May 19, 1987

I would first like to speak to you about practical things, and I’d like you to excuse me for speaking practically to you in this way, and I am telling you rapidly that my health is rather so-so … and I have to take a rest. … So, I will rather quickly cease teaching courses. … It’s not that this is the most divine activity in the world, not at all, but it’s such a special activity. So, I am going to stop rather quickly, but … I am going to teach two more courses … on what I had intended, that is: harmony and comparison of musical harmony in Leibniz’s era, and about what Leibniz calls harmony.

Seminar Introduction

In his introductory remarks to this annual seminar (on 28 October 1986), Deleuze stated that he would have liked to devote this seminar to the theme “What is philosophy?”, but that he “[didn’t] dare take it on” since “it’s such a sacred subject”. However, the seminar that he was undertaking on Leibniz and the Baroque instead “is nearly an introduction to ‘What is philosophy?’” Thus, the 1986-87 seminar has this dual reading, all the more significant in that, unknown to those listening to Deleuze (and perhaps to Deleuze himself), this would be the final seminar of his teaching career.

Deleuze planned the seminar in two segments: under the title “Leibniz as Baroque Philosopher,” he presented the initial operating concepts on Leibniz, notably on the fold. Circumstances during fall 1986 limited this segment to four sessions with an unexpected final session in the first meeting of 1987 (6 January). For the second segment, Deleuze chose the global title “Principles and Freedom”, a segment consisting of fifteen sessions lasting to the final one on 2 June.

English Translation

The session opens with Deleuze announcing he will end his teaching career after the June 2 session, and so this session’s theme, “what does it mean for Leibniz, having a body?” precedes the final sessions on harmony. Deleuze points out, though, that without a body, there would be no perception, but from previous examples, Deleuze concludes that as perceptions are data inherent to the monad, the monad would be full of perceptions, even ghostly ones, but that having a body corresponds to the event’s double requirement, that of both preceding itself and succeeding itself. Here, Deleuze refers to Joë Bousquet’s statement that the problem is being worthy of the event, and Deleuze explores this with the virtual-actual rapport in Leibniz, arguing that the event, as virtuality, refers back to individual substances that express it. Moreover, this is not only a virtual-actual rapport, but also possible-real rapport since the body remains pure possible without being actualized in a body. Returning to the Baroque house with two floors, the lower connecting to pleats of matter, the upper to folds in the soul, Deleuze argues that Leibnizian reason regarding these floors is the event, which must actualize itself in the monad and must inscribe itself in a lived body. Deleuze returns to an earlier point, that Leibniz needs animals (and perhaps invents animal psychology) since they force us beyond human souls and thus to agree that there are bodies, concluding that for the morality of the event, the two coordinates are being worthy of what happens and to inscribe it into one’s flesh, and the two floors for Leibniz are the circuit of the event, the event not only actualizing itself in monads, but realizing itself in the body. Here Deleuze arrives at Leibniz’s three aspect: the soul and folds in the soul; matter and pleats in matter; and between them, a “realizing thing”, that which brings the lived body to the monad, i.e., the rapport of the folds in the soul with the pleats of matter for which Deleuze proposes the name, vinculum substantialae (the “substantial vinculum”), a chain or knot that intervenes as a kind of stitching of the living body.

Deleuze returns to the seminar’s start, the definition of the Baroque, in which folds extend to infinity, and Deleuze takes an El Greco painting (“Christ in the Garden of Olive”, with several versions) to note the fold’s three registers: folds of fabric, folds of boulders, folds of clouds. Deleuze calls these the “textures of matter” for Leibniz, and Deleuze reviews this genesis, with the monad containing everything, expressing the entire universe, but only clearly in a small, privileged region. To this first proposition, Deleuze adds the second, I have a body from which I express the entire world but again only in a confused way. From here, Deleuze considers a hierarchy of monads, some in complete darkness, animals with a tiny clear region (e.g., the cow’s field), reasonable souls with a clear zone of expression but also in a confused way. Then, considering how the body is an object of perception, Deleuze returns to the tiny unconscious perceptions that arise through which we create a conscious perception. Deleuze explains how the most confused thing in the world can communicate a clear perception to the monad, and he relates this example to an earlier one, the dog beaten by a stick, the experience of pain, that Deleuze develops by reading from two Leibniz texts regarding sensation in the monad and corporeal traces of the body. Deleuze insists on the contrast between bodies, exerting direct causality on each other, and monads, doing nothing other than inter-express a one and same world, without doors or windows. Thus, Deleuze proposes for the penultimate session to consider the story of harmony implicating itself between monads and bodies.

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Leibniz and the Baroque – Principles and Freedom

Lecture 18, 19 May 1987: Principles and Freedom (13) – What Does It Mean to Have a Body?

Initial Transcription by Web Deleuze; Augmented Transcription and Translation by Charles J. Stivale (duration, 2:14:05)[1]

Part 1

Richard Pinhas: This is a question on zoology in relation to the previous session, and I am also posing it in the context of Leibniz as well as Gilles’s problematic, which is first, which gets articulated as: is there a possible passage, as concerns anxiety (inquiétude) that Gilles discussed — the anxiety of the rabbit that is being hunted, but also anxiety in perhaps a more general sense – can this anxiety concern, must it concern other creatures, notably man? And on the other hand, if that still remains anxiety in as strong a sense as we’ve understood it, is this anxiety linked to what modern phenomenology calls worry (le souci)? How do you conceive of this articulation between anxiety and worry, of a possible connection or a possible exclusion between anxiety and worry? So, it’s a question on zoology.

Deleuze: Mmmm. [Pause] The second aspect of the question, it’s up to you to answer it. [Laughter] [Pause] Good.

Everyone can hear well, because I’ve been told that often, in the back, you were hardly able to hear me? This seems to me to be rather important. [Laughter] So, here we are. I would first like to speak to you about practical things, and I’d like you to excuse me for speaking practically to you in this way, and I am telling you rapidly that my health is rather so-so [moyenne], my health is rather so-so, and I have to take a rest. So I’m going to… But it’s really ok; so-so is already not so bad. So, I will rather quickly cease teaching courses. In any case, the fact I’m going to stop is quite perfect. I’m going to do so in the following way because, besides, I just can’t manage any more. I feel that the moment has come; I’m not managing it anymore. It’s very special, teaching courses, you know, it’s very odd. There is a moment at which one feels quite clearly that the time has come given how long we’ve done [this]… It’s not that this is the most divine activity in the world, not at all, but it’s such a special activity. I’ve thought about this, but anyone, no matter.

So I am going to stop rather quickly, but I nonetheless am going to finish what I wanted to, that is, today I’m going to, but you will see in what form, and I am going to teach two more courses, two courses on what I had intended, that is: harmony and comparison of musical harmony in Leibniz’s era, and about what Leibniz calls harmony. So today, we are going to have a session about which I am going to explain to you what I’d like us to do, and the next two sessions will be on harmony in which I will truly need the contributions of two participants here, competent in music. But I need other people as well.

Generally speaking – that I am accelerating a bit the end of classes is not serious because we have done more or less what I hoped for, in the end, the essential part of what I had wanted to say about Leibniz. I will still come to class in June, but uniquely to see students, either in the premier cycle or deuxième cycle, or about theses, those who need to see me and that usually I never have the time to see. So you will consider this from the viewpoint of our work in common, you will consider that there are only two more classes, which makes the 27th [actually, the 26th] and at the start of June. After that, I will no longer be speaking. [Pause] So there we are.

