November 26, 1985

Fine, if we have sufficiently developed these three confrontations, we are ready to ask ourselves: as far as the “rapport” (in quotes), as far as the rapport between the visible and the sayable, what is Foucault’s own answer? Is his the same as Kant’s? Is his the same as Blanchot’s? Is his the same as the one we find in cinema? Or is there, in fact, an answer from Foucault? All this leads us to the fourth and final confrontation, to wit: why did Foucault derive so much pleasure from and such a great attraction to the poet, Raymond Roussel?

Seminar Introduction

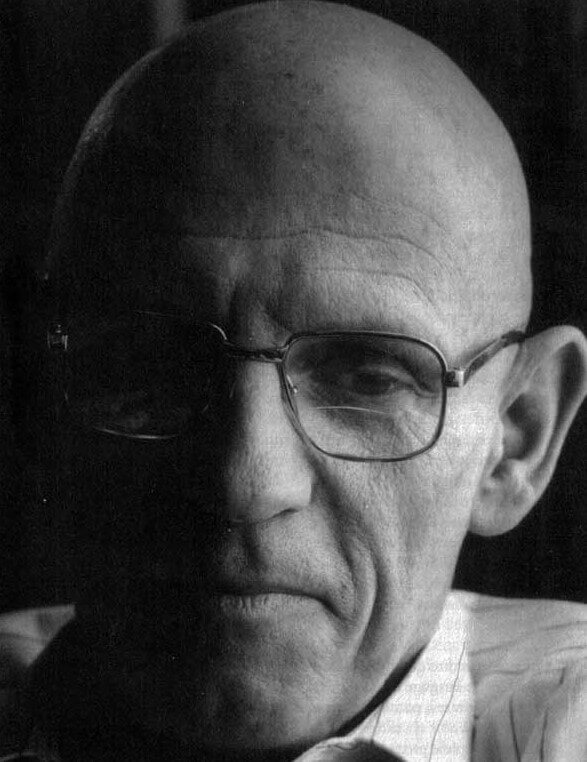

After Michel Foucault’s death from AIDS on June 25, 1984, Deleuze decided to devote an entire year of his seminar to a study of Foucault’s writings. Deleuze analyses in detail what he took to be the three “axes” of Foucault’s thought: knowledge, power, and subjectivation. Parts of the seminar contributed to the publication of Deleuze’s book Foucault (Paris: Minuit, 1986), which subsequently appeared in an English translation by Seán Hand (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

Deleuze opens where he just ended: if knowledge interlinks the visible and the statable, this occurs as both heterogeneous and with the “non-relation”, suggesting that a gap exists between the visible and the statable, which Foucault demonstrates humorously (cf. This Is Not a Pipe), logically (cf. Birth of the Clinic), and historically (cf. The History of Madness and Discipline and Punish). Deleuze identifies four confrontations as a function of this fundamental heterogeneity of the visible and the statable: 1) with Kant, and his concepts of receptivity and spontaneity; 2) with Blanchot’s statement “speaking is not seeing”; 3) with cinema’s fundamental gap between audio and the visual; 4) with Raymond Roussel’s works. Deleuze first returns to Kant’s introduction of finitude as original and not derived from an original infinite, then indicating Foucault extension of this (cf. The Order of Things). Then detailing Foucault’s three rapprochements with Blanchot (Blanchot’s notion of the Outside; the impersonal “one speaks” and even “one dies”; third, from The Infinite Conversation, “speaking is not seeing”), Deleuze examines the latter, distinguishing two exercises of speech, one “empirical” (about what can be seen), another “higher” (about the unseen, that can only be spoken), i.e. silence. While for Blanchot, seeing either slips into the purely underdetermined or is preparatory for exercising speech, Foucault gives form to the visible, crossing the gap between the two forms, particularly through cinema. Referring to work undertaken in the Cinema seminars (cf. the new use of speech Syberberg, the Straubs, Duras, Mankeiwicz, and Ozu), Deleuze reviews their different ways of establishing a relationship between speaking and seeing, particularly through empty space. Finally, the Foucault-Roussel confrontation awaits the next sessio

Download

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Foucault, 1985-1986

Part I: Knowledge (Historical Formations)

Lecture 06, 26 November 1985

Transcribed by Annabelle Dufourcq; time stamp and supplementary revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Translated by Samantha Bankston; additional revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Part 1

… You can see the problem we ran into. If it is true that knowing entangles two forms, entangles the visible and the statable, then how is that possible? How is this possible once it is said that both forms are heterogeneous and non-communicating? “Heterogeneous and non-communicating”, what does that mean? It means that, between them, there is a kind of rift, a gap, or, according to [Maurice] Blanchot’s words, a non-relation. So how can we entangle two separate forms distributed by a non-relation? It is also necessary to be sure that such a gap exists between the visible and the statable.

Now I believe that there is such a gap, and in his own fashion, Foucault shows it in three different ways, if I consider all of his books. He shows it humorously, logically, and historically. [Pause] Humorously. Well, just ask the question: if there was a form common to the visible and the statable, what could it be? And the answer is given in the little book, This Is Not a Pipe, namely: if there were a form common to the statable and the visible, this form would appear in what is called a calligram. A calligram, what is it? It is when the writing takes the very form of the visible, that is, when the visible and the readable are united.

For example, you write a poem called the egg cup, you see, the egg cup, and you give it the visual shape of an egg cup. And you start with a long enough verse… – [Deleuze moves towards the blackboard] a piece of chalk, yes… well I don’t need it, you know, but if you have one… [Pause; he draws on the board and only comments audibly in fragments] Thank you very much — Here is an egg cup… Here is my beautiful egg cup… So, you write a verse here, one that is this long, a verse this long, there would be a very short verse with just a very small word, another small word and then [inaudible]. That’s a calligram. Yeah? Good!

To say: the common form of the visible and the readable, or the visible and the statable, is a calligram, uh… it’s not making you laugh, but we can say that it’s a humorous answer. Why? Because it is a perfectly artificial form. It is a perfectly artificial form, it is not the spontaneous form of language; language is not designed to take on the form of the visible. In other words, the form of the visible is a specific form. But, if the calligram appears to be a perfectly artificial process, it will have a much more important consequence, what consequence? By what right, under the painting that represents a pipe, can I write “this is a pipe”? By what right? By what right under or next to the drawing of a pipe, or even a visible pipe, can I write “this is a pipe”? Well, it all depends on what “this” means. [Pause]

First interpretation: “this” would be the drawing of the pipe. If “this” is the drawing of the pipe, what is the statement? This is a pipe [he’s drawing on the blackboard]. However, this, the drawing of the pipe, is not a statement. So, the statement “this is a pipe” immediately turns into “this is not a pipe”.

Second interpretation: “this” is not the drawing of the pipe, “this” is the statement. If “this” is the statement, the statement “this” which is a statement, is not a pipe, a visible pipe. So, you cannot say “this is a pipe” when confronted with the visible pipe, without the statement “this is a pipe” being transformed into “this is not a pipe”. So, what corresponds to the drawing of the pipe is the statement “this is not a pipe” and not the statement “this is a pipe”. That’s funny. Hence [René] Magritte’s logical right to draw the famous pipe and write under it “this is not a pipe”. OK? All right. Are you all right? Is that clear? It’s… It’s part of Foucault’s affinity with surrealism. He’s always had that. His relationship with [Raymond] Roussel, his relationship with Magritte. It’s very surreal, this whole theme of the statement of the visible.

We will find the same thing in the more serious context of The Birth of the Clinic. In The Birth of the Clinic, Foucault shows very well that the clinic, when it was formed in the 18th century, was formed on a kind of surprising postulate: the conformity of symptoms and signs, or the conformity of visible disease and the statable disease. As if there was a visible grammar of the disease and a grammatical visibility of the disease. A disease must be simultaneously read and seen, and this is the basic postulate of the clinic. And it endures what it can endure, because in the 19th century, pathological anatomy will restore the heterogeneity of the visible disease and the communicable or statable disease, under conditions that we will see later, which is to say that it’s not about that… this is not what I want to develop today.

