May 27, 1986

You wouldn’t confuse one of Mondrian’s lines with one of… of Kandinsky’s. Likewise, you do not confuse the concepts surrounding one philosopher with the concepts of another. Even if you can draw a connection between both of their concepts—just as you can between a painter’s lines and those of some other painter—I mean that major concepts are signed, and I see philosophy as a creative task. It’s a question of creating new concepts as they’re needed. Not according to social requirements but ones that are arguably deeper.

Seminar Introduction

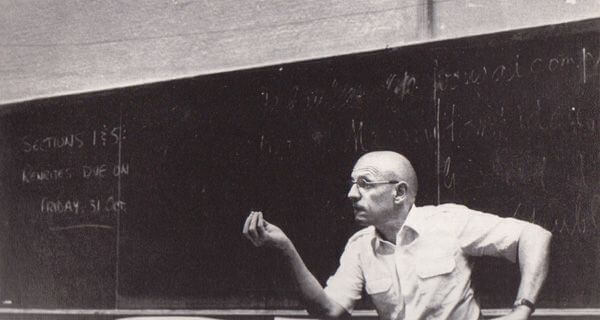

After Michel Foucault’s death from AIDS on June 25, 1984, Deleuze decided to devote an entire year of his seminar to a study of Foucault’s writings. Deleuze analyses in detail what he took to be the three “axes” of Foucault’s thought: knowledge, power, and subjectivation. Parts of the seminar contributed to the publication of Deleuze’s book Foucault (Paris: Minuit, 1986), which subsequently appeared in an English translation by Seán Hand (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

As the first of two “optional” end-of-semester sessions, here we have the “music session”, with an important focus on Pierre Boulez’s Pli selon pli (with two recorded parts played during the session and commentary from an unnamed seminar participant). After the considerable development of “line of the fold” in the Foucault seminar as well as in the Foucault book, Deleuze is here well advanced in preparing his analysis of the fold, and indeed, Boulez’s work and title, derived from Mallarmé’s poetry, will play a key, if somewhat understated role in Deleuze’s final seminar and next book, both on the fold and on Leibniz and the Baroque. Starting on what he meant previously by “interpretation” as related to the seminar on Foucault, Deleuze asserts that we have to draw the lines as the signature of philosophical concepts, hence indicating already his larger project, What Is Philosophy? However, with the session’s main focus on linking the concept of the fold and unfolding (le dépli) as an artistic gesture (cf. Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Mallarmé), Deleuze asks the unnamed presenter to offer selections from Pierre Boulez’s composition Pli selon pli, which incorporates selected Mallarmé poems, and to which Deleuze provides a reading of one of these poems. For Deleuze, this presentation provides evidence of thought’s relationship with art, particularly with the fold, not just in Mallarmé’s poetry (to which Deleuze refers in considerable detail). Deleuze also draws on the English essayist Thomas de Quincey and his book Revolt of the Tartars for additional support on this relationship. However, given the abrupt ending of the session, it is possible that the complete recording is missing.

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Foucault, 1985-1986

Part III: Subjectivation

Lecture 25, 27 May 1986

Transcribed by Annabelle Dufourcq; time stamp and additional revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Translated by Billy Dean Goehring; additional revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Part 1

… And I’m just coming back to my answer… the answer I gave to… to somebody… obviously, what I’ve offered you is an interpretation of Foucault’s thought.[1] But what do I mean by interpretation? For me, to interpret… I think it’s beautiful how Heidegger puts it, that all interpretation is an act of violence. For me, to interpret means, strictly speaking, two things. It means uncovering an author’s original concepts, and as I’ve often said, concepts are particular to philosophy no less than colors are to painting, or lines. You wouldn’t confuse one of [Piet] Mondrian’s lines with one of… of [Wassily] Kandinsky’s. Likewise, you do not confuse the concepts surrounding one philosopher with the concepts of another. Even if you can draw a connection between both of their concepts—just as you can between a painter’s lines and those of some other painter—I mean that major concepts are signed, and I see philosophy as a creative task. It’s a question of creating new concepts as they’re needed, not according to social requirements but ones that are arguably deeper.

Thus, to talk about a philosopher is necessarily to interpret them, to the extent that it involves drawing out the new concepts they were able to invent. These concepts are sometimes designated by well-known common nouns, despite having radically new meanings. Sometimes they’re designated by less familiar common nouns. By that I mean common nouns which take on new senses. Sometimes it’s necessary—but why is it suddenly necessary? We have to look in each case—sometimes it’s necessary to coin a word, a new name. So, I judge that this year, based on my own way of reading, we’ve covered a few concepts that I picked out as concepts original to Foucault.

The second way I understand “interpretation” is as mapping out the lines, following a certain order—this order can be very complex, but you have to choose one, at any rate—to map out the lines that tie these concepts together and to other concepts from other philosophers who are especially relevant to the philosopher under consideration. You see, for me… I say “for me” not because I feel I’m right but because I want to be clear—I’m not saying that everyone understands interpretation this way. For me, interpretation is absolutely not the search for what something means.

I understand interpretation to mean uncovering conceptual nodes, or conceptual creations,[2] and mapping out how concepts are connected to each other. So, maybe today and next time, for those who want to come… I think the only reason to come in would be if you had something to say about our work this year. There are two sorts of things you can bring me, plus whatever else you come up with. The first thing you can say is “Personally, I see things differently.” That is, you’ll say, “Foucault has some very original concepts that you’ve overlooked,” or “There are some links between concepts that you missed.” It might be on particular aspects or on the whole. Then I’d say you’d be offering a different interpretation.

And I believe that not all interpretations are worthwhile; an interpretation’s criterion, what makes it better than another, is its richness—it isn’t its inherent truth [but] its richness, its weight; it’s its weight. Just as one talks about the weight of a color, concepts have weight. You’d have to define a concept’s coordinates… I mean, if we’re talking about color, one talks about… about light, saturation, and weight. In music, you have other criteria. In philosophy, you’d have to define the coordinates of a concept. Are we talking about the concept’s weight like we talk about the weight of a color? Do we mean that a concept is saturated? Uh… so on, and so forth… But really, that’d be a different analysis.

So, of course what I want from you is to say, in general or in particular, not that “there’s something wrong” [with my account], since that’d hurt my feelings, but that there’s something important that I failed to see. That’s all. Well… but I’ll back up even further, while I have a few of you who—legitimately—understand interpretation totally differently and who’d say that my take on interpretation, as I’ve just tried to describe it, is insufficient and shouldn’t abandon the question “What does it mean?” For my part, you see, if I’m leaving the question, “What does it mean?” aside, it’s because “what it means” strictly depends on the novelty of the invented concepts and chains of concepts, and it will always mean [what it means] according to the concepts invented. That’s why I say that the true reversal, for me… in my opinion it holds for all philosophy, again, that concepts are signed. You can’t say “I think” without referring to Descartes and without drawing from Descartes’s world. And if you transform it as much as Kant did, then you create a new concept, but this new concept traces a line you have to account for: in what sense it derives from Descartes and in what way Kant transforms it. That means something very simple: proper nouns never designate people; proper nouns name operations, either of nature or of the mind. There is a lot to console us in that, since we are made of proper nouns, but we are not people… [Interruption of the recording] [9:00]

Part 2

… How do you recognize it? You recognize it by the need… Then, how do you recognize that it’s a new concept? It… How do you recognize concepts? … It comes back to working with coordinates. Thus, that’s what I want from you—maybe a little today and then next time. If you have nothing to say, then hey—I won’t have anything to say, either. So, we’ll meditate in silence. And then today… it’s just… yes, because there are some small things I had to skip, because I got too caught up in my schema last time… uh… I do have some things… so, a line, I said there was a line from Foucault between Foucault and Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, around this business of the fold and the unfold. I’d like to take this opportunity, perhaps, to say very briefly and even very vaguely since this is no longer my subject… you see that I already… I have nothing else to say, so uh… I’ll force myself a bit and try to discuss the relationship between this business of the fold and the unfold… well, it doesn’t seem to me very fundamental.

