November 12, 1985

How can this be a method? It’s a method — it seems to me very rich — because this method of visibilities can found a whole area of aesthetic analyses. We saw that it’s the same for architecture…architecture is a regime for the distribution of light. There are regimes of light, there are regimes of visibility, exactly as there are regimes of statements. What is a prison ? It is a regime of visibility. What is an asylum, a hospital? It is a regime of visibility. Think about it, it’s frightful…. Power is perpetually that by means of which we are seen and we are spoken about.

Seminar Introduction

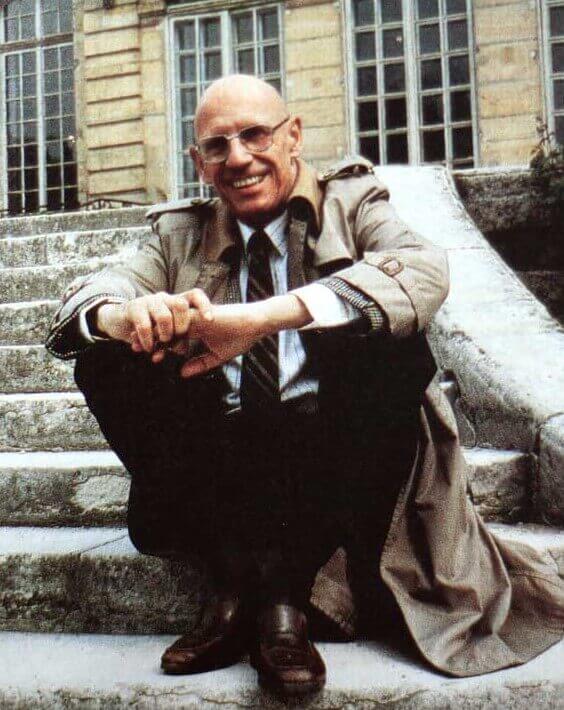

After Michel Foucault’s death from AIDS on June 25, 1984, Deleuze decided to devote an entire year of his seminar to a study of Foucault’s writings. Deleuze analyses in detail what he took to be the three “axes” of Foucault’s thought: knowledge, power, and subjectivation. Parts of the seminar contributed to the publication of Deleuze’s book Foucault (Paris: Minuit, 1986), which subsequently appeared in an English translation by Seán Hand (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

Having previously considered the flip side of the question “what is a statement?” by examining visibilities, Deleuze insists on the importance of determining the corpus of knowledge, the criteria resting in power which is thus immanent to knowledge. So Foucault seeks the sites of power and of resistance to power in the 19th century, with experience always conditioned and gridded by power relations. Such relations are discussed, says Deleuze, in Foucault’s essay “The Lives of Infamous Men” (La vie des hommes infâmes), after which, in Foucault’s last books, he seeks to “cross the line”. Remaining within this reflection on knowledge-power through the constitution of one’s corpus, Deleuze also reflects on how Foucault examined visibilities, how for Foucault, the “one sees” is light while the “one speaks” is language. Exploring how these distinctions emerge in The Birth of the Clinic, Deleuze then pursues them with examples from different regimes of visibility, notably figures of light for the painters Robert Delaunay and Paul Cézanne. Deleuze then delineates four levels of difference between statements and the group of words, sentences and propositions: first, the inherent mixture of systems in speech; second, the necessary choice to be made within this multiplicity, with Foucault’s own position regarding the subject being that statements have no author, but an “author function”, also emphasizing the example of free indirect discourse as a means of short-circuiting subject positions. Deleuze indicates that the statement refers to variable subject positions, all ordered according to a “one speaks”. As the session ends, Deleuze indicates a third level, within the proposition, referring to a state of affairs to which he will return in the next session.

Download

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Foucault, 1985-1986

Part I: Knowledge (Historical Formations)

Lecture 04, 12 November 1985

Transcribed by Annabelle Dufourcq; time stamp and supplementary revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Translated by Mary Beth Mader; additional revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Part 1

. . . to think [or: has thought] of Foucault. This point amounts to asking: but what is it, exactly, that he calls a statement? So then, my task, at the close of this effort, my task is to try to give an answer, an answer—and, here, you must press me if this answer is not clear and concrete. Because the question is indeed: what is a statement, insofar as a statement is not to be confused with words, sentences, or propositions.

So, on this point, you’ve got to be very severe. If I don’t give an answer, well, you’ll have to say: that won’t work, all that! In exchange for which . . . I’ll permit myself to go very slowly, that is, to take the detours that seem necessary to me, because, once again, it’s a question that seems complicated to me. And Archaeology of Knowledge is assuredly a difficult book. So, I permit myself certain detours, notably in order to answer a question that one of you asks me. And this question, I’ll read it so that you can retain it, and I think one can in fact ask it.

This is the question: “One can think [about] things without there being any visibility; there is no co-implication between the two,” says the person who asks the question. “On the other hand, one cannot think [about] words unless statements exist.” All that seems uncertain to me, okay, I’m trying to . . . – “even if their primary source is a ‘one,’ one cannot say that words are not statements, and thus the cause of statements would be statements themselves.” You see: I’m focusing minimally on this part of the question: one can speak of things independently of visibility, one cannot speak of words independently of statements. In my view, no, it wouldn’t work, if this were the view. But it’s complicated to try to get clear amid all of this. So, our fundamental question—still under the heading of “but what does ‘knowledge’ mean?”—is this sub-question: “but what does ‘statement’ mean?” And all we know to orient ourselves is that the statement, once again, is neither a word, nor a sentence, nor a proposition. Okay, so, where were we on this?

Here’s where, last time, I sensed the need to start with a detour, supposing that perhaps the other half, the other side of the question, namely, the question of visibility, could shed some light for us on the main question concerning the statement. And last time, we were about at this point. I was saying: you see, we’ve reached the point where, as for the story of the statement, Foucault’s method consists in saying: when you set out a problem, whatever problem it is, give yourself a corpus. You start from a corpus. A well-defined corpus, depending on the problem that you set for yourself, depending on the research you are conducting. You see, at this level, he does not grant himself the statement—that would be very, very vexing, there would be a vicious circle. He does not grant himself the statement, it’s a corpus of words, sentences, and propositions. Only they are no longer simply words, sentences, and propositions, since they are words, sentences, and propositions grasped insofar as they form a corpus. So, that’s already a first step in his method. The subjacent question arises from this—we saw it last time—“but how does one constitute the corpus?” How does once constitute the corpus? Try to understand how this question is, already, a very complicated one. For if I must start by constituting a corpus in order to manage to understand what [a] knowledge [un savoir] is, then the means I use to constitute the corpus must not presuppose anything from [a] knowledge [un savoir]. Otherwise, the method wouldn’t work.

In fact, from the start my problem has been: “what is knowledge?” And I say, for example, “to know is to state.” Okay, how are statements to be found? I start off from a corpus of words, sentences, and propositions. Here, an objection: “How do you constitute the corpus?” If in constituting a corpus, I appeal to anything that presupposes [a] knowledge, that won’t work. [Pause] As a result, in Foucault’s early books, you will not find any rules by which he constitutes his corpuses. You won’t find them. Furthermore, he goes so far as to say: Oh, me, I only make fictions, my corpuses are fictions. Which amounts to saying: I am a sort of novelist.

So, he’s not wrong. At the same time, we know very well that it is not true and that, right from his early books, he already had an idea that he would not develop until later. But what is this idea? If I then take the subsequent books, the answer explodes, and for us it is at least provisionally satisfactory, even if we will study it directly later this year. But if I already refer to this answer, these criteria for the constitution of the corpus, once we specify that these criteria must not be drawn from [a] knowledge, from what then will they be drawn? They will be drawn from power. That is, once a problem is given, I constitute the corresponding corpus by determining the sites of power put into play by the problem. Whence Foucault’s idea, which he had from the start, but which he will not explicate until much later, namely: power is strictly immanent to knowledge.

