March 11, 1986

For each historical formation, I have as first question: with which forces coming from the outside do the forces in man – that’s right, ‘the forces in man’ and not ‘forces of man’ – do the forces in man enter into relation? Second question: once this relation of forces is assumed, what form follows from it? … In certain cases, this can be the form man. I would say that, at that moment, the form ‘man’ follows from the relation of forces in man with other forces coming from outside, without specifying which. This implies that … in other formations, the forces in man enter into relation with other forces coming from outside, but the composite is a form which is not that of man, which is not man. Hence, you understand, following such a method, it goes without saying that the form ‘man’ has not always existed and will not always exist. The form ‘man’ is the composite of forces in man with the forces coming from outside under a certain historical formation. But under other historical formations, the composite form will not be man, it will be something else.

Seminar Introduction

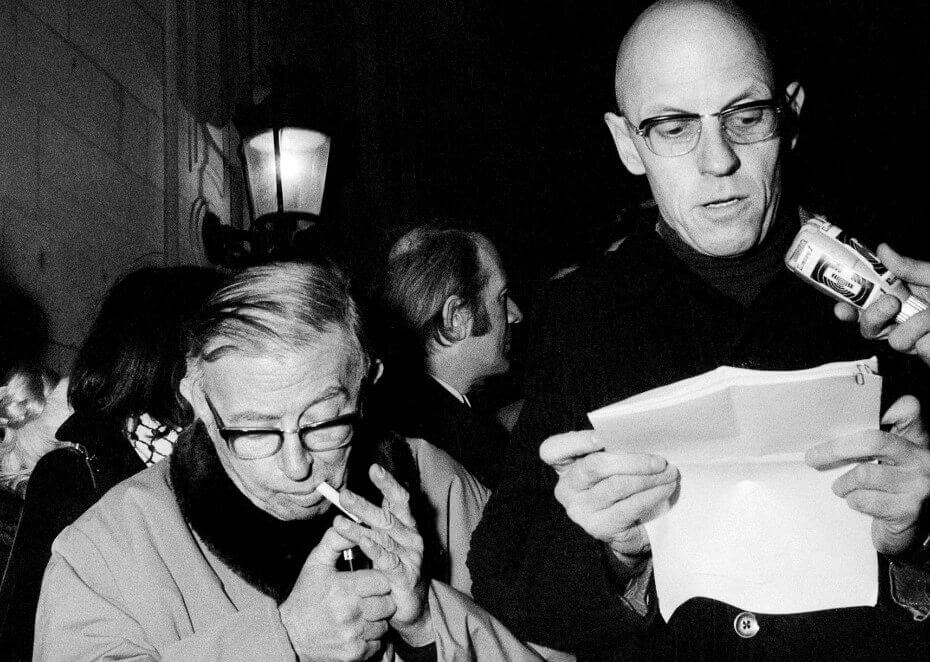

After Michel Foucault’s death from AIDS on June 25, 1984, Deleuze decided to devote an entire year of his seminar to a study of Foucault’s writings. Deleuze analyses in detail what he took to be the three “axes” of Foucault’s thought: knowledge, power, and subjectivation. Parts of the seminar contributed to the publication of Deleuze’s book Foucault (Paris: Minuit, 1986), which subsequently appeared in an English translation by Seán Hand (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