And… and well, in the same vein, I asked one of you who, by the way, suggested that we take a look at… Anyway, it’s someone contemporary with Foucault, Pierre Boulez… and who Foucault knew very well, and Boulez knew Foucault very well… There’s a piece or rather a set of pieces of Boulez which are titled Fold by Fold.[3] And I thought, hey now! If there was someone competent among us—and I have to say that this year we’ve had so many great talents… I’ve always been very pleased with Paris VIII audiences, but rarely do we have… I can now say at the year’s end that I’ve been teaching people of whom I feel most know Foucault’s writing as well as I do. That’s been very, very special to me and a sort of force…

But I was saying, we have this work, Fold by Fold, and Boulez borrows the expression, “fold by fold” from a poem by Mallarmé, and he calls it Fold by Fold and the pieces, this complex piece by Boulez, is built around three great Mallarmé poems, two to a lesser extent, right—yes?[4]

The presenter: [Inaudible comments; he explains the organization of Boulez’s composition in dialogue with Deleuze]

Deleuze: That’s it, yes, the title…

The presenter: [Inaudible comments]

Deleuze: Okay, yes—

The presenter: [Inaudible comments]

Deleuze: The three “Improvisations” …

The presenter: And the final piece is “Tombeau”…

Deleuze: Ah, I forgot “The Tomb” for [Paul] Verlaine![5] Uh… then, it’s not music based on a few Mallarmé poems, it’s… Few musicians, I think, have reflected as much as Boulez has on the musical text/poetic text relationship. So, when he borrows—we’ll see under what conditions—when he borrows from Mallarmé for the main title of this work, Fold by Fold, it must be noted that he takes it out of its context—the Mallarméan context being very interesting, we’ll see, but also very precise—no doubt, he removes it from its context… perhaps, perhaps it’s that he wants to highlight the fold of poetry and that of music; perhaps he wants to highlight something about the poem-music relationship. It’s not about adding something to Mallarmé’s poems, which weren’t lacking anything—Boulez is the first to realize it and to say it… Ah yes! It may be an operation, then, that would consist in a little folding—why? To what end? Maybe if we get a handle on that, we’ll have no problem jumping ahead, we’ll be able to jump ahead and recall some things Heidegger told us about the nature of the fold, since Heidegger’s the one who made the fold a philosophical concept. Which would let us come back to Foucault who, when he gets his hands on the notion of the fold, maybe handles it in another way that, by the way, wasn’t missed on either Boulez or Heidegger.

So, then I don’t at all know how it’s going to go, if it’s going to work, if we’re going to listen uh… You’ve chosen certain clips… What do you have in mind? Listen for a bit? And then you try to explain your selection…?

The presenter: [Inaudible comments] … to make a short presentation…

Deleuze: Okay, yes, yes.

The presenter: Fold by Fold is the title…

Deleuze: You speak loudly… I feel, so we’ll need for you and me to switch places… is that okay?

The presenter: [Inaudible] … I move there like that, I could….

Deleuze: Okay, yes. But if we can’t see you, we can’t hear you turned around; you can’t really hear someone from behind. You can do the opposite: have us listen first and then talk after. Maybe the shock of listening to it is good, too.

The presenter: [Inaudible; he speaks while changing places, hence a long pause, with noise of chairs and of students]

Deleuze: There, that’s good. [Pause] … We have the right… it’s private, right? It’s private; it’s not public. Anyway, surely … [Pause, sounds of participants] … And you have every right, if you find the music too beautiful, we’ll stop there, and we won’t talk anymore since … [Pause] [Brief interruption of the recording]

The presenter: We will begin with the first piece of [inaudible words]

Deleuze: “The Gift”, that is!

The presenter: The first piece, “The Gift of the poem”, from Mallarmé’s poem.

Deleuze: Right. For those who know Mallarmé, I’ll remind you, it’s “I bring you the child of an Idumean night” … [Pause] For those who don’t know this, [inaudible remark] … [Pause

[First movement: The Gift] [See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W56pQqEVetA] [18:52-34:10]

The presenter: So, this was the first movement. [Pause] … [indistinct words] a musical portrait of Mallarmé, [indistinct words] … This is a movement with a rather complicated genesis. [indistinct words; details on the development of this movement in the work]

[He then explains the musical and orchestral construction of the first movement as well as some details about the score] … It’s already deliberately structured by Pierre Boulez [indistinct words] … So, the first page can be considered as a page of declaration, in the first chord [indistinct words] …

So, the first verse, the first poem [indistinct words] … It’s the only time where Boulez allowed for us to hear the text perfectly to such an extent that there are [indistinct words] … The singer has the choice between talking in a low voice or [indistinct words] [Pause] … first part which shows his interest in leaving some room for chance, for the aleatory. [indistinct words] … And there, Boulez separated the three groups from one another, [indistinct words] … [He describes the function of each group, first the middle one, then the lower, then the upper] the much more eventful upper group with more agitated interventions. [indistinct words] … That poses enormous problems of [indistinct word] the score as the conductor [indistinct words] …

Boulez [indistinct word] enormously the different modes [indistinct words] of instruments. He is looking for the tones and sonorities of instruments for the way that Mallarmé sought out sonorities in words, [indistinct words] [He gives several details about the use of the instruments’ different capabilities within this process, with a reading of each instrument’s role in the movement]

A student: Did Boulez try to work with three sound groups or with [indistinct words] …, and what was the need for that? [Laughter; pause]

The presenter: I think that the need came from the fact that Boulez did not want a fixed organization like … [Pause] So, I’ll try to talk to you about this afterwards. [Pause]

[indistinct words] [He comments on the strong role of the piano] … and this part ends on a fermata [indistinct words] … and then we move on to the soprano’s return in the movement. So, there are so many verses here that aren’t borrowed from the poem, but only fragments [indistinct words] … Here as well, a good deal is left up to the soloist’s prerogative since [indistinct words] … and in the obligatory borrowings, she sometimes can choose between several solutions and it’s normally up to the instrumentalist to decide, up to the prerogative of soloist [indistinct words] …

The references are, in order, first, to the sonnet corresponding to “Improvisation III”, second, to the sonnet corresponding to “Improvisation II”, and third, to the sonnet corresponding to “Improvisation I”, and several pages further on, toward the end of this movement [indistinct words] … And “The Gift” ends with a third and final part which, there again, calls on the [indistinct word] choice of the conductor. The orchestra is divided in two levels: the upper lever and the lower level … [Pause; sounds of chairs, interruption in the presenter’s comments]

So, the orchestra is divided in two levels: the upper lever and the lower level, and the succession in the [indistinct words] … in five parts: A B C D E. So that gives us: in the upper part A B C D E [he writes on the board] and within this part [indistinct words], the conductor chooses the trajectory that he wants to take. Then, basically, there are some rules that intervene, that is, the whole of the [indistinct words] … necessarily, and the succession of letters in a line should be respected, that is, well, you can play A B; then, if you want to leave this line and go to A, you’re required to eventually work back up to C, but you can’t get to D or E. Thus, if one wants to [indistinct word], you’re forced to go back down to B, you can eventually play BC and climb up to D, and the two E parts are required to be played together. So, Boulez determined six possible trajectories by leaving it up to the conductor to choose which trajectory to carry out.[6]

Deleuze: I would just like…a side note… if you’ll let me? You find it…and you’ll find this everywhere in contemporary music—the blending of two sorts of rules. I’m trying to connect back up with our discussion. You constantly find in contemporary music the blending of actually binding rules with optional rules. On several points he’s already laid out certain rules for the singer: she can speak the lyric, she can sing it… There you have a very good example where you have a blend of rules in which some are binding, and some are optional. And that, in current music—I’m also thinking of [Luciano] Bério, for example—you find… Recall how, in a completely different context, of course, in Foucault, there is this game of binding rules and optional rules even at the level of statements. Yet this is a beautiful case of musical statements that present this complex of rules very different from each other. And that’s all I wanted to add…

The presenter: In Boulez’s work, in fact, optional rules are used, not in all of his works, but [indistinct words] he uses [indistinct words] … pure chance [indistinct words] …

Deleuze: Yes, never! Never.

The presenter: … in any event, to preserve the conductor’s or the soloist’s ability to choose, to make a certain number of possible choices, and I think that [indistinct words] … but the choice should be determined by a person; it’s not the intervention of pure chance [indistinct words] …

Deleuze: And it’s forced, eh? The difference—you’re absolutely right—the difference between Boulez and [John] Cage in this regard, it’s required; there can’t be pure chance… [Interruption of the recording] [55:37]

Part 3

Deleuze: What’s funny is that, at the same time, he moves back closer to Cage; this represents Boulez’s step towards… reunion with Cage.

A student: Can I ask a question?

Deleuze: Yes, yes, yes, yes!

The student: [indistinct words] When the soloist comes in, how can one know … [indistinct words]

The presenter: So, at the moment when there are [indistinct words] … the soprano comes back here, and on the previous page, Boulez marked [indistinct words] … in other words, the whole orchestra is then led by the conductor. So, at that point, the hierarchical organization can be respected. And then, when it comes to the soprano’s intervention, [Pause] she takes syllables from verses [indistinct words] … And there, she has a choice to make between three columns A, B, C … So, she has two required concerns: she must choose three syllables in the same column, either AAA, BBB, or CCC. But she has to distribute them… over time in two [indistinct words] … [Pause] She has an optional insert [indistinct words] … [Pause]

The student: [indistinct words]

The presenter: So, when she sings, she of course has her own line with precise notes to be sung…

The student: Her line is independent?

The presenter: Her line is independent. So there, the orchestra is no longer divided in blocs but is reunited, and at that point, there is [indistinct words] … a resonance that supports the soprano’s voice, at least makes the words more intelligible—not a lot, but more so than with the whole orchestra performing scattered sounds [indistinct words] … would mask the soprano’s voice.