Having said this, today, I would like this to be a very calm (douce) meeting because I admit that [Pause] it seems to me that it’s a domain in Leibniz’s thought [that’s] at once so complex and mysterious and so ahead of his time, on other levels, I don’t know. So this is a domain that I summarize in this form: what does it mean for Leibniz, having a body? What is that, having a body?[2] And I am going to try to do the most, I don’t know, not like I have done in other sessions because, for me, in my reading of Leibniz on this, the questions abound frequently more than… [Deleuze does not complete the sentence] And if I don’t succeed [in understanding], I would tell you. Fine, here’s what I am not managing to understand. [Pause]

We started off from this, you recall – I am tossing out rather separate points – we started off from this, that the individual substance, the monad, which is pure spirit (you recall, we saw it in this form: it is pure spirit, it is soul or spirit), we have seen that the individual substance had two requisites: it was active unity spontaneously produced from its own predicates. Notice that this is already not easy: what might it mean, a predicate like “I am taking a walk,” whereas the subject is the monad as pure soul? It’s taking a walk, the soul; what does that mean? Someone will say: it’s that, on the other hand, there’s already a body — no! If you follow my difficulty, it’s: No, we know nothing at all about it. Why do we know nothing at all about it? We don’t know if there aren’t grounds to be Berkeleyian, as we said the last time, specifically: there are perceptions, yes, there are perceptions in the monad, and interiors in the monad, so at the outside, I could say: I perceive myself taking a walk (me promènant). What is in the monad cannot be the walk. What is in the monad is the percipit, it’s the perception of the walk.

I would like you to make an additional effort because we can sense that this is not going right. If there were no body, there would be perception, that’s agreed, but would there be perceptions of the walk? That seems strange. I take a text from [Pierre] Bayle, you know, in his “Objections to Leibniz.” In his “Objections to Leibniz,” Bayle says, in general, even not in general, he says precisely: you remember the story of the dog, the blow of the stick he receives when he eats, etc. And he says: But the monad of the dog thus perceives in a confused way the blow of the stick that’s being readied – perception of the blow of the stick – and then, grasps the pain while the blow of the stick is being readied in matter, and that the stick, as body, strikes down onto the dog’s body. But as Bayle says: at the outside, nothing requires there to be bodies, and in my opinion, the monad of the dog could very well link up the perception of the stick and the perception of the blow. God would have constituted it in this way, but there would be no bodies. That’s indeed what [George] Berkeley will tell us. [Pause]

What causes me to say: “there is a body?” These examples bother me. It’s true that from an absolutely logical viewpoint, I can say: the monad of the dog passes on from the perception of the stick; it does not pass from the stick to the blow, since it is purely spiritual, but it can pass from the perception of the stick to the perception of the blow; it passes from one perception to another. These perceptions are data, in fact, inherent to the monad. So this, I can say it, but it’s really strange: if there were no bodies, it would be rather strange for perceptions to be perceptions of a pseudo-body. It seems to me that if there were no bodies, the monad would be full of perceptions, but these perceptions would be of another nature than perceptions of ghostly strikes from a stick. [Pause] Fine, I get all that.

And when Leibniz answers Bayle: why yes, why yes, this would, in the extreme, be possible; it would be possible that no stick would exist and there would be no dog’s body, that would not prevent the dog monad from having a perception of the stick and of having a perception of the blow as a form of pain. We tell ourselves: in the end, ok, fine, but all that is just a manner of speaking. What does that mean? Why must there be bodies? Having a body! At the point where we are, in fact, we have well defined “monad”, [so] why must there be bodies? I tell myself something: perhaps the requirement of having a body belongs most fundamentally to the world of the event. [Pause] One might almost say that the event has a double requirement, and if you grant me that we have spent quite a long time questioning what an event is, while considering it as a double secret of Leibniz’s philosophy, I would say: yes, there is no event that is not directed to the spirit. Perhaps events are not eternal essences, but in a certain way, perhaps events spy on us and wait for us. [Pause]

A student: Can I say something?

Deleuze: Yes.

The student: A small comment on the level of the event. Someone who seemed very qualified to talk about this was Ferdinand Braudel. Very close to the end, he said: the event is a bit like an explosion of dust, like fireworks, and after, everything settles back down into night and darkness. It’s a phrase from Braudel. I mean with this that if the event is necessarily crucial, hence the necessity of a body, a problem presents itself of the continuous and the discontinuous. Braudel presented events – and he even had, anyway, when he was speaking of the event, he knew what he was talking about – and so it was something discontinuous, that exploded like that and then after, fell back into a kind of darkness or night, hence the problem of the continuous and the discontinuous. In that time, what is the body doing? I mean, is it on vacation, is it out strolling around? It is not necessarily substance, it is not always plugged in, as some would say today, into the event in a kind of constant tension, since the event really appears like that only as a kind of explosion that surprises us, and after, we get out of it what we can, but after, once more it’s darkness, it’s night. [Pause]

Deleuze: I would like to say, with very great respect, and let this be really a suggestion: don’t mix things up. You tell us: yes, Braudel says such and such. And certainly, what Braudel says is beautiful, but I am not sure that it implies the discontinuity of the event that you state. But in the end, we can talk about it. But we ourselves, we remained on the event for several weeks, for example, not from Braudel’s works, but for example, on the event from Whitehead’s works, and Whitehead told us: be careful, you recall, an event is not someone who gets run over; it is that also, but ten minutes spent in this room is an event, even if absolutely nothing happens. It’s an event. The passage of Nature, as he says, in a location is an event, it’s an event. Two minutes in the life of the Grand Pyramid is an event.

So, fine, when we’ve analyzed… and this is why I feel no need to go back into Whitehead since we have done so. We have analyzed all the thickness of explication and definition that Whitehead proposed to us about the event, from the convergent series that implied, the prehensions, the prehensions of prehensions, etc…. If we began to study Braudel, I believe we would have other definition, other values about the event. In my opinion, these would have some very, very important points of contact. So, I am saying, in any case, one must not take on too fully a historian speaking to us about the event in history since we are involved as well with the event everywhere, an event here; someone lighting a cigarette, it’s an event. If there is a light [for the cigarette], it’s an event, [Laughter] but there are really events that are entirely from all directions [de tous courants].

So what I mean is, once I’ve agreed that we can ponder this, well fine, does this connect to Braudel, and to what extent does that connect, for example, with what Braudel is saying? I myself have a feeling that the event is double, that it’s a bifurcation, that any event is bifurcated. Why? First, because any event precedes itself, just as it succeeds itself; that’s why I said: don’t judge everything too quickly; about one continuity and one discontinuity, we know that an event indeed risks preceding itself and following itself. [Interruption of the recording; text from Web Deleuze] [18:32] But insofar as it precedes itself and follows itself, this is… Leibniz: the perception of the stick precedes the blow, but the perception of the stick, the evil man sneaking up behind the dog, this was already an event. [Return to the recording]

Part 2

Every event precedes itself, every event follows itself. [Pause] In a certain manner, one might say: every event waits for me! And it’s already that. What interests me is a morality (une morale) of the event, because I believe that there is no other morality than that of the nature of people in relation to what occurs to them.[3] Morality is never: what must one do? [Rather] it’s: how can you stand what happens to you, whether this be good or bad?

One of the greatest moralists of the event is the poet Joë Bousquet. Bousquet suffered a ghastly wound that paralyzed him, and among other things, everything that he tried to say and explain was in some manner: this event, I was created to incarnate it. That is, starting from this, his problem was, in a certain manner, being worthy of the event. You certainly sense that there are people who are unworthy of the event as much in happiness as in misfortune. Being worthy of the event, however tiny it might be, this is why this is a very concrete morality; this doesn’t mean being serious (grave), certainly not, it’s not about that, but there are people who create our suffering, [and] why? Because, in some ways, they render everything mediocre, both the good that happens to them and the bad. You indeed sense that there is a certain way to live the event as being worthy (en étant digne) of what happens to us in the good and the bad. I would say that it’s this aspect through which every event is addressed to my soul. [Pause]

What makes those who whine (les gémissants) so difficult to be around? They are not worthy of what happens to them. You will tell me: what happens to them… unless I am already saying too much by saying that whiners aren’t worthy of what happens to them, for there are whiners of genius. — I would almost like this to be this way all the time; I can’t suggest a sentence without having to withdraw it — There are whiners/wailers who are worthy of what happens, it’s even these ones that are called prophets, the prophet in his fundamental wailing. There are some who take wailing to a level of poetry, elegy, and elegy means the complaint … There are some that complain with such nobility; think of Job. Job’s complaint is worthy of the event.[4] Fine, I cannot even speak. Each time I have to withdraw it, but you can correct [it] by yourself. I am simply saying: every event addresses itself to the soul or the spirit. So, I understand a bit better; there are events that address themselves particularly to the soul. At the extreme, I would say: ok, I understand suddenly a little something, that we might be able to tell ourselves that taking a walk is an event of the spirit, and that we might be able to count “I’m taking a walk” among the predicates of the monad, yes. At least, this gets us a bit farther forward there.