What I want to point out, speaking precisely of this postulate of the clinic in the 18th century, is that Foucault tells us: but it is only a dream. The dream is precisely what pathological anatomy falls into. Pathological anatomy is like the awakening of this dream. And on page 117, you’ll find this passage that interests me a lot, “The clinic is a precarious balance, because it is based on a formidable postulate”, “a formidable postulate”,”…that is, that all the visible is statable and it is completely visible because it is completely statable. A postulate of such scope could only enable a coherent science if it was developed into a logic that was the rigorous continuation of it. However, the logical framework of clinical thought is not absolutely coherent with this postulate and reversibility without any vestige of the visible in the statable confines the clinic to a requirement and a limit as opposed to an original principle. The total describability is a present and distant horizon, it is the dream of a thought, much more than a basic conceptual structure. It cannot be said any better at the level of a medical example than: conformity, the unity or community of form between the visible and the statable, is not even a structure, it is a dream. It is a dream, just as the calligram is a dream. Just as the possibility of stating “this is a pipe” next to a visible pipe is a dream. So much for the humorous presentation of the irreducibility of the two forms, the visible and the statable.

I would add: there is also a logical presentation in Foucault. We have seen the logical presentation. We saw it because we spent hours and hours on “what is a statement?” And, if I summarize, the essential point here is that the statement has a specific purpose, that is, the statement has an object that is one of its internal variables. Thus, from the point of view of the logic of the statement, the statement refers to this object as one of its internal variables, it does not refer to a visible object presented as a state of things to which the statement would refer. It is the destruction of the logical theory of reference that will establish this gap between the statement that has its own internal object and the visible that is irreducible to the statement. This is another way of saying—and this time logically and no longer humorously—that the only statement that corresponds to the visible pipe is “this is not a pipe.”

Third point: historically. And this is undoubtedly what Foucault values most, because, at the very least, he updates the two previous points of view, but we would be able to find the previous points anyway. I think that what is really original in Foucault is the historical demonstration of the heterogeneity of the two forms: the visible and the statable. And, we saw that he was pursuing it in two books that echoed one other: The History of Madness and Discipline and Punish. And if I group together things that should be easy for you right now, very well, it’s good that it’s easy. What did The History of Madness tell us? Do you remember? There’s a place…. I erased the egg cup? [Pause]

The History of Madness told us: [Deleuze returns to the board] there is a place where we find the visibility of madness, [Deleuze draws on the board] which is the general hospital. I’m looking for statements that correspond. I use “correspond” in a very vague sense, in the sense of “equals X” because we already know that it is not a question of saying “it is the same form.” I’m looking for corresponding statements, and what do I find? I find statements that are medical, and not only medical, but also regulatory or literary statements, which are statements about insanity. Good. Note, you already have Foucault’s entire method, you can see how it’s not at all… how it breaks with linguistics. Madness is by no means the object, the referent of the statement, why? Because the statement has its own object, unreason. You will tell me: but unreason and madness are the same thing… No, they are not the same thing. Historically, they’re not the same thing, there’s nothing we can do about it. The madman is defined in the general hospital; the unreasonable, the man of unreason, is defined elsewhere at the level of medical statements. You will say to me: but they correspond to another. No, that doesn’t happen, because at the general hospital they do police work, they don’t engage in treatment. Of course, all this must be qualified, there is minimal care, but the fundamental act of the general hospital has nothing to do with medical operations, it has everything to do with police operations as evidenced by the grouping of madmen with, as we have seen, the unemployed, vagrants, beggars, etc.

Blanchot, who understands this very well since it is a subject common to him and Foucault, has a very beautiful analysis of The History of Madness in The Infinite Conversation. And he says: it is the confrontation… what Foucault is talking about is the confrontation of madness and unreason. Namely: how can we explain that in the 17th century a man could be enunciated as a man of unreason and find himself in the general hospital as a madman? It’s not the same form. In The Infinite Conversation, this confrontation, or, to use Michel Foucault’s expression, what would lead those who once passed the text of unreason to be condemned to madness? What is the relationship between the obscure knowledge of unreason and the lucid knowledge that science calls “madness”? Confronting madness and unreason.

The statements, once again, are statements of unreason, whereas visibility is a visibility of madness. At the general hospital, medical statements are not treated, they are statements about or unreasonable, but they are not treated at the general hospital, which makes madness visible or which is the very visibility of madness.

Discipline and Punish, in my opinion, takes the analysis further and this time considers what? It’s completely parallel to what we’ve seen, it’s completely parallel to the History of Madness. He considers the prison as a place of visibility, a place of visibility of the crime, a place of visibility of the offense and we have seen that the prison was a place of visibility, by definition, since the prison is, in fact, the panoptic. And, on the other hand, criminal law is a system of statements, and we take up the same question: is there a common form to the two? And Foucault’s answer, through long historical analyses, is: no! No. There is no common form, at the very moment when the prison appears or, if you prefer, becomes generalized, criminal law and criminal law statements search in a completely different direction. Criminal law does not include prison as its horizon. The entire evolution of criminal law in the 18th century was carried out without reference to prison. Indeed, prison is one punishment among others, so what happens? What is the criminal law concerned with? Just as medical statements were not concerned with the madman but with unreason, what are criminal law and legal statements concerned with? The offender. Delinquency is the specific object of the statements.

Why? What does that mean exactly? Delinquency is the specific object of the statements, which means that: in the evolution of the law, the statements of criminal law in the 18th century classify and define offenses in a new way. Delinquency is the new object of statements of the law, that is, it is a new way of classifying offences. We will pick this theme up again later, but for the moment I am only trying to identify a schema, an almost formal schema.

So, you have, on the visible side, you have prison, the prisoner, on the other side you have statements, delinquency, okay. You will find this entire theme: Discipline and Punish, Part Two, chapters one and two. Chapter One: Analysis of criminal law statements in the 18th century. Chapter Two: Prison does not refer to a legal model. Prison is not caught at the horizon of the objects of the criminal law statement. Then where did it come from? It comes from a whole other horizon, which is what? Disciplinary techniques. Disciplinary techniques that are absolutely different from legal statements. Disciplinary techniques that you will find in the school – you can see how far this is from the law – in the school, in the army, in the workshop…. It is a completely different legal horizon, and we can have a military horizon, a scholarly horizon about which the same thing should ultimately be said: never can a legal statement say, in front of a prison, “this is a prison”, the legal statement should say, in front of a prison, “this is not a prison”. Perfect.

Second point. Of course, you have to expect an objection, of course the prison produces statements. And, of course, criminal law, as a form of expression, refers to particular contents. Criminal law refers to content, i.e., to the extent that criminal law statements classify offenses in a new way in the 18th century. In the visible world, it is necessary that, apart from the statements, offences themselves have changed in nature. And, as we have seen, in the 18th century, there was a tendency to create a kind of mutation, and if not a mutation, at least an evolution of offenses, with offenses being attributed more and more to property offenses. And Foucault devotes three, four pages to this very, very important, very interesting change, which coincides with the end of the great jacqueries, the end of the jacqueries in 17th century crime was essentially an attack on people, with the great gangs, the rural jacqueries, and in the 18th century there is a kind of conversion, a change in offenses that has been very well studied by a historian named [Pierre] Chaunu. In the archives—these are things that can be found in the archives—he worked a lot in the Norman archives to try to show how offenses based on small criminal groups, unlike previous large gangs, develop statistically into types of fraud, damage to property, and no longer harm to individuals.

Well, then, I must say that the statements of course refer to extrinsic content and that the visibilities refer to statements. For example, prison generates statements. Prison regulations. Prison rules are statements. It doesn’t really matter if the visibilities refer to statements, to secondary statements. The fact that the statements refer to extrinsic content does not prevent the statement in its form from never having the form of the visible and the visible in its form from never having the form of the statement.