The student: [indistinct words]

The presenter: To a certain extent, yes—ultimately, I’d say yes. In the end, one would have to ask Boulez [indistinct words] …

The student: [indistinct words]

The presenter: I don’t know, [Pause] that might be less clear, since the structures aren’t the same; there, it is the lyrics that intervene and… [indistinct word] of the soprano, whereas previously, the music is written out entirely, there aren’t [indistinct words] … movement between the three blocks, and in each case, [indistinct words] … [Pause] I was thinking that eventually there are [indistinct words] … to make some remarks about … [He explains to Deleuze what he hoped to present next]

Deleuze: I’d like to… we don’t have unlimited time, I mean, unfortunately; I’d almost like for you to choose another piece, if it were possible, another passage… Myself, I’m struck by this morning’s questions on the singer’s role that I think you only partially answered, since there are actually several instances in what you played for us… where the words… the point is that she casts words, and there are word-casting with very different functions uh… already it seems to me, in what you said and what you played for us, there is a lot… there is a lot to reflect on. So, I’d almost like, if you wouldn’t mind, for you to do the same thing, only with another piece. For you to forget those who are already interested or familiar, or what you can gather from reading Mallarmé’s poems, and so on. We’ll say what we have to for the books, the book that will help you, and so on… not difficult. So, we’ll act a little as though it said something differently to everyone. So, you take either “The Tomb,”[7] if you like, or something of… an “Improvisation” …

The presenter: I think we would have to listen to an improvisation,

Deleuze: That’s fine, it’s your choice.

The presenter: … regardless, because it’s delicate… we can bring together the orchestral movements …

Deleuze: Okay, which improvisation?

The presenter: So, “Improvisation I on Mallarmé”…

Deleuze Okay, is it “This virginal long-living lovely day”? That’s right, yes. [Pause]

The presenter: Well, I think it might be best to listen.[8] [64:15-64:50]

Deleuze [interrupting the recording]: Uh… could you… could you stop and rewind… is that possible?

The presenter: From the start?

Deleuze: No, no, no, no! It’s the tempo for me reading the poem because it really changes if you’ve… I’ll read it plainly, alright, so that you’ll hear the sonorities, otherwise it’s…

[Deleuze reads]

“This virginal long-living lovely day / will it tear from us with a wing’s wild blow / The lost hard lake haunted beneath the snow / By clear ice-flights that never flew away!

A swan of old remembers it is he/ Superb but strives to break free woebegone / For having left unsung the territory / To live when sterile winter’s tedium shone.

His neck will shake off this white throe that space / Has forced the bird denying it to face, /

But not the horror of earth that traps his wings.

Phantom imposed this place by his sheer gleam, / He lies immobile in scorn’s frigid dream /

Worn by the Swan dismissed to futile things.”[9]

There we are… now you might have a better idea… Let’s…

Deleuze: You already grasp—because the poem, “This virginal long-living lovely day,” is an extraordinary demonstration of voice, at the start…

[Transmission of the Boulez recording: see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I3lK4OJuGKw] [66 :40-72 :05]

The presenter: So, in this first improvisation, I’m going to try to see to what extent the form of Mallarmé’s sonnet influenced the improvisation’s musical form. To better [indistinct words] … of the score according to the organization into quatrains and tercets with interludes between each [indistinct word]. [Pause]

The divisions aren’t mine; it’s indicated on the score—it’s by Boulez. [He’s writing on the board as he speaks] The first quatrain, then, he puts at zero. At A, an instrumental interlude, interlude 1. At B, the second quatrain. At C, interlude 2. At D, the tercet. At E, interlude 3. [Pause, sound of students’ voices speaking] … At F, the second tercet. And at G, one can’t call it an interlude, but a coda, an instrumental coda. [Pause]

So, the divisions are very clean since, in the interludes, the voice doesn’t intervene at all, at any time. These are purely instrumental passages. So, if we follow the alternation, we can eventually divide the piece in two groups—one which would go from zero to C, the other which would go from D to G—which would each alternate between instrument-and-voice, instruments-only, instrument-and-voice, instruments-only. There’s the same alternance in the entire [indistinct word].

That’s one form of the whole piece’s organization. It’s one possible reading, but there are others. [indistinct words] … One can see the different parts as organized by tempo as a determining mode of organization. So, [indistinct words] … A B C D E F G [he draws on the board] So, at the top, to in moderate A; in B, very moderate; in C, very slow; in D, again, not too slow; [Pause] in E, moderate; [Pause]; in F, not too slow; and in G, very slow.

Then, with one exception, one could have another mode of organization, which would be the following: [indistinct words; he describes a different organization of rhythms] [Pause] So, the different parts [indistinct words] … Next, if someone is working on the instrumentation of the different parts, work undertaken by Dominique [indistinct name] in his work on Boulez, [indistinct words] … to distinguish four possible modes of instrumentation: he called the first alpha, instrumental [indistinct word] composed of [indistinct words] …; instrumentation beta which has vibraphone and harp in A, and vibraphone, harp, and gong in E; and instrumentation gamma is the most instrumental, without [indistinct words] …

So, if we drew up a third schema… can I erase one? [indistinct words] [Pause; he draws a new schema] … So, this organization would allow us to see the arch shape, rather traditional in [indistinct words] … [Pause] By taking middle part, C, as the peak of the arch, as the form’s culminating point, which is equally in relation with [indistinct words] … At this point, let’s still consider Part C as a coda, something not contradicted by the [indistinct word] of the score; it’s starting from [indistinct word] that the tempo becomes important, [indistinct words] … So, these different forms aren’t… they coexist. All readings are possible, [indistinct words] … the plurality of discourse that emerges. [Pause]

A student: [indistinct words]

The presenter: [indistinct words]

The student: That—it’s called improvisation”?

The presenter: It’s called “Improvisation I on Mallarmé”.

The student: [indistinct words]

The presenter: No, no, no, [indistinct words] … no room for randomness. Well, what it is, it’s that there are effectively two versions. A first version was presented in concert [indistinct words] … The grand version [indistinct words] … by Boulez so that it pairs with “Improvisation III” when the work is played in its [indistinct words] … In that case, there’s a correspondence. The first movement corresponds to “Tombeau” [fifth movement], “Improvisation I” goes with “Improvisation III” [indistinct words] …, and “Improvisation II” would be the center of the form [i.e. the arch]. But there isn’t any room for randomness.

The student: [indistinct words]

The presenter: Randomness [indistinct words] … [Pause]

Deleuze: I think that seems like enough, right? You’ve given us a very rich subject. A lot to think about.

The presenter: [indistinct words; he explains something regarding the presentation he’d planned]

Deleuze: Yeah, thankfully, because, if you had, it’s not what I wanted, in any case; what I wanted was for… nobody wanted that.

The presenter: That gives us something to think about…

Deleuze: Yeah, that’s exactly what I had in mind, and I think you did it very, very well, that is, we are all… thanks to you, we have material where we can… I wouldn’t dare say “analyze in a different way”—neither is it a question of analyzing it philosophically—but [we can] think about the subject with which I began: Fold by Fold. I’d almost say that we have a good case here, thanks to you.

But where are the folds? And what does it mean to “fold”? And what does it mean to “unfold”? What does “fold by fold” mean? What do “fold and unfold” mean as artistic or philosophical gestures? Personally, you know, it occurred to me, while I was listening, that somebody might be able to—it’s not my thing, I mean—but really, I wondered whether a Heideggerian could comment along these lines on Heidegger’s main take on the fold and the unfold; in other words, he could render it as a musical presentation. It should exist, after all, because some Heideggerian musicians uh… He is very close… I mean, a comparison between a great musician, for example, [Karlheinz] Stockhausen with Heidegger, would be as valuable as a comparison between Boulez and Mallarmé. Now, in my opinion, one would be surprised to see that, once again, the fold and the unfold are presented as creative acts… or something else, other operations, eh, other operations…. that’s what… So, at least you had something to add… thanks to you, we can dwell a little on this point.

The presenter: Well, this organization [indistinct words] … [He speaks about the organization of the final movement, “Tombeau”, then connects to another Boulez piece]

Deleuze: Yes, there, we don’t need to hear any more… I mean, with regard to the text you’re reading, we don’t need to listen to anymore. I mean it’s the text, Points de repère[10] … Right, yes, it’s the same text. Yes. Yes, yes, yes because he did it deliberately. The text is so far from the music that…

The presenter: [indistinct words]

Deleuze: Right, right.

The presenter: Otherwise, in [indistinct title], there’s an article by Foucault on Boulez.

Deleuze: Ah…. Tell us! Do you have it with you? Give us the rundown. Is it a long article?[11]

The presenter: No, there’s… a column.

Deleuze: You’ve marked the important passages? Is that it?

The presenter: [indistinct words]

Deleuze: Oh, it’s long. [Laughter] I mean, it’s long, it’s not… [Pause] You’ve read it… you have… do you have another copy, or is that your copy? Does it say anything essential?

The presenter: In this paragraph, here…

Deleuze: You found it?

The presenter: There’s something

Deleuze: This? This one?