If I try to create some terminology, I would say, at least this explains to me a few words that Leibniz uses constantly: virtual, actual, the virtual, the actual. We’ve seen this. We’ve seen that he uses [the terms] in rather different senses.[5] [Pause] First sense: each monad, you and me, each individual substance, is called “actual”. It expresses the totality of the world, but this world, you recall, does not exist outside the monads that express it. In other words, this world that exists only in the monads that express it is in itself “virtual”. The world is the infinite series of states of events, [so] I can say: the event, as virtuality, refers back to individual substances that express it. It’s the virtual-actual rapport. What does this rapport imply? When we tried to define it, we arrived at the idea of a kind of torsion: at once, all monads are for the world, but the world is in each monad, which gave us a sort of torsion. And very often, Leibniz uses the terms virtual, actual. I am simply saying: in whatever sense that this might be, he will tell us, for example, that all innate ideas, all true ideas, are virtual ideas, that they are virtual; he will use “virtual” in other cases, but in my opinion, always in rapport with the actual, and to designate the rapport of a type of event with the soul. And nothing, nothing can remove from us the idea that this is not yet adequate, and that, however profound the event might be, to the extent that it expresses itself in the soul, something will always be missing if it also isn’t realized in the body, and that it has to go all the way there. It has to be inscribed in a flesh (une chair), it has to be realized in a body, it has to mark itself in a matter (une matière).

This time, would it be something else? If I looked for a couple, the event not only has to actualize itself in a soul, it must also be realized in a matter, in a body. I would say: here, this is no longer exactly virtual-actual, it’s real… No, rather it’s possible-real. It’s possible-real. [Pause] The event would eternally remain a pure possible if it didn’t actualize itself in a body. It would remain a pure virtual if it didn’t actualize itself, if it didn’t express itself in a soul. It would remain a pure possible if it didn’t pass into a body. Why do I say that? Well, because for Leibniz, the two couples do function: possible-real, virtual-actual. And this is quite dangerous, it seems to me, since many commentators make no different between these two axes. [Pause] There is a fundamental difference.

In the letters to the reverend Des Bosses about whom I’ve already spoken to you, in letters to the reverend Des Bosses – yes, it’s Des [Bosses],[6] appearing at the very end of Leibniz’s life, a whole series of very odd expressions appear. The letters are written in Latin. Appearing on about every third page, so with a great frequency, the term “realisere” appears, or as a participle “realisans”, [Pause] and [Leibniz] asks: what is capable of realizing phenomena, [Pause] or what is the realizing thing (réalisant)?[7] I quote [Pause]: “Monads will influence this realizing thing, but it will change nothing in their laws.”[8] It matters little who the realizing thing is; what matters is that it not be confused with the monads. [Pause] Another text: “I hardly see how one could explain the things starting from monads and phenomena; one must add something that realizes them” — something that realizes the phenomena and monads, one must add something that realizes them.

What do I find of interest here, understand? What is real? What’s real is not matter, otherwise it would be matter that would be the realizing thing; it is obviously not matter, it’s not the body, it’s not the body either. Moreover, matter, the body, it’s what will be realized by the realizing thing. [Pause] As we will see or will try to see, the realizing thing has a close rapport not with the body in general, but with the living body, with the living. [Pause] One not only must — and this seems to me a very profound idea in a philosophy of the event like Leibniz’s, and all of his morality is engaged in this as well. It so happens not only that the event is actualized in the monad, it must be realized in the lived body (corps vécu), and in this sense, there must be a realizing thing just as there must be an actualizing thing (un actualisant). The actualizing thing is the monad itself. We need a realizing thing that realizes the event in matter, or that realizes the event in the body, precisely as there is – not precisely as, but as there is [Pause] an actualizing thing that… [Deleuze does not complete the sentence]

As a result, I come back, as someone asked me at the last meeting, I come back completely to a departure point when I said, you see the Baroque is not really, [Pause] shouldn’t be so difficult to define. And as I was telling you, the Baroque is a house with two floors, and there must be two floors. And one of the two floors connects to pleats (replis) of matter, while the upper floor connects to folds in the soul.[9] There are folds in the soul just as there are pleats of matter. No doubt it’s a kind of strange circuit from one stage to another that is going to constitute the Baroque world. You sense now that we grasp a reason, at least at the level of Leibniz, we grasp a Leibnizian reason concerning these two floors. The Leibnizian reason is the event. The event implies these two floors. It must actualize itself in the monad, yes, but it must also inscribe itself in a lived body. [Pause] When the event actualizes itself in the monad, it makes folds in the soul, [Pause] but it must live it. It’s the soul there, it’s your soul that folds itself. And when the event inscribes itself in the lived body, it makes pleats, it makes pleats in matter, in living matter.

What’s happening? I would like you to feel, yes, we are moving forward a little in the reasoning: why does the monad need the body so much? Why isn’t Leibniz Berkeleyan? Why can’t we be happy with the famous: Esse est percepi, that is: everything that is in the monad, in the end, will be perceived by the monad, and that’s it, full stop? I believe that the deepest reason is precisely contained in the event, [Pause] that the event cannot be inscribed in the soul, without simultaneously demanding a body [Pause] in which it is traced. [Pause]

And then, at this point, I stumble onto a text that I was no longer thinking about. I was thinking about all that, and I remembered something. One works that way a lot, as if I had already read that. And I told myself I had to… and I recalled a very odd book by Husserl, a book called Cartesian Meditations. This book had as its departure point Husserl’s coming to France, before the war, and he presented a certain number of talks in German, but in France, that have been taken, that have been translated under the title Méditations cartésiennes, a title that pays homage to France.[10] Husserl invokes Descartes very strangely at the beginning, but the more he moves forward, the more he invokes not Leibniz, but monads. It’s such a strange term from Husserl’s pen, and one wonders what is happening. [Pause]

And it’s especially the fifth meditation, so in the final [part], the fifth meditation in which Husserl is going… But I am telling this to you a bit, quite imprecisely, so go look at it yourself. For once, the text really isn’t that difficult. For once, it’s not terribly difficult Husserl. Husserl tells us, without even referring to Leibniz, let’s call monad the ego, to say the moi, with its appurtenances.[11] The notion of appurtenance, we see what he means. For example, “I perceive the table,” is an appurtenance of the ego, that’s fine. I am used to perceiving the table; it’s an appurtenance of the ego. We see what he means. But this is already rather interesting since – I’m speaking for those who know a minimum, but most among you know a minimum of phenomenology — the intentionalities, the consciousnesses of something are the appurtenances of the ego. [Pause] And in a very odd text, Husserl goes so far that he says: these are immanent transcendences. The intentionalities are transcendences, transcendences of consciousness toward things, but these are immanent transcendences since these intentionalities are immanent to the monad. The monad is the ego grasped with all its appurtenances. And all intentionalities are appurtenances. You see!