And yet – a third element – and yet, it’s as if there is a crossroads. And yet, there is a crossroads. That is, when the prison system imposes itself, coming from a completely different perspective than the legal one, then the prison is responsible for achieving the objectives of criminal law. It comes from somewhere else, it has a different origin than criminal law does, but once it knows how to impose itself… [Interruption of the recording] [29:31]

Part 2

… But I believe that, nevertheless, I am right in my presentation of Foucault’s thought. I am right because, if you look at the texts more closely, Foucault distinguishes two types of delinquency. A type of delinquency that can only be explained later, why he calls it that, and what he calls “delinquency-illegality”. I’m just saying, delinquency-illegality is a concept of delinquency that makes it possible to classify offenses in a new way. And it distinguishes delinquency-illegality from delinquency-object, with a small hyphen. When he says that prison produces delinquency, the context is very clear: it is always the delinquency-object, in my opinion. And it is true that prison produces the delinquency-object. And, the delinquency-object is second only to delinquency-illegality, i.e., the delinquency-classification of offenses.

So, this is a second stage – and I’m drawing your attention to this because, later, we will find this when we get to “what does the death of man mean?” In The Order of Things, we will see that Foucault’s historical analyses are most often binary, in the sense that they make distinctions two times, two successive times. We will have to wonder why there is this very, very curious, very striking binarity. Now let’s take a look at Discipline and Punish. The first time, prison and criminal law have two different irreducible forms, but the second time they intersect. They intersect, namely: the criminal law redirects prisoners, i.e., perpetually resupplies prisoners; the prison perpetually reproduces delinquency.

Fine, as a result, we are always stumbling into the need to maintain these three points of view that we are trying to disambiguate. Namely, the heterogeneity of the two forms, the negation of any isomorphism, there is no isomorphism between the visible and the statable. That is the first point. The second point: the statement is what has the primacy, it is the one that is determinate. The third aspect: there is mutual capture between the visible and the statable, from the visible to the statable and from the statable to the visible.

As we have seen, it is typically the case that the prison reproduces delinquency, criminal law leads back to the prison, or provides prisoners again; there you have mutual capture. You can see that all of Foucault’s thought, indeed, becomes irreducible and all the more irreducible to the analysis of propositions, to linguistic analysis, that you see that the visible and the statable form a completely different relationship than the proposition and the referent, than the proposition and the state of things, on the one hand. And, on the other hand: the visible and the statable form a completely different relationship, obviously, than the signified and the signifier. I cannot say: the prison is the signified and criminal law is the signifier. Neither a referent of the proposition nor a signifier. [Pause]

Foucault can therefore, quite rightly, consider that his logic of statements coupled with a physics of visibility is presented in one form…, or rather in two new forms. As a result, I took all this up again, well, I don’t know, I hope I didn’t talk about it in the same way… as a result, we are facing it, at this level — I’m making a connection to our previous session — we found ourselves faced with four confrontations as a function of this fundamental heterogeneity of the visible and the statable. We found ourselves faced with four confrontations.

The first confrontation was the one with Kant. And why was it necessary, it was necessary for a very simple reason: it came to mind, like that, like a kind of mist, that, after all, Kant had been the first philosopher to build man from and on two heterogeneous faculties. The faculty of receptivity – and, after all, the visible is very similar to receptivity – and the faculty of spontaneity, and after we saw that the entire statement was determinate, that it had primacy, it looks very similar to a kind of spontaneity. Hence the necessity for a confrontation with Kant under the general question: can we say that Foucault is, in a certain way, neo-Kantian?

The second necessary confrontation was the one with Blanchot, which we have had the opportunity to invoke quite often. Since one of Blanchot’s fundamental themes is: speaking is not seeing. Blanchot’s “speaking is not seeing” and Foucault’s formula “what we see is not found in what we say”, “the visible is not found in the statable” seem to immediately impose this second confrontation: what is the relationship between Foucault and Blanchot?

The third necessary confrontation was the one with cinema. Why? Because a whole aspect of modern cinema and undoubtedly the greatest contemporary directors are defined in the most basic way, if we look for the most basic character in these directors, we can say: they have introduced a fault, a fundamental gap between audio and visual in cinema. And this is no doubt how they have promoted the audiovisual to a new stage by introducing a gap between seeing and speaking, between the visible and the spoken word.[1] And each of you is able to recognize three of the greatest names in cinema, in contemporary cinema, namely: [Hans-Jürgen] Syberberg, the Straubs [Jean-Marie Straub and Danielle Huillet] and Marguerite Duras.

However, I would just like to point out, because this is important to note if we have time, that Foucault obviously had a very, very profound interest in cinema, particularly in the cinema of Syberberg and in that of Marguerite Duras. I don’t know how he felt about the Straubs, but I assume he was very interested in the Straubs. In fact, Foucault was almost directly involved in a film that I saw, but that unfortunately I can’t remember, which was a film that René Allio made about Foucault’s research on Pierre Rivière…[2] Pierre Rivière, who had a case of criminal monomania, and who sold off all he had, a little peasant who liquidated everything he owned, Allio made a film about him, so I would really need someone to help me when we get to that point, if anyone here remembers the film for a very simple reason, because Foucault published a notebook about the little guy, Pierre Rivière, where Pierre Rivière explains in a school notebook… it’s part of… it was the first of the lives of infamous men that Foucault dreamed about. Pierre Rivière was an infamous man, a little infamous man such as Foucault wanted… dreamed about.

So, there is a natural problem here: what is the relationship between seeing and speaking? There is Pierre Rivière’s notebook and then there is his visible behavior before the crime and the visible crime. What was the relationship between Allio’s film and…? Is it just a voice-over reading the notebook? It’s a problem. And if it’s not a voice-over reading the notebook, I make a hypothesis, it’s because if it’s a voice-over reading the notebook — I can’t remember, I can’t remember at all — if it’s a voice-over reading the notebook, it’s because the filmmaking didn’t live up to what Foucault wanted. But then what else can we do? We will see, how contemporary cinema works, of which we can say that cinema that has completely broken off from voice-over by force, it is forced… it had to break off… well, that’s the third point.

A student: [Inaudible]

Deleuze: Is it hot? Is anyone still smoking? Oh no, now, be nice, you’re going to have a break, right? And you can smoke during the break. There you go. But who is smoking? Oh, yeah? Already when we… Yes, open that up a little bit, right? You’re out of control? Out of control. [Pause] Did you see that, who is smoking? Denounce them! [Laughter] Listen… huh! Pretend that you are in the subway… Yes, but some people smoke in the subway… Is that better?

A student: Yeah, yeah.

Deleuze: Good… We’re at the last confrontation. Well, if we have conducted these three confrontations well, we are ready to ask ourselves: but, as for the “relationship”, between quotation marks, as for the relationship between the visible and the statable, what is Foucault’s own answer? Is it the same as Kant’s? Is it the same as Blanchot’s? Is it the same as the one from cinema? Or does Foucault have a unique response? This leads us to the fourth and final confrontation, namely: why did Foucault feel so much pleasure and affinity with the poet Raymond Roussel? What did he get out of Raymond Roussel? Why did he feel the need to write a book on Raymond Roussel?

That’s it, that’s our program. And we already started it, since the last time we said: well yes, there is a very curious Kantian adventure, so it was the first confrontation. There is a very curious Kantian adventure that is what? It is because Kant is the first, I said, to construct man according to two heterogeneous, irreducible faculties. And what are these two irreducible heterogeneous faculties? They are, you remember, they’re receptivity and spontaneity, but what are they? Well, receptivity is the faculty of intuition, and by intuition, in the Kantian sense, we must understand something very precise; it is the form in which all that is given to me is given. What is the form in which all that is given is given? The very rigorous Kantian answer is that everything that is given is given in space and time. So, space-time is the form of intuition. All that is given is given in space and time, space and time are the form of intuition in which I grasp everything that is given to me and everything that is givable, everything that is givable. If someone spoke to me about something that is not in space and time, I would say, it cannot be given to me. Maybe I can think it – that’s something different altogether — it can’t be given to me. This is the faculty of intuition, or space-time as the first form.