Deleuze continues examining how Foucault traces three “ages” in The Order of Things (begun in the previous session), seeking to address the distinction between life as infinite and life in its finitude. Thus, in the Classical Age, these are the forces of elevation to the infinite (cf. Pascalian anxiety, which Deleuze calls a thought of unfolding (le dépli), and he offers the handy formulation: “force in man + forces of elevation to the infinite yield as composite the ‘God-form’”. Then, continuing to the next “age”, the nineteenth century, with the triple forces of finitude in life, language and labor, that is, a thought of re-folding (repli), Deleuze again notes that the Kantian revolution inspired Foucault to see the nineteenth-century transformation as replacement of the originary infinity with a constitutive finitude, man first encountering the exterior forces of finitude (life, language, labor), and then making finitude his own. The rest of the session is devoted to tracing how these two moments are developed in the successive formations on specific issues: questions of life (Jussieu, Lamarck, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Cuvier, and Darwin), questions of death (Bichat), labor (Adam Smith, Marx and Engels, and David Ricardo) and grammar and philology (Bopp and Schlegel). Each formation corresponds to developments of pleating and folding, leading Deleuze finally to consider a third formation (with Nietzsche, the figure of the Overman), with the “death of man” question which, for Foucault, simply means that the “man-form” is no longer comprehensible to contemporaries, an age of genetic code, cybernetic machines, the revenge and rise of silicon, with which the forces of man now enter into contact, unleashing an “unlimited finite”. Concluding with the poetic vision of Rimbaud’s “Letter of the Seer”, Deleuze suggests that this formation’s “Overman” is charged with rocks, animals, and literature.

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Foucault, 1985-1986

Part II: Power

Lecture 15, 11 March 1986

Transcribed by Annabelle Dufourcq; time stamp and additional revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Translated by Christian Kerslake; additional revisions and time stamp, Charles J. Stivale

Part 1

[Noises of students and several vague words from Deleuze] … I begin with a delicious activity, an autocritique. Because I was truly unhappy with the second part of our preceding session. So, what made it no longer work all of a sudden? Obviously, it was not your fault, it was mine. Note that this is the charm of courses; one believes one is relating to something very well, and then it does not work, it undoes itself. Everyone who does courses must have had this experience. Sometimes, happily, it is the opposite. One believes one doesn’t relate to something and then it works, and it forms as one is speaking. It is curious, that; but in fact, for myself, I was rather … in the second part of last time, I was rather in the other position.

I thought I was grasping it well and then: nothing at all. It derailed, it derailed. Then I said to myself: why? Despite everything, why? What happened in this second half? The first half, for me, worked. That is also the charm of courses – I signal it to you but you all know it – it is that whoever does a course doesn’t have quite the same point of view as the one who listens, to the extent that, while I’m doing a course, which is a strong moment for me, for many of you, on the contrary, it could very well be a weak moment; and inversely, what would be a strong moment for you, for me will be… [Deleuze does not complete this] I think that this is what makes the activity of the course interesting, and not at all of the same type as a book and reading a book.

So anyway, I asked myself: what has happened so that I derail like that and lose my thread? And I said to myself that I had perhaps attempted …, that this was perhaps what eluded me, I had attempted to systematise something that Foucault had not wanted to systematise. And that therefore I had massively hardened positions which …, for reasons that I will to try to seek, positions which were, in Foucault, completely supple, all in their evocation, and that I myself had made too much of concepts, very assignable concepts, and that at that moment, there was a hardening that had made it so that I could no longer cover the totality of the texts about which I was thinking. This is to say that it is not the having systematised which was bad, it was having systematised at the moment when it was not necessary, on points where it was not necessary.

Hence it seems to me now that a certain number of things were valid in what I said last time – for me anyway, you can discuss your opinions afterwards – a certain number of things were valid and others were not. So, I am forced to start again because one cannot base oneself on a stew like that of the last time. I am forced to start again and try to better mark the places where one can systematise, and those where on the contrary, it is necessary to let very fluid kinds of currents flow. It is so fluid, – in this regard, not always, but on this point – Foucault’s thought is so fluid that, in my commentary, I sometimes had the air of contradicting the letter of Foucault. For example, Foucault talks from time to time of the infinity of life. For myself, on the contrary, I strongly insist on this: that in Foucault’s thought, life is a force of finitude. I don’t think this is serious; for example, when he talks of the infinity of life, it is in a sentence implying through its context that one can in a certain sense talk of the infinity of life, but this doesn’t rule out that, in its most fundamental force, life is finite, there is a finitude of life.