What’s the concrete result of this? We’ve already seen. He wants to constitute, for example, a corpus of sexuality, that is, a corpus of words, sentences, and propositions of sexuality in the period under consideration. How does he constitute the corpus? The answer is very simple: let us determine the sites of power put into play by sexuality at a given point in time, for instance, in the 19th century. What are sites of power “and of resistance to power,” put into play by sexuality at a given point in time? Well, he’ll tell us: ecclesiastical power, not in general, but particularly in the confession; the power of the schools, not in general, but particularly in boarding school rules; juridical power, on the level of expert witnesses, not in general, but with respect to psychiatric expert witnesses about perversions, etc. I can, in any case, set out a finite number of sites of power around which sites, around each of which sites, are formed circles of words, sentences, proposition. That’s how I constitute a corpus. Good.

But you see that this opens up for us, although we have just barely broached the question “what is knowledge?”, this opens future questions up for us. What are these questions, above all? I can already indicate them, and then set them aside right away, since to move on to them I would already have had to settle the question: “what is knowledge?” They are: what actually are these centers of power? And, especially, why does Foucault break with phenomenology, from the start, by telling us all the time that “there is no wild experience, there is no free experience?” It’s because experience is always conditioned and gridded by power relations. And, finally, wild experience would be the experience we have, of centers of power when they question us, that is, the opposite of a wild experience, of a free experience. And also: whence Foucault’s doubt, Foucault’s melancholy, when he says: well, yes, people will say—he loved raising objections to himself, it’s always better to raise one’s own objections, since those from others, it’s . . .—so, he used to say: but people will say to me—in other words, “I’m objecting to myself”—“your thing’s no good, you’re not making it across the line,” he said. “You’re still staying on the side of power.”

But, my God, but my God, how he did not stay on the side of power! But, in his thought, did he stay on the side of power? In the sense that power relations, sites of power, are there to determine the corpuses. And in a very beautiful text, drawn here, as always, from this article, “The Lives of Infamous Men,” [“La vie des hommes infâmes”],[1] about which I spoke to you a bit last time, he says: “People will say to me” [Deleuze laughs], “people will say to me: ‘Here you are again, always with the same inability to cross the line, to cross over to the other side, to hear and to make heard the language that comes from elsewhere or from below; you always make the same choice, from the side of power, of what it says or what it causes to be said.’” And I believe that one of the reasons for Foucault’s long silence, there are many reasons, between History of Sexuality, Volume I and The Use of Pleasure, at least one reason, is this problem that became more and more pressing for him, namely: How to cross over to the other side? How to cross the line? Isn’t there something still beyond lines of power, and how does one reach them?

But, for the time being—we’ll see how this problem is set out and resolved by Foucault—but for the time being, we, we can be fully satisfied with this first answer. We are not yet asking the question of power, since we are in the midst of the question of knowledge, and we’re merely saying: oh, well, right, his corpus of words, sentences, and propositions, in fact he sticks to the conditions of his wager, he can form it without presupposing in any way what is in question, that is, “what is knowledge?” Because he forms the corpus of words, sentences, and propositions depending on the sites of power and resistance in operation, implicated by the corresponding problem. You set out a problem, for example: what is going on with sexuality in the 19th century? You form your corpus, without a vicious circle, to the extent that you ask: what are the words, sentences, and propositions that orbit around the sites of power implicated by sexuality or that concern themselves with sexuality? This is clear, right? It’s very important for what is to come, for us, since it shows a certain relation, a certain presupposing of power by knowledge.

So, once you have your corpus, what do you do? [corpus] that is highly varied, and you see that it gains its unity on this basis: it is the corpus of sexuality. What happens? [Deleuze considers the drawing on the board] Well, from this corpus, what do you induce? We saw this the last few times, something one can call by various names: a ‘there is,’ the ‘there is of language,’ or else—it amounts to the same thing—a ‘one speaks,’ or else—it amounts to the same thing—a language-being, a being of language. But what is this? This is an empty generality—‘one speaks,’ ‘there is language,’ a language-being. In what way is this linked to the corpus? How does one derive it from the corpus? It’s not complicated, you’ll recall, this is the result of the last sessions. It’s not a matter of a universal, it’s that language-being, the ‘one speaks,’ is inseparable from a given historical mode that it takes on in relation to a given formation. It is inseparable from its historical modality.

In other words, it is this ‘one speaks,’ this ‘there is language,’ this language-being, it is a way in which language gathers in a given formation. And in fact . . . So, “in a given formation,” that is, the way in which the language gathers . . . can I say in the 19th century? Yes, at a pinch, I can say: language gathers in a certain way in the 19th century. But it’s a large, a very large gathering: language-being in the 19th century or the ‘one speaks’ in the 19th century. It’s really a very vast gathering. Understand that in fact there is a gathering of language for each corpus. Each corpus effects a certain gathering of the whole language. And, in fact, the corpus of sexuality effects a certain gathering of the whole language around sexuality. And so much so that each corpus effects a gathering and each corpus refers to a language-being, to a ‘there is language.’ Only, I can speak of a ‘there is language’ proper to a whole historical formation to the extent that the historical formation is defined in relation to these corpuses, in relation to the whole of these corpuses. So, at that point, there will be a great gathering of [the] language that will correspond to the language of the period or of the formation. Okay. Are you still alright? Interrupt me if something isn’t right, because it’s got to . . . [Deleuze does not finish the sentence]

So, I would say . . . statements . . . here [pause; he writes and draws on the blackboard], it’s as if statements are at the intersection—that’s this dotted line—they are as if at the intersection of the corpus of words, sentences, and propositions, and the language-gathering on the corpus. Or else, in the book on Raymond Roussel, Foucault will tell us: to find statements, you have to break open or open up, one must break open, open up, words, sentences, and propositions. And what opens up words, sentences, and propositions? The ‘there is language.’ The ‘there is language,’ the gathering of language on the corpus that forces the corpus to open up and to release statements, which it would otherwise keep enclosed within. Okay.

But all this is metaphors, right? “Break open, open up,” okay, so, if I’m at my dotted line, like so, I’ve got the diagram for the statement, but I have to fill in the interval. [Deleuze indicates the blackboard drawing] Between the gathering of language and the corpus on which it gathers, that’s where the statement emerges. This still does not tell us what a statement is, but it will compel us to spell it out. There you have it. Time for break: I need to make a detour . . . [Interruption of the recording] [20:55]

Part 2

. . . pole of knowledge as essential as statements, I have no choice, I must find a result or configuration that is analogous in the case of the visible. Yet, it is certain that Foucault conducts the analysis directly for the statement and does this much less so for visibility. But this wouldn’t be the first time that the paths are so complicated that, right at the point where he seems not to move on to absolutely necessary analyses, it’s in fact there that a little clarity shows up for us. Since . . . what’s going on for visibilities? I would say: well, you know, it’s the same thing. It’s the same thing. You’d like to know what is visible at a certain period. We saw this theme. At a given period, there are things that can be seen and, when they can be seen, they are seen; there are others that cannot.

If, once again, the 17th century put the mad, vagabonds, and the unemployed in the same place, it’s not because it saw no difference, it’s because it sees a resemblance that will stop being perceptible in other periods. What resemblance? That’s what visibility will be. [Pause] If you’d like to know what a visibility is, you have to start from a corpus as well. It won’t be the same corpus. In this case, it will no longer be a corpus of words, sentences, and propositions—what’ll it be? It will be a corpus of objects, of things, of states of things, and of sensible qualities. You’ll perhaps understand immediately that what is at issue is that, in just the same way that statements . . . in the same way as for statements, we knew it, we did not know what they were. But we knew one thing: if statements have a sense, they refuse to be reduced to words, sentences, or propositions; they’re not the same thing. We do not know what visibilities are, but we know that if they exist, they refuse to be reduced to things, objects, states of things, or sensible qualities.