The presenter: Yes, that one. [Pause; Deleuze prepares himself to read]

Deleuze: “During a time in which we were being taught the privileges of meaning, of the lived through [du vécu], the sensuous [du charnel], of foundational experience [de l’expérience originaire], subjective contents or social significations…” — See, this applies to everyone but especially to phenomenology — “[…] to encounter Boulez and music was to see the twentieth century from an unfamiliar angle—that of the long battle…” – Hey, a theme very dear to Foucault… — “that of the long battle around the ‘formal.’ It was to recognize how in Russia, in Germany, in Austria, in Central Europe, through music, painting, architecture, or philosophy, linguistics, and mythology, the work of the formal had challenged the old problems and overturned the ways of thinking. A whole history of the formal in the twentieth century remains to be done: attempting to measure it as a power of transformation, drawing it out as a force for innovation and a locus of thought, beyond the images or the ‘formalism’ behind which some people tried to hide it.” — He’s telling us that this formal is less formal than it seems — “And also recounting its difficult relations with politics” – Alright — “We have to remember that it was quickly designated, in Stalinist or fascist territory, as enemy ideology and detestable art.” — That’s funny — “Boulez only needed a straight line, without any detour or mediation, to go to Stéphane Mallarmé, to Paul Klee, to René Char, to Henri Michaux, and later to Cummings. Often a musician goes to painting, a painter to poetry, a playwright to music, via an encompassing figure and through a universalizing aesthetic. […] Boulez went directly from one point to another, from one experience to another, drawn by what seemed to be not an ideal kinship but the necessity of a conjuncture…”[12] That’s curious, eh? I think it’s a text of… transition from Foucault—what year is this?

The presenter: ’82.

Deleuze: ’82? That was quick! [Laughter] Let’s check… it’d be better for my case if it were ’72. [Laughter]

The presenter: ’82.

Deleuze: Okay, okay… You don’t always get what you want… So, there you have it. I’d like for you all to bear with me, in these final musings, since we’re putting everything together. This bit about music with Boulez, this folding business with Heideggerian ontology, this story… the movement of the fold and unfold in Foucault, with all the problems that entails… This article recalls the problem of thought’s relationship with art, with a possible glimpse at painting also… How do we sort it out? We aren’t even looking for coherence. First thing… uh, my first comment, is how I see it. The fold—I wouldn’t say that it’s a metaphor, but I would say that it’s a strong term. I don’t know if it’s metaphorical or not. It’s a strong term in… And how does it appear? What does the fold involve? As I see it, it’s that the fold concerns something that’s hidden at first glance. [Pause]

What does the folding? What does the folding is something that conceals and that folds in order to conceal. In this sense, it’s not only the curtain that will fold, it’s not only the lace that will fold like a so-called pleated curtain. But (even) the dust, the fog will fold. And after all, one of Mallarmé’s problems was that of presence and absence, an invocation to the fold, you’ll find it everywhere. Just like you constantly see lace, the fog, the fan that folds and unfolds. The movement of being folded, or the movement of folding and unfolding, is fundamental. And, if Boulez’s piece is called Fold by Fold, it’s due to a poem by Mallarmé of which I’ll read the first stanza: “At times” that is, at certain times… “At times, when no breath stirs it…”[13]

“At times, when no breath stirs it, all / The almost incense-hued antiquity / As I feel widowed stone let her veils fall / Fold by fold furtively and visibly / Floats or seems not to bring its proof unless / By pouring time out as an ancient balm.”

That’s it. Fold by fold, all the commentaries will tell you, but we can’t say, then, that we’re still dealing with the poem… what does that mean? It concerns Bruges, the famous city in Belgium, uh… and at times… at times, when no breath stirs it… That is, when there isn’t yet any wind, to put it plainly, early in the morning, before there is any wind. Well, there is the fog, which dissipates. The fog dissipates and “all the almost incense-colored antiquity,” that is, the “widowed stone,” that is, Bruges. Bruges the dead, Bruges the widow, begins to emerge as the fog’s folds come undone.

I mean… and at the same time, they “come to be” [se font] — what “comes to be”, right, the fog, you see, in certain hollows or at certain times, you have the impression that its folds come down just like the folds in a curtain. And that already takes us to something we cannot avoid… they’re fundamentally linked, the fold and something we see… what, that we see through the fold, to the extent that the fold comes undone… I don’t know what it’d require… We’d have to find just the right formula. Well, in relation to the fold or in the fold, something unfolds. If we say that, we’ve already stopped considering the fold and the unfold as two opposites. In the fold, something unfolds; Bruges emerges. In the fold of the fog, Bruges emerges.

A short work by Thomas de Quincey, famous 19th century English author, was recently translated, where there are… everyone has their favorite lines—I read it: a story about an Asian people, then a part of the Russian empire, who emigrate, who all pick up and leave, a big tribe… all leave the Russian empire and head back east. And the text is sublime. It’s called The Revolt of the Tartars. Editor: Actes Sud. And, in the end, we’re shown the place where they’re going to reach, through the catastrophes, they’ve overcome every catastrophe, and they arrive, and we see them arrive. We seem them arrive at their refuge. Listen to what it says: “There arose a vast, cloudy vapor.”[14] “There arose a vast, cloudy vapor […]. Through the next hour, during which the gentle morning breeze had a little freshened, the dusty vapor had developed itself far and wide into the appearance of huge aerial draperies…” “Through the next hour, during which the gentle morning breeze had a little freshened, the dusty vapor had developed itself far and wide into the appearance of huge aerial draperies, hanging in mighty volumes from the sky to the earth; and at particular points, where the eddies of the breeze acted upon the pendulous skirts of these aerial curtains, rents were perceived…”[15]

[End of the recording; given that this de Quincey text continues (see session 11 from the seminar on Leibniz and the Baroque) and also since Deleuze usually makes a final remark announcing the end of each session, it is possible that some of the recording is missing] [1:41:54]

Notes

[1] This was Deleuze’s response to a comment by Georges Comtesse the previous week, May 20, 1986.

[2] “Conceptual design” is a common translation for this phrase but given Deleuze’s frequent description of philosophy as a creative endeavor, “creation” might be more appropriate.

[3] The title is taken from a Mallarmé poem, “Remémoration d’amis belges”, of which Boulez makes no direct use. In the poem, the poet describes how a mist that covers the city of Bruges gradually disappears. Let us note that while we provide the translation of “pli selon pli” as “fold by fold”, the Tom Conley translation of this title and phrase in The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque is “fold after fold”.

[4] The composition is in five movements, the first and last using a line from a Mallarmé poem, the three middle movements using the entire text of a Mallarmé sonnet. The movements and their associated poems are: Don – “Don du poème”; Improvisation I sur Mallarmé – “Le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd’hui” ; Improvisation II sur Mallarmé – “Une dentelle s’abolit” ; Improvisation III sur Mallarmé – “A la nue accablante tu” ; Tombeau – Mallarmé’s poem of the same name. See also the discussion of Mallarmé, that this discussion in many ways prepares and announces, in session 9 of the Leibniz and the Baroque seminar, February 3, 1987.

[5] This refers to a commemorative poem (or “tombeau”) written on January 10, 1897, following the death of Verlaine.

[6] While the translation follows the text as transcribed, Deleuze and the presenter, in particular, refer to sheet music and/or other diagrams/notation of Boulez’s composition. Emily Adamowicz’s dissertation offers an excellent account of the “rotational array” described above; her work is replete with helpful diagrams and musical notation. Cf. Emily J. Adamowicz, “A Study of Form and Structure in Pierre Boulez’s Pli selon Pli,” Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 3133 (2015).

[7] This refers to the fifth movement of Boulez’s composition, one of several by Mallarmé.

[8] This is Boulez’s « Improvisation 1 on Mallarmé” corresponding to the Mallarmé poem that Deleuze reads immediately after.

[9] Stéphane Mallarmé, Collected Poems and Other Verse, trans. E.H. and A.M. Blackmore, introduction by Elizabeth McCombie (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 66-69.

[10] Presumably this refers to Pierre Boulez, Points de repère (Paris: Christian Bourgois, 1981).

[11] The selections that follow defer to Robert Hurley’s translation of the article, including his bracketed translation notes. See Michel Foucault, “Pierre Boulez, Passing Through The Screen,” trans. Robert Hurley, in Essential Works of Foucault vol. 2: Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology, ed. James D. Faubion (New York: The New Press, 1998), 241-244. The original text, “Pierre Boulez, l’écran traversé”, appeared in a collection edited by M. Colin, J.-P. Leonardini, et J. Markovits, Dix ans et après. Album souvenir du festival d’automne (Paris: Messidor, 1982), pp. 232-236; see also Dit et Écrits IV (Paris : Gallimard, 1994), pp. 219-222.

[12] See the Hurley translation, pp. 242-243.

[13] Mallarmé, 59-61. Translation slightly modified to accommodate Deleuze’s reading: e.g., “fold by fold” where the translator has it “fold on fold,” to reflect the typical translation for the title of Boulez’s piece. See note 3 on other variations of this expression.

[14] Reading the original English, one sees that Deleuze appears to omit nearly a page separating the arrival of the dust cloud and the line which begins “Through the next hour.” Cf. William Edward Simonds, De Quincey’s Revolt of the Tartars, Edited with Introduction and Notes (Boston: Athenaeum, 1899), 53-54. The ostensible omission is indicated in brackets; see also the analysis that Deleuze will present of this text in session 11 of the seminar on Leibniz and the Baroque, March 3, 1987.

[15] The French translation, which Deleuze reads here, has “the pendulous skirts” as “les plis.”