So, it seems to me that one must distinguish those places where there is a simple supple expression, and the places where, on the contrary, the expression becomes very categorical. And last time I was not given the means to bring about such a distinction. Thus, once again, the necessity of recommencing certain points and of being …yes.[1]

And there is one thing that is left over from what we did last time. What is left over is the general problem, “relation of forces to forms”. And this relation is presented in the following manner: the forces are always a complex, that is, a set of relations of forces with force. There is always a relation of forces in the plural.

Hence our first question is: assuming a historical formation, the forces in man – I explained that last time, that’s valid – the forces in man necessarily enter into relation with the forces of the outside. Which forces? Observe: in every assignable historical formation, the forces in man enter into relation with forces come from the outside. But, depending on the formation, they do not enter into relation with the same forces. Therefore, the forces of man will enter into relation sometimes with some forces, sometimes with other forces, coming from outside. So that, for each historical formation, I have as first question: with which forces come from the outside do the forces in man – that’s right, ‘the forces in man’ and not ‘forces of man’ – do the forces in man enter into relation?

Second question: once this relation of forces is assumed, what form follows from it? What form follows from it? In certain cases, this can be the form man. I would say that, at that moment, the form ‘man’ follows from the relation of forces in man with other forces come from outside, without specifying which. This implies that, in other cases, that is, in other formations, the forces in man enter into relation with other forces come from outside, but the composite is a form which is not that of man, which is not man.

Hence, you understand, following such a method, it goes without saying that the form ‘man’ has not always existed and will not always exist. The form ‘man’ is the composite of forces in man with the forces come from outside under a certain historical formation. But under other historical formations the composite form will not be man, it will be something else. One had an experience of it – I’m summarising – because it still held; one already had an experience of it during the classical formation. The classical formation, in the classical age, considers forces in man, but these forces in man enter in relation with which other forces from outside? I would say: they enter into relation with all the forces of elevation to the infinite. And what is that, a “force of elevation to the infinite”?

Concretely, that means what? It does not matter where this force is. I would say … Perhaps it is the force of representation. And it would perhaps be a possible definition of representation to say: to represent is to give oneself the possibility of elevating to the infinite. That would be what representation is. At least it would be a definition, it is difficult to define representation. It is necessary to see if this would not be a possible definition, a valid definition: to represent oneself is to elevate something to the infinite, or to grasp something that is subsequently represented as being capable of being raised to the infinite. There is not one force alone of elevation to the infinite. Why is that? Because there are orders of infinity. We saw that last time: there is an infinity through itself, for example, which cannot be confused with something which is only infinite through its cause. There is an infinitely large, but there is also an infinitely small: there are orders of infinity. These orders of infinity are not indeterminate, they are hierarchised.

Why? Since they tend towards the most perfect infinity, that is, infinity through itself. And I would say: if you try to define the thought of the 17th century, it seems that it is that. The thought of the 17th century is a thought which fundamentally thinks the infinite and the orders of infinity. And the problem of man in the 17th century is: man is lost in the orders of the infinite. That will burst through with Pascal. And I would say to you: there …, as a matter of fact one will see that in the method of Foucault it is very important to break false lineages. … Whatever the greatness of Pascal for us today, there is no reason to make a lineage from Pascal to certain contemporary authors that would be illegitimate. Pascalian anxiety is an anxiety in relation with the infinite and the orders of the infinite. Where is man in all these orders of infinity? Where is a place to be found for man, if every time one assigns a place, this place slips away in favour of an infinite? Man is decentered for Pascal because, fundamentally, he is swept up in orders of the infinite: the infinitely large, the infinitely small.