As a result, I start from a corpus of objects, things, etc. and in so doing, I presuppose nothing about what is to be found, namely: “what is a visibility?” I start off from a corpus, a corpus of things, states of things, sensible qualities at a given period. It could be an architectural corpus, among others. There will always be some architectures in my corpus. Or if I’m interested in painting, I start from a corpus constituted by this or that painting. I’m not going to discuss—just as it is false that the linguist discusses language in general, the linguist always starts from a determinate corpus—well, an art critic doesn’t discuss painting in the 17th century in general. The critic always starts from a determinate corpus, that is, a determinate set of paintings, and surely, the results would not be the same had another corpus been selected.

In any case, we have the same problem we had earlier: yes, but how do I constitute this corpus? In my view, Foucault’s answer—an implicit answer, but precisely, it can be . . .—the implicit answer will be the same as for the corpus of sentences, namely: I rely on sites of power and resistance at work in the problem I’m examining. What does this mean with respect to painting in the 17th century? It has to mean something if I am correct in this reading of Foucault, it has to mean something. And so, yes, for example, I see that in the 17th century—here I’m saying hugely banal and commonplace things—I see that in the 17th century at least an entire corpus of paintings can be defined as “portraiture.” Portraiture. I can think: okay, the second half of the 19th century sees a return to portraiture, notably with [Vincent] Van Gogh and [Paul] Gauguin. You don’t need to know much about painting to know that portraiture for Van Gogh and Gauguin is not part of the same corpus as portraiture for the 17th century painters, and thus that portraiture in general, portrait painting, does not form one corpus; it’s astride numerous corpuses.

What is at issue in the corpus of “17th century portraiture?” Among other things—I’m not saying “solely”—power relations, immediately. Which power relations? Power relations between painters and their models. What is the model in the 17th century? It is above all the lord, or better still, the king. What is [Diego] Velásquez’s Las Meninas, in the famous commentary that Foucault will derive from it? What’s happening there? What’s happening is that there’s a painting that shows us a facing view, as it were, of the royal family, and the painter who is looking at something, or someone, which we can’t see. We only see the painter’s gaze, and everything that everyone in the painting is looking at, as a reflection in the mirror at the back of the painting. And what everyone was looking at was the royal person, who, we can see this in the mirror, is looking at those who are looking at him. In other words, an exchange of looks, yes, but on the basis of a relation of powers: the power of the painter and the power of the king. Very well. So, it seems to me that at this level Foucault’s own analyses confirm that the corpus I will constitute is indeed determined on the basis of the sites of power at work in the problem that is posited. For example, “what is a portrait in the 17th century?” Okay. So, I have my corpus that I can call architectural, pictorial, whatever you want. Good.

Thus, until now, the parallelism between my two series, the statement and visibility, is verified. What do I do, once I have my corpus? Once I have my corpus . . . It’s possible that my corpus is just a single painting. It could be ten paintings. It could be the conjunction architecture-painting. You see, it could at the extreme be the corpus for the century, or the corpus of the historical formation. And so, once I have my corpus, I set up . . . I do the same thing, I set up my vertical line and I ask the question: what gathers in the corpus, on the corpus? It was not hard, earlier: what gathered on the corpus of words, sentences, and propositions was language-being in or as such-and-such a mode. Now, here, what gathers on the corpus, on the physical corpus of things, states of things, qualities, etc.? Well, it seems to me that Foucault’s answer was—I would say as much—“there is light.” Or else—but this won’t be easy to understand, or on the contrary, perhaps it will be, I don’t know—or else “one sees.” Or else “light-being,” the gathering of the whole of light on the corpus. Okay. What does that mean? It means that ultimately a painting is a figure of light. What is primary is light. No, at this point it’s not a matter of knowing whether it’s true, not true, etc. It’s a matter of knowing to what extent this idea is important and interesting. A bad idea is an idea of no interest. A good idea is an important and interesting idea.

So, okay. I understand what this means: but, of course, a table gathers, in a particular mode, in its mode, all the light of the world—it does not divide light, light is indivisible . . .—it gathers, in such-and-such a mode, all the light of the world. Exactly like a corpus of words, sentences, and propositions gathers in its own particular mode, all the language of the world.

What is primary is light. What does that mean? That means: do not think that light is a physical medium [un milieu physique]. Light is not a physical medium . . . that is, light is not Newtonian. Light is no more a physical medium than—it is also a physical medium, but, for example, light as a physical medium is called “secondary light”—light is something more than this. What is it? Well, it is indeed what Goethe and not Newton intended, namely: it is an indivisible, it is a condition, it’s a condition for experience and of the medium. It is an indivisible condition. It is what philosophers call an a priori. Mediums develop or are extended in light. Light is not a medium. Light is an a priori condition, that is—this originates with Goethe, against Newton—what can be divided is a secondary light. Primary light is an indivisible. It falls on the corpus of things, states of things, and qualities; exactly as the whole of language, language-being, fell on the corpus of words, sentences, and propositions. Light is not divisible: it falls. And, in falling, it captures that on which it falls. What is primary in painting is light; it is primary in relation to lines, primary in relation to colors. Colors and lines derive from light and not the reverse. A painting is first a tracing of light [un tracé de lumière].

You’ll ask me: but why does he say that? Why does he say that? Well, that’s what he says. So. It’s up to you to find out whether it suits you or not. If it does not suit you, then no matter. No matter. Try and grasp that it’s ridiculous to think: but, really, is it true or not? That makes no sense, because he is proposing an analysis in which he extracts a condition in relation to something that is conditioned. For his part, he has the sense, let’s suppose before a painting, for example, he has the sense that light plays the role of condition in relation to lines and colors. Can one make a theory as interesting as this one where color would be the light? It’s a stupid question: you’d have to actually create it. You’d have to create it, and then we’ll see. What? Is it a question of taste? No, it’s not a question of taste. It’s not by chance that some of us will feel compelled to say: no, it’s not light that’s primary.

So, then, everything is of the same value? No, not at all, everything is not the same value. You’d have to actually create it. So then: at the point where we now are, we in particular, what interests us? We can see well, and in what sense, that for Foucault a painting is above all a tracing of light. It’s not solid lines; in painting, the line [le trait] is a solid line. [Pause] Beyond solid lines, or rather, as a condition for all solid lines, there are lines of light. And lines of light are not solid lines painted in yellow. Indeed, for example, in Velásquez’s painting, Foucault gives us a description on page 11 [in The Order of Things],[2] a description, at one point, in terms of light: “the groove in the wall from which the light is pouring….” So, for the figure of light, here’s what he tells us: “This spiral shell presents us with the entire circle of representation: the gaze” — the gaze of the painter upon the canvas – “the gaze, the palette, and the brush, the canvas” — of which we see only the back — “the paintings, the reflections”, — etc. etc. . . . We can see only the frames, and the light that is flooding the pictures from the outside, but that they, in return, must reconstitute in their own kind, as though it were coming from elsewhere, passing through their dark wooden frames. And we do, in fact, see this light on the painting, apparently welling out from the crack of the frame; and from there it moves over to touch the brow, the cheekbones, the eyes, the gaze of the painter, who is holding the palette in one hand and in the other a fine brush . . . And so, the spiral is closed, or rather, by means of that light, is opened.”

We can see clearly the lines of light, these are not the solid lines drawn by the painter. They’re truly the condition that lays out the painting as a field—as a field of what? As a field of visibility. In other words, just as the ‘there is’ of language was an a priori, but an historical a priori, since it was the condition in relation to a particular corpus or to a particular historical formation, so the ‘there is’ of light is an historical a priori. Light in the 17th century, that is, the way in which light gathers, either in 17th century painting, or in 17th century portraits, or even in a single case, the way in which all the light in the world gathers in Velázquez’s Las Meninas. Such that visibilities will be exactly what I just said for statements. This will be the dotted line that opens up. To find the visibilities one must break things open, one must open qualities up. Visibilities are neither things, nor qualities. Well, then, what are they? They are what emerges when the corpus of things and qualities meets light-being. Visibilities are lines of light.

Okay. But, put differently, visibilities are not first defined as acts of a seeing subject, nor as the givens of a visual organ.[3] Especially not! They are neither qualities, nor states of things, nor visions. The ‘one sees’ is not a vision, the ‘one sees’ is light. The ‘one’ is light, just as the ‘one’ in ‘one speaks’ is language.