And there you have Husserl asking a very strange question: how do we pass from immanent transcendence to objective transcendence? [Pause] That is, is there a way for the monad, as it were, to get out of itself? You recall the fate of the monad? We are fully within something of such great importance for Leibniz: without doors or windows. There is no way for it to get out by itself. At first glance, there’s just no way. How could one get out of oneself if there are neither doors nor windows? [Pause]

And here we have Husserl who relates a story and says: it’s odd because the ego in its appurtenance, that is, the monad, grasps among its appurtenances one very special appurtenance. It’s something that it identifies as the other, [Pause] that is, it identifies it as a lived body, the lived body of the other. [Pause] That’s a very odd intentionality, a special intentionality, why? Because it’s an empty intentionality. I’ve got a lot of empty intentionalities: for example, I look at that whatsit, that apparatus, but I have empty intentionalities; it’s the side that I don’t see. Only it’s an empty intentionality, but were I to make a little effort, if that interested me, it would fulfill itself. So that’s fine. Whereas when, [Pause] in my appurtenances, I run into one of you, and it’s an empty intentionality; in what sense? In this sense, [that] whatever I do, I would not be in your place and you will be yourself. I discover something in the appurtenances of my monad, a lived body, which can only connect with another monad. You see?

And perhaps it’s that, if you recall Being and Nothingness, you remember a really beautiful page by Sartre in which we do see that Sartre was inspired completely by Husserl and by this very text by Husserl, while still making it seem, and not only making it seem, but in reproducing it. This is when Sartre imagines himself or sees himself in a public garden, he’s looking at flowers, and there he sees someone who is looking at them at the same time. And he explains, in a very beautiful page, that it was as if it was his entire world that was leaking, and since he loves miserablist metaphors, this was a world leaking through a sewer hole. You see? He was centered on his world, all that, and then he sees his neighbor looking at the same thing. It’s as if his whole world was drained, was drained into the other’s direction. He is no longer the center of his world.

What do I find of interest in that? In both cases, the living body [Pause] is really like the kind of line that creates passage from one domain to the other. [Pause] Could we say that the father of all this is Leibniz? Alas, no! Alas, no! But I am not sure that it’s not he who is right. For you to have in hand all the elements of the problem, what I believe is that, on the contrary, Leibniz would tell us something like: very well, yes, in the monad’s appurtenances, there is still something that is odd, it’s that never ever can one get out. And I believe… — Here I must have the texts as well as a lot of time; I’m just giving an indication. — I believe one would find texts not going all the way to saying — I am not forcing him to say this – but [texts] circling around the following idea: there would only be monads if there were no animals, if there were no living beings. It’s vitalism that removes him from spiritualism. [Pause]

I return to Richard [Pinhas’s] question,[12] this why I was telling you that, in my opinion, he [Leibniz] is the inventor of animal psychology: he needs animals. And he explicitly says it often. He says explicitly: those who believe that there are only monads and what is inherent to monads, and what is included in monads, can only believe in human souls. It’s finally the animals (bêtes) that force us to some extent to agree that there are bodies. [Pause] He would not say, as Husserl did, he would not say that this is the existence of the other (l’existence d’autrui), for a simple reason, as we will see. It’s that in closed monads, there is no encounter with the other (autrui). We have to explain the encounter with the other (autrui). Already it can only occur outside monads. He [Leibniz] cannot suggest it. Besides I am not even sure that, in Cartesian Meditations, Husserl could suggest the encounter with… He doesn’t say the encounter with the other (autrui), but the encounter with the lived body of the other (autrui). It seems to me that this exceeds the power of perceptions contained in monads. So, he cannot suggest it, or at least, a genesis would be necessary. As he says in the text, it’s very beautiful, for those that this might interest, this text, as he speaks about a genesis, he indeed says: it’s a question of creating a genesis, in this fifth meditation. I believe that he does not yet have enough data to create a genesis of the lived body.

But see why I am lingering over this. I would like to have you sense something: it’s that the entire morality of the event has these two coordinates: on one hand, be worthy of what happens to you, and on the other hand, learn to inscribe it into your flesh. [Pause] One must not, one must not… [Pause] It is even necessary sometimes, it’s necessary that everything acts. What are civilizations? Each civilization offers us manners of inscribing into the flesh; each civilization offers us manners of being worthy or not. So it’s very complicated.

Take a case that fascinates me: the jester. The jester is a fundamental personage. There have been lots of studies of the jester; very interesting, the jester. At first glance, take the Russian jester, or else the English jester. I mean that you can look from Shakespeare to Dostoyevsky, and I have forgotten some. At first glance, the jester is someone who, when something happens to him, is unworthy, and deliberately is unworthy [of the event], and then avoids inscribing it into his flesh; it flees in all directions. And then, in a more complex manner, we always learn that it was the jester who was the only one to inscribe in his flesh and to be worthy of what happened. There are all sorts of stories about this.

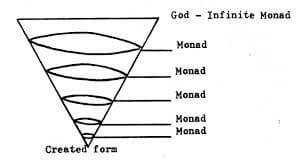

But finally, I am saying, we could… [Deleuze goes to the board] We do it like this.[13] See, we could draw a line that would begin by being straight, horizontal, and then we would have it bifurcate into two, like this, like a little branch, you see? We would put “event” on the straight line. Then, on the upper bifurcation, we would put “virtual”. Fine, I’d be happy to do it, but is this clear? We’d put “virtual”. On the lower bifurcation, what would we put? We would put “possible”, and then we would place there a huge bubble with “actual” written on it; this would be the monad.[14] The monad includes the virtual world, it actualizes it; it is actual. So, on the other hand, we would put “possible”, and we would not place a bubble there, and we will see what we would have to put… We would place some gadget, [Laughter] and this time, it would be: “real,” with a mistake we must not make: the one that would seem to say that it’s matter that’s real. No, it’s not matter that’s real, but matter acquires the reality that it can, or that corresponds to it, when a realizing thing, about which we know ahead of time that it concerns the lived body, [Pause] incarnates within matter. Matter takes some reality when it incarnates the event. So, I cannot say it better. Good, this is fine. [Pause] You see?

I have the feeling that, in Leibniz, these aspects are why there are two floors; this is why there are two floors. The two floors is the circuit of the event, and yet you sense in advance that there will never be the least direct rapport between soul and body. The two floors will always remain separate. I say simply: the realizing thing will perhaps be that which causes passage from one to the other, that which makes the aspect of the event pass from one to the other. The realizing thing, once again, is a notion that only appears entirely at the end of Leibniz’s works, in his final years. Before, he is satisfied with invoking, how to say this, a correspondence between the two floors, the upper floor and the lower floor. Entirely at the very end, he arrives at something very profound: it is not enough for the event to actualize itself in the monads; it must realize itself in the body. That [insight] was not yet in his earlier philosophy. There is a correspondence between the two, and what realizes in the body is a realizing thing that will explain the rapport of the monad and the lived body. [Pause]*

So, as a result, at the very end entirely, we would have three aspects from Leibniz: the soul and the folds in the soul; the folds in the soul are the events that are expressed in the soul, the soul and the folds in the soul. Matter and the pleats in matter, [Pause] this in which the event realizes itself. And between the two, assuring the realization, [is] the realizing thing that can no longer be either monad, or lived body, but that can only be one thing: that which brings the lived body to the monad. It will be the rapport of the folds in the soul with the pleats of matter, and that corresponds to the Latin name: le vinculum subtantialae. The vinculum, what is it? It’s the chain, it’s the knot, it’s the chain. What is this chain? Is a chain necessary there so that the two kinds of folds correspond to each other? Why [offer] this chain at the last moment? Is it this that will decide on textures of matter, but also qualities of the soul? We are going to be thrown into an entire philosophy that will therefore confirm for us that not only are there folds in the soul, pleats of matter, but [that] a vinculum has to be made to intervene, one that, if it were possible, would sew them to each other. It doesn’t sew them to each other, in fact, but it sews a lived body in a special way, a living body that is the body of the monad. All this we have to look at more closely.[15]

But I am saying, this is not for you to understand because if I addressed myself to your understanding, I believe that this would be very obscure; it’s so that you feel something. Here I believe that Leibniz makes us feel something and that I really had to try as well to make you feel: it’s a conception of the event. It’s as if I told you, well fine, what do you want an event to be other than something that makes us stand up straight, or else that makes us lie down, something that calls out to a [kind of] dignity, and that has nothing to do with “let us be worthy because of others, someone watching me.” And also it’s something that creates a wound (fait une plaie) – but a wound, I am wrong in saying wound, that’s even grotesque — or [something] that scratches. There are caresses (chatouillements) of events, and that’s perhaps the best ones. There’s all that: that it concerns your body in that form! And that it concerns your soul in that form!