When I say: when the forces in man enter into relation with the forces of elevation to the infinite, which are both very different from each other, very divergent, but which all converge towards God, the form composed by this ensemble of forces (forces in man and forces of raising to the infinite), this means what? This is not man; it is God. The form composed by this ensemble of forces, it is God. Hence the idea that in the classical age the form ‘man’ strictly speaking has no place for the simple reason that the infinite is always first in relation to the finite. It has so little place that the forces in man only compose themselves in order to compose something other than man, since they themselves enter into relation with forces that raise it to the infinite. The forces in man, these are understanding and the will, and regarding these the philosophers of the 17th century will say to us: yes, but the human understanding is finite; if one raises it to the infinite in order to isolate it at the level of the infinite, once it is said that perfection is what can be raised to the infinite, then one has the divine understanding, which is itself infinite. And the human understanding is only a limitation, the human understanding is only a limitation of the divine understanding

Hence at all the levels of the thought of the 17th century, this means what? This is perhaps what I did not know how to do last time, to finally isolate the essential concept, or what revealed itself to be the essential concept. To say the forces in man enter into relation with the forces of elevation to the infinite is to say what? It is to say that everything which presents itself will develop itself, will deploy itself, will deploy itself to the infinite and in a continuous manner. The knowledge of the 17th century will constitute itself through tables, tables in which will take place … continuous tables, in which every thing, every being, will take its place, in a kind of deployment to the infinite. The thought of the 17th century will be fundamentally a thought of the unfold [dépli], of deployment, of development.

Thus, the analysis of wealth will develop itself in a kind of table, the table of wealth. The analysis of the living being will develop itself in a kind of table of organic characters which will form a continuous series, the continuous series according to which each living being takes its place. And the continuity of the series is a fundamental character because it is its order of infinity for it [c’est son ordre d’infini à elle], it is its order of infinity for it. And I insist on that because perhaps then we touch on a word that we constantly come across in all of Foucault’s work: the idea or the hypothesis of an unfold of things and beings. To unfold, to develop. The unfold is a word which returns constantly, constantly.[2]

But, at the point we have reached, you can see how that word is inscribed in the thought of the 17th century. Classical thought unfolds things and beings according to continuous series which mark the order of infinity proper to creatures. And it has often been noted that, for example, natural history in the 17th century does not content itself with being systematic. By ‘system’ one must understand the distribution of identities and differences in the living being. What is identical? What is different, etc? But the system itself develops itself in series and the series is something specific, consisting in the arrangement of living beings in an order such that, through little differences, one passes from one to another according to an order of continuity which is an order of infinity of the creature, of the infinity of the creature. Thus, the theme that from that moment the analysis of wealth, natural history, and the analysis of discourse or general grammar will proceed though continuous tables, capable of being prolonged to the infinite.

The thought of the 17th century is a thought of deployment and of the unfolded. One unfolds things and beings and, through that, in unfolding things and beings, one forms the continuous series of things and beings. Fine, I don’t want to say anything more about that because everything that I said last time in this regard seems to be of value and it is this notion of the unfold that seems to me fundamental. Good. Why? We do not yet know why it should be fundamental. I simply observe that if the idea of the unfold appears when Foucault analyses the thought of the 17th century, is it by chance that the same word appears in every other context and runs through all Foucault’s work?

I pass then to the other formation. I would therefore say: the forces in man … the formula of the classical age according to Foucault, would be: the forces in man enter into relation with the forces of infinity, and, from that moment, all together they compose what? They compose the idea of God and not the form ‘man’. You will say to me: But how can one say that God is composite? Thus, I correct myself by saying ‘the idea of God.’ God is without doubt, as all the authors of the 17th century remind us, an unfathomable unity. But what precisely does that mean, unfathomable unity? That doesn’t stop his idea from being composite. What composes the idea of God for an author of the 17th century? We know the answer: all the perfections capable of being raised to the infinite. Everything which is capable of being raised to the infinite can be related to God.