French Transcript

Dans la conférence du 27 mai 1986, Deleuze commence par expliquer ce que veut dire par «interprétation» par rapport à son cours sur Foucault. Les autres sujets de discussion comprennent: la création de concepts; la nouvelle acception des noms et des mots; les concepts originaux amenés par Foucault (Deleuze affirme qu’il en faut en tracer les lignes, la signature des concepts philosophiques); le pli et le dépli comme geste artistique; l’invocation du pli chez poète français Stéphane Mallarmé; et l’essayiste anglais Thomas de Quincey et son livre La révolte des Tartares. Une grande partie de la conférence consiste en l’écoute du compositeur, chef d’orchestre et écrivain français Pierre Boulez, Pli selon pli: Portrait de Mallarmé, qui incorpore des vers de la poésie de Mallarmé. Deleuze lectures aussi une partie de la poésie de Mallarmé.

Gilles Deleuze

Sur Foucault

3ème partie : Subjectivation

25ème séance, 27 mai 1986

Transcription : Annabelle Dufourcq (avec le soutien du College of Liberal Arts, Purdue University) ; l’horodatage et révisions supplémentaires, Charles J. Stivale

Partie 1

… Et je reprends juste la réponse… la réponse que j’ai faite à… à quelqu’un… : évidemment oui, c’est une interprétation de la pensée de Foucault que je vous ai proposée. [Il s’agit d’une réponse à un commentaire de Georges Comtesse, le 27 mai 1986] Mais qu’est-ce que je n’entends par interprétation ? Pour moi, interpréter… Je trouve beau le texte de Heidegger où il dit toute interprétation fait usage de violence. Pour moi, interpréter, ça veut dire, très strictement, deux choses. Ça veut dire : dégager les concepts originaux d’un auteur, car j’ai eu l’occasion souvent de vous le dire : pour moi, les concepts, [1 :00] en philosophie, sont aussi singuliers que les couleurs en peinture ou les lignes. Vous ne confondez pas une ligne de Mondrian avec une ligne de… de Kandinsky. De même, vous ne confondez pas les concepts qui renvoient à tel philosophe avec des concepts qui renvoient à tel autre, bien qu’entre les concepts de l’un et de l’autre, il peut y avoir des rapports tout comme entre les lignes de tel peintre et les lignes de tel autre peintre. Mais je veux dire, les grands concepts sont signés, et je vis la philosophie comme une besogne de création. Il s’agit de créer de nouveaux concepts suivant des nécessités, nécessités qui ne sont pas des nécessités sociales, qui sont sans doute [2 :00] de plus profondes nécessités.

Donc je dis : parler d’un philosophe, c’est forcément l’interpréter dans la mesure où c’est dégager les concepts nouveaux qu’il a su inventer. Ces concepts, parfois, sont désignés par des noms communs bien connus, et pourtant leur contenu est complètement renouvelé, parfois par des noms communs moins connus. Je veux dire : par des noms communs mais qui prennent une nouvelle acception. Parfois il y a nécessité, mais pourquoi une nouvelle nécessité ? Il faut voir dans chaque cas, parfois il y a nécessité de créer un mot, un nom nouveau. [3 :00] Donc j’estime cette année avoir proposé, suivant ma lecture à moi, un certain nombre de concepts que je désignais comme les concepts originaux apportés par Foucault.

Le deuxième sens de « interpréter » pour moi, c’est : tracer les lignes, suivant un certain ordre — cet ordre peut être très complexe, mais il y a de toute manière un ordre qu’il faut bien choisir — tracer les lignes qui unissent ces concepts entre eux et avec d’autres concepts d’autres philosophes avec lesquels le philosophe considéré a des rapports privilégiés. [4 :00] Vous voyez que, pour moi… Je ne dis pas ce « pour moi » avec le sentiment d’avoir raison, je le dis pour que ce soit plus clair, je ne dis pas que tout le monde comprend interpréter comme cela. Pour moi, interpréter ne signifie absolument pas chercher ce que ça veut dire.

Pour moi, interpréter signifie dégager les nœuds conceptuels, c’est-à-dire les créations conceptuelles et tracer les lignes qui vont d’un concept à un autre. Alors quand je dis, aujourd’hui peut-être et l’autre séance pour ceux qui voudront bien y venir… – je crois que vous n’avez de raison d’y venir que si vous avez quelque chose à me dire à votre tour sur notre travail de cette [5 :00] année. Vous pouvez avoir à me dire deux sortes de choses, plus celles que vous inventerez. La première sorte de choses que vous pouvez me dire c’est : moi, je vois les choses autrement. C’est-à-dire, vous me diriez : il y a des concepts très originaux de Foucault et t’es passé à côté, ou : il y a des liens entre concepts que tu n’as pas vu. Ça peut porter ou sur des points de détail ou sur l’ensemble. A ce moment-là je dirais : vous offririez une autre interprétation.

Et je crois que toutes les interprétations ne se valent pas, le critère d’une interprétation et ce qui fait qu’elle est meilleure qu’une autre, c’est sa richesse, [6 :00] ce n’est pas sa vérité par nature, c’est sa richesse, c’est son poids, c’est son poids tout comme on parle du poids d’une couleur il y a un poids du concept. Il faudrait définir les coordonnées d’un concept… je veux dire : si vous pensez à la couleur on parle de… de la lumière, de la saturation et du poids. En musique c’est d’autres critères. En philosophie, il faudrait définir des coordonnées d’un concept. Est-ce qu’on parle du poids du concept comme on parle du poids d’une couleur ? Est-ce qu’on peut dire qu’un concept est saturé ? … Tout ça, quoi… Mais enfin, ce serait une autre recherche, ça.

Donc ce que j’attendrai de vous, c’est évidemment que, ou bien sur le détail ou bien sur l’ensemble, vous disiez : eh ben oui, [7 :00] non pas « il y a quelque chose qui ne va pas », ça me ferait de la peine ; mais que vous me disiez : il y a encore quelque chose de mieux et tu ne l’as pas vu. Voilà. Ou alors… mais je ne recule encore plus, là, que je me trouve devant certains d’entre vous — et ce serait légitime — qui comprennent interpréter d’une tout autre manière et qui me disent que la conception que je me fais d’interpréter, telle que je viens d’essayer de la résumer, est une conception insuffisante qui ne doit pas laisser de côté la tâche de « qu’est-ce que ça veut dire ? ». Pour moi, vous comprenez, si je laisse de côté la tâche « qu’est-ce que ça veut dire ? », c’est parce que « ce que ça veut dire » dépend étroitement de la nouveauté des concepts et des enchaînements de concepts inventés et ça voudra toujours dire d’après les concepts inventés. C’est pour ça que je vous disais : un vrai [8 :00] renversement pour moi… ce que je dis vaut vraiment, à mon avis, pour toute la philosophie, encore une fois les concepts ils sont signés. Vous ne pouvez pas dire « je pense » sans vous référer à Descartes et sans le faire sortir du monde de Descartes. Et si vous le transformez autant que Kant le fait, à ce moment-là, vous créez un nouveau concept, mais ce nouveau concept a une ligne dont il faudra que vous rendiez compte : en quel sens ça dérive de Descartes et de quelle manière Kant le transforme. Ce qui veut dire une chose très simple à laquelle je crois : les noms propres n’ont jamais désigné des personnes, les noms propres désignent des opérations soit de la nature, soit de l’esprit. Il y a là toutes sortes de consolations pour nous car nous sommes des noms propres, mais nous ne sommes pas des personnes… [9 :00] [Interruption de l’enregistrement]

Partie 2

… A quoi vous le reconnaissez ? Vous le reconnaissez au besoin… Alors, comment on reconnaît que c’est un nouveau concept ? Ça… A quoi on reconnaît les concepts… ça renverrait au travail des coordonnées. Donc j’attends de vous cela, peut-être un peu aujourd’hui, et puis la prochaine fois. Si vous n’avez rien à dire, moi je n’aurai rien à dire non plus, hein. Donc, nous méditerons en silence. Et puis aujourd’hui… c’est juste… oui, parce que j’ai des petites choses que j’ai dû laisser tomber, parce que la dernière fois, mon schéma m’intéressait trop… J’ai des choses en effet… alors une ligne, la ligne que j’avais annoncée de Foucault entre Foucault et Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, autour de cette histoire du pli et du dépli. Je voudrais à cette occasion, peut-être, dire très rapidement et même très confusément parce que ce n’est plus mon sujet… vous sentez que j’ai déjà… je n’ai [10 :00] plus rien à dire, alors… C’est en me forçant un peu que je vais essayer de parler des rapports de cette histoire du pli et du dépli. Bon, ça ne me paraît pas très fondamental.

Et… Et puis, dans le même ensemble j’ai demandé à l’un d’entre vous, qui voulait bien, d’ailleurs, me le proposer en partie, que l’on se penche… C’est quand même quelqu’un qui est un contemporain de Foucault, Pierre Boulez… et que Foucault connaissait très bien et Boulez connaissait très bien Foucault. Il y a une pièce ou plutôt un ensemble de pièces de Boulez qui s’appellent « Pli selon pli ». [Le titre général de l’œuvre est emprunté à un sonnet de Mallarmé, « Remémoration d’amis belges », dont Boulez ne fait pas un usage direct] Et moi je me disais : tiens ! S’il y avait quelqu’un de compétent parmi nous, et je dois dire que, cette année, il y a eu énormément de compétents… J’ai toujours été [11 :00] très content du public de Paris VIII, mais rarement est arrivé… je peux le dire maintenant, c’est la fin de l’année que je fasse un cours devant des gens dont j’avais le sentiment qu’une grande partie connaissait les textes de Foucault aussi bien que moi.

