Yes, I think everyone has something to say, but we’ve already discussed it a lot, but you’re right to come back to this and to raise the question again, but we have spoken a lot about it. [Pause] So, if no one… [Pause] he’s right about one thing. The whole class has something to say, I too would like to say something…

Third student: But what cannot be denied is that most days this room is almost empty! There isn’t even a table normally. There are dozens of chairs stacked up. There really are some and in such a way that… [Indistinct comment]

A student: You think you’re in South America? [Deleuze laughs]

Third student: It’s true, that’s how it is… In that regard, we could at least organize it a bit better.

Several students: [Indistinct comments]

Another student: But the more places there are, the more people there will be!

Another student: Yes, but that’s not a good reason.

Another student: Instead of going on about it, why don’t we turn the seats around? [Indistinct words] Then you can see!

The first student: Now I’ll play like [unclear word] seeing as you were talking about cinema. Your idea is completely stupid. [The student stand on a table and begins crossing the room going from one table to another] These are our working conditions. [Applause from some students] It really is cinema, it’s playing at [same unclear word] …

Another student: Why are you getting so worked up about it?

The first student: It’s three minutes I’ve been trying to get in here.

Another student: Me too!

The first student: Hey, you guys there in the corner, aren’t you getting worked up about it? [Pause] Hey, I don’t want a chair.

Another student: If a fire breaks out… [Indistinct comments]

The first student: If a fire breaks out, I’m dead. [Explosion of laughter and comments making fun of the student’s comment, general brouhaha; the first student begins walking back across the classroom on tables] What I did there at least is without risks. All of you would rush for the doors.

Another student: That’s not true. There’s also a window where I’d go. I’d prefer to break a leg!

Deleuze: I’d die the first!

The first student: You’re right!

Another student: I know someone who has a different solution altogether. He doesn’t want to say it, over there, but he knows that by passing through the window, he can reach you over there.

Another student: Not anymore; it’s closed. Even today we couldn’t manage. The room’s full. The room’s full. [Pause] This has already occurred twice this semester. [Pause]

The first student: Instead of wasting our time arguing, we really could just push all the tables against the wall. There are three walls, three sides, which equate to as many as 100 places!

Another student: So that’s where we’ll really die! [General brouhaha]

The first student: So, what we have is exclusion, selection… Anyone who’s late can’t get in. In these conditions if there are 200 or even 3000 guys who want to get in, we’ll have to queue up like at the Opera, like the theatre. We come here at 7h30, and whoever isn’t here by 7h45 doesn’t get in. And if you don’t see Deleuze, he won’t get in himself because he’ll be stuck in the crowd. [Laughter]

Deleuze: That’s my dream… [Pause, laughter] I just want to say something, because it’s my turn, to respond to you, my point of view independent of the room, seeing as how you’ve raised a question we’ve already discussed many times. In any case, there is something which I would say he’s absolutely right about: the tables crept back in very recently. Before, there weren’t any. Now we’ll move on to other questions but it’s true that these tables occupy a lot of space… It’s not normal for the conditions we have in this room that there are tables. Up until this week, you permitted me a small table because I need books, but it was really tiny. All those tables and this big one were not here… I think that the first to arrive at the lesson should be so kind as to remove the tables, if there are any. More generally…

A student: But we need to keep two, one for the tape recorders.

Deleuze: Yes, of course. But more in general, the problem of this room has already been presented. I’ve already said I don’t want a lecture theatre. And not at all for the reasons that you impute to me, meaning lack of space to breathe, even if I do have certain problems in that regard, but that’s not the reason. It’s because I believe, and please don’t laugh, that trying to do what we do here in a lecture theatre would radically change the nature of the work. And no matter how uncomfortable things are here, everyone is free to intervene, anyone can interrupt me to speak about something else — and here we have the perfect example — none of which would be possible in a lecture hall. Because if we go to a lecture hall, I’ll be attached to a microphone – here’ it’s even worse, I’m connected to lots of other things, and I can’t even move – but the lecture hall would change everything. Because I would be in the situation of a formal lecture [cours magistral]. Of course, you might say: “But what is it you’re doing here if its not lecturing?” That opens another question but, in my view, no! that’s not what I’m doing. And if according to me I’m not giving a lecture it’s partly thanks to this room, which I cling to more than practically anything else.