In other words, God is composed, or rather the idea of God is composed, by all the forms, as they say – it is an expression of Leibniz himself – by all the forms taken absolutely, that is, independently of their limits. Hence the problem for the 17th century — it is interesting to know why something was a problem in one epoch and, perhaps, is no longer one today — the problem in the 17th century was: is the extended a property, an attribute, of God? Good. The answer is simple. It depends. Necessarily, it depends. If you can extract from the extended something of the infinite, then, yes, the extended is an attribute of God. If you cannot, that is, if the extended is inseparable from its limitation, if the extended only participates in inferior orders of infinity, for example, the indefinite, if it only participates in inferior orders of infinity, it cannot be infinite through itself, and consequently it is not attributable to God.

It follows that it would be stupid to say: in the 17th century certain authors attribute the extended to God and others refuse to attribute the extended to God. What must be said is that, in the 17th century, all the authors who think that there is in the extended something of the infinite properly speaking, attribute it to God; while all those who think that the extended is inseparable from its own limitation refuse the attribution to God. Descartes will refuse the attribution to God, but Malebranche and Spinoza, in two very different ways, who discover in the extended something of the infinite-through-itself, that is, an infinity of the first order, attribute it necessarily to God. At that point what is concerned is an indivisible extension, infinite, which from that moment forms part of the attributes of God. There you go. What’s happening? — You’ll be interrupting me, ok, if there’s something that’s not right because I’d like… Is there something that’s not right?

A student: [Inaudible comments]

Deleuze: What?

The student: [Inaudible words] … one can have also a form which is the form of man?

Deleuze: Not in that case, but in another formation. And with other forces.

The student: When one thinks force in man, it is indeed necessary to think a form of man.

Deleuze: No.

The student: [Inaudible words] … that is what I don’t understand.

Deleuze: No, no. If not, all will be lost. We have seen …

The student: [Inaudible comment]

Deleuze: No! One does not presuppose! If one presupposes, because everything is mixed in … of course, one can make assumptions [supposer] … but this is not what counts. What counts is the difference of nature between the level of forces and the level of forms. And we have seen that from the beginning. Forces, they are informal. So, when I say ‘the forces in man’, that has the air of presupposing the form ‘man’. No! I do not presuppose at all the form ‘man’, I just consider the forces which, as such, are called human. “Are called human”, you will say, that assumes … Because they are not in animals. They are … good …, it is as if they are the place of the space of forces, for example, I say: understanding, the will. I do not presuppose at all a form of man, I take understanding as a force, I say ‘It is a force in man’. The fact is that animals … good, good. I take, if you like, I can consider man as …, at this point, if you say to me ‘that presupposes man’: no!

I define man as a type of forces and uniquely a type of forces, and I ask: these forces, for example understanding and will, which I call forces in man or human forces, because they do not present themselves amongst the animals, because they distinguish themselves, they occupy a certain region in the field of forces, I say: with which other forces do they enter into relation? In the 17th century, with the forces of elevation to the infinite, hence: the understanding will only be a limitation of infinite understanding. And, at this point, the composite is not man, it is God. You see: forces in man + forces of elevation to the infinite yield as composite the God form, the composed form God. And if someone says to me, here again, God is not composite, I say: yes, God is not composite, but his form is composite, that is, his presentation is composite. If I summed everything up, I would say: the 17th century is the age of representation… [Interruption of the recording] [31:42]

Part 2

… So let us pass to the following formation. The 19th century: what happens? Which mutations, since we have seen that every relation of forces implied a type of diagram? The diagram is the statement of relations of forces, it does not engage any form yet. There has been a mutation of the diagram. The diagram of classical thought is, once again, the force in man that embraces the forces of elevation to the infinite. In the 19th century formation, what happens? The forces in man come up against and embrace the forces of finitude. What are these forces of finitude? According to Foucault, they are triple: life, language, labour.