Alors pour moi, ça a été très, très important, et ça a été une espèce de force… Mais je dis : voilà cette œuvre, « Pli selon pli », et Boulez, lui, emprunte la formule « Pli selon pli » à un poème de [Stéphane] Mallarmé. Et il l’appelle « Pli selon pli et les pièces », et cette pièce complexe de Boulez est faite autour de trois grands poèmes de Mallarmé, plus accessoirement deux, c’est cinq, je crois, hein ? C’est cinq. [12 :00] [La composition est en cinq mouvements, le premier et le dernier utilisant une ligne d’un poème de Mallarmé, les trois mouvements du milieu utilisant le texte entier d’un sonnet de Mallarmé. Les mouvements et leurs poèmes associés sont : Don – d’après le poème intitulé « Don du poème » ; Improvisation sur Mallarmé I – d’après le sonnet « Le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd’hui… » ; Improvisation sur Mallarmé II – d’après le sonnet « Une dentelle s’abolit… » ; Improvisation sur Mallarmé III – d’après le sonnet « A la nue accablante tu… » ; Tombeau – d’après le sonnet qui porte ce titre ; voir à ce propos la discussion de Mallarmé, que cette séance prépare, dans la séance 9 du séminaire sur Leibniz et le baroque, le 3 février 1987]

L’intervenant : [Propos audibles ; il explique la répartition de la composition de Boulez en dialogue avec Deleuze]

Deleuze : C’est ça, oui, pour le titre…

L’intervenant : [Propos inaudibles]

Deleuze : D’accord, oui…

L’intervenant : [Propos inaudibles]

Deleuze : Les trois improvisations…

L’intervenant : [Propos inaudibles]

Deleuze : Oui ?

L’intervenant : Et en dernière pièce, « Tombeau » …

Deleuze : Ah, j’oubliais le tombeau de [Paul] Verlaine ! [Il s’agit un poème après le décès du poète, écrit le 10 janvier 1897] [Pause] Donc, c’est non pas de la musique sur un certain nombre de poèmes de Mallarmé, c’est… Peu de musiciens, je crois, ont autant réfléchi que Boulez sur le rapport texte musical-texte poétique. Alors, quand il emprunte — on verra dans quelles conditions — quand il emprunte à Mallarmé [13 :00] pour en faire le titre général de cette œuvre, « Pli selon pli », il faut voir qu’il l’arrache à son contexte — le contexte mallarméen étant très intéressant, on le verra, mais très précis aussi — il l’arrache à son contexte sans doute… peut-être, peut-être est-ce qu’il veut marquer le pli du poétique et du musical, peut-être qu’il veut marquer quelque chose dans les rapports poèmes-musique.

Il ne s’agit pas, en effet, d’ajouter quelque chose aux poèmes de Mallarmé qui n’ont jamais manqué de rien ; Boulez est le premier à le savoir et à le dire… ah oui ! Il s’agit peut-être d’une opération, alors, qui serait un peu faire pli, pourquoi ? [14 :00] Dans quel but ? Peut-être que si on a une idée là-dessus, on pourra sauter, là, sans souci, on pourra sauter et se rappeler certaines choses que Heidegger nous disait sur la nature du pli, puisque c’est lui qui fait du pli un concept philosophique, Heidegger. Ce qui nous permettrait de revenir à Foucault qui, lui, quand il s’empare de la notion de pli, s’en empare peut-être encore en un autre sens qui n’ignore, d’ailleurs, ni Boulez, ni Heidegger.

Si bien qu’alors je ne sais pas du tout comment ça va se passer, si ça va marcher, si on va écouter… Tu as choisi certains moments… Comment tu conçois ? On écoute un bout ? Et puis tu [15 :00] essaies de dire pourquoi tu as choisi ça… ?

L’intervenant : [Propos indistincts] … faire une présentation rapide…

Deleuze : D’accord, oui, oui.

L’intervenant : Donc « Pli selon pli », c’est le titre…

Deleuze : Tu parles fort… j’ai l’impression, alors il faut que tu acceptes de venir à ma place et moi à la tienne… ça t’ennuie ?

L’intervenant : [Propos indistincts] … me mettre là-bas comme ça, je pourrais…

Deleuze : D’accord, oui. Mais si on ne te voit pas, on ne peut pas entendre, derrière, on entend très mal quelqu’un de dos. Tu peux faire l’inverse : faire écouter d’abord et puis parler après. Peut-être que le choc de l’audition est bien aussi.

L’intervenant : [Propos indistincts ; il parle en changeant de place, pause, bruits de chaises et des participants] [16 :00]

Deleuze : Voilà, c’est bien là. [Pause] On a le droit… c’est privé, hein, c’est privé, hein, ce n’est pas public. D’ailleurs, sûrement … [Bruits des participants] [17 :00] [Pause] … Et vous aurez tout droit, si vous trouvez la musique trop belle, on s’arrête, là, et on ne parle plus, puisque… [Pause] [Interruption de l’enregistrement] [17 :38]

L’intervenant : On va commencer par la première pièce de… [Mots indistincts] [18 :00]

Deleuze : C’est-à-dire, c’est « le Don » !

L’intervenant : La première pièce « Don du poème » de Mallarmé

Deleuze : C’est ça. Pour ceux qui connaissent Mallarmé, je le rappelle, c’est « Je t’apporte l’enfant d’une nuit d’Idumée » [Pause] … ceux qui ne le connaissent pas… [mots indistincts]

[Première pièce : Don] [18 :52-34 :05] [Pour voir cette pièce : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W56pQqEVetA]

L’intervenant : C’était donc la première pièce. [Pause] [mots indistincts] … un portrait musical de Mallarmé, [mots indistincts] … C’est une pièce avec une genèse un peu compliquée. [35 :00] [mots indistincts ; détails sur le développement de chaque pièce dans l’œuvre] [36 :00]

[Il explique ensuite la construction musicale et orchestrale de la première pièce, aussi bien que des détails sur la partition] [37 :00-38 :00] C’est déjà une volonté de la part de Pierre Boulez de structurer [mots indistincts] … Alors la première page, on peut la considérer comme page de déclaration, au premier accord [mots indistincts] … [39 :00-40 :00]

Alors le premier vers, le premier poème [mots indistincts] … c’est le seul moment où Boulez a décidé que l’on entendrait parfaitement le texte à tel point qu’il y a [mots indistincts] … La chanteuse a le choix entre parler à mi-voix ou [mots indistincts] [41 :00] [Pause] … première partie qui présente l’intérêt de laisser une certaine place au hasard, à l’aléatoire. [mots indistincts] … [42 :00] … Et là, Boulez a séparé les trois groupes les uns des autres, [mots indistincts] … [Il décrit la fonction de chaque groupe, celui du milieu et du bas, puis supérieur] et le groupe supérieur qui est beaucoup plus événementiel avec des interventions plus agitées [mots indistincts] … [Pause] [43 :00] Ça pose d’énormes problèmes de [mot indistinct] la partition comme chef [mots indistincts] … [44 :00] …

Boulez [mot indistinct] énormément les différents modes [mot inaudibles] des instruments. Il recherche les timbres et les sonorités des instruments pour la façon dont Mallarmé fait des recherches sur les sonorités des mots, [mots indistincts] [Il donne quelques détails sur l’emploi des capacités différentes des instruments dans cette recherche, avec une lecture du mouvement d’instrument en instrument dans la pièce] [45 :00-46 :00] …

Un étudiant : Est-ce que Boulez essaie de travailler avec les trois masses sonores ou avec [mots inaudibles] …, et quelle nécessité à ça ? [Rires ; pause] [47 :00]

L’intervenant : Je crois que la nécessité vient du fait que Boulez ne voulait pas d’une organisation fixe comme [Pause] … Alors, je vais essayer de vous le dire après. [Pause]

[mots indistincts] [Il commente le rôle fort du piano] [48 :00] … et cette partie se termine sur un point d’orgue [mots indistincts] … et on passe ensuite au retour de la soprane dans la pièce. Alors il y a tellement de vers-là qui ne sont plus empruntés au « Don du poème », mais seulement des fragments [mots indistincts] … [49 :00] Là également on a une part assez importante du libre-arbitre de la soliste puisque [mots indistincts] … et dans les emprunts obligatoires, elle a quelquefois le choix entre plusieurs solutions, et c’est normalement à l’instrumentiste de décider, au libre-arbitre de la soliste [mots indistincts] … [Pause] [50 :00]

Alors les emprunts sont successivement faits en premier au sonnet qui va donner l’Improvisation 3, en second au sonnet qui va donner l’Improvisation 2, et en troisième place, au sonnet qui va donner l’improvisation 1 et quelques pages plus loin, vers la fin de cette pièce [mots indistincts] … Et « Le Don » se termine par une troisième et dernière partie qui, là encore, fait appel aux choix [mot indistinct] du chef. L’orchestre est divisé en deux niveaux : [51 :00] le niveau supérieur et le niveau inférieur … [Pause, bruits des chaises, interruption dans le discours de l’intervenant]

Alors, l’orchestre est divisé en deux niveaux : le niveau supérieur et le niveau inférieur, et la succession dans les [mots inaudibles] … [52 :00] en 5 parties : A B C D E. Alors ça nous donne : à la partie supérieure A B C D E [il écrit au tableau] et à l’intérieur de cette partie [mot indistinct] le chef choisit le trajet qu’il décide d’effectuer. Alors, simplement, il y a quelques règles qui interviennent, c’est-à-dire que l’ensemble des [mots indistincts] … obligatoirement et la succession des lettres dans une même ligne doit être respectée, c’est-à-dire que, bon, vous pouvez jouer A B ici, vous êtes obligés, ensuite, si vous voulez quitter cette ligne de passer à A ici, vous pouvez éventuellement remonter à C, mais vous ne pouvez pas remonter à D ni à E. Donc si on veut [mot indistinct], on est obligé de redescendre à B, on peut jouer éventuellement B C et remonter à D, descendre à B, et les deux parties E se jouent obligatoirement ensemble. Alors Boulez a déterminé [53 :00] six trajets possibles en laissant au chef le choix du trajet à effectuer.