And second form: spontaneity, this time it is “I think”. Why is “I think” spontaneity? Or a different activity from receptivity? Well, because “I think” is the statement of a determination. It’s a determination. So, I talked last time about this consideration: but why does Kant construct man in this way and why wasn’t it done previously? Why did this idea of heterogeneous faculties…Why did we have to wait for Kant to do it? My answer was very simple: metaphysics cannot — it is not that it does not want to: it cannot — metaphysics cannot attain this theme of heterogeneous faculties. And to achieve this, Kant instantiates what he calls his own revolution, namely the substitution of criticism for metaphysics. Why, can’t metaphysics do this – as we saw last time – it is because what defines metaphysics from Christianity and its relationship with theology is the position of the infinite as primary in relation to the finite.

It’s only when infinity is primary in relation to the finite that our faculties are necessarily homogeneous by law. How odd, though. Why? Why, if infinity is primary in relation to the finite, are our faculties homogeneous by law? Because we are actually finite, but finitude is only a fact. What is primary in relation to the finite is infinity and infinity is what? It is first and foremost God’s understanding. Infinite understanding…all of the metaphysics from the seventeenth century is full of considerations about infinite understanding. But what is infinite understanding? God’s understanding? God is the being for whom there is no given, indeed God creates and creates ex nihilo, from nothing, there is not even any material given to him. Therefore, the distinction between a given and an action does not exist for God.

In other words, the difference between the given and created does not exist for God. The difference between receptivity and spontaneity does not exist for God. God is only spontaneity. And what is it when the given is given? The given is a fallen spontaneity. There is only the given for the living beings, because living beings are finite. The given is only fallen spontaneity. In other words, we, being finite beings, we say “there is something given”, for God there is none. In other words, it is only our finitude that makes the difference between receptivity and spontaneity. This difference does not apply at God’s level. But God is the law. I mean: it’s the state of things as is the case in law.

That’s it, it’s very simple, you see, well, what is Kant doing? For Kantianism to be possible, there must be a promotion of finitude, finitude must no longer be considered a mere fact, made by the living being, finitude must be promoted to the state of constituent power. See how, with constituent finitude, you can say to yourself: well, that’s why [Martin] Heidegger likes to appropriate so much from Kant. Kant is the advent of a constituent finitude, that is, finitude is no longer a simple fact that is derived from an original infinite, but rather it is finitude that is original. That’s the Kantian revolution. From then on, what comes to light is the irreducible heterogeneity of the two faculties that compose it, receptivity and spontaneity, the receptivity of space-time, the spontaneity of “I think”. Finally, man becomes deformed. Deformed in the etymological sense of the word, i. e. de-form, it limps on two heterogeneous and unsymmetrical forms, receptivity of the intuition, spontaneity of “I think”. That’s where we were. So, we started again, I think, but I hope we added some things. So that you are ready to make just a little bit of an effort towards something a little more difficult.

It is because, if you have followed this theme of Kant, you can expect something from Descartes to Kant — from Descartes who still explicitly maintained the primacy of the infinite over the finite, and who was therefore a great classical thinker, that is to say from the 17th century — well, from Descartes to Kant, the famous formula of the cogito, “I think, therefore I am”, changes everything in its meaning. And we’re going to see… if I revisit this, and if I revisit it it’s because we’re going to see that it concerns Foucault directly. And, after all, the last part of The Order of Things contains numerous references to Kant and takes up the Heideggerian theme of the Kantian revolution, which consists in this: having promoted its constituent finitude and thus broken free from the old metaphysics that presented us with an infinite constituent and a constituted finitude. With Kant, finitude is what becomes constituent. Now, Foucault recalls this theme very well, I do not think that these are new points from The Order of Things, simply that Foucault uses this admirably and perhaps it is Heidegger who is the first, that… undoubtedly it is Heidegger to have defined Kant by this operation of constituent finitude. And so I am saying right now that the cogito must take on a whole new meaning.

And, indeed, in Descartes, I ask you to pay careful attention, in Descartes how is the cogito introduced? I suppose even those who don’t know anything, huh… so I’ll speak for everyone, even those who don’t know anything at all about Descartes. Descartes first tells us “I think”. What is “I think”? It’s the first proposition. Proposition A: “I think”. Good, he thinks, okay. What does that mean, “I think”? “I think” is a determination. It is a determination, and what’s more it is an indubitable determination. Indubitable! And yes, there is no doubt about it. Why is it indubitable? Because I can doubt anything I want, I can even doubt that you exist, and I can even doubt that I exist. Even me, yes. What can’t I doubt? There’s only one thing I can’t doubt, and that’s that I think. Why can’t I doubt I’m thinking? Because doubting is thinking. It’s not about talking, saying “Oh, really? Oh, really?” You have to try to understand. I can doubt everything, I can doubt that 2 and 2 are 4. What do I know about 2 and 2 being 4? I don’t know, I don’t know. I can doubt that. But I can’t doubt that I, who doubts, thinks. So, I think it’s an indubitable determination. There you go, that’s all.

Proposition B. [Pause] We can see that the cogito is not “I think, therefore I am”, it’s more complicated than that. Proposition B: I am. And why am I? Hey, hey! For a very simple reason: it is because in order to think, I have to be. If I think, I am. The statement of the cogito, at level B, is therefore: “but, if I think, I am”. Proposition A: “I think.” Proposition B: “Now, if I think, I am.” Why is it that if I think, I am? Well, “I think” is an indubitable determination. A determination must be about something, something undetermined. Any determination determines something undetermined. In other words, “I think” presupposes “to be”, presupposes a being. I don’t know what this being is, I don’t have to know. “I think” is a determination that implies an indeterminate being. I am. And “I think” will determine “I am”, since “I think” is a determination. But the determination implies an undetermined. How beautiful all this is! Ah! I would say, there’s no reason… you understand, I hope, what I mean when…, there’s no reason to object, it’s already so tiring to understand. I think, I am. Well, yes. If I think, I am; I am what? At this level: an undetermined existence.

Proposition C: but what am I? You see: proposition C is more than “I am”, it is what I am. What am I? What am I? I’m a thinking thing. I’m a thinking thing. That is, the “I think” determination determines the indeterminate existence “I am”. The “I think” determination determines the indeterminate existence “I am”. From which I must conclude: I am a thinking thing. The statement of the cogito would therefore be: A) “I think”, B) “but to think, you have to be”, C) “so I am a thing that thinks”. There you go. In other words, I would say that Descartes operates – this is very important for me, for the future – Descartes operates with two terms, “I think” and “I am”, and only one form “I think”. Indeed “I am” is an undetermined existence and therefore has no form. “I think” is a form, thought is a form, it determines undetermined existence: I am a thing that thinks. There are two terms, “I think” and “I am”, and only one form, “I think”. Hence the conclusion: I am a thinking thing. OK?

And now, listen to Kant. Kant keeps A and B, he keeps A and B, that is, he will say: okay, I think (A), and “I think” is a determination. And he will say: OK about B, determination implies an indeterminate existence, “I think” implies “I am”. In fact, the determination must be focused on something undetermined, and everything happens as if Kant was stuck at the end of B, and he said to Descartes: you can’t go any further. He can’t go any further. He says: you can’t conclude “I’m a thinking thing”, why? Why can’t Descartes conclude this…? Because, because it’s very simple, you know. It is true that “I think” is a determination, that is, it determines, it determines what? It determines an indeterminate existence, namely “I am”.

But, but, but…still it is necessary to know in what form – listen carefully, I am going to tell you a radical secret, a kind of mystery – it is still necessary to know in what form indeterminate existence is determinable. Descartes was in too much of a hurry, once again. [Laughter] He thought that determination could directly relate to the indeterminate. And like “I think”, determination meant “I am”, the undetermined existence, he concluded “I am a thing that thinks”. Nothing at all! Because when I said, “I am”, the indeterminate existence involved in the determination “I think”, I did not say under what form the indeterminate existence was determinable.