You say to me: but life, labour, language existed in the 17th century … That is not the question. They existed, yes, but labour was dissolved in the series of wealth, in the table of wealth. Life was as if developed, deployed, in the continuous series of natural history. That was what counts. You sense immediately where I want to get to. It is that here one will find oneself before what? The inverse phenomenon, the inverse category. The whole thought of the 19th century will be a thought of the finite, of re-folding [repli]. The forces in man refold themselves onto the forces of finitude. They fall back on the forces of finitude. A folding [pliure], a pleating [plissement] is produced. The forces in man are refolded around the forces of finitude. They refold themselves, they fall back on the forces of finitude. If I insist on that, it is because, no less frequently than the word ‘unfold’ [dépli] in Foucault, you find, throughout his work, ‘fold [pli]’, ‘folding [pliure]’, ‘bending back [pliage]’. This is another pole.

But no doubt, just as it is constant in all his books, it is the basis of all his metaphors. I believe the metaphors of Foucault are like … that they truly have the unfold and the fold as their matrices. Why is this important to me? For reasons that cannot be understood at this point. For you can sense that this will be a necessary moment of a confrontation to come, when we will inquire into the precise nature of the relation Foucault-Heidegger. For it has long been the case that Heideggerian thought has been presented as a thought of the fold. And what is Being according to Heidegger? Well, Being is precisely the fold. It is the fold of Being and beings. Being [L’être] is indissociable, inseparable, from the fold that it forms with being [l’étant]. What is that? In Heidegger, it is fundamentally linked to the discovery of a constitutive finitude.

Therefore, it is here for the first time that one has the occasion to mark the importance in Foucault of these terms ‘fold’ and ‘unfold’, and also no doubt to sense that their roots are very different from the outset to what one finds in Heidegger. But it is here that, little by little, one will be led to proceed to a confrontation. Nevertheless, this is not our object for the moment. You see, I’ll restrict myself to this: the thought of the 19th century would be characterised by this: that, instead of human forces, the forces in man, unfolding themselves insofar as they enter into relation with forces of elevation to the infinite, there, on the contrary, the forces in man fold themselves, refold themselves, fall back on themselves, insofar as they enter into relation with the forces of finitude: life, labour, language. The triple root of finitude, the force of man surrounds like a helix, surrounds this triple root of finitude.

And that was what I insisted on last time, and on that point, it was still okay. I mean: it still worked. I insisted from that moment on the importance of taking into consideration that, for Foucault, the forces of finitude – life, labour, language – present themselves as exterior to man. Just as the force of elevation to the infinite was not a force in man, but was exterior to man, so the forces of finitude – life, language, labour – are exterior to man. It is imposed upon man from the outside under some formation. Labour is pain and time; it is a force imposed upon man. Language is an involuntary force, a force imposed on man. In the case of life, this goes without saying.

Therefore, I would say Foucault’s innovation is to be found here, at the level of this formation of the 19th century, for the idea that the revolution of the 19th century, the revolution in thought of the 19th century, lies in its having substituted for the infinite the idea of a constitutive finitude is fairly widespread and predates Foucault. It is not the infinite which is originary, it is finitude which is constitutive. I would say to you that this is the Kantian revolution. The human understanding is not a simple limitation of a divine understanding which would be originary; the human understanding, as finite, is constitutive. Thus, I can say that, according to a classical schema, the revolution of the 19th century is defined through the substitution of the originary infinity with a constitutive finitude.

Why does Foucault not hold to this schema and why is it that he renews it? Well, speaking for myself, I have the impression that the classical schema, ‘substitution of constitutive finitude for the originary infinite’ is all very interesting, but it leaves something vague: what was it that brought about this evolution at such a moment? Why is it that, all of a sudden, man comes to consciousness, not of his finitude – he is already conscious of that, even in the 17th century, it was even the source of his anguish and his unhappiness – but why is it that man all of a sudden comes to consciousness that his finitude is constitutive? That is, that it is not the limitation of a divine understanding, but that it is, on the contrary, the foundation of the world inhabited by man and of the knowledge put into action by man. I believe that the reason is … it is very simple. It is precisely what Foucault indicates. If you are following, this is why it was necessary at all costs to show clearly that the forces of finitude were not in man, but that man encounters them as forces come from the outside. It is because man at the end of the classical age comes up against the forces of finitude, that is, discovers life, labour, and language, it is because he comes up against these exterior forces, that he will come to consciousness of his own finitude with regard to himself, man.