Deleuze : Je voudrais juste… une parenthèse… tu permets ? Vous le trouvez… et ça vous le trouvez constamment dans la musique contemporaine : le mélange entre deux sortes de règles. J’essaye de raccrocher à notre travail. Vous trouvez constamment dans la musique contemporaine le mélange entre des règles vraiment contraignantes et des règles facultatives. A plusieurs reprises, il a déjà fait appel à certaines règles facultatives de la cantatrice, elle peut prononcer le mot, elle peut le chanter… Là, vous avez un exemple très bon où vous avez un mélange de règles dont les unes sont contraignantes les autres sont facultatives. Et, ça, dans les œuvres de musique actuelle, [54 :00] je pense, par exemple, à [Luciano] Bério aussi, vous trouvez des…, vous trouvez des… Je vous rappelle comment, dans un tout autre contexte bien sûr, chez Foucault, il y a ce jeu de règles contraignantes et de règles facultatives au niveau même des énoncés. Or là, c’est un beau cas de ces énoncés musicaux qui présentent ce complexe de règles très différentes les unes des autres. Et c’est tout ce que je voulais ajouter…

L’intervenant : Chez Boulez, effectivement, on emploie des règles facultatives, pas dans la totalité de ses œuvres, mais [mots indistincts] il emploie [mots indistincts] … le hasard pur [mots indistincts] …

Deleuze : Oui, jamais ! Jamais.

L’intervenant : … de toute façon garder la possibilité pour le chef ou pour le soliste de choisir, de faire un certain nombre de choix possibles, et je crois [mots indistincts] … mais le choix doit être déterminé par une personne, ce n’est pas l’intervention [55 :00] du hasard pur [mots indistincts] …

Deleuze : Et c’est forcé, hein ? La différence, tu as complètement raison, la différence entre Boulez et Cage à cet égard, c’est forcé, il ne peut y avoir de hasard pur… [Interruption de l’enregistrement] [55 :37]

Partie 3

Deleuze : Ce qui est marrant d’ailleurs, c’est que, en même temps, il s’est rapproché à nouveau de Cage, ça représente un pas de Boulez vers… des retrouvailles avec Cage.

Un étudiant : Je peux poser une question ?

Deleuze : Oui, oui, oui, oui !

Un étudiant : [mots indistincts] [56 :00] Lorsque la soliste intervient, comment peut-on savoir… [mots indistincts]

L’intervenant : Alors au moment où il y a [mots indistincts] … la soprano rentre à nouveau ici, et la page précédente, Boulez a marqué [mots indistincts] … c’est-à-dire que tout l’orchestre est dirigé par le chef à ce moment-là. Donc l’organisation verticale [57 :00] peut être respectée à ce moment-là. Et alors, en ce qui concerne l’intervention de la soprano, [Pause] elle prend des syllabes de vers [mots indistincts] … Et, là, elle a un choix à faire entre trois colonnes A, B, C … Alors, elle a deux affaires obligés, elle doit prendre trois syllabes dans la même colonne, soit AAA, soit BBB, soit CCC. Mais elle doit les répartir … dans le [58 :00] temps en deux [mots indistincts] … [Pause] Elle a un insert facultatif [mots indistincts] … [Pause] [mots indistincts] …

Un étudiant : [mots indistincts]

L’intervenant : Alors, au moment où elle chante, elle a évidemment une ligne propre [59 :00] avec des notes précises à chanter…

L’étudiant : Sa ligne est indépendante ?

L’intervenant : Sa ligne est indépendante. Alors, là, l’orchestre n’est plus divisé en blocs, il est réuni, et on a à ce moment-là, [mots indistincts] … une résonance qui soutient la voix de la soprano, permet d’ailleurs une certaine intelligibilité du texte, pas énorme, mais elle est plus grande que s’il y avait tout l’orchestre jouant un son dispersé [mots indistincts] … masquerait la voix de la soprano.

L’étudiant : [mots indistincts] [60 :00]

L’intervenant : Dans une certaine mesure, oui ; enfin, moi, je dirais oui, enfin il faudrait demander à Boulez [mots indistincts] …

L’étudiant : [mots indistincts]

L’intervenant : Je ne sais pas, [Pause] c’est peut-être moins évident de dire ça, puisque que les structures ne sont pas les mêmes, là il y a d’abord le texte qui intervient [61 :00] et… [mot indistinct] de la soprane, alors que, auparavant, la musique est complètement écrite, il n’y a pas [mots indistincts] … mouvance entre les trois blocs, et dans chaque cas, [mots indistincts] … [Pause] Je pensais qu’il y a éventuellement [mots indistincts] … faire des remarques sur … [il explique à Deleuze ce qu’il avait espéré présenter]

Deleuze : Moi, je voudrais… on n’a pas un temps illimité, je veux dire, hélas, [62 :00] je voudrais presque que tu choisisses un autre morceau, si c’était possible, un autre passage… Moi je suis frappé sur les questions de ce matin sur le rôle de la cantatrice où je crois que tu n’as répondu que partiellement, parce que, en fait, il y a plusieurs cas dans ce que tu nous as fait écouter… où les mots… ce qui compte c’est qu’elle lance des mots et il y a des lancer de mots qui ont des fonctions très différentes… Déjà il me semble, dans ce que tu as dit et dans ce que tu nous as fait écouter, il y a beaucoup… il y a à réfléchir beaucoup. Alors je voudrais presque, si ça ne t’ennuie pas, que tu fasses la même chose pour une autre pièce seulement. Que tu laisses tomber : ceux que ça intéresse ou bien connaissent déjà, ou bien se renseigneront en lisant les poèmes de Mallarmé, tout ça. On dira tout ce qu’il faut [63 :00] pour les livres, le livre qui vous aidera, tout ça… pas difficile. Alors on fait un peu comme si ça disait quelque chose, inégalement, à tout le monde. Alors tu prends ou bien « Le Tombeau », [C’est-à-dire, le cinquième morceau dans la composition de Boulez] comme tu veux, ou bien quelque chose de… une « improvisation »…

L’intervenant : Je crois qu’il faudrait quand même écouter une improvisation …

Deleuze : Très bien, tu choisis…

L’intervenant : … parce que c’est délicat… on peut ramasser une des pièces orchestrales…

Deleuze : D’accord, quelle improvisation tu prends ?

L’intervenant : Alors, « Improvisation I sur Mallarmé » [mots indistincts] …

Deleuze : D’accord, c’est « Le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd’hui » ? C’est ça oui. [Pause]

L’intervenant : Bon, je pense que le mieux est peut-être de l’écouter… [64 :00] [Pause ; il s’agit de « Improvisation 1 sur Mallarmé » de Boulez qui correspond au poème que Deleuze lira tout de suite] [64 :15-64 :50] [Pause]

Deleuze [interrompant la diffusion]: Tu peux… tu peux arrêter et revenir… c’est possible ?

L’intervenant : Dès le début ?

Deleuze : Non, non, non, non ! Le temps que je lise le poème parce que ça change tellement si vous avez… [65 :00] Je le lis platement, hein, pour que vous saisissiez les sonorités, sinon c’est…

Deleuze lit :

Le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd’hui / Va-t-il nous déchirer avec un coup d’aile ivre / Ce lac dur oublié que hante sous le givre / Le transparent glacier des vols qui n’ont pas fui !

Un cygne d’autrefois se souvient que c’est lui / Magnifique mais qui sans espoir se délivre / Pour n’avoir pas chanté la région où vivre / Quand du stérile hiver a resplendi l’ennui.

Tout son col secouera cette blanche agonie / Par l’espace infligée à l’oiseau qui le nie, / Mais non l’horreur du sol où le plumage est pris. [66 :00]

Fantôme qu’à ce lieu son pur éclat assigne, / Il s’immobilise au songe froid du mépris / Que vêt parmi l’exil inutile le Cygne.