If you tell me that things are bad, especially for those who get here after a certain hour, that conditions are unbearable and yet we have to bear them for three or two and a half hours… please believe me that I’m not trying to be funny when I say: I’m perfectly aware of this. I know everyone feels more or less uncomfortable, starting with myself, and I assure you it’s no picnic. I remember the good old days when I had a small corridor where I could walk. I like speaking when I’m walking, that’s how ideas come to me… But that’s all over now. I know, I’m not stupid… I know conditions here are pretty unbearable. Still, they seem to me better than the conditions of a lecture hall for what we’re trying to do. And I know some of you are suffering more than others, but I also know that everyone, me included, is terribly uncomfortable in this room.

I just want to say that I think there are advantages to it, and that a certain number of you here find it advantageous enough to want the situation to go on like this. So, I respond, without rancor, truly, or provocation, that if someone finds that the advantages this room offers – meaning the possibility of a certain kind of intervention, avoiding what would befall me in a lecture hall, avoiding the form of a lecture, all of that, being able to say anything at all… It’s clear that we wouldn’t have the same rapport in a lecture hall as we do in a room like this. Here the rapport passes by way of discomfort, but in a lecture hall, it would no doubt pass by way of a horrible embarrassment, even if we would be physically better off. Or even despair: “My God, we’ve ended up in a lecture hall!”, “Shit, what is this?” There are many different ways of being uncomfortable. I just want you to know, I insist that I don’t ignore the fact that the conditions for the people at the back are extreme.

Having said that, I fully agree that there are some stop-gap measures we can take. Getting rid of the tables seems an obvious solution. Make sure that those of you who are late getting here can move freely. I can even stop, if someone needs to pass this way. I’m perfectly okay with that. But I cling to the conditions of this room for reasons linked to the nature of what we’re trying to do, which would completely change in a lecture hall. And quite simply, if someone says to me, you’re being selective, I would respond in the same way as Mathieu: if we create 50 more places here, there will be another 70 people who arrive and we won’t resolve anything that way.

We gave ourselves a relatively small room for a working environment, not at all out of masochism or because we like to be uncomfortable, but because, and I’ll say it once again, what I want to say and what others want to say can only pass by way of these bad conditions. I don’t see any way we can avoid that. If someone tells me that the working conditions here are so unbearable that they can’t stand them anymore, once again my answer, without the least provocation is: too bad it means we can’t work together. Too bad, in any case I’m staying here. And I would stay here even if it meant being alone. Which would be a dream!

Sorry if I answer you in this way, but I really don’t think you could say: “Thing would be the same in a lecture hall. We would be more comfortable, and you could do the same as you’re doing here”. I said it. Things are as bad for me here as they are for you. I know it’s not a good argument but I’m not here to take a break.

The last question you raised, and that we’ve already discussed, is that of cigarettes… They don’t solve anything, actually they make things worse. I’ve always said that if we reached a point when it’s better to ban cigarettes, I would deny myself this as long as it was possible. Obviously, if I had an asthma attack, that’s tough for me, and I would stop for the day. And I would ask you not to, but if you didn’t agree, I would just go out. It’s simple, it’s not hard to understand.

Allowing or banning cigarettes from the room has to be a collective decision. So, it’s not up to me. Except when I have physical problems. Of course, anyone could have physical difficulties and say no, you have to stop. Or they could go out. Or we stop. Anyway, that’s what I wanted to say. But I insist on the fact that – I would almost like to strive to convince you, even if for me it’s clear – I assure you that if we go to a lecture hall everything will change. Everything. In the name of enhanced physical wellbeing, which I’m not even sure about – because lecture halls here are like coffins and they’re not so comfortable – everything would change including and especially the nature of what we’re doing here… [Tape interrupted] [1:26:46]

The first student: So, if I want to go over there, how do I go about it? I have to start the same rigmarole as before… [Reactions from others] Maybe that’s funny, but I’m no longer amused, I can tell you. For what I can understand the problem remains. You presented it fifteen minutes ago, and Deleuze gave his view. And there’s still a minimal density over there [on the far side of the classroom opposite him] and a dense population here [behind him near the door]. There’s still lots of smoke. There still are tables. This is perhaps a poor composition. I’m not trying to seize power; I believe what I said, these were some suggestions. You said: “even if I end up alone”; what causes me despair that that’s what might happen. I asked myself whether I should go or not. It would be ideal if you found yourself alone. Maybe only then would we really do something. The working conditions aren’t good, so if students say: “working conditions here are no good, we’ll go and do something else”, perhaps the situation would change.