Therefore, Foucault gives an explanation of what the classical schema leaves unexplained to the extent that he distinguishes two moments. The two moments, what are they again? These two moments are: first moment, the forces in man come up against the triple root of finitude, that is, against the exterior forces of finitude (life, labour, and language); second moment: man makes this finitude his own.

You see that it was very important for Foucault to distinguish two moments in the analysis of the formation of the 19th century, in order to explain why, at this point, the finitude of man becomes constitutive. This comes down to saying, in effect: when man, when the forces in man encounter as external forces, as forces come from outside, the forces of finitude, and no longer of the elevation to the infinite, then and then only, is the composite form man. It is no longer God, it is man. The forces in man come up against the forces of finitude: the composite corresponding to this new combination, to this new diagram, is the form ‘man’. I have the feeling that this is difficult. I do not know if it is difficult. This is the last time that we have to do with abstract things. After, it is … Therefore, you must gather yourselves for a last effort.

Appealing to a privileged example, I would like to verify this history of the unfold and the fold. The Birth of the Clinic, if I had to summarise it …, I certainly don’t want to save you from reading it, but I’ll just summarise. What would be a summary of Foucault’s book, The Birth of the Clinic? The distinction of two formations: the clinic, which corresponds to the classical age, and pathological anatomy, which corresponds to the 19th century. How to define the clinic? It is the constitution, at the level of diseases, which are treated as species, the constitution of a table, of a continuous table, which puts in place the series of signs and of symptoms. Unfolding [Dépliement], deployment of a table of signs and symptoms on the surface of the body. And the theme of the surface of the body is fundamental throughout the clinic. It is necessary that diseases declare themselves at the surface of the body, captured in a table which will mark the continuity of signs and symptoms. The clinic is fundamentally the unfold, the unfold of disease.

And now what happens in the 19th century? There is a discovery of tissues, the notion of tissue dominates, and will be the great notion on which pathological anatomy will found itself, replacing the clinic. And pathological anatomy gives or gives back a depth to the body, thanks to what? Thanks to the pleating of tissues; the tissue is what folds itself. At the limit, it is almost the birth of a topological space in medicine. The tissues fold themselves and the folds, the foldings of tissues give a depth back to the body, and to disease, a volume. And Foucault sees here two very different moments of the medical gaze. The clinical gaze on the surface which constitutes the table, and the gaze in depth of the pathological anatomist, which follows the folds of tissues in such a manner that it burrows into the depth of the body. As Foucault says, what do you want to do in an empirical autopsy? It is not that autopsy was not known, it was known, it existed for a very long time; but that it was devalorised, made secondary, follows immediately from the point of view of the clinic. With pathological anatomy, it recaptures all its force and will conquer new powers. To burrow into the depth of the body: but it was necessary that there were tissues capable of folding themselves and then, to be sure, of unfolding themselves. I note also that in The Birth of the Clinic most of the book is constituted on metaphors, not only metaphors, but on metaphors and the concepts of the fold and unfold. The thought of the unfold characterising the formation of the 17th century and the thought of the fold characterising the formation of the 19th century. Fine.

So then, there are two necessary moments in the 19th century formation. The encounter, the terrible encounter of man with the forces of finitude: first moment. Second moment: the manner in which man appropriates these forces of finitude and erects himself in constitutive finitude. I insist on this even when the traditional schema only says to us: constitutive finitude replaces the infinite. Foucault transforms the schema by distinguishing the two moments and I think that this transformation is very important; we will see the consequences. Is this second point clear? Okay.