And in what form is undetermined existence determinable? Kant’s thought is still very prodigious. You have to try to live it. You can almost get ahead of Kant. Without having read it you can become Kant, because you can guess what Kant is going to say to us. Indeterminate existence is only determinable in space and time, i.e., in the form of receptivity. The indeterminate existence “I am” is only determinable in space and time. That is, I appear in space and time. That is, undetermined existence is only determinable in the form of receptivity. What a story! Why?” I think” is my spontaneity, my active determination. But now my spontaneity, “I think”, only determines my indeterminate existence in space and time, that is, in the form of my receptivity. What’s is that going to do? It’s going to be something strange!

In other words, the determination cannot directly relate to the undetermined, the “I think” determination can only relate to the determinable. [Pause] There are not two terms, determination and indeterminate, there are three terms: determination, indeterminate, determinable. Descartes skipped a term. But then, if my undetermined existence is only determinable in the form of receptivity, that is, as the existence of a receptive being, I cannot determine my existence as that of a spontaneous being. [Pause] I can only imagine my spontaneity, I can only be receptive, which is only determinable in space and time, I can only imagine my own spontaneity and represent it as what? As someone else controlling me. Like someone else controlling me.

In other words, I don’t know when, last year or the year before – I say this for those… – when I connected Kant’s cogito to [Arthur] Rimbaud’s famous formula, “I is an other”, it seems to me that I was spot on. I is an other. I was spot on if Kant was spot on.[3] Fortunately, Kant says it literally, so everything is fine. Kant literally says it in the first edition of the Critique of Pure Reason, and I will read the text slowly, because you need to understand it. “I think” expresses the act that determines my existence…” no difficulty there, it means the “I think” is a determination and, by the same token, it is my spontaneity. “I think” expresses the act that determines my existence. “Existence is therefore already given by this,” undetermined existence, that is. “Existence is therefore already given by this… but not in a way to determine it.” Understand: in my opinion, I am sure the translation is not that great here, but it is not terrible, “but not in way to determine it” means: not the way in which it is determinable. Existence is therefore already given by this, but not in the way that undetermined existence is already determinable. “This requires intuition of oneself”, that is, receptivity…”This requires the intuition of oneself, which is based on a form”, “which is based on a form”, “that is, time that belongs to receptivity.” Time is the form in which my existence is determinable. “I cannot, therefore,…”—this is the essence of Kant’s contribution—“I cannot, therefore, determine my existence as that of a spontaneous being, but I can only imagine the spontaneity of my act of thought or determination, and my existence is only ever determinable in intuition. Like that of a receptive being. My existence is only determinable in time, as the existence of a receptive being, which being receptive, therefore, represents its own spontaneity as the operation of another on it.” See how beautiful it is?

When I said: there is a gap, it’s the same thing. There’s a fault in the cogito, the cogito is completely cracked in Kant. The cogito was as full as an egg in Descartes, why? Because he was surrounded, bathed by God. With constituent finitude I walk on two unequal legs, receptivity / spontaneity, it is really the fault inside the cogito: With “I think”, spontaneity determines my existence, but my existence is only determinable as that of a receptive being, so I am receptive, I represent my spontaneity as the operation of another on me and this other is “I”. See? All right.

What is Kant doing, where Descartes saw two terms and one form, he sees three terms and two forms. Three terms: determination, indeterminate, and determinable. Two forms: the form of the determinable, and the form of determination, i.e. intuition, space-time and “I think”, receptivity and spontaneity. There are two forms. Two heterogeneous forms. Receptivity is not a degraded spontaneity, as the 17th century metaphysics believes or tries to believe, there is heterogeneity between the two, so that I, being receptive, can only prove myself in time, can only imagine my spontaneity as the operation of another on me.

Well, what does Foucault tell us about how he is neo-Kantian? Foucault is neo-Kantian, because he posits the following shift — I already mentioned this, but I don’t want to… — space-time becomes light. It seems, to speak really quickly, that we can say that Einstein passed through this. All right. Kant’s space-time becomes light and defines the form of receptivity. The visible, the visible in the sense that we have seen it, since this visible will not even be given any meaning. This is the condition under which all sensory data is given. As we have seen, light is not attached to and is not dependent on sight, it is the condition under which all sensory data is given, it is the form of receptivity.

And what is the form of spontaneity? It is no longer the “I think”, it is the “one speaks”, the being of language or the “there is” of language. [Pause] This is the form of determination. There are two irreducible forms. There are two irreducible forms and, in this respect, at the end of the transformations that he subordinated to Kantianism, Foucault is necessarily faced with the same problem as Kant. What does the same problem as Kant mean? It means… well……. between receptivity and spontaneity, between light and language, between the determinable and the determined, there is a gap or non-relation, and yet there must be a relation… [Interruption of the recording] [1:16:00]

Part 3

… the last time, Kant’s answer, and, even if we summarize it, it will help us with our future analyses of Foucault, Kant’s answer will be: yes, we need a third element, we need a third, and not only do we need a third to connect the unrelated, i.e. space-time and “I think”, receptivity and spontaneity, but this third must be formless. An informal element, an obscure informal element which, on the one hand, is a great mystery, that would be homogeneous to intuition, space and time, and, on the other hand, would be homogeneous to “I think”, to the concept.

So: receptivity and spontaneity would be heterogeneous, but there would be a third instance that would be homogeneous, for its own sake, to intuition and homogeneous to “I think”. And that’s weird, what a strange feature! Kant tells us: it is what is most mysterious about man, and it is imagination. What is most mysterious about man: a feature that is homogeneous to each of the two heterogeneous features. And why is he saying that? Is it arbitrary? It’s not… he means something very simple… Look again, he says: the essence of the imagination is to schematize and what is a schema? Well, there you go. A scheme is a funny thing. A schema is a set of spatiotemporal determinations that correspond to a concept. A set of spatiotemporal determinations that correspond to a concept. Example: an equilateral triangle, it has a concept, it is a triangle [Pause] that has three sides and three equal angles. All right. A rectangular triangle has a concept, it’s a triangle that has a right angle.

What is the schema? The schema is the construction rule. How do you build a rectangular triangle, right? [Pause] I see well, there are some who have a blatant smile, I say to myself: they are ones who know and there are some who take on an abstract, annoyed expression, and I say to myself: these are the ones who have forgotten. So, I’m not going to take away the surprise, you can refer to your ordinary geometry textbooks, but for example, to make a rectangular triangle, you have to draw a circle. How do we draw, what is the rule for making a circle? Huh? I’m sending you back to your regular textbooks. This will be the schema of the circle, the rule for making a circle. Well, if you draw a circle, you take the semicircle. The construction of the semicircle, how do you get a semicircle? All of that: schemas referring to schemas, huh. And then you draw your rectangular triangle, the construction rule is its schema. Similarly, an equilateral triangle, how do you make it? What do you need to make it? A ruler and a compass. Rulers and compasses are construction instruments. Huh, you see, you draw a line with the ruler, you take one end of the line, you use your compass, you do something, you see… well… there you go. Good. So these are construction rules, but admire what a construction rule is. A construction rule is a rule that constructs the object of a concept, the object that constructs that produces the object of a concept, does so where? In space and time.

Well, that’s enough. That’s great. That’s great. Here again, it is a very great Kantian discovery: the schema, the schema of the imagination. It’s a great concept. So, the schema is, on the one hand, homogeneous to space and time since it determines space and time, it is a determination of space and time. You can tell me: what role does time play in this? Well, just take a schema like that of the number, the schema of the number is what? The schema of the number is the rule according to which I can always add a unit to the previous number, that’s the schema of the number. It’s a temporal schema. So a scheme is homogeneous to space and time, since it determines a space-time. But it determines space and time as the corresponding….. as conforming to a concept, equilateral triangle, number… You see, it is therefore homogeneous to the space and time it determines and homogeneous to the concept whose construction of the object it allows.