And this is very difficult. I mean, everything always has its little brother as an abominable misunderstanding (contresens). “Be worthy of the event”, well, that can be an odious sentence. It’s precisely because we have to agree on the word “worthy” (digne). I imagine that someone might have just suffered an important loss, not a loss of money, but a very important human loss. You tap him on the back and tell him: “Be worthy of the event.” I hope that he would haul back and smack me a few times. What does dignity mean? Here, I cannot say more about it; it’s for each of you to [answer] if you pose the problem like that. One also has to scratch at one’s body. Scratch at oneself, what does that means? One has to be a louse (un pouilleux) of the event. [Laughter] And how does one scratch at oneself? There are hideous manners of scratching at oneself: “Oh, I’m the most unfortunate.” And every morning, I offer myself some scratching, “to me, the most unfortunate!” And then, in fact, there are hideous ways of scratching oneself. This is something else entirely. I am not the most unfortunate. But, finally, there’s no sure formula (pas de recette) for this. So, I am telling you, fine, this is one point.

There’s nothing [else]? … Any reactions, any…? It’s not that I am demanding any at all. No reactions? You sense where I am going with this, it’s all fine! Having a lived body, having a living body, fine. Being a monad, having a living body: there you see that being a monad is no more than half of ourselves: we must have a living body! [Pause] Yes? [Interruption of the recording, text from WebDeleuze] [1:05:01]

Georges Comtesse: I remember in a text by Leibniz that he was talking about what you were suggesting, the vinculum. He takes the example of hearing (l’audition), starting from a sound source, hearing an echo. [Return to the BNF recording]

Part 3

Deleuze: Because he is… This is very odd because, in my opinion, there are two texts. The vinculum is a term coming very late in Leibniz’s work. So, you only find it in texts entirely at the end, and notably, in my view, I am not even sure that it exists elsewhere than in the correspondence with Des Bosses. That’s one point. But, a second point, there are in the Letters to Arnauld, much earlier; there is, in the Letters to Arnauld, an extraordinary text in which he imagines the conditions of an orchestra in which all the different parts would not be visible and where – he doesn’t use the word vinculum since he doesn’t know it, or finally, he is not using it for his own purposes – he already uses the word echo. In this, your recall is perfectly correct. But there, to my knowledge, we owe it in great measure — because the text is in the correspondence to Des Bosses when he says that the vinculum is an echo, it’s from texts of very, very great difficulty — and to my knowledge, it’s [Yvon] Belaval who was able to provide commentary in such a way that we experience no difficulty, and you very aptly retained it; what you are saying is very faithful to Leibniz, but it corresponds to the interpretation by [Belaval].[16]

It’s even obvious what you are saying. Let’s suppose — I am simplifying enormously — there are four sound sources. Assimilate them into monads. Fine. There are four. Assign four notes; the notes are perceptions that you can assimilate to the monads. What is an echo? That’s what is wonderful in an echo, that it is second; it assumes there are sound sources. Only what is the miracle of an echo? As Comtesse said, he [Leibniz] implies, let us assume, for example, a wall. What effect does the wall have? It is going to constitute the unity of the four sources by echo; they had no unity. You will tell me: they might have unity if it was four notes taken out of a particular piece of music; it was four notes. The miracle of the echo, as Leibniz tells us, is to introduce a secondary unity. But this secondary unity is going to be essential since it’s through it that he is going to explain the vinculum, that he’s going to explain this kind of stitching (couture) of the living body. The stitching of the living body will be an echo. And you see why he will need that: what creates the unity of the lived body, of the living body? There suddenly, he forces me to go faster, but the faster one goes, the better it will be. [Pause]

What can create the unity of the living body? Monads are spirits, they are without doors or windows, they are one by one. There are no monads of monads, you see? [Pause] There indeed has to be something equivalent to the wall in order that from a plurality, from a multiplicity of monads results a unity, a secondary unity: the unity of the lived body will be that of the vinculum, that is, of the wall. You will ask me, where does the wall come from? What is this wall? We will see. It’s a secondary unity; it’s a unity of stitching, and that’s what is going to be constitutive of the lived body. Otherwise, for the lived body, there would be no unity; there would be neither lived nor living body. So, if you will, Comtesse’s intervention is all the better as it allows those who wish it to create the unity with this kind of grouping of problems: Leibniz, Husserl, and even Sartre, once it’s been said that Leibniz… Husserl explicitly refers to it; it would be somewhat arbitrary if there weren’t this explicit reference in the fifth Meditation. [Pause] Yes, is this ok?

So then, we tell ourselves, a genesis is necessary, yes indeed. You see our problem: a genesis is necessary. In the end, this is what I insist on – what a shame we aren’t ending with this because I wasn’t insisting on anything else – these are the two aspects of the event. [Pause] At that point, there would be practical examinations (épreuves pratiques): lessons on a topic, written questions: Does the real virtual (virtuel réel) exist? [Pause] Second question: is the actual indeed possible? (est-ce qu’il y a de l’actuel possible ?)

It’s very embarrassing. Look, if you read the commentators on Leibniz, it’s very embarassing: possible, virtual, actual, real, are used by them in any old way, I believe, well not by all of them. It’s really annoying if they use [these terms] any old way. Once again, you have your two very different lines. It’s as if we were confusing the two floors. [Pause] Some possible realizes itself, but it’s always, when some possible realizes itself in Leibniz, look at the context. Obviously, you will always find examples that don’t go in this direction, but that doesn’t matter. When some possible realizes itself, it’s always in some world of matter, some body. [Pause] When some virtual actualizes itself, it’s always in a soul. [Pause]

So now we grasp fully the two floors, and we’d say that a weaving is needed between the two, a knot, a vinculum, so that what? It’s your choice! So that the lower floor might exist, so that the existing lower floor might have any rapport whatsoever with the upper floor. In the end, there will be lots of answers.

In a sense, that would give us an ending. I was telling you, at the start of the year, I was telling you: yes, you know, the Baroque, we are going act as if we grasped a definition, and then we will see quite well where that leads us. And I was telling you that the Baroque is not making folds because we always make folds, everyone has always been making them. It’s that [in the Baroque] folds might extend to infinity. And on this [point], what is fine, otherwise nothing matters, [is] I was, I was a bit, how to say this, one can’t just do any old thing when one is too completely sure of oneself. So I wasn’t sure that this would work all the way to the end.

And then, really, several days ago I stumbled on some catalogues of El Greco: it’s frightening, it’s frightening, it’s frightening. It’s frightening not only due to its beauty, but what does this beauty of El Greco mean? Of course, everything is not of the same value; of course, all the paintings do not have that same kind of expression (formule). He created – fine, I cannot place it – he created seven or eight “Christ in the Garden of Olives”. There is one in England, in London that is so strange because, and I cite this because it’s the proof of our hypothesis, everything in it is folds, there are only folds, that’s all there is! And the folds are distributed over three registers: [Pause] folds of fabric, and it’s not in the sense in which every fabric then makes folds! If you look at a reproduction of this painting, so it’s Christ’s tunic in which the folds are so developed, pleats reconnecting into each other. It’s a fantastic study of folds. Folds of boulders; the boulder is in painting perhaps what is folded as much as cloth. The boulder-folding! And to this he adds a treatment of clouds that is a veritable fold, cloud-folding. There is voluntarily a manner of treating the clouds, just as he treated the boulders in a certain form, and in the entire painting, there is this circulation of three sorts of fold that truly connects to infinity.[17]