But then why call these visibilities? Because of “light.” Because they are given by light, by light as indivisible. And in as much as they are given by light, then, yes, they are related to sight, but they are related to sight only because they are given by light. Even more: it’s through light that they are related to sight. In other words, you see, they are related to sight only secondarily. Visibilities are related to sight only secondarily, they are in fact related to sight by light. But from here, there’s no more stopping. It’s a chain reaction [un emballement], since if visibilities are related to sight only secondarily, they do not relate to sight, or rather they are not related to sight without also being related to the other senses. To the ear, to touch, etc. Such that visibilities, far from being givens of the visual organ—what are they? They are complexes that are multi-sensorial, optical, auditory, tactile . . . But why call them “visibilities?” In fact, they are complexes of actions and reactions, multi-sensorial complexes of actions and reactions, of actions and passions. Why call these “visibilities?” They are visibilities insofar as these complexes exist only to the extent that they come [in]to [the] light. They do not exist as long as the light does not draw them to itself, as long as the light does not make them come. [Pause]

Oh, really? But does Foucault actually say that? That’s all very well, but does he say that? You understand? Visibilities are called visibilities because they find their condition in light, as indivisible, as an indivisible element—not at all Newton, but Goethe. Thus, visibilities are related to sight only secondarily and, to the extent that light relates them to sight, light does not relate them to sight without also relating them to the other senses. Does he say this? Yes, he says it. Yes, yes, yes. He says it, and in a very odd passage in Birth of the Clinic, where, there, the example he gives is no longer aesthetic or artistic, but epistemological. It concerns what happens in pathological anatomy and he tells us that, I’ll read the passage . . . It’s about the new methods introduced by [René] Laennec. And you know that Laennec is famous for, among other things, having introduced tactile and auditory data [des données] into medicine, into diagnostics. A percussion of illnesses and an auscultation of illnesses. And here’s how Foucault reads this: “When Corvisart” – he’s another physician of the period — “hears a heart that functions badly” –so, that’s auditory – “when Laënnec a high-pitched voice that trembles, what they see . . . is a hypertrophy, a discharge.”[4] “When Corvisart hears a heart that functions badly or Laënnec a high-pitched voice that trembles, what they see with that gaze that secretly haunts their hearing and, beyond it, animates it, is a hypertrophy, a discharge.”

“[T]hat gaze that secretly haunts their hearing …” That is: this gaze, this ‘one sees,’ is in fact not a gaze. It’s a light-being that draws to the light not only what is seen, but likewise what is heard and touched. This question of “coming [in]to [the] light” is not a question of space. When Corvisart hears a heart that functions poorly, there is something that comes to light. What? Hypertrophy. “[W]ith that gaze that secretly haunts their hearing and, beyond it, animates it,” and Foucault continues: “Thus, from the discovery of pathological anatomy, the medical gaze is duplicated: there is a local, circumscribed gaze”—that’s the ‘I see.’ There is a gaze that is I see, with my eye. “[T]here is a local, circumscribed gaze, the borderline gaze of touch and hearing.” The gaze of the ‘I see’ in fact is what my eye sees, which borders on what I sense, what I hear; it’s a “borderline gaze of touch and hearing, which covers only one of the sensorial fields.” Which covers only one of the sensorial fields, one among others: there is the optical field, but there is the auditory field, there is the tactile field, etc. One among others.

Foucault says as much: that’s only the first gaze, or rather, we should say, it’s only the secondary gaze, since this secondary gaze is conditioned—but in the same way as the other sensorial fields are—by a primary gaze. The primary gaze does not condition the secondary gaze without also conditioning the other sensorial fields, that is: it conditions the secondary gaze in its relations with the other fields. And in fact, Foucault tells us: “But there is an absolute gaze . . .” In fact, it’s not a gaze, it’s light-being . . . “[T]here is [also] an absolute, absolutely integrating gaze that dominates and founds all perceptual experiences. It is this gaze that structures into a sovereign unity that which belongs to a lower level of the eye, the ear, and the sense of touch.” The term ‘absolute gaze’ is plainly not a felicitous one . . . on the contrary, it is in fact very felicitous: one must replace it with light-being. It’s the same thing. The absolute gaze is light.

For those who were here in the other years, you’ll perhaps recall that in [Henri] Bergson there is a very similar theme: light is in things, the gaze is in things. “[T]here is [also] an absolute . . . gaze”—that is, a light-being —“that dominates and founds all perceptual experiences.” It’s also very close to Heidegger, you know, it’s the Lichtung. And in [Martin] Heidegger’s case the lineage with Goethe is immediate. But I believe no less in a lineage, in a lineage in the case of Foucault, a direct lineage to Goethe on the theme of light as an indivisible condition.

And he continues: “When the doctor observes, with all his senses being open, another eye . . .” When the physician observes with his eyes, but also when he percusses with his fingers, when he listens with his ears . . . “When the doctor observes, with all his senses open, another eye is directed upon the fundamental visibility of things . . .” What does “the fundamental visibility of things” mean? It means when things are no longer there as things, when things are broken open and they release pure visibilities. And what are pure visibilities? It’s the relation of things, states of things, and qualities with primary light as indivisible condition. At that point, visibilities emerge. When primary light falls on things, then things break open, they are shucked, they open up. They open up so that what can emerge? Pure visibility that rises [in]to the light. And this pure visibility, surely, will be related to the eye, but it will not be related to the eye without also being related to the other senses. So, all this is very good. This is all very good!

Whatever does this mean? This time, consider another thinker who happens also to be a painter himself. I talked about him in other years: [Robert] Delaunay. How is Delaunay also close to Goethe? It’s very simple. Delaunay, it’s not what he says. What does he make us see? He has an idea, a painter’s idea. His painter’s idea is very simple. It’s hard to do in painting, but it’s simple to say, namely: figures are not first solid, what is primary are figures of light. That is, visibility is the figure related to light. At that point, it’s no longer a solid figure. Light, too, is an indivisible condition, and what is this indivisible condition? The production of luminous figures. Light produces figures that belong to it.

You see: light is no longer composed, as it is for Newton. That’s the big distinction between the Newtonians and the Goetheans. Light is an indivisible condition and hence is productive; it produces figures that belong only to it. In other words, light is movement, light is production. Consequently, one must not confuse the things that move and the movements of light. Nor must one confuse the lines of things and the lines of light. Neither must one confuse the figure of the thing when light meets it with the very figures of light that light forms at the surface of things. And what is the painter’s task, for Delaunay? To break things open, to open states of things to reveal the pure figures of light. And what will this revelation be? It will be the figures for which Delaunay is famous: the circles, the half-circles, the helixes—with the great division: there are lunar figures and solar figures. The Moon is no less a light than the Sun, so that, ultimately, it’s a split condition. Light is an invisible condition: yes, but it has at least two sides: solar and lunar. Okay, and Delaunay’s luminous helixes, the circles, Delaunay’s luminous semi-circles, will affirm their primacy over both solid lines and colors. Colors are born of light, lines are born of light. What is primary is visibility, that is, the figure of light.

And Delaunay had an admirable remark, that explains his whole project, it was a witticism, sometimes it’s the witticisms … He was settling a score with Cubism, with the Cubists, and he said: you see, what is [Paul] Cézanne’s contribution to painting? He was terrific, Delaunay, he saw very clearly, he said, Cézanne’s fundamental contribution to painting is to have broken the fruit bowl. It’s nice, because to break the fruit bowl is to break things open.

Cézanne, in the 19th century, broke things open. Undoubtedly, the Impressionists had prepared the way, but, no, they had not broken things open in their materiality. They created a play of reflections, it was a very particular regime of light: they made reflections play across things. But as for Cézanne, he broke the fruit bowl. That is, he breaks open, he shatters the thing in its materiality. And he says: there’s no point in trying to glue it back together. Cubists are like guys — that works out fine for them, but in a certain way it’s right — he says: they’re guys who are constantly trying to glue the fruit bowl back together, but who go wrong. They put a piece that doesn’t go with another piece that doesn’t go, and they think they’ve glued it back together. And they actually have glued it back together. But you shouldn’t glue back together what Cézanne had broken. On the contrary, what should have been done was to take the direction Cézanne took, that is, to the new figures make emerge that Cézanne had made possible, that is, pure visibilities. There you have it.