A student: What occurs in the general population, I think, [unclear words] about people’s motivations that you’re talking.

The first student: Ah no, you think I’m an idiot?

Another student: [Inaudible comments due to student voices]

Another student: You’ve got a seat; you enjoy the system. [Pause, laughter, brouhaha]

The first student: You’re the privileged and we’re the excluded. [Pause, brouhaha]

Another student: It’s thirteen and a half minutes now that we’ve been talking about chairs. I’ve counted them. Thirteen and a half minutes. I’ve counted them. [Pause, brouhaha] So where are we going with this? [Pause, brouhaha]

Another student: We can get rid of the tables if that’s the problem, but let’s not take two hours about it. [Pause, brouhaha]

Another student: It’s clear this lesson is over! [Pause, brouhaha] [Tape interrupted] [1:28:32]

A new first student: What is this Vincennes mystique anyway? Can you explain it to me? Is it a new church? I don’t know it.

Another student (softly): There is no Vincennes mystique.

The new first student: So what is this mystique?

A woman student: There’s no mystique of Vincennes, there’s just the reality of Vincennes.

The new first student: So what is the reality of Vincennes? [Different voices, answer lost]

Different voices: Aaaah! Aaaah!

The new first student: So you see? There’s the real problem.

Another woman student: You’re really [lost word]. You sat down in a chair a while ago.

The new first student: Why don’t you sit down? Take a seat.

Another student: So, in the morning, I like to sleep in. [Pause]

Different students: Aaaah! Aaaah!

Another woman student: And what about us? You think we don’t? [Pause, different voices] [89:00]

The first student (from the beginning): I come here, and I want it to enjoy myself, not get all this hassle.

The new first student: There are those who like to sleep in get up at 6:30 to have a chair.

Another student: You get up early!

The new first student: There are those who get up at 6:30 just to remain standing.

A woman student: It’s completely stupid what you’re saying. Is this a struggle for life?

Another student: Yes, yes, yes!

The new first student: No, come on! Don’t be so stupid! We don’t have more than 400 seats in this room. [He tries to continue but the woman student speaks over him]

The woman student: There is one single chair and 100 people who want it. Only one’s going to get it…

The new first student: When there are 400 people here, they’ll be piled up to the ceiling. [Pause] Is what I am saying right or not? [Pause] So you see, that’s the way it is.

The woman student: I don’t follow your logic.

The new first student: What a shame. [Laughter, applause; Deleuze is visible laughing and smoking]

Another student: We have to divide the space into… [Indistinct comments]

Another student (near the microphone): Can I please have a cigarette?

The woman student: And the workers who get here late, what do they do?

The new first student: In any case, I agree with Deleuze… let’s stay here! [General laughter]

Another student: There are people standing who don’t say anything! [Laughter continues, including Deleuze]

A woman student: Can’t we all move a little bit over towards the window there, so this can all be done? [Pause] So can everyone… Can’t we move a little bit to the left? Can’t we try to squeeze up a bit. So, we can get this over with. Stop being stupid.

A student: [Inaudible response]

The same woman student: There are still another 50 people outside the door. So, let’s squeeze up! [Pause, different voices, inaudible]

Another student: We can swap places! Those who are now sitting can stand. [Pause, different voices]

Deleuze: Yes, well… I remind you that one thing is true about what you’ve been saying, Before, the tables weren’t there. [Pause] So until now… [Pause, someone makes a comment to Deleuze] No, non, but if possible next time… [Pause], this is the first time, it’s the first time the tables have reappeared.

A student: It’s sabotage! [Pause]

Deleuze: Yes, this is a sabotage of the classroom. Maybe it was you who put them there. [Laughter, pause] So, is there any way… [Pause] Right now, I think trying to get rid of the tables, that would really be a mess because… [Pause] Is there’s no way we can make a rotary movement that will allow us to …? [Pause]

Another student: We can break off for 5 minutes to move the tables outside! [Pause, different reactions]

Another student: Are you crazy? It’s already 12.10. To have everyone leave and then remove all the tables will take two hours!

Another student: We could put them…

A woman student: Those who are seated could pass their chairs over…

Another student: Why don’t we have a 10-minute break?

Another student: It’s not possible!

The preceding student: Are we having a break or not?

Another student: Everyone has to go out now… [Pause, diverse voices]

The preceding student: Are we having a break or not?