Here’s a practical exercise: the definition of the lion is the concept. Oh? You define the lion. [Pause]…. We can conceive of several definitions. And what is the lion’s schema? You see that a schema is not an image at all. If I say: an image of numbers, you will say “two” or “three hundred”. And that’s not the schema of number, it is the rule of production of any number. If I tell you: the image of an equilateral triangle, you’ll have no trouble, you’ll just, you’ll draw an equilateral triangle. Finally: you’ll have no difficulty, I don’t know… but…. you’ll make one, regardless of whatever sheet of paper you use, you’ll make one more or less. All right. But that’s not the schema, the schema is not an image, it’s the rule of production of any image as corresponding to the concept or as conforming to the concept. So, the lion’s scheme is not a lion. A lion image is a lion, this one, oh yes, the lion I saw at the circus the other day or the one I saw on TV… well, that’s not a lion schema, it’s much better than that. That, indeed, is part of the mystery of the imagination. What would a lion’s schema be, for example? It is always a dynamism. It is a spatiotemporal dynamism. There, you can dream, you can dream, let’s dream. When you have a concept, a concept like the cow or like the lion, what is the cow scheme? It’s not this cow, that’s an image, that cow you know particularly well is an image of a cow.

But the cow schema, I’ll tell you what it is… we can vary, huh, there. Uh, the cow schema, for me, is the powerful migratory movement that takes any herd of cows from a meadow at any given time. Ah, see? … Suddenly, these animals that were completely, that were grazing, there, each one, a little scattered, all of a sudden, they migrate to the prairie, what a terrible five o’clock in the evening, five o’clock in the evening, the cows migrate to the prairie, spatiotemporal dynamism. What is the lion’s schema? It’s a scratch, it’s a spatiotemporal dynamism, it’s not part of the lion’s conceptual definition. Having claws, yes, it’s part of the lion’s conceptual definition, but the dynamism of the gesture…that would be the schema. In other words, it is a spatiotemporal determination that corresponds to a concept. There is nothing more paradoxical, since space-time and the concept are strictly irreducible, how can there be schemas that cause determinations of space and time to correspond to concepts.

That’s why Kant tells us: schematism is the most mysterious art. Well, we see a third instance where the two forms are not, the two forms are not reducible to each other. The two forms are not in conformity, but there would be a third instance which would, on its own, conform to one of the two forms and to the other of the two forms. The condition is that Kant leaves us… he leaves us, he can’t go any further. [Pause] The condition, in my opinion, is that it only makes sense if the schema is informal. But then, if it is informal, how can it be consistent with both forms? Kant’s answer is difficult: an art buried in the depths of the imagination. Buried. We shouldn’t ask a philosopher, whatever his genius happens to be, to go further when we’ve already gained so much more ground than Kant has, when we’re beset by other problems, it’s not something missing… It’s up to us, if we’re Kantians, to try to go further thanks to him, that’s all. So, will this be the case with Foucault? What will Foucault’s answer be? We know that, on this matter, we can no longer be Kantian, since Kant tells us nothing more. But will there be — that’s exactly my question for later — will there be, in Foucault’s case, something that works even vaguely like Kant’s schematism of the imagination?

So, since we can’t push the confrontation with Kant any further, I’m moving on to the second confrontation: Blanchot. And, if we were to make a general comparison, at what point is there a rapprochement between Foucault and Blanchot? — What time is it? Well, I think we could group the themes… Ah….. we could group the themes of a possible Foucault-Blanchot rapprochement. I see three of them. I see three fundamental ones. One, we will see it much later, so I can only quote it, because…. The second one we have seen at least in part and, the third one, that’s the one on which we will try to insist. But so that here I group them all three, namely, a certain… I can’t even say “conception”, but a certain call to the outside. The outside. The outside as a fundamental notion for Blanchot as for Foucault.

What is the outside? Well, this covers both the criticism of every interiority, plus it strikes me…the criticism of every interiority and also: the outside is not reduced, but exceeds the outside, because the outside is still a form, the outside as an informal element. And Foucault will pay tribute to Blanchot in the Critique journal in an issue devoted to Blanchot, and Foucault will write a very beautiful article entitled “The Thought from Outside.”[4] What does that mean, thought that comes from outside as opposed to thought that comes from inside? The thought from outside, I think the theme from outside is a very original theme in Blanchot, and that Foucault takes it up in his own way. So, we’ll have to see, but that’s for the future because we’re far from there right now.

The second similarity, as we have seen, is the elevation of “on” or “he”, namely the common criticism in both of any personalism and any personology, even in linguistics. We saw the devaluation of the “I” in favor of the non-person, that is, the third person, and, beyond the third person, beyond even “he”, “one”. And, in Blanchot, not only is there a “one speaks”, perhaps, we will see, perhaps a “one sees”, but above all there is a “one dies”. It is in The Space of Literature that the “one dies” line develops most.[5] And perhaps this line of “one dies”, which is so profound in Blanchot, and not “I die”, but death as an event of “one”, perhaps it is one with the problem we are saving for the future, that is, the problem from outside. “One dies” is a death that comes from outside. Good. In Foucault’s work, as we have seen, you will find, at the very level of the theory of the statement, how the first and second person give way to a non-person, that is, the position of the subject as a variable of the statement, irreducible to everything “I” and which is always in the form of a “he”, every “he” taking place in the procession of a “one”. “One speaks.”

And the “one dies”, you will also find them, but reinterpreted by Foucault. Because I believe finally, and this is one of the very… moving things about Foucault’s death, which is that Foucault is one of the men and there are not many of them, who died more or less as he thought death would be. He didn’t stop thinking about death much, although Foucault wasn’t sad, uh…he had a rather special relationship with death, I think that was his own way of thinking about death and very strangely enough he died in the way he thought about death. And what does that mean? I think that in Birth of the Clinic, you find a rather long analysis of [Xavier] Bichat, of Doctor Bichat, a very famous 19th century doctor who is famous precisely for having founded a new relationship between life and death, a new medical relationship between life and death. However, if you read these pages of Foucault’s in Birth of the Clinic, there is something that is obvious in them. It is because it is not a simple analysis, however ingenious and brilliant it may be, there is a kind of emotional tone in Foucault’s pages on Bichat, which, it seems to me, is as if Foucault was telling us indirectly, by using a Bichat inspired analysis, something that fundamentally concerned him.

And, if you ask yourself, what was new about the way Bichat conceived death, I think there is something new, so new that Bichat is a very fundamental modern thinker. It is that there was a certain conception that drags on everywhere from death, death as an indivisible and unbreakable moment. I would say that this is the classic conception of death, death as an indivisible and unbreakable moment where life ends. And you find this conception still very current, that’s what I would say… that’s it, that’s a criterion of the classical man. At the time of death, something incredible happens. This classic conception still animates [André] Malraux’s famous phrase: “Death is what transforms life into destiny.” You find the equivalent in ancient conceptions. I’m using an example from the moral conceptions of antiquity. If, for example, when we are told: the wise knows very well that we cannot say “I am or I was happy” before death, that is, death as an unparalleled moment can change the quality of a life and can retroactively change the quality of a life. So, we have death as the ultimate moment, death as the limit. I would say: this is the classical conception you’ll find among moralists, but also among doctors, and philosophers…all of this is the classical conception. Many of us live in this classical conception. It’s interesting to wonder how everyone thinks about death.

Not at all for Foucault. Nor with Bichat. I think that Bichat has two fundamental innovations. Bichat is famous for his definition of life, which opens his great book on life and death, and is a sublime book. This definition of life is – and this is famous in the history of medicine: life is the totality of functions that resist death. This definition seems weird, why? It even looks useless, because it is completely contradictory. Once we are told that death is non-life, but in the name of classical thought… The classical man cannot understand Bichat’s definition for the simple reason that… death is non-life, defining life as “the totality of functions that resist non-life”, it does not seem…it does not seem reasonable.