Now that we are reaching the end, I would say to you: well yeah, what are we doing? It’s this story of the folds of the soul. Once again, the folds in the soul, that comes from the event being included in the monad. [Pause] And then there are the pleats of matter. And between the two, what is there? There is this stitching, this vinculum substantialae that arises there, just before [Leibniz’s] death, and that is going then to confer — suddenly I ask myself if I would stop as quickly as I was thinking… it matters little — which is going to confer textures on matter, for we will have to consider – us, I mean; there are people who have already done so — the textures of matter. Leibniz uses the word, he uses the word “textura”, also at the end of his life. He must have had so many ideas. There are these textures of matter, which normally ought to belong to a Physics of matter, and to an Aesthetics of matter after all. An Aesthetics of textures, there is no more difficult a notion, in my opinion, it’s so much more beautiful – it’s not in order to attack the notion of “structure,” but I tell myself that anyway, it’s been quite a few years that we’ve been talking about structure so much. It’s not that there was anything too wrong with that, we did … quite well. But what if we gave ourselves a bit of a break in order to go towards some other notions that have remained…

“Texture” is an extremely difficult notion to analyze. I am speaking for you; at your age, or in your research projects, I would say that if it happened to some among you: look also at the richness of the material regarding textures. I mean, there is “industrial material”, very good for the moment; be competitive, but one of the least studied materials, and perhaps the most important, is painting. The great painters of textures are not at all unknowns (pas n’importe qui), and one would find that these are kinds of modern Baroques. I don’t know myself, one has to see if, among the great Baroque painters, there is already what might be recognized really as radical textures. – [Deleuze speaks directly to one of the students] This was for you, if you can take that on a bit more than you already have, since you have already begun to … — I see three great modern painters of textures; it’s up to you to go see [for yourself], and I am certainly forgetting some: [Jean] Fautrier; [Jean] Dubuffet who rightfully recognized his debt to Fautrier since Dubuffet constantly uses the word structure; and Paul Klee. It’s nonetheless not by chance that they have something in common and that they are not completely unknown to one another.

I was saying that [Deleuze coughs forcefully] because we find ourselves facing… In the end, what brings the folds of the soul into the pleats of matter and the pleats of matter into the folds of the soul? At the same time, that bothers me because we had wagered that all of this might hold together without stitching. [Laughter] And there we are perhaps needing some stitching, the stitching passing through the living body, without which the inorganic body would not be a real body, would purely be an imaginary body, and without which the monad, closed in on itself, etc., could not connect with anything else. [Pause] A break, ok? Five minute break? But I beg you not to come back after fifteen minutes. [Break in class and in the recording, then return] [1:22:09]*

Deleuze: … for our, for our requirement … [Pause] Yes?

A student: On Christ. Is Christ a monad who says: I am incarnate, me, am I incarnate? Does this in a certain manner realize the incarnation of a monad? Would Christianity or Christ himself be a specific event?

Deleuze: There we have it. That’s not difficult; I will answer quickly because the more a question is “fundamental”, the more one must answer quickly. [Laughter] Above all, one must not say, but that’s not important because it wasn’t what you had in mind, but it was in the way you formed what you said; above all, one must not identify monad with event. The event is what happens and what occurs. The monad is what contains what happens and what occurs. The event is crossing the Rubicon, the monad is Caesar. And it’s, above all, on the one hand, the monad-event distinction that we always need to make. Second point: the monad is never incarnate. There is no incarnation of the monad for one simple reason: the monad suffices fully and entirely to itself without doors or windows. When we say, to move quickly, that the monad has a body, this means that in the domain of bodies, something carries over into a particular monad.

So if Christ is incarnate, he is incarnate exactly as all monads are incarnate. This is even no doubt the model of incarnation. Does Christ pose particular problems? Yes! But strangely not at the level of incarnation, in Leibniz. He posed some very particular problems on the level of transubstantiation. And transubstantiation is not incarnation; it’s trans-carnation where the body and blood of Christ become bread and wine. You see? So he poses a special problem in the sense of passage from one body to another, the passage from Christ’s body to the bread and body.

Having said this, personally Leibniz is Protestant and does not believe in the transubstantiation, but he agrees to give some help to reverend Des Bosses who is greatly concerned about this topic, and he [Leibniz] tells Des Bosses – it’s at a rather lively moment in the correspondence with reverend Des Bosses – if I were you (this is not my problem, not my business), but if I were you, I would say something like this, something like that, and he give one of Leibniz’s strangest interpretations of transubstantiation that ought to delight everyone, and that must have been useful no doubt to certain Catholics because reverend Des Bosses seems rather quite happy. In any case, as concerns Christ and incarnation, to my knowledge, he has no special position except that that he is certainly the archetype or model of incarnation.

So, I am saying let’s start over on our genesis. But you remember that I had already demanded this the last time: above all, don’t get it backwards, although one is constantly tempted to get it backwards. You recall this genesis that consists of: starting form the monad, the monad contains everything, it expresses the entire world. It expresses the entire universe. Only careful: it has a small, privileged region that it expresses specially or clearly. We saw this. Here, I’d say, is the first proposition. Second proposition: so I have a body. That’s what we have to understand. So I have a body. [Pause] In fact, this could not be otherwise. It might be more convenient perhaps to say: I have a body, so I express a privileged region! The only thing that is certain is that the privileged region, my little subdivision that I express clearly, once it’s said that I express the entire world, but I express it obscurely and in a confused way.

Sense already everything that we won’t have time to do. You foresee that there are all kinds of monads in Leibniz, that there are some very different statuses of monads. For example, a butterfly does not connect to a monad like you or me. There is a whole hierarchy of monads. There is a grand hierarchy of monads. So one has to wonder: are there monads that express nothing clearly, that don’t have a special region? In this, the texts are very difficult, [and] one would have to undertake some very close readings of these texts. Leibniz varies according to the occasions. According to the occasions, he suggests that certain monads remain in complete darkness. There are others that, for a certain period of time, express a tiny clear region. In my opinion, animals have a monad that expresses necessarily a tiny clear region. For example, a cow expresses clearly its field. [Pause] Only, from the fact that it expresses its field clearly, it expresses closer and closer the surrounding world, the entire universe. Even a cow has a clear zone of expression, and if we transport it to another field, it changes its clear expression. So this is already not that easy. But, so even for animals.

And in other texts, Leibniz seems to tell us that it’s only reasonable souls that have a clear zone of expression. This isn’t possible. [Pause] This would raise for us some… But I am saying, your clear zone of expression is what concerns your body, and with this, we don’t have the time. There are numerous texts, in the Letters to Arnauld notably. I cite page 215, in the excerpts selected by Madame Prenant: “I had said that the soul, naturally expressing the entire universe in a certain sense, and according to the rapport that the other bodies have with one’s own” — and according to the relation that other bodies have to one’s own. That’s what defines my clear region: everything that affects my body, in fact. And in a certain way, that indeed must pass through my body. And you see, I cannot say, first of all, I express clearly what passes through my body, and second of all, the monad. Why? Because what is first is the monad without doors or windows. Why does it have a clear region of expression? Because it has a certain number of singularities around which it is constituted. Consequently, I am saying [Interruption of the WebDeleuze text; transcript follows the recording] everything that it expresses clearly concerns my body and affects my body and passes through my body.

Only, that’s not easy. They have to state immediately their objection: but my body, I don’t know it at all. If I treat it like perception in the monad, well, this is a singularly confused perception. You remember? I express the universe in a confused way; let’s accept this. If there is my body in the universe, I express my body, agreed, but I express it in a confused way, in a dim way (obscurément). The movements of my lymph: this is what Arnauld objects. Arnauld objects, well, you grasp the movements of your lymph, And the movements of your blood, you grasp them very, very dimly, in a very confused way. How can you say that you express clearly what concerns your body and what passes through your body when, in fact, you don’t express your body at all clearly? Look, this first … You express everything, agreed, but you express everything in the dark. This is the dark depth of the monad. We have seen it. You express everything in confusion. So you express your heartbeats, your arteries, the movement of your blood, all that. You can always say that you express it, but you express it in a very, very confused way, and then you are going to tell us, on the other hand, that what you express clearly when you say, “Ah, there, this is green grass,” that even a bull or a cow have done? They say, there it is, it’s green grass, and there it [the cow] has finally expressed something clearly. And it’s because it doesn’t pass through its body, how do we deal with that? And I believe this to be one of the most astonishing things from Des Bosses-Leibniz.