Another student: The lesson finishes at 1. [Pause; Deleuze is seen silently reflecting]

Another student: There is no pause. We’re just not continuing.

The preceding student: Everyone goes home at 1.

The preceding student: But we’ve been arguing like this for half an hour already…

Another student: If we go out … [Pause] if we go out, it will take until next Wednesday to get back in! [Pause, diverse voices; a dog barking is vaguely audible]

Deleuze: It’s all the dog’s fault! I told you… [Laughter and pause; tape interrupted] [1:33:11]

A student: I’d like to ask Deleuze if, hypothetically, we could take out the chairs that are already there. There would be much more space.

Other students: No, no, no….

Another student: No more on this topic; let’s talk about something else… [Pause; diverse voices]

A woman student: [She is speaking to someone in a low voice, inaudibly, then] … if there are no chairs, it becomes a room like any other… [Pause, diverse voices]

Deleuze: What? [Inaudible comments]

A student: No, it’s the same thing. [Pause, diverse voices]

Another student: Let’s stay here!

Deleuze: I think, at least in part, [Pause] following what you said… I am feeling things here; I can’t even think any more. I am feeling things, and I think: “My God! I feel worse and worse…” [Pause] So you arrive here [Deleuze indicates the first student who spoke at the start of this section of the discussion], and you say, “What is this? It’s my first time here, what is this? How awful we feel here! How awful you poor chumps must be feeling! What’s the matter with you? What is it with you that you want to feel like this?” So, someone says this, points this out, and I listen, and I tell myself: “That’s right, it’s true, we feel so bad…” [Pause] On the other hand – and in saying this, I’m not saying that you’re exaggerating – there are cases in which I’m sure that, even over there in that abominable corner [Deleuze indicates the area near the entrance where the first student is located], when things are working… [Pause] — I’m not saying for everyone, or for everyone at the same time – [Pause] we forget our discomfort, [Pause] we don’t think about it anymore. [Pause] Because, at that moment, things are really working well. We feel uncomfortable, but we forget about it… [Tape interrupted] [1:35:28] [On the video, a new title sequence appears, as if this were a different day, but the same session and the same discussion in progress continues]

The first student from the beginning: Simply it seems to me that…

Another student: … what’s more, they weren’t even listening; you have to start over…

The first student: I just want us all to be able to work in an egalitarian way, all of us seated in the same conditions. If it should happen that the group doesn’t agree that we should work in an egalitarian way, with everyone having a seat, and putting the tables against the wall so people can sit on top of them, if would only take 5 minutes to do that, instead of half an hour of arguments… if the group doesn’t agree to that, then I’m leaving.

Another student: So what do you do with all those who can’t get in when the others are all seated?

The first student: We’ll see about that later, that’s in the future!

Another student: The future has already been going on for years!

The first student: Let’s give the experiment a try, and then we’ll see!

The previous student: We’ve already tried it!

Deleuze: Yes, once more, I am responding to your proposal, but only…

The previous student: We’ve been working without tables here for years, and people always end up standing in the back.

Another student: But there are more people this year, I think…

Another student: That’s not true; there have been as many student for the last two and a half years…

The previous student: Listen to me…

The previous student: … It depends on the period. When the weather is nice, there are fewer here.

Deleuze: I would like to answer… Considering the hour, it is out of the question to try to remove the tables now. [Several students say, “Yes, yes”] As I said, it’s the first time the tables have resurfaced, and I insist on this point because… [Interruption, diverse voices]

A student: It’s not a question of removing them… just of moving them out of the way!

Deleuze: Yes, but even just moving them will take half an hour!

Another student: There’s not just this classroom, Deleuze’s class…

Another student: At 1 o’clock, there’s another class; at 4 o’clock, another class, and at 7 o’clock, there’s another class here, every day… [Pause, diverse voices]

Another student: Where do you want to put the tables?

The first student: I want to move them so we can sit on them! … [Tape interrupted] [1:37:30]

Deleuze: This is what I propose we do. He made a suggestion and so here’s mine. I repeat, we won’t have the tables anymore just as we didn’t have them before. The tables will be gone, starting from the next lesson. It won’t be hard to get rid of them. If there’s a [Deleuze indicates the entrance or the hallway] there, a room where we can put them, those who need them for other lessons can go and get them there. Those who don’t want to remove the tables don’t have to do it. Those who want them gone can do it when they arrive and can put them either in the room next door or in the middle room. Starting from next time, no tables will be here except a small one for the books. There you have it… [Tape interrupted] [1:38:36]

A student: It’s a question of adding some tables, not taking them away.