So, death as an unbreakable and immeasurable moment prevents or removes any meaning from Bichat’s sentence. But in fact, it means that Bichat is not a classical man. Because on two points Bichat’s formula takes on a frightening meaning. Namely: it is the affirmation, first point, that’s the first originality with respect to classical thought: it is the affirmation that death is coextensive with life, that it is not an unbreakable moment, that it is not a limit of life, that it is coextensive with life. That’s what it means… It’s not confused with life, but it is coextensive with life. Death is a potential coextensive with life. It doesn’t take much effort to deduce the “one” from it – without mixing everything up, Bichat does not say “one dies” – but, if death is a potential coextensive with life, one dies. [Pause]

And, the second novelty of Bichat’s thought, far from being an unbreakable moment, is that death is disseminated, pluralized, multiplied in life. It is both coextensive with life and it spreads into life in the form of partial deaths. So, death as a potential coextensive with life, first point; second point: partial, fragmented and multiple deaths, which continue after the big death, since what is called the big death is a legal death. Well, we don’t stop dying. Just like we started dying. And if you look at nothing but the table of contents – for lack of anything better, it’s already there, in Bichat’s great book – you’ll see that it’s about heart death, brain death, lung death and all kinds of other deaths. And it is with Bichat that this theme of multiple and partial death or multiple and partial deaths begin.

Now if I come back to Foucault, I think that Foucault is a man who thinks of death in a non-classical way, he thinks of death or he lives death in Bichat’s way. And I think he died that way. He died like that, which means what? It means: he died in the form of a “one dies”, taking his place – to speak like him – by taking his place in a kind of procession of death, by taking his place in a “one dies”, and he died in the same way as successive partial deaths. Then there would be, if you will, a whole development specific to Foucault with the theme in common with Blanchot, but in his own way and in his own style, that is to say with this reprisal of Bichat, but ultimately a confrontation is essential.

But I’m moving on to the third point of confrontation with Blanchot, which is the one that comes quite naturally to the place we are at in our analysis. And I am obviously referring to the great text… it is everywhere in Blanchot, but Blanchot’s most decisive text in The Infinite Conversation, the piece entitled “Speaking Is not Seeing.”[6] At this point in our analysis, speaking is not seeing because of the deformity, i.e., the heterogeneity of the visible and the statable, to which Foucault’s formula responds: “What we see cannot be found in what we say.” “Speaking is not seeing.” And I say to myself: let’s try, Blanchot’s text is very beautiful, with great poetic virtues, so let’s try, we, as non-poets, as we enumerate, to specify what Blanchot means. Because it’s very, very interesting: speaking is not seeing. Well, here too, I’m trying to enumerate in order to go slowly.

a) What does “speaking is not seeing” mean? Well, that obviously means one very simple thing at first, and that is that there is no need to speak about what we see. You see, it’s a little different. In concrete terms. We have to start from a very concrete basis. There’s no point in speaking about what we see, because if I speak about what I see, it’s gossip, it’s not worth it. It’s not that it’s impossible, you see, it’s worse than that, I can always speak about what I see, but what’s the point? What’s the point of speaking about what you see, since you see it? You will say to me: Oh yes, but the other one doesn’t see it. What am I talking about? Ah, very well, I’m not asking for more than that! Because if I can speak about what I see, under the condition that I speak to someone who does not see, it is because far from talking about what I see, I talk about what the other does not see.

b) Anyway, speaking is speaking about what someone doesn’t see, it’s not speaking about what someone sees. Because if someone was speaking about what they were seeing or if I was speaking about what someone else was seeing, it would be enough to see. There is no reason to mobilize the word. And, indeed, if I speak to say uh… usually when I speak it is to say: “Did you see that?”, with the implication of “You didn’t see it.” “Oh, did you see the funny guy”… it means “you didn’t see him.” Or, uh, if I’m talking about this machine right now, why am I talking to you about it? Because you see another end than I do. I’ll say: “Oh, I have a little red and blue circle there, on that stupid thing… and is there one?” I don’t see it, so I’m speaking about what I don’t see. She’s not going to answer me by talking to me about what she sees, but to me who can’t see… Good, none of that is difficult. So, at the limit, if you’ve understood that, speaking is speaking about what someone doesn’t see relatively, but it’s a relative that you have to elevate to the absolute. Therefore, to speak absolutely is to speak of something that is neither seen nor visible. Oh, really? To speak is to speak about… In other words, to speak, as Blanchot says very well, is not a view, not even a freed view, that is, even a generalized view, free from the limitations of the view. Speaking is not a better view than sight, it is not a view freed and freed from its conditions. Language is not a corrected view. So, you see, it must be said that speaking absolutely means speaking about what is absolutely not visible. Only then, and only under this condition, is the language worth the effort.

Second proposition: therefore, when we say “speaking is not seeing”, we define a superior exercise of speech. I could define… Blanchot does it… I’ll try… it’s a free comment of Blanchot’s that I am suggesting to you… If you read the text in The Infinite Conversation, you may very well have another commentary. That’s how I understand it. I mean, we’re forced to distinguish two exercises of speech. One I will call an “empirical exercise”. I speak, I speak, it’s even most of the… during the day, I have to have an empirical exercise of speech. I’m talking about what I see while someone else doesn’t see it. And again, if I’m very smart, if not, the times when I’m stupid, well, I’m talking about what that I see to someone who sees it too. Uh… I’m on the phone, and I say oh the cowboys are coming… I’m not teaching anyone, he’s old enough to see it too. Uh…. Well. So that’s the empirical exercise, but the empirical exercise is, in fact, when I say “Oh, you saw, it’s raining,” I presuppose that he didn’t see anything. Very well. So I talk to someone and tell them something they don’t see relatively. So, at this level, the empirical exercise of speech, I’m talking about things that, in one way or another, could just as easily be seen. What I call “higher exercise” is: I am talking about what is not visible or, if you prefer, I am talking about what can only be spoken. Ah… but this is indeed a second proposition, because what is that? The superior exercise of speech is born when speech is addressed to what can only be spoken.

Is there anything that can only be spoken about? We can stop right there, say: no. All right, but if we try: for Blanchot there is something that can only be spoken, there are even many things that can only be spoken. Probably death can only be spoken for Blanchot, but why? What is it, what can only be spoken, and which would define the superior exercise of speech? Notice: it’s not going to help us, unless it helps us, it’s, as well, something that can’t be spoken, which is implied, what can only be spoken is something that can’t be spoken from the point of view of empirical use. Since what can only be spoken can only be spoken, but the empirical use of speech is to speak about what can also be seen. What can only be spoken is what is hidden from any empirical use of the word. So what can only be spoken is what cannot be spoken from the point of view of empirical use.

Are you all right? It’s very simple, isn’t it? I mean, it’s like mathematics. What cannot, therefore… What can only be spoken from the perspective of the superior exercise is what cannot be spoken. In other words, what can only be discussed from the perspective of the superior exercise? Blanchot’s answer will be: it’s silence. That’s right, what can only be spoken about is silence, it’s pure Blanchot and it’s beautiful, it’s very beautiful. All right. In other words, what can only be spoken is the proper limit of speech. The superior exercise of a faculty is defined when that faculty has as its object its own limit, which can only be spoken. And, therefore, also, what cannot be spoken. Yes? Good.

Third proposition. So, we expect Blanchot to tell us exactly the same thing about vision. For, if speaking is not seeing, insofar as speaking is speaking about the limit of speech, speaking about what can only be spoken, why is it that… At first sight, we should say: and vice versa. If speaking is not seeing, seeing is not speaking. That is to say, for vision too, there would be an empirical exercise: it would be to see what can be as good, something else, for example what can be as well imagined or recalled or spoken. At that moment it would be an empirical exercise and the superior exercise of sight would be to see what can only be seen. But to see what can only be seen is to see what cannot be seen from the point of view of the empirical exercise of vision. What cannot be seen from the point of view of the empirical exercise of vision? Pure light. [Pause] Goethe’s light. I only see light when it ricochets on something. [Pause] But the indivisible light, pure light, I do not see it and that is what can only be seen.