And a second problem – that was a first problem – a second problem is: in what way isn’t having a body [Pause] simply a perception? In what way is the body an object of perception? What makes me not say “I perceive my body” as I perceive green, predicate of the monad? But I say moreover, I say that I have a body, [Pause] and not the monad, but me, I am composed [Pause] of a monad and a lived body. [Return to the WebDeleuze transcript] What allows me to affirm the body as object of perception? And on these two points, on these two problems, I must say that Leibniz’s answers are astonishing. I would just like to give them to you so that you might reflect on them.

First answer: what explains that the body, that I only grasp confusedly, that my body can be said at the same time to be the condition through which [Pause] is transmitted to me (se rapporte à moi), through which passes everything that is transmitted to me, everything that I express clearly, the small portion that I express clearly? I am trying to relate this to you because… You will find in Leibniz all kinds of texts saying, generally, this: there are tiny unconscious perceptions, and with these tiny unconscious perceptions, we create a conscious perception. [Pause] Moreover, that’s what the meaning of the organs is. And some examples that he willingly gives are: you don’t hear the sound of a drop of water if it’s far away, you don’t even hear the sound of a far-off wave, and then you hear something, little by little the wave [comes] closer, the wave is like that, it tells a tale like everyone; the wave is close, until it becomes a conscious perception: the sound of the sea. Or again he says: you don’t hear what each person is saying in the crowd, but you hear the brouhaha. [Pause] There are lots of texts by Leibniz going in this direction. And we’d like to interpret them in the sense of part-whole.[18] Oh well yes, it’s very simple: one doesn’t perceive the parts, but one perceives the whole.

Or else that reminds us of something in psychophysics. And a psychologist, at the time of my baccalauréat [roughly, high school finals] was extremely annoying, named [Gustav] Fechner. He was trying to establish a rapport between the increase of excitation and the emergence of sensation. It’s that the bachot (baccalauréat) is always a terrible thing, since Fechner is a nineteenth-century philosopher who is quite remarkable. And he has as a remarkable trait to be Leibnizian, so this is why it’s less astounding that he’d be the author of psychophysics. Moreover, far from being a positivist scholar, as we are made to believe in psychophysics — it’s not a compliment — I would say that he’s a kind of grandiose madman (fou grandiose), a very great German Romantic. So it’s rather strange that a great Romantic attracted to German Romanticisms, or perhaps to post-Romanticism, it’s very strange that he created this discipline, but in the end, this matters little.[19]

If you look at the texts, I have the impression that we are going to realize something much more curious, in the end, than that. [Pause] Try to understand, it’s not hard to understand, just a bit of infinitesimal calculus, at a basic level, entirely basic. You have two quantities x and y as variables. You can submit them to increases and to decreases of any sort. We call them, for example, D small a, D small b, whatever you want. And then you can make them undergo any increases or decreases whatever. [Pause] No, rather [let’s say] D small x, D small y. And then you can make them undergo additions and subtractions, [End of the Web Deleuze transcript; the remaining transcript is from the recording] smaller than any given quantity. [Pause] We would call them, let’s say, Delta x and Delta y. [Pause] At the extreme, Delta x equals zero, Delta y equals zero. You’ll write Delta y over Delta x equals zero over zero. Is this ok? It’s not too difficult.

I’ll read you a text by Leibniz, and you’ll immediately understand. [Deleuze looks up the text] “These are not absolutely nothings” – Delta x and Delta y – “These are not absolutely nothings; they are nothings only comparatively,” that is, Delta x equals zero in relation to x; Delta y equals zero in relation to y. – You’ll correct this; I’m so tired (abruti) that if I make a… But I think that this is quite simple. – However, Delta x and Delta y are still not the same thing and are not equivalent. I’ll demonstrate this easily… Will you do it for me, go to the board? [Interruption, different movements in the room; Deleuze asks help from the students with what he wants to display on the board] Voilà. [Deleuze watches the student, Richard Pinhas, who is writing the mathematical example on the board; pause of approximately 2 minutes]

Richard Pinhas: Is that ok, what I’ve written?

Deleuze: That’s fine. You have to understand, there’s a small problem: it’s that x [Pause; Deleuze reads what’s on the board and hesitates, gives more instructions] – Place a big C… [Pinhas: Here?] and place a small c from A to C [Pinhas: A small c from A to C] and x by convention is equal to Ax [Pinhas follows the instructions while repeating them[ such that Cx equals Ax less Ac… Ok? [Pinhas: That’s good] That’s good. Everything is fine. [Pause; several students ask questions about this presentation on the board] Eh? [Deleuze provides more instruction to Pinhas; someone asks: But where is it, the big X?] Obviously, you cannot see it [probably hidden at the bottom of the board where a student is sitting]; this is going to end up badly like that other time. [Laughter]

Good. Let’s look at the minimum, ok? Do you want me to read the text? It’s beautiful, it’s quite beautiful. This will give you an idea of mathematical style of… [Deleuze does not read the text, but continues to have corrections made on the board] Be open solely to this: the line Cy, and E, capital E, [Deleuze indicates the board] E and Cy are transported in parallel to themselves toward A. What’s happening? E tends toward zero, C tends toward zero. There we are. This is the whole mystery that you must understand. You have to understand that both of them tend toward zero, but they never become equal. Why? Because if they became equal, it would be necessary to, to what? It would be necessary that y, little y, the side A, little y, and the big Cy – are we giving it a name, the big Cy? – become equal as well. And, when you’ve obtained the coincidence in A, you’ve maintained your triangle, A-x-y, with its difference between x, that is, between Ax, and Ey. So, C and E can coincide with A without losing their relation of the kind, so we’ll call it a kind, let’s say, differential rapport, Delta y over Delta x. Is this ok? Is it ok more or less?

Here’s what I am suggesting for you when you read these texts by Leibniz about the sea, etc. In the end, it’s not at all a question of the whole-part problem. What is it about? It’s about conditions in which a differential rapport has occurred in a way to produce something, [Pause] in a way to produce, we must add almost, indirectly. [Pause] Delta y over Delta x, you assimilate them to what? I need to have two terms. What’s going to be annoying in reading these texts by Leibniz is if I only hold onto one term, water. But I must have two terms, otherwise that makes no sense. I need to have “water” and “the ear”. [Pause] You have to consider the differential of water, let’s say, the… — in these texts, it’s deliberate, it’s not even science; it’s the way that, if you will, we can make a kind of mathematical allusion – you have to consider the differential of water, let’s say, the drop, the smallest drop, [Pause] and the differential of the ear in such a way that the whole text ought to be rewritten under the form Delta y over Delta x. [Pause] What are we told from differential calculus in the, in the most elementary way?… [Interruption of the recording] [1:51:27]

Part 4

… So, that works, and I insist on this greatly because I am struck by… Here I believe that the interpretations are going, generally that they are going… [Pause; Deleuze doesn’t complete the sentence] I consider a different example, the eye. It’s the same thing, eh? I am looking at my field, I have a Delta x that is [Pause] grass, some grass, a tiny bit of grass, the smallest bit of grass. I have a Delta y, the tiniest, the tiniest glance, [Pause] Delta y over Delta x. – No, I cannot rightly say green; I am saying green grass. I withdraw the green; I especially haven’t said green… I didn’t say it? [The student near Deleuze recites: A tiny bit of grass] Ah, that’s it, I’m ok, the tiny bit of grass, and then my glance from the eye – Delta y over Delta x, no matter the conditions – here, in certain conditions, you can invent them biologically… I’m rather close, I’m rather close, I am awake, all that – Delta y over Delta x equals, equals what? The green, a green patch in the monad, a perception of green. This is an entire theory of perception.[20] You’ll tell me that matter really must act. No, not at all, for the moment, not at all. [Pause] You have some matter, there, you’re going to have it; we’ll see, you’re going to have it. You have a body, you have a body.