Another student: It’s not true because rats have no resentment against tables.

The first student from the beginning: I don’t give a shit. You can judge my level of resentment when I’m gone.

Another student: Speak simply!

Another student: You should be ashamed of yourself, listen, you’re not so important! [Laughter; pause, diverse voices]

Another student: What’s the reason… what’s stopping us from putting the tables against the wall? [Students groan at this question]

The first student: That’s what we were talking about earlier. Are you thick? This isn’t possible!

Deleuze: The answer is quite simple, which is there’s 20 minutes.

The first student: That’s what I proposed! Aaaah!

Another student: We only have 20 minutes left. It’s not worth it.

Deleuze: It’s true. There’s 20 minutes, and the time it would take is 20 minutes because… And where do you move the tables if these guys don’t go out first?

The first student: 20 minutes to push the tables against the wall?

Deleuze: Obviously, because everyone would have to go out.

Another student: And in 20 minutes the lesson is over. It ends at 1. There’s a half an hour left.

Deleuze: [Brief, indistinct remark]

The first student (answering someone’s question): So that we can sit on the table… [He continues, indistinct words]

A woman student: If we have to take the tables out, let’s do it!

The first student: But we can do it now. Why wait until next week?

Another student: We just explained to you that there are other courses in the meantime.

The first student: Let’s leave the tables here and push them against the wall.

A woman student: Don’t you want to talk about something else? [Pause, diverse voices]

The first student: But of course! Of course!

Another student: He’s a mystic… that guy.

Another student: No, he’s nice.

Another student: Oh, you’re a clever guy, a clever guy!

The first student: The question I raise is why is it such a problem for the group to move the tables…

A woman student: Because it’s impossible!

Another student: What a mess!

The first student: If it was possible, we would have already done it.

The previous woman: It’s impossible! [Pause; diverse voices; Deleuze is visible, smoking, waiting]

A student: How about we continue?

Another student: Continue what?

The student: What were we saying?

Deleuze: Aaaah! [Pause]

A student: It’s about delirium! [Silence in the classroom]

Deleuze: Fine. [Pause, he continues smoking] Okay, so we can agree [Pause] to make the tables disappear for the next time.

A student: Yes.

Another student: Yes, we’re agreed on that!

Deleuze: Fine. Isn’t there some way for someone to slide over a little… [He makes gestures toward the crowded entrance] there, along the wall?

A woman student: We can make a corridor. [Pause, diverse voices]

A student: Of course, as long as they make the effort to move. [Pause, diverse voices]

A student: But there’s space on those tables over there, or do you prefer to continue suffering? Either you can either grin and bear it in your corner or sit on those tables as has not yet occurred up to now. Because, you see, no one is going to move the tables.

The first student from the beginning: There’s a lot of space on the window ledge.

The preceding student: So that your ass will be in our faces! [Pause, diverse voices]

The first student: If they sit on those tables, those behind will have their noses squashed against their backs. So that won’t work on the tables, I agree. I’m fine with that.

The preceding student: So now it’s a question of the schedule. That’s it. Either we go now or we continue; if we continue, either you guys just grin and bear it, like that, voluntarily…

Another student: And shut your traps!

The preceding student: Or you park your carcasses on them [the tables]. For the moment, there’s no other solution, to do it voluntarily.

The woman student (near the first student): In any case, I don’t feel like sitting down, I don’t feel like doing anything now. I’m finding all this so delirious that …

The preceding student: Ok, we’ve understood. You’re disgusted. There’s only one thing left for you to do, that’s to get out!

The woman student: And you can stop being such a pain in the ass! Wait for me to make my own decision.

Another student: It’s always the same rigmarole. How is it that you’re in France and you … [Indistinct words]

The first student: You’re entirely correct. I’m a fascist pig! I just wanted to say it.

The preceding student: Ok, then, there you are!

The first student: Thank you. I was expecting that. That works for me. It took 22 minutes for it to come out. No, sorry, 32 minutes. [Pause, diverse voices] By the way, I really enjoy being a fascist!

Another student: But anyhow, [Deleuze is visible listening and smoking] there are people sitting and people standing.

The first student: How about that!