So, I’m saying, okay, understand that I’m not trying to push Foucault toward points that he did not develop. That’s why, I would say, to answer your question: no, visibilities are not at all . . . there is no . . . it’s exactly like statements. Just as statements imply language, all things, in fact, imply visibilities: all you need to do is break them; in fact, they must be broken. The corpus is there only so that visibilities emerge, and visibilities are not givens [des données] of sight. They are related to sight, even more—I forgot—in the text I was reading to you, on 167,[5] he uses a very strange word: “In any case, the absolute limit and the ground of [all] perceptual exploration are always limned by the clear plane of an at least virtual visibility.” Do you see why “virtual visibility?” Because visibility is related really, actually, to sight only by the intermediary of light—which does not relate it to sight without relating it to the other senses.

Okay, so you see. What do you see? You see . . . I’ll tell you: how can this be a method? It’s a method, it seems to me very rich, because this method of visibilities can found a whole area of aesthetic analyses. Because we saw that it’s the same for architectures. To understand an architecture, one has to break open, one must see. It must be understood as: architecture is a regime for the distribution of light. There are regimes of light, there are regimes of visibility, exactly as there are regimes of statements. Before seeing in it . . . again, as I told you, a prison is what? It’s a regime of visibility. An asylum, a hospital, is what? It’s a regime of visibility. Think about it, it’s even frightful, and this is how, this is how it’s so tied to power, and why Foucault was so very, very aware that . . . power is perpetually that by means of which we are seen and spoken about. Power speaks us and power sights us.

When do you know you’re in the hospital? You know you’re in the hospital when, instead of the full door of your bedroom, you see that disturbing door through which you are seen. You know, with the three little bars, there, the three little bars where . . . and then you’re pretty sure that the door doesn’t close, that is, that the head monitor, as one says in both hospitals and schools, that the head monitor can come in at any moment. Awful! Awful! I won’t even discuss prisons: we saw that they are made for that, that is, their whole stone architecture is made so they operate, so that the prisoners can be seen without themselves seeing, and that those who see them cannot be seen.

You may say: if you propose this kind of an equation, I would say: this is an equation of visibility. How to solve the equation? With stones, that is, with things and states of things. But what you will have incarnated with stones, that’s your equation, that is, pure visibility. I’m saying: the prisoners must be seen without seeing, the guards must see without being seen. And, yes, this is what I would call a virtual visibility, a distribution of seeing and being seen. What actualizes it, what realizes this virtual visibility? There’s a perfectly simply answer: it’s stones, it’s a disposition of stones. A disposition of raw materials . . . A disposition of raw materials, which are materials you can touch, feel, hear, listen to, listen to the sound they make, etc. What is all this? It’s simply the actualization of the figure of light. You see, Foucault goes much farther than saying: there is one sense that has primacy. He does not at all say: sight has primacy over all the other senses. He tells us something much more profound. He says: light, as condition for sight, does not relate the visible to sight without also relating the visible to the other senses. It’s a primacy of light, it’s not a primacy of one sense over another. This is the way in which it’s completely Goethean.

Okay, so, I’m saying: you can derive a method of aesthetic analysis from this. You can derive a method of scientific analysis from this, using scientific statements. But what complicates things is that—but we can only see this later, since we’ve seen that it will be a problem for us, so we must definitely return to this problem—these two, here, they are extremely . . . they do not have the same form, no matter how complete the parallel between them, there is an absolute difference in nature between visibilities and statements. We can come back to this problem only later. But, in any event, that doesn’t rule out—I really want to say this, even at this point, since we can work all this out clearly later on but let me nonetheless remind you—that despite the fact that there is an absolute difference in nature between the two, this does not rule out that each one constantly captures the other. That is: regimes of visibility capture statements, statement regimes capture visibilities… [Interruption of the recording] [1:06:11]

Part 3

… Literature is composed not only of statements, it is also composed of visibilities captured by statements. How may this difference between statements and captured visibilities be indicated in language? I believe strongly that, in language, statements and descriptions are different in nature. Descriptions are not statements, they are visibilities. On my side, I have some very eminent logicians, [Bertrand] Russell, for example, who in his book that founded modern logic, Principles of Mathematics [1906], already indicated the difference in nature between propositions and descriptions. And, in a certain way, modern literature also worked out to a great extent the difference in nature between . . . in an entirely other way than Russell did . . . For example, I think the nouveau roman is wholly based on a certain dualism between statements and descriptions.

With Foucault, too, in his work, there are statements, philosophical statements—but why is his body of work interspersed from one end to the other with descriptions, be it descriptions of paintings, or descriptions of things that Foucault treats as if they were paintings? For example, when he describes the prison, he describes it as if it were a painting. There is a proper function of description in Foucault’s work that cannot be reduced to the statement. Moreover, there is an author, among the great geniuses of our literature, of modern literature, there is an author who it seems to me has established the value of this, the greatest luminist, if you will. Just as there are luminists in painting, great luminists in painting—Delaunay, for instance: he’s not a colorist, he’s not a draughtsman, he’s a luminist—okay, so, there are great luminists in literature.

I believe the greatest luminist in modern literature is [William] Faulkner. If I just try to show the Faulkner example in the framework we’ve just derived, what would we get? Can it . . . A method should have many applications, should be very fertile. What’s going on in Faulkner? First, there is something frightening, frightening: namely, it calls on all the senses, all the senses, including the basest senses. They are called upon by what? By light and the variations in light depending on the hour and the season. Faulkner’s descriptions . . . if you said to me: what is the fundamental object of the description? That is, that which can only be described—anything can be described, but it can also be something other than described. But what can only be described? Light, states of light. It’s precisely because they can only be described that they are so hard to describe.

Those who know Faulkner know very well that, to my knowledge, in the history of literature no author can match him for knowing how to describe, sometimes over a number of pages, a nuance of light that falls on a group of things. And the things are seen. But visibility is not the things that are seen. For the things that are seen are also heard, smelled, etc. Obviously, all the senses are called upon in Faulkner. Things are seen, smelled, handled, fondled, etc. All the senses are worked with a certain force . . . but with all the more force given that, all together, they are drawn toward the light. Light in August, they are drawn toward the light in August. They are drawn toward the light of five o’clock in the evening. Thus, visibility emerges, thus things open up and visibility emerges. There’s no author of light like Faulkner. And this is perhaps linked to the South, to the South of the US, since that is Faulkner’s setting—I’m specifying for those who do not know Faulkner—it’s perhaps linked to the light in the South, the light of August in a Southern state. Yeah, perhaps . . . What accounts for his having this genius for light? Okay, so, what does Faulkner do? Faulkner is the one who really makes multi-sensorial things emerge, not the supposed primacy of a sense, namely sight, but pure visibility. The cruel side of visibility, its absolute rawness. And it’s this light-being that gathers in each Faulkner novel, such that it’s fair to call the Faulknerian corpus the ‘there is of light’ as it falls on all of Faulkner’s novels, or on a particular novel, or on a particular page of a novel.

And at the same time, there are Faulknerian statements. And these Faulknerian statements, everyone knows that they emerge when? When Faulkner has, as the second pole of his genius, broken up the sentences, propositions, and words by relating to a whole of language that will blend them together. And what will the statements be? Faulknerian statements will be grasped at the point where one same name refers to two different persons, or else one same person to two different names. And it’s these genealogies, of these Southern families, in Faulkner . . .