Oh, really? Well, there you go, all right. In other words, just as the word finds its superior object in what can only be spoken, so the view would find its superior object in what can only be seen. Well, there you go, sadness: why doesn’t Blanchot say it? Why is Blanchot… there is indeed the symptom of a difference between Foucault and Blanchot… Why is it that Blanchot does not say, to my knowledge, and will never say: “and vice versa”? Blanchot will never say “speaking is not seeing and vice versa.” In the text that I already quoted to you several times from The Order of Things, on the contrary, Foucault says “and vice versa,” “What we see is not found in what we say, and vice versa.” What we say is not found in what we see. He maintains that the two faculties of seeing and speaking in this respect as equals. “And vice versa.” Blanchot doesn’t say that. Is it because he’s not speaking about sight? Yes, he’s speaking about sight. He speaks about the view in two places, so it becomes more mysterious in appearance. He speaks of sight in the piece from The Infinite Conversation, “Speaking Is Not Seeing,” and he had spoken of it in another text, The Space of Literature, in the appendices or notes in The Space of Literature, under a title that suits us in advance: “Two Versions of the Imaginary.” Two versions of the imaginary: at this point, we can expect, if all goes well, that one will correspond to the empirical exercise of sight, the other to the superior exercise of sight.

I will take both texts. The text from The Space of Literature tells us: we must distinguish two images. One, the first image is the image that resembles the object and comes after it. To form an image, you must have perceived the object, it is the image of resemblance. It is an image, therefore, that resembles the object and comes after it. The other one, I’m simplifying… I’m simplifying, because it would take too long otherwise, but I think that this simplification is completely accurate, even though Blanchot doesn’t put it that way. The other – I’m taking up a Christian expression, one dear to Christianity – the other is the image without resemblance. This idea, which will be prodigious for a theory of the Christian imagination, namely, with sin, man has remained in the image of God, but he has lost the likeness. The image has lost its resemblance. Image without resemblance. And this image without resemblance, it may be because it is truer than the object – and here I’m going back to a text of Blanchot’s—it is truer than the object… And Blanchot, in these very surprising pages, says: it is the corpse, it is the corpse that is truer than myself, the corpse that is truer than me, [Pause] to the extent that those who mourn me say: “how it looks like him, how death has frozen him in some aspect.” Nor the corpse… it is not the corpse that resembles the living thing I was, it is the living thing I was that resembles the magnificent corpse that I am. The image without resemblance appeared, by dying I washed myself of resemblance, I am pure image, pure corpse. Fine.

That’s the way Blanchot thinks, right, it’s not… Uh…. There you go, that’s “Two Versions of the Imaginary,” I simplified a lot, see the text for yourselves. In The Infinite Conversation, you find the same theme expressed in a different mode. Two Versions of the Imaginary. What is it? Or rather, no, two versions…… No, that’s, no… I take back “imaginary”. In the text “Speaking Is Not Seeing” there are two versions of sight, of the visible. From sight and the visible. First version: I see from a distance, I perceive from a distance. I seize things, objects from a distance. It is well known that I don’t start by seizing them from within me to project them, I seize the thing where it is. Modern psychology taught us that. I perceive from a distance, I seize from a distance. And then, Blanchot tells us, there is another visibility, it is when distance seizes me. I am seized by distance. According to him, therefore, being seized by distance is the opposite of seizing at a distance. And, according to him, this is a dream. It is a dream that seizes me through distance. That’s what he calls it, when I’m seized by distance instead of remotely seizing, that’s what Blanchot calls fascination. I am fascinated. It’s the same thing: being seized by distance or seeing the image rise without resemblance are the same thing. Art and dream are exercises of sight.

So, my God, but my God, my God, what’s going on? What prevents Blanchot from saying “and vice versa”, since all of the elements are there? It’s curious and we are very surprised by that, because you have to see the text, and see if you have the same impression as me… He is about to say it, “and vice versa.” Well, no, he doesn’t say it and he won’t say it. He won’t say it, because—sticking to our method—because he can’t say it. He can’t say it because it would ruin everything he thinks. Why? Because if he moves onto the example of seeing he doesn’t address anything other than speaking, it only confirms what he just said about speaking. Namely: the adventure of the visible does nothing but set up the true adventure, which must be that of speech for Blanchot. Thus, the idea that there is also a superior exercise of sight is only there to a preparatory degree for the sole superior exercise which is speech as it speaks about what can only be spoken, that is… [Interruption of the recording] [2:02:13]

Part 4

… It’s the technical power, it’s even… it’s technically explained. The technical power to maintain a completely undetermined ground and to bring out a determination. What are [Francisco] Goya’s monsters? It is determination as it immediately comes out of an undetermined person that remains throughout. This is what Blanchot calls a true relation between the determined and the undetermined. A true relation in such a way that the indeterminate remains through determination and that determination immediately emerges from the indeterminate. A determination that immediately comes out of the indeterminate and remains under determination is what we call a monster. So, all right.

Well, we have the answer. In my opinion, Blanchot cannot say “and vice versa”. He can say “speaking is not seeing”, but he can’t say “seeing is not speaking”, because he has never conceived only one form – I’m not saying he’s wrong – he’s never conceived only one form, determination, the form of determination, that is, speech, the form of spontaneity, speech, and speech is related to the purely undetermined. So seeing will either slip into the purely undetermined, or will only be a preparatory step for the exercise of speech. We don’t need to see the difference with Foucault, it explodes, that’s all we did. It is enough to recall that, for Foucault, there are two forms, the form of the visible and the form of the statable. Unlike Blanchot, Foucault gave form to the visible. That is, for Foucault…you will tell me: this is tiny, I think this difference is very important, it is not tiny. For Blanchot, everything went through a relation of determination and pure indeterminacy. For Foucault – and thus he is Kantian and not Cartesian – everything passes through a relation of determination and the determinable, both having their own form. There is a form of the determinable, no less than there is a form of determination. Light is the form of the determinable just as language is the form of determination. The statable is a form, but the visible is also a form. Foucault, on the other hand, will be forced to add “and vice versa”, and the “and vice versa” is not a small addition, it is a reworking of Blanchot’s theme, “speaking is not seeing.”

But, as a result, it leads us to our third confrontation, because if Blanchot hadn’t dared “and vice versa”, if Foucault thus crosses the gap, the rift between two forms, the form of the statable and the form of the visible, the form of determination and the form of the determinable, and well, those who had done it before him, strangely enough, not strangely enough, were the ones who brought cinema to the powers of the audiovisual and of an audiovisual creator, and an audiovisual creator was not going to be an audiovisual ensemble, but on the contrary a distribution of audio and visual on both sides of a gap. And I say: well, that’s what defines modern cinema.

And as we saw last year, I’m just summarizing, I’m trying to summarize for those who weren’t here or to pick up from that discussion, because it matters a lot to me… Here too I would like to enumerate. So, first proposition, what is going on in these works that they do not attract many spectators, as we know, but that, at the same time, they are the ones who make true cinema today, uh, these works like those of Syberberg, Straub or Marguerite Duras. What strikes me immediately is that, I would say, it is a new use of speech, a new use of speech. This new use of the spoken word, it completely fits into our problem, why? Because for a very long time, at least on the surface, and this is not very complicated, but at least on the surface, speaking was like showing. And cinema became speaking in this form, speaking was really a dimension of the visual image. Speaking was just showing.

And, on the other hand, speaking could just not be seen, but at that moment, speaking was off-screen. Now the off-screen, the unseen, the unseen, the unseen speech, heard but unseen speech, the off-screen is a dimension of visual space. The off-screen is a dimension of visual space, since it is an extension of visual space outside the frame. So, we don’t see it, that’s not why it’s not visual. We don’t actually see it. But off-screen it can only be defined as that which goes beyond the visual framework. Under these two aspects, I can say that the first speaking in cinema was of the type “speaking is seeing”. Either the speech of people we see on the screen makes us see something, or speech off-screen, and the off-screen, and this speech, the voice-over, this off-screen speech comes to furnish the off-screen, the off-screen being a dimension of the visual. But that’s no longer what happens with the cinema I’m talking about, another formula emerges.