The preceding student: Normally one comes here alone, and now we’re not! [Pause] It’s interesting you can find all these comrades so quickly. [Pause] Don’t you think so? You’re all standing over there, and now you are standing there together, and you tell us you don’t have seat, and you say with such attitude.

The woman student: Ah, you’re being a pain in the ass!

The preceding student: Fine!

Another student (the one who suggested she leave): Time to go, darling…

Another student: And the same goes for you!

The preceding student: Why?

The other student: You ask why? Because your being such a pain in the ass.

Deleuze: Oh… things are going badly. This is getting ruined. [Pause, diverse voices, then a silence]

Another student: Where do you see all these empty chairs since there aren’t any?

The first student: We would need 50 chairs to accommodate everybody. How is that possible? [Pause; diverse voices] Count them. Be realistic. Count them and see if there are 50… [Pause, diverse voices]

Another student: Oh my God! Not again!

The previous student: [Unclear words; subtitles: Shut up!]

The first student: How do you explain that you’re standing and I’m sitting? I think someone should find him a seat so see if it’s reasonable for him to sit, and if there is a reasonable solution left. [Indistinct words; pause] I’m just blowing smoke out of my ass… [Diverse voices]

Another student: If you are, then stop blowing it out your ass?

Another student: Go ahead, that’s ok! You’re unblocking yourself! [Laughter]

The first student: I came here to listen to Deleuze, but I didn’t imagine any of this.

A previous student (who gave the woman student the choice to leave): And maybe that’s your problem. You came to listen, and you spoke up plenty. Since you came here to hear him. That’s your problem. You came to listen.

Another student: [Inaudible comment]

The previous student: There you go! It’s better already.

The first student: Hey guys, when you’ll get finished speaking about my problem! [Laughter, pause] I know what my problem is. I don’t need others to speak about it. Speak about your own problems. All you guys sitting down for the past half hour, don’t you have a problem?

The previous student: Not at all.

The first student: Not at all?

The previous student: We’re really fine!

The first student: Bravo! [He applauds]

The previous student: None at all!

The first student: Guys without problems! Bravo!

The previous student: Thank you, pal!

The first student: I’ve read things [He points toward Deleuze] about microfascism…

The previous student: It’s not enough to read about it, you have to live it…

The first student: … I’m making some connections now…

The previous student: Hey, fascist number two!

The first student: [Some lost words] … There’s something that’s missing here. [Pause, diverse voices] I myself prefer to understand and be aware and try to exclude microfascism…

Another student: That guy hasn’t understood anything!

The previous student: We’re sick of your infantile power! [Pause, diverse voices; the first student appears visibly annoyed]

The first student: What? What? You think you’re a responsible adult maybe? [Pause, diverse voices] What kind of power do you think you have? [Pause] Do you have a solution for the 50 guys who are still standing? You and you’re responsible power?

The previous student: We’re having a great laugh, and then talking…

The woman student (near the first student) Hey, that’s not fair! You’re all sitting, you having a laugh! [Pause as she smiles, diverse voices]

The previous student: [Indistinct comment]

The woman student: You have everything… how unfair! [Pause, diverse voices; she bends to listen to something the first student tells her]

Another student: Will you allow me to decide for myself?

The first student: You want to regale us with your problems?

The student: We’ve had it up to here with your problems!

The first student: My problem is also yours? On that I agree. [Pause, diverse voices] So the solution to solve everyone’s problems… is for me to leave.

A woman student: No, no, stay. Stay! [Pause, diverse voices, laughter]

The first student: Are you only inviting me, or the others too? [He indicates the crowd behind him]

Diverse voices: Everyone! Don’t go! Stay with us!

The first student: So, are you inviting just me or everyone? There’s 40 or 50 of us here. [Pause, diverse voices]

Another student: Are you acting as their spokesperson?

Another student: Stop that!

The first student: No, I speak only for myself. [Very long pause, diverse voices, laughter]

Dog: [Barking is heard, also much laughter; voices of students in discussions, more barking]

A student: So, give him a chair! [Laughter]

A woman student: We can’t manage to find it. [The pause continues, also the barking]

A student: It was Deleuze who mentioned the dog.