And if I may add, in order to make it all coherent—but there’s no need—and what plays out in these two corpuses, the corpus of sentences and the physical corpus? What plays out at the level of Faulknerian statements, as at the level of Faulknerian visibilities? The answer is very simple: what plays out are abominable power relations, namely: the decadence, the decadence of the South, the degeneration of these powerful, old families—everyone who has read a bit of Faulkner knows this. Sites of power that are both consuming and consumed. And all this, the entirety of these statements linked to the sites of power astir within them, what does that yield? It yields—and here I find myself amid the best-known passages in Faulkner—it yields the famous story, full of sound and fury, told by an idiot. The story told by an idiot is the ‘one speaks.’ All that needs to be added is that not only is it told by an idiot, it’s seen by a moron. And the ‘seen by a moron’ is visibility, just as the ‘told by an idiot’ is statability [l’énonçabilité]. The statement only ever has an idiot for a subject, that is, a position as the ‘one’ of ‘one speaks.’ Visibility never has for a subject anything other than a ‘one’ in ‘one sees,’ that is, a place in light-being.

Okay, very good. Good, good, good, good, so then what? Well then, we thus agree, we’ve extracted everything we could from the parallelism. Now we have to backtrack. Let’s admit that we now have a vague idea of what a visibility is, by contrast to a seen thing. That’s one more reason to go back. Now we can’t put it off any longer, we’ve got to say: what is a statement? How is a statement neither like a word, a sentence, or a proposition? We have to try. I mean, in fact we have a vague idea. Having reached this point, we have a vague idea. Statements actually are not sentences, propositions . . . but how so? How so? How so? We must not give up. As long as we’ve not got a possible answer, we must not give up. So, we’ll search. But how, alright . . . are you alright? [Deleuze laughs] I’m not asking you that out of concern for your health, I’m asking that because . . . we’ll rest, okay, a little bit. But ten minutes, alright? No more than ten minutes! What time is it? [Response: 20 to 11] … [Interruption of the recording] [1:17:00]

… Are there any questions that would mean I couldn’t go on? No questions? One small question . . . No, no questions?

A student: [Inaudible comment]

Deleuze: Yes? A little question!

The student: You alluded to light in Heidegger . . .

Deleuze: Ah, yes, yes, well, that, that comes later, a parallel with Heidegger. Because, yes, yes, so, not right now! Another question? [Laughter] No other questions?

Good, well, let’s go, then. We have to move on since there are no questions. So, listen, now: I believe—it’s in the category of ‘I believe’—so, handle that how you wish—even so, I believe one can try to assign the difference between statements, on the one hand, and the group of “words, sentences, and propositions,” on the other, to four levels. Once we’ve looked at all four, we won’t be able to take anymore—but we won’t look at them today! Four levels. There you have it. And, so, that’s it! [Laughter]

So: the first level. I’m looking for the least occasion to . . . so . . . No? No questions? [Laughter] The first level. [Pause] It’s not only logic that deals with propositions. In a certain way—take care to number my levels, okay, because otherwise . . . in a certain way linguistics deals with propositions. What is a proposition in the linguistic sense? I would say that linguistics extracts propositions starting from sentences. But what do I mean? Oh, I mean something very, very simple. I mean: a sentence is what linguists call, let’s assume, speech. Written or oral speech. But speech—you can tell right away that I’m referring to the classic linguistic distinction between language and speech [langue/parole]. Speech is always a de facto mixture [un mélange de fait], speech is a mishmash, speech is full of stuff.

A de facto mixture, what does that mean? What does it mix? It mixes very different systems. When you speak, you mix very different systems. What does ‘a system’ mean? Linguists try—and this is their primary scientific task, they say—to distinguish systems of language [langue] within speech [parole]: a system. How is a system defined? In two ways: its overall homogeneity [homogénéité d’ensemble]—that is, the homogeneity of the formation rules, its homogeneity overall—and the constancy of certain elements. Constant elements, overall homogeneity. It’s abstract.

Example: Spoken American[6] — an example that I invoke in all the greater good faith given that I do not speak it — numerous linguistic systems correspond to spoken American. Let’s consider two. What I’m saying is said constantly by linguists, but, I specify, is maintained by [Noam] Chomsky. So, if you will, from [Ferdinand de] Saussure to Chomsky, linguists tell us: scientific work on a language [langue] presupposes that one already would have extracted homogeneous and coherent systems that will be the object of scientific study. It’s not speech [parole] that can be studied scientifically, or, at least, it cannot immediately be so studied; it can be studied only afterwards. What matters at first is determining homogeneous and coherent systems.

An example: From spoken American, I take two systems. One will be called ‘Standard American,’ the other, ‘Black English’,[7] the language of Black Americans. That there are overlaps, encroachments, is not the question. One can define two systems. For example, the rules for the past participle are not the same. Okay. When I say that the linguist extracts by and he extracts propositions from sentences, I mean that he starts from a de facto mixture [un mélange de fait]—speech—and he extracts systems each of which is homogeneous and coherent. An ‘American Standard’ system, and a ‘Black English’ system, to take only two systems. It is such systems, and only such systems, that will be the object of a scientific study. The search for the constants and rules of homogeneity. Is that clear? Good.

That’s the first thing that matters to me. I would say that: a proposition in the linguistic sense is what is part of one or another system. You see that the linguistic proposition is not exactly the same as the sentence. The sentence mixes systems, the linguistic proposition belongs to a system that is definable by the homogeneity of its rules and the constancy of its elements. Okay. To me, that’s enough for now. I’m still on my first point.

To me, that’s enough for now. I seem like I’m thinking about something else entirely. I was telling you: a foundational book on statements about sexuality is the great classic by [Richard von] Krafft-Ebing: Psychopathia sexualis. For those of you who have not read it, I cannot recommend it to you too highly since in it you’ll learn the secret of all the perversions, including an extraordinary perversion, alas since fallen into obscurity, namely, the perversion of the braid cutters, [Laughter] which at one point, was a great hit in the Metro. They were base individuals who slid up behind young girls with lovely braids and cut off the braids of these young girls. And I say that because this was, when I read Krafft-Ebing, with enthusiasm and, simultaneously, the purest moral horror, [Laughter] I was stunned by the fact that Krafft-Ebing, who had seen it all, come across everything, he’s an expert witness before the courts, all that, and he maintained an imperturbable composure in the face of the vilest things, cases of sadism that will make you shudder, or else all of their masochists, all that, one can barely read it because it makes you so, so . . . it’s unbearable, or else people will exhume corpses, abominations, just horrors, horrors, horrors.

So, he’s seen everything, and then comes a moment when he cracks. Now that’s tremendous. The psychiatrist crumbles. Which goes to show that one can never say, “I can withstand anything.” He withstood everything, the disembowelments, the removal of viscera, all that, everything: you name it, and he’s perfectly fine, it’s even as if he’s recounting trivial things, all that just goes without saying for him. Then, all of a sudden, he completely loses his grip. He’s talking about the braid cutters, [Laughter] you don’t know what’s going on at all anymore, and Krafft-Ebing starts to say: such individuals—okay, I’m quoting by heart, it’s forever in my heart—such individuals are so dangerous that one must at all costs remove them and take away their freedom. For the sadists who kill, for the Sargent Bertrand who exhumes corpses, he had nothing but the cold words of the man of science. For the little girl and her braids, he crumbles. He says: this is heinous. It’s very curious, no? It’s very, very curious. Now that’s people’s thresholds.

People always have thresholds: you’ll see a terrific sadist suddenly be a masochist and then he bends back a little fingernail, and he crumbles, whereas the previous evening, he had horrific burns administered to him, it turns out that this, he couldn’t stand. I know someone—all this is an ethics course, I’m turning it into . . .—I know someone—and I understand this very well—who withstands, and due to his very occupation, he is forced to, he stands the dead, the spectacle of the dead, of death, in the saddest and most dreadful conditions. But there is one thing he can’t stand, the image of a boat going down. I don’t know whether you’ve ever seen images of boats going down, you see that often at the movies, and you think you get it, because something about it is so moving, it’s at the very edge of what’s bearable. The way a boat goes down, it’s as if what we had was a death even more terrible than any death of a person, it’s this kind of collapse, this collapsing . . . and so, right there, he cracks.