What I am in the process of explaining is how the most confused thing in the world is able to give you, or to communicate to the monad, a clear perception. With Delta y over Delta x, or rather to Delta y over Delta x corresponds – I’m saying nothing more than “corresponds” – a perception included in the monad: it’s some green. – [As in the previous session, the sound of a squeaking door is heard] What is that? [A student near Deleuze: It’s the door] [Laughter] – I’d say that it’s a causality, it’s a causality, but a very odd one. It’s a causality between terms that don’t need to have anything whatsoever in common, what Leibniz would call an ideal causality. [Pause] I would explain the perception of green through Delta y over Delta x, of two bodily elements, the bit of grass, the glance from the eye.

Second argument, also very strange, a completely different argument: I am returning to my beaten dog or to the pin that is stuck when I am a poor little baby drinking his milk, the pin that my nursemaid cruelly sticks in me. [Laughter] So then, I feel a pain. However, Leibniz says, it’s odd because this pain does not resemble [Pause] the pin’s movement. [Pause] And there’s no doubt, right? [Pause] Likewise, the pain of the dog receiving the blow from the stick does not resemble the striking stick.

So I’d almost like, I’d like to take you as witness. There are two extraordinary texts, in my view, extraordinary texts by Leibniz. — I think I’ve lost them so that… Aïe, aïe, aïe, aïe, aïe, aïe, aïe, aïe… I really better not have… [Pause; Deleuze looks through his texts] No, it’s not that one… [Deleuze keeps looking for the texts] It doesn’t matter because I have it elsewhere, but I don’t have… [Pause] And not here either… But I am going to find it, you know. It does exist. [Pause] [A groan of frustration from Deleuze]… Ha, ha! There it is!

So, in all this, I’ve completely lost my effect because I no longer recall… [Laughter] [Pause] Here we are… [Pause; Deleuze continues to look in the text] I am trying to cut the text because I’m not managing… [Pause][21] “And although it is true that their entire explication is beyond our forces” – he is saying, look, already to explain all that is really outside our strength – “because of the too great multitude of enveloped varieties, we are no less penetrated more and more by experiences that make us discover the bases of distinct thoughts of which light and colors provide us with examples. These confused feelings” – colors and light – “are not arbitrary” – these are perceptions, right, in the monads – “These confused feelings are not arbitrary, and we do not agree with the received opinion today of several people and supported by our author” – this about [John] Locke – “that there are no resemblances or rapports between our sensations and corporeal traces.” This is indeed our problem: there is a resemblance between the sensations in the monad and the corporeal traces of the body, in the body.

“It seems rather that our feelings represent them and express them perfectly. Someone will perhaps say that the feeling of heat does not resemble movement” — Someone will perhaps say that the feeling of heat does not resemble movement – “Yes! No doubt. It does not resemble a sensible movement such as that of a carriage wheel. But it resembles the assemblage of a thousand tiny movements of fire and organs that are its cause. Similarly, whiteness does not resemble a spherical convex mirror” — [Pause] whiteness does not resemble a spherical convex mirror – “However, it is nothing other than the assemblage of quantities of tiny convex mirrors such as we see in the foam by looking at it closely.” But he says an astonishing thing; he says one thing: you never find a resemblance between perception and the perceived object if you keep yourself within the limits of the fixed. If you pass on to the infinitesimal, you will then find yourself before white as sensation and an infinity of tiny convex mirrors. What is the resemblance of both? Foam. [Pause]

The other text, you’re going to see its… I only know two of them by Leibniz. It’s New Essays on Human Understanding, book 1. [Pause] He says this: before me, you know, philosophers have distinguished two kinds of qualities, primary qualities and secondary qualities. The primary qualities are extension, etc.; the secondary qualities are sensible qualities. And they said, at the extreme, primary qualities resemble the object, but secondary qualities are subjective like color, heat, and nothing corresponds to them in the object, at least nothing direct. And here is what he says in this text of the New Essays:

“I just noted how there is a resemblance or exact rapport regarding secondary qualities as well as regarding primary qualities.” For him, a resemblance has to go all the way there. This is enormous if you see what he means, what he is in the process of doing. One must master the confused insofar as it’s confused, if he finds a resemblance. If he finds a law of resemblance through the confused itself, well it’s a fantastic plus for him. “It is indeed reasonable that the effect responds to its cause; and how does one guarantee the opposite since we don’t know at all distinctly either the sensation of blue, for example, or the movements that produce it?” Hence the text that I wanted to reach: “It is true that pain does not resemble the movements of a pin” – the same thing, you recall; the other text said, it’s true that white does not resemble a convex mirror — “It is true that pain does not resemble the movements of a pin, but it can resemble quite well the movements that this pin causes in our body.”

This, I’d tell you… This is a text that doesn’t seem like much. What is he doing? I am commenting on a phrase: “It is true that pain does not resemble the movements of a pin,” which is not in the finest conditions of a proof. If I have a chance, I am not going to establish a term to term rapport, movement of the pin [to] pain, “but it can resemble quite well the movements that this pin causes in our body.” There, I have two terms, and furthermore, two terms that pass, that tend toward the infinitely small. As my wicked nursemaid moved the pin toward my body, this was a finite movement, but there, when she presses it into my poor body and turns it, [Laughter] you see, there I find myself faced with two corporeal factors. I find myself in the presence of a Delta y and a Delta x, and it’s this Delta y and this Delta x to which pain corresponds in the monad. And likewise for the white: as long as I was trying to place into connection [Pause] [The student near Deleuze tells him: Mirror] convex mirror [to] white, this was stupid. What I had to do was place into connection, on one hand, a material rapport, infinitely tiny mirrors and foam as physical phenomena, and it’s to this Delta y over Delta x rapport that will correspond the white in the soul. In both cases, you have pain in the soul equals Delta y over Delta x in the body, [Pause] and I believe that this is the only way to interpret these texts, in any case, these two great, these two great texts by Leibniz, in such a condition, I am saying, what it is that makes me have a body.

There we are. So I can summarize in order to finish. I have a body. Why do I have a body ? It’s a consequence, nothing else than a consequence. I have a body because that results – this is a genetic point of view – that results from me having a clear region of expression. We especially must not reverse the causality. It’s the body that results from my clear region and not the reverse.

Second statute of the genesis: [Pause] Why am I sure about having a body? [Pause] Because what I express clearly in my monad corresponds to my body, because what I express clearly in my monad corresponds to something of the Delta y over Delta x kind, [Pause] which is like the ideal cause or the object, and the resembling object of my perception. So there is a resembling object of my perception, so there is an ideal cause of my perception, and it’s not only my body, but the rapport of my body to all other bodies. We find ourselves henceforth faced with two kinds of rapport, a rapport of bodies between one another to infinity, a rapport of monads between one another to infinity. This is not the same type of rapport, for a simple reason: it’s that bodies exert a direct causality on each other, whereas monads do nothing other than inter-express themselves, that is, express a one and same world, each one being without doors or windows.

There we have it; this is what I wanted… The next time, you’ll tell me if… and then we will draw some new conclusions, and we will begin the story of harmony. You sense why we have reached harmony: it’s because, between all these operations of the body and all these operations of monads, there has to be something that implicates itself as harmony.

A student: Can you give us the references for the two texts [by Leibniz]?

Deleuze: Eh, New Essays, book 1… Yes, in fact, for me, these two Leibniz texts are essential. Eh, book 2, New Essays, chapter 8, and the other, [Pause; Deleuze looks in his text and consults the student next to him] in the Guérard edition, eh? Volume 4, [Pause; noises of students leaving] page 575, and the title is… [Pause] Eh, the title is complicated because… [Pause] That [reference] depends on if you have another edition… [Pause] This belongs [Pause] to texts among a whole group entitled “Explication of the new system concerning the union of the soul and the body”, and this precise text is “Addition to the explication.” [End of the recording] [2:14:11]

Notes