Deleuze: In any case, we must be precise: our lessons don’t lack variety. [Pause, laughter] So, there we are… I’d like to… The chairs, all at once the chairs became… [Pause, Deleuze does not finish the sentence] Everything’s fine for me, everything’s fine, I mean… In fact, I have a confession to make; I’m feeling a bit sickened. Two times we’ve had, we’ve really had a bit of internal variety during a lesson. The first times we spoke about the face… [Noise, laughter; Deleuze and everyone turns to Deleuze’s right to someone near the board, off camera]

A student (near the board): The close-up…

Deleuze: That’s right, the close-up. [Pause] And then when we spoke about the close-up, [Pause] And suddenly… — There’s this unbearable cur — and suddenly, these chairs have become, they’ve become a kind of proliferation: the fewer there were, the more… Well, that’s okay. So, I propose again what I was saying regarding the chairs, everyone will maintain the same discomfort, if you don’t mind, and I’ll speak again for another five minutes, and then I’m done for today. For the moment, we’ve finished with the close-up unless you have something else, and then we’ll consider it next time. We can still carry this [A sudden brief high-pitched microphone sound from the film team] incompleteness of the close-up with us.

I want to end today, going back to the topic we touched upon the other day, which consisted in saying this: in the end, there are two types of delirium – no, it wasn’t at the end’ we started with this — aren’t there actually two forms of delirium in the classification that concern something fundamental, which is to say forms of delirium without…

The first student: We haven’t resolved the problem, so I’m going!

Deleuze: Okay! [Pause; voices of students complaining about the student’s words]

The first student: This is the complicity of a group unable to resolve its problems…

A woman student: No, really, listen… [Pause]

The first student: Ciao!

Deleuze (Pause for a small coughing fit): Aaaah… And so…

A student: The man without a face.

Deleuze: It’s funny the way things happen, don’t you think? It’s funny… In this group of deliriums with no intellectual impairment, with no intellectual deficit, we identified two forms. And as we said, it wasn’t by chance that psychiatrists of the 19th century tried to confront this problem and in the end were poisoned by it… I’m speaking on one hand about the group of so-called paranoid delusions, delusions of interpretation, and on the other about the group referred to as grievance delusions or passional delusions. Next time we’ll look at some texts. [Let us note that the distinctions developed here appear in Deleuze’s “Two Regimes of Madness”, from which the collection of essays takes its title, Two Regimes of Madness. Texts and Interviews 1975-1995, ed. David Lapoujade, trans. Ames Hodges and Mike Taormina (2003; MIT/Semiotext(e), 2006), pp. 11-16. The text was first presented, with Guattari, at a conference in Milan in 1974, and then was published in the edited volume Psychanalyse et sémiotique, ed. Armando Verdiglione (Paris: 10-18, 1975). On the paranoiac-passional distinction, see also A Thousand Plateaus, plateau 5, “On Several Regimes of Signs”.]

I’ll remind you that the difference, even in terms of the schema, consisted in this: the paranoid delirium or delirium of interpretation was constituted around a centre, a matrix, a dominant idea and proceeded by way of circular networks, seizing upon everything, the most heterogeneous elements, a bit of this, a bit of that… [Deleuze makes gestures left and right] the chairs, a guy passing by the window; it seizes upon everything, everywhere, everywhere…

A student: The dog…

Deleuze: The dog! [Laughter]

A student: The man without a face…

Deleuze: And all of that… [He makes a circular gesture] it all forms a kind of expanding circular irradiating network in which everything is captured. And paranoiacs… proceed in this way. And not only paranoiacs.

On the other hand, you have a completely different form of delirium. In this case it’s as if a little packet – and here I need to use the word “packet” — a little packet of signs starts to flow along a line and then arrives at the end of a first segment and begins another segment. And after the second a third… In this case we have, in a single sector, signs that flow on a segmented line waiting for the first segment to be completed before beginning the second. It’s a limited delirium, beginning from an isolated packet of signs that pour onto a segmented straight line. A succession of linear proceedings instead of an expanding, irradiating network.

I know you’d like me to quote some examples at this point… but we’re not there yet. We’re not there yet. These are two very different figures. The passional is someone who has an extremely localized delirium, that doesn’t at all seize upon everything. And what’s more, they continue to be perfectly reasonable. There’s just one thing, a sign. In erotomania, which forms part of the passional delusions, there’s a sign that flows along its line and that has its history. After which the first proceeding comes to an end. And then a second proceeding begins. There might be a pause between the two. The passional remains calm, regains their strength and then starts over, and then it starts over. In this case, we have a linear schema. Are the two figures opposed or can they unite?