Well, the great Krafft-Ebing cracked at the sole thought that one could cut a young girl’s braids. And yet it doesn’t hurt very much . . . Anyway, that’s what we call a digression, what I just did. So, the great Krafft-Ebing, I already told you, what is a statement in Krafft-Ebing? It’s very curious, it’s a statement astride two languages. He writes in German, and in his German sentence, as soon as what he says offends modesty, he says it in Latin and in italics. To the extent that you can’t read Krafft-Ebing unless you’ve done Latin, or at least you’ll miss something. Okay, so I would say that typically Krafft-Ebing’s statements—and here I’m choosing my words carefully—Krafft-Ebing’s statements are astride two systems. I’m not saying: Krafft-Ebing speaks German at times and Latin at other times. I’m not talking about a de facto mixture, I’m talking about a combination in principle [une organisation de droit]. Krafft-Ebing’s statements constantly pass from the German system to the Latin system and from the Latin system to the German system. You’ll say: this is something of a special case. Let’s go on.

I believe that Foucault is rather close to—and since I’m not even sure that Foucault knew this author, the inverse as well—an American linguist, a specialist in what he himself termed ‘sociolinguistics,’ by the name of [William] Labov. I believe that it’s pronounced like that, I’m not sure. L A B O V, okay? Labov, yes? Labov conducted studies that seem very, very interesting to me, I say, uhm, you will understand why it seems close to Foucault, to me. He conducted studies on, for example, a young, black American who is explaining something, and Labov wonders, for example, how many times, over a short period—two minutes, for example, he’s explaining a game, for instance a very complicated black kids’ game in Harlem—he wonders how many times in two minutes the kid switches from Black English to Standard English and the reverse, with, as Labov puts it—and this is very interesting, it seems to me—with broad swathes of indiscernibility, that is, of segments of sentences that one could just as well tie to Black English as to Standard American. At times it’s one, at times it’s the other. At times, one wants to relate them to Black English, at other times to Standard American. In other words, the young black child constantly slides, that is, moves from one system to the other. He crosses over between systems [il fait une transversale de systèmes]. His statements cross over between systems. He constantly passes from one heterogeneous system to another.

If you’re following me, you must sense that we’re on to something here. I’m sticking with these two examples: Krafft-Ebing and Labov. Two very, very different examples. But think: what do you do when you speak? You constantly cross between systems. You see, even . . . if . . . this is why linguistics is nothing if it doesn’t have a pragmatics. I mean, even, I’ll take my miserable example, and make it quick: okay, I’m fed up, I start to tell a thing about the braids of . . . it’s not the same system as what I was saying before . . . I’m crossing over [je fais une transversale], as a way of gaining time, okay. Uh, or else, no! Or else I’ve got a strong pedagogical concern which means that I say to myself: they’re tired, they can’t follow well anymore. And so, I try to become lively . . . Nothing happens—but no matter. Although earlier I was referring to one homogeneous philosophical system, here I am indulging in a system, a system of tricks. Okay, okay, it’s worth what it’s worth. I crossed over . . . Good. In life, you don’t stop. You don’t stop. Okay.

What does Chomsky tell us? Chomsky says: ah, yes, but everyone knows this, he says. He says everyone knows this, that’s the situation in fact, but never was a science constituted on fact. A science must cut out its systems from the facts. Science begins only . . . Of course, when you speak, says Chomsky, you mix systems together, but science can be a science [only] of systems separated from each other. You understand? It’s somewhat like for physics: of course, perception mixes all sorts of systems, but as for scientific physics, it can be established only if it separates heterogeneous systems so as to constitute homogeneous systems. You see? That’s Chomsky’s position.

The Foucault-Labov position consists in saying: well, Chomsky understands nothing at all. He understands nothing at all. The problem is not at all one of fact. Of course, in fact one mixes. But the problem of principle [le problème de droit] is: are there in principle any homogeneous systems? Are there any homogeneous systems? Does ‘homogeneous system’ mean something in linguistics? And what if in principle there were only passages, there were only variations, there were only crossovers [transversales] between systems? Then, everything changes. Namely, what has a value in principle are no longer propositions, each one resituated within the coherent and constant, the homogeneous and constant, system—but . . what will it be? What counts is the statement. And how is the statement defined as different from the proposition? Every statement is the actual passing [passage en acte] from one system to another, as opposed to propositions which, for their part, belong to a given system.

Krafft-Ebing’s statements are the set of rules according to which he constantly passes, in the same sentence, from a German segment to a Latin segment. The statements of the young, black American child from Harlem are the set of rules by means of which he constantly passes from a segment of Standard English to a segment of Black English, and the reverse. In other words, the rules for a statement are the rules of variation. The statement is the linguistic instance [l’instance linguistique] that comprises variations, that is, transitions [passages] from one system to another. The statement is thus opposed to the proposition. And there will be no statement unless there is a transition [passage] from one system to another system that is heterogeneous to it. Which amounts to saying—and here you’ll recognize Foucault—which amounts to saying that the statement is not a structure, the statement is a multiplicity. By ‘structure,’ we mean the determination of a homogeneous system in relation to its constants. By ‘multiplicity,’ we mean the totality of the transitions [passages] and rules for passing [règles de passage] from one system to another system which is heterogeneous to it. However, there are no homogeneous systems, there are only transitions [passages] between heterogeneous systems.

Thus, if you wish to extract—here, this is very concrete—if you wish to extract the statement that corresponds to a sentence, here’s what you have to do: do not look for the linguistic propositions that correspond to the sentence, but do something else altogether: determine which transition [passage] from one system to another the sentence carries out, in both directions, and how many times it does so. It’s at that point that you’ll have a statement. Not only do statements come by the multiplicity, but each statement itself is a multiplicity. There is no structure, there are only multiplicities.

So, to me, that’s enough for the first level, I wouldn’t ask for more; I don’t know whether you’d like more, I could try to say more, but this seems to me already to be something very, very practical, which shows the extent to which what he calls a statement has no match in the propositions that linguists study. A linguistic proposition is by nature defined by its belonging to a homogeneous system defined by constants. A statement is exactly the opposite. Thus, we are all Krafft-Ebings, even if we speak neither German nor Latin, since we are constantly transitioning [de passer] . . . You’ll say: but in the case of Krafft-Ebing, it’s very simple, it’s for reasons of modesty, that is, reasons which have nothing to do with language. And that’s indeed what a linguist would say, but that’s idiotic! That’s completely idiotic. Because you can always attribute reasons of modesty to what is external to language, but they’re also variables of the language. It’s insofar as he speaks, and it’s insofar as he produces statements, that Krafft-Ebing composes them out of German and Latin. Moreover, this is the case for us all, we are always astride several languages. That’s good: we are all bilingual. And even further: we are multilingual, it’s just that we don’t know it. You’ll say that I’m using language in an illegitimate way: not at all, I’m using it in the strictest sense: a homogeneous system defined by constants. Phew. There you go, a first point that’s very clear. No questions? No question, no question.

The second level. And here, it’s obvious, there is a choice to be made. I mean, you can’t hold both at once, you can’t say: on a certain level, it’s the linguists who are right, and on another level, it’s the multiplicity. No, you can’t do that. You can’t hold the two positions. You can’t hold the two positions. If you believe in multiplicities, there is only one thing you can say, which is: each segment of what you say, no matter how small it is, each linguistic segment, is a transition [passage] between two heterogeneous systems. Never will you find any segment whatsoever that belongs only to one system. Thus, if you will, the theory of multiplicities, it seems to me, is radically opposed, in this sense, to structuralism. And Foucault is right, he’s entirely right to say, already in Archaeology of Knowledge, that he is not structuralist.

I believe that, actually, he is among those who believe in a doctrine of multiplicities—whereas multiplicities have nothing to do with structures. They’re something else. Why? Because, once again, they are rules for passing [règles de passage] between heterogeneous systems, and not at all formation rules for homogeneous systems. So, you’ll say: in order for there to be transitions between heterogeneous systems, there must surely be systems each of which is homogeneous? No, that’s not true. If there are only transitions between heterogeneous systems, this means that for its part the idea of a homogeneous system is an abstraction, and not only an abstraction, but an illegitimate abstraction. Only the transition matters. There you have it; hence the second level.