Voilà… Vous allez peut-être mieux saisir… Vas-y…

Deleuze : Saisissez déjà — parce que c’est extraordinaire comme travail de la voix, « Le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd’hui » au début. [Pour voir cette pièce : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I3lK4OJuGKw]

[Diffusion de la pièce : « Le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd’hui »] [66 :40-72 :05]

L’intervenant : Alors, dans cette première improvisation, je vais essayer de voir dans quelle mesure la forme du sonnet de Mallarmé a influencé la forme musicale de l’improvisation. Pour mieux [mots indistincts] … de [73 :00] cette partition suivant l’organisation en quatrains et puis en tercets avec des interludes entre chaque [mot indistinct]. [Pause]

Le découpage n’est pas de moi, il est indiqué sur la partition, alors il est de Boulez. [Il écrit au tableau en parlant] En zéro, donc, il met le premier quatrain. En A, [74 :00] un interlude instrumental, interlude 1. En B, le second quatrain. En C, l’interlude 2. En D, le tercet. En E, l’interlude 3. [Pause, son des voix d’autres étudiants qui lui parlent] … En F, le second tercet. Et en G ce qu’on appellera plus un interlude, mais ça fait une coda, coda instrumentale. [Pause]

Alors les séparations sont très nettes puisque, dans les interludes, la voix n’intervient pas du tout, à aucun moment. Ce sont des passages [75 :00] purement instrumentaux. Alors, si on respecte l’alternance, on peut éventuellement diviser la pièce en deux blocs, un qui irait de O à C, l’autre qui irait de D à G qui respecteraient l’un et l’autre l’alternance instrument-et-voix, instrument seul, instrument-et-voix, instrument seul. Il y a la même alternance dans toute la [mot indistinct].

Ça, c’est une forme d’organisation de toute la pièce, c’est une lecture possible, mais il y en a d’autres, [mots indistincts] … On peut prendre les tempi des différentes parties comme mode d’organisation déterminant. Alors, [76 :00] [mots indistincts] … A, B, C, D, E, F, G [il dessine au tableau] Alors en haut, alors en A modéré, en B très modéré, en C très lent, en D pas trop lent à nouveau, [Pause] en E modéré, [Pause] en F [77 :00] pas trop lent, et en G très lent.

Alors, à une exception près, on pourrait avoir un autre mode d’organisation, ce serait le suivant : [mots indistincts ; il décrit une répartition différente des rythmes] [Pause] Alors, les différentes parties [mots indistincts] … [78 :00] Ensuite, si on fait un travail sur l’instrumentation des différentes parties, travail qui a été fait par Dominique [nom indistinct] dans son ouvrage sur Boulez, [mots indistincts] distinguer quatre modes d’instrumentation possibles : alors, le premier, qu’il a appelé alpha, [mot indistinct] instrumental composé de [mots indistincts] … ; l’instrumentation béta qui est vibraphone et harpe en A, vibraphone, harpe et gong en E ; et l’instrumentation gamma, c’est le plus instrumental, [79 :00] sans [mots indistincts] …

Alors si on refait un troisième schéma… Est-ce que je peux en effacer un [mots indistincts] [Pause ; il dessine au tableau] … Alors, cette organisation permettrait de voir la forme en arche, assez traditionnelle en [mots indistincts] … [Pause] [80 :00] En prenant la partie C, médiane, comme sommet de l’arche, comme point culminant de la forme, qui est également en rapport avec [mots indistincts] … Considérons toujours à ce moment-là la partie C comme une coda, ce qui n’est pas démenti non plus par la [mot indistinct] de la partition ; c’est à partir de [mot indistinct] que le temps devient important, [mots indistincts] … Alors ces différentes formes ne sont pas … cohabitent. Toutes les lectures sont possibles, [mots indistincts] … [81 :00] la pluralité du discours qui apparaît. [Pause]

Un étudiant : [mots indistincts]

L’intervenant : [mots indistincts]

L’étudiant : Ça, ça s’appelle improvisation ?

L’intervenant : Ça s’appelle « Improvisation I sur Mallarmé ».

L’étudiant : [mots indistincts]

L’intervenant : Non, non, non, [mots indistincts] … pas de place à l’aléatoire. [82 :00] Bon, ce qu’il y a, c’est qu’il en existe, effectivement, deux versions. Une première version a été donnée en concert [mots indistincts] … La grande version [mots indistincts] … par Boulez de façon à faire pendant à l’improvisation 3 lorsque l’œuvre est jouée dans son [mots indistincts] … A ce moment-là, on a une correspondance. La première pièce fait pendant au « Tombeau », l’improvisation 1 fait pendant à l’improvisation 3 [mots indistincts] …, et l’improvisation 2 serait le centre de la forme. Mais il n’y a pas de place pour l’aléatoire. [83 :00]

Un étudiant : [mots indistincts]

L’intervenant : L’aléatoire … [mots indistincts] [Pause]

Deleuze : Moi ça me paraît suffisant, hein ? Tu as donné une très riche matière.

L’intervenant : [mots indistincts ; il dit qu’il n’a pas pu parler de tout ce qu’il voulait]

Deleuze : Ben, heureusement, écoute, parce que, si tu l’avais faite, ce n’est pas, en tout cas, ce n’est pas ce que je souhaitais, c’est ce que… personne ne souhaitait cela.

L’intervenant : … des éléments de réflexion…

Deleuze : Ben, c’est exactement ça, moi, que je souhaitais, et je crois que tu l’as très, très bien fait, c’est-à-dire, [84 :00] on est tous…, grâce à toi, on est devant une matière où on peut… je n’oserais pas dire « analyser d’une autre manière », il ne s’agit pas non plus d’analyser philosophiquement, mais il s’agit de rêver à cette histoire dont je partais : pli selon pli. Je dirais presque : là on a un bon cas, grâce à toi.

Mais où est-ce qu’ils sont les plis ? Et qu’est-ce que ça veut dire « plier » ? Et qu’est- ce que ça veut dire « déplier » ? Qu’est-ce que ça veut dire « pli selon pli » ? Qu’est-ce que veulent dire « plier et déplier » comme gestes artistiques ou philosophiques ? Car, moi, ce qui me frappait, tu sais, en t’écoutant, il y a un truc qu’on pourrait faire, ce n’est pas mon affaire, je veux dire, mais je me disais : un heideggérien [85 :00] pourrait commenter, vraiment, sur ce mode les grands thèmes de Heidegger sur le pli et le dépli, c’est-à-dire il pourrait en faire une présentation musicale. Après tout, ça doit exister parce que des musiciens heideggériens… Il est très proche… je veux dire, une confrontation d’un grand musicien, par exemple, de [Karlheinz] Stockhausen avec Heidegger, vaudrait bien une confrontation de Boulez avec Mallarmé. Or, à mon avis, on s’apercevrait avec étonnement, que là encore, il s’agit du pli et du dépli comme acte créateur… ou bien d’autre chose, d’autres opérations, hein, d’autres opérations… c’est ça que… Alors, à moins que tu aies quelque chose à ajouter… grâce à toi, on peut rêver un petit peu sur ce point.

L’intervenant : Bon, cette organisation, enfin, [86 :00] [mots indistincts ; il parle de l’organisation de la fin, « Tombeau », puis se réfère à une autre composition de Boulez] … [87 :00]

Deleuze : Oui, là, il ne faut plus l’écouter, lui… Je dis : quant au texte que tu dis, il faut plus l’écouter, lui. Je veux dire c’est le texte de « Point de repère » que tu… [Référence sans doute à Pierre Boulez, Points de repère (Paris: Christian Bourgois, 1981)] … C’est ça, oui, c’est le même texte. Oui. Oui, oui, oui parce qu’il l’a fait exprès. Le texte est tellement en retrait sur l’œuvre que…

L’intervenant : [mots indistincts]

Deleuze : C’est ça, c’est ça, c’est ça.

L’intervenant : Sinon, il y a dans [mot indistinct] un article de Foucault sur Boulez… [88 :00]

Deleuze : Ah… Raconte ! Tu l’as, là ? Raconte les points. Il est long, cet article ? [Il s’agit d’un écrit de Foucault « Pierre Boulez, l’écran traversé », paru dans Dix ans et après. Album souvenir du festival d’automne, éds. M. Colin, J.-P. Leonardini, et J. Markovits (Paris : Messidor, 1982) pp. 232-236 ; voir Dits et écrits, IV (Paris : Gallimard, 1994), pp. 219-222]

L’intervenant : Oh non, il y a … une colonne.

Deleuze : Tu as marqué les passages importants ? C’est ça ?

L’intervenant : [mots indistincts]

Deleuze : Oh, c’est long. [Rires] Je veux dire : c’est long, oui, ce n’est pas… [Pause] Toi qui l’as lu… tu l’as… tu as un autre numéro ou c’est ton numéro, ça ? Est-ce qu’il dit quelque chose d’essentiel ?

L’intervenant: Dans ce paragraphe-là, là…

Deleuze : Tu as trouvé ?

L’intervenant : Il y a quelque chose.

Deleuze : Ça ? Celui-là ?

L’intervenant : Oui, celui-là. [Pause, Deleuze se prépare à lire] [89 :00]