Okay, the second level: This time, I’m considering the sentence. Well, the sentence refers to a subject, but the subject to which it refers is the subject of enunciation [le sujet d’énonciation], bizarrely, incidentally, called “of enunciation.” A sentence has a subject of enunciation, which is not to be confused with the subject of the statement. If I say, “the sky is blue,” the subject of the statement is “the sky” and it’s not the subject of enunciation.

What is the subject of enunciation of the sentence? It’s the sentence insofar as it refers to a grammatical person. What is a grammatical person? The grammatical person is “I.” “I” is the subject of enunciation of the sentence. Any “I” whatsoever? No. There are “I”s that are grammatical persons in appearance only. If I say, “I am walking,” there is no difference in nature between the sentence “I am walking” and the sentence “He is walking.” In one case, “he” is the subject of the statement, in the other case, “I” is the subject of the statement. Thus, in the sentence “I am walking,” “I” is not the subject of enunciation, it is only the subject of the statement, and interchangeable with “he.” [Pause] On the other hand: I say, “I swear it,” “I swear it”—this time the “I” is not of the same kind as the “I am walking.” Why? Because I don’t walk by saying “I am walking.” I can walk and say, “I am walking,” but they’re not the same thing. Whereas, when I say, “I swear it,” I swear by saying “I swear it.” That’s the subject of enunciation, the true linguistic person. This is the true linguistic person, this is the first person.

What is this “I,” this true linguistic person? It’s what is called, what linguists call, a referential “am,” or if you prefer, a shifter. As they say, it initiates discourse. What is its very strange property? It’s that the “I,” the subject of enunciation, designates neither a person, nor a concept. Rather, neither some thing, nor a concept. Neither someone, nor a concept. What does it designate? It designates solely the one who says it. The one who says “I” is “I.” “I” is the one who says it—that’s the formula of the referential “am.” It initiates discourse. Very well. In other words, the first person is the subject of enunciation by means of which, or to which, the sentence refers. This subject of enunciation is the “I” as first person who is irreducible to the third person. Irreducible to the third person. The “I” of “I am walking” is, on the contrary, perfectly reducible to the third person. What I have just summarized, in a very, very abbreviated way, is a famous theory, in France, at any rate, which you find all over. But I have summarized it particularly from the point of view of [Émile] Benveniste in Problems of General Linguistics,[8] since some of you who have studied some linguistics have recognized in what I’ve been saying a theme that is very close to what the English and Americans have called “speech acts” . . . [Interruption of the recording] [1:52:33]

Part 4

… Objection: Aren’t there languages with no first person? Benveniste devotes—who is an excellent linguist, so, here, I won’t . . .—Benveniste says that, even when the first person does not appear, its place is there. He refers to Japanese — uh, will you confirm this? Very good. [Deleuze is probably speaking to Hidenobu Suzuki who is recording the session] — It goes without saying, on this point, that in a sentence, this “I” as the subject of enunciation can of course be implied. There’s no need to quote me sentences that are not of the “I swear it” type. There are obviously plenty of those. And if it’s implied, that makes no difference: the sentence refers to a subject of enunciation that is implied or explicit. Good.

In other words, I would say: this subject of enunciation is an intrinsic constancy, it’s an intrinsic constant. And here, you’ll note that anyone at all can take the place of this linguistic “I.” “I” is the one who says it. Indeed, I’ll say “I,” but you’ll say “I” later on, or you’ll say “I” at the same time. “I” is the one who says it. Hence, the formula for the sentence, here, is: intrinsic constant, extrinsic variable. The intrinsic constant is the subject of enunciation, the referential “am,” the shifter. The extrinsic variables are the infinity of individuals who can say “I.” Alright? I would thus define the sentence by its intrinsic constant, the variables being necessarily extrinsic. This is the form of the “I” in linguistics. [Pause]

Very well. And so, perhaps all this is valid for sentences, but that shows that sentences, well, they’re not anything very interesting. Because—and here I’m hooking back up with Foucault—because, because what? Because at the level of statements, you’re going to see that it’s something else entirely. A statement indeed refers to a subject, right, no problem there. It refers to a subject. Ah, but things get complicated because not only does it refer to a subject, but it runs the risk of referring to lots of subjects; it rather has too many of them. You can sense already that the “I” will not be suited to expressing the subject of the statement. It has too many subjects. Because, on the one hand, you see, the subject is highly likely to vary in nature from one statement to another.

The second point: for one same statement, it is highly likely that it has numerous subjects, which of course are not reducible to a “we”—numerous heterogeneous subjects … yes, so let’s start. Numerous . . . The subject is very different, depending on the statements. Well, yeah. [Pause] So, here is a curious text, taken from a lecture, “What is an Author?” [1969] Foucault says: does a statement necessarily have an author? He says: no, a statement may have an author. There are certain statements that have an author, notably, literary statements, for example. Someone tells me something, and I say, “who’s that from?” And they answer: “that’s from Victor Hugo.” There is an author. So, certain statements have an author as their subject of enunciation.

But there are statements that have no author. For example, a letter I write. Am I going to say, I am the author of the letter? Sometimes, yes. I’ll say “I am the author of the letter” if it’s an anonymous, criminal letter. In that case, “author” no longer means “literary author,” it means “author of the crime.” An anonymous letter has an author: auctor delictis! See that? I just did what Krafft-Ebing does, I just produced a statement. As Foucault says, it’s not hard to produce statements [Deleuze laughs], we produce them all the time and yet they are rare, he says, in fact, because . . . the two things are very consistent . . . well, no matter.

So, apart from that, a letter has no author! Ah, right, it has no author, it has a signatory. Is the ‘author’ function the same thing as the ‘signatory’ function? No. If I write to a friend: “I can’t make it to the meeting, cheers,” uh, I can’t say that I am the author of the letter, I am the signatory to the letter. But what if I am Madame de Sévigné . . . ? Ah, here things become more complicated. I am a signatory in relation to my daughter to whom I am writing, my cherished daughter, but I am also an author, since my daughter has my letter sent round in literary circles, saying “Have you seen the letter my mother just sent me? You won’t believe how good it is!” And since public readings of Madame de Sévigné’s letter take place, she is an author. This is how one same statement has two subjects: Madame de Sévigné as an author, Madame de Sévigné as a signatory—those aren’t the same. Good.

Let’s take a case like [Marcel] Proust, who is cited by Foucault. The first sentence of Remembrance of Things Past: “For a long time I used to go to bed early.”[9] Foucault asks a very simple question—but I think we are now prepared to understand it: Is it a sentence? It stays the same. Is it the same statement? If I am the one who says it, I could have happened to say it by chance one day, I said to a friend, just off the cuff, “oh, you know, for a long time I used to go to bed early,” without knowing that it was in Proust. It’s not a very, very complex sentence . . . I’m not an author, I am, at that moment, the speaker of the sentence. But when Proust writes it as the first sentence of Remembrance of Things Past, he is the author of the sentence. Does the sentence refer only to an author? No, it refers to a narrator, who is not the author. The sentence has two subject positions: the author, the narrator.

A letter has a signatory and not necessarily an author. And Foucault continues: a contract has a guarantor—that’s actually the technical term—it doesn’t have an author. A text that you read on a wall in the street has a scriptor, which is not the same thing as an author. You see, there’s a huge, there’s a huge . . .: author, narrator, scriptor, signatory . . . at any rate, the list is wide open, you can make some up, you can make up plenty of them. And I stress that in my examples—I’ve already gone over to the other case, namely: one same statement that refers to a number of types of subjects. Madame de Sévigné’s statement, Proust’s statement, which goes by way of an author and a narrator. Or else—for those who were here in other years, we treated this at some length—the example of free indirect discourse. In free indirect discourse, you have a short-circuit of two subjects that occupy completely different positions. I’ll repeat very quickly for those who were not here, so they can understand, since, here, this is brilliant.