Well, one glimpses a bit more when the forces in man coil themselves around the forces of finitude, when they fall back on the forces of finitude, life, language, etc., what happens? I mean: let us link together the troubles this introduces into the thought of the 17th century. Why is that the thought of the 17th century, in its specificity, cannot survive, cannot survive this test? Here we will see, even if it means that I depart from Foucault on certain points – which is to say that I’m making use of authors he does not cite, although I am quite sure, and it is obvious, that he knew them very well. But he does not say everything he knows …

Thus, I will sometimes attempt to allow authors to intervene… but just enough not to get in the way of your reading the text. I do not claim to give a summary. I will just say this: we will encounter three points. The 19th century will be the birth of biology, finite force of life, discovery of the finite force of life; of political economy, discovery of the finite force of labour; and of philology, discovery of the finite force of language. The explicit theme of Foucault is that in the 17th century, there could not have been biology, there could only have been a natural history; there could not have been philology, there was and could only have been a general grammar. At our current point, you are able to understand this. If I call biology, in effect, the science which founds itself on the finitude of life, I think that this is a correct definition; if I call political economy the science which found itself on the finitude of labour; nothing of that could appear in the 17th century, which for its part on the contrary developed, unfolded tables to the infinite: table of wealth, table of organic characters, etc. There was a place for natural history, there was no place for biology.

So let us try to mark out two moments in the birth of biology. It is around … The first moment is around the time of [Antoine de] Jussieu, the famous specialist of plants, and others. … Good. What happens? In a certain manner they still think in terms of the 17th century, namely the series of plants, the great continuous series of plants or even the great animal series where one will pass from species to another species, from genus to another genus, from class to another class, etc., by continuous transition. Table of living beings capable of being developed to the infinite. Immediate question: what is it that prevents them, in the 17th century, from being evolutionists, that is, from affirming that there is a history which makes us pass from one term of the series to the following term? You understand that one must even reverse the question: that question is not even posed. It is the series itself which prevents them from being evolutionists. There is no history of the living being, there is a natural history, there is a history of nature.

The history of nature consists in what? Well, it consists in the development of a series in which each element, each term of the series has its place, and each place has a term. The very idea that a term could pass into another is a idea that is strictly deprived of meaning from the point of view of the series. The development of living beings in continuous series excludes every history in which a living being evolves or a species is changed into another species. The series is the order of places of each species in continuity, in the continuity of nature; there is no place for a history, the serial point of view excludes history.

Now, around the time of Jussieu, what happens? More and more importance is attached … It is not that this was not known before, it was already known in [Carl] Linnaeus, the representative of classical natural history, but more and more importance was attached to two facts: that the organic characters, in a same species …, that the organic characters are all coordinated in a species, and that they are hierarchised, that is, that there is a character, for example in a species, which is more important than the others and which, in a certain fashion, determines the others. For example … and the point of view of functions is permitted to intervene from this moment. What is most important in plants is the function of reproduction. The function of reproduction will express itself in the organic character cotyledon, or in an absence of cotelydon, or in two cotyledons. Good.

One can put that in series, but this character, being more important than the others, will determine other characters which are correlative to it. There will be at the same time the correlation of characters, at the level of a species, and the primacy of a character over the others. Correlation and hierarchy. For the animal, certain authors think that what is essential, the dominant character, is the alimentary function. If the alimentary function is dominant, the teeth will be the principal character; but characters cannot be linked to each other indiscriminately. A type of teeth will bring with it a type of muscles, a type of stomach, a type of intestine. There is therefore simultaneously the coordination and subordination of characters, coordination and subordination of characters at the level of species.

Understand: to the extent that this point – which again was already known in the series of the 17th century, but … – to the extent that this point passes to the level of the primary plan [premier plan], the series is fractured. The series is fractured, that is, everything happens as if the terms of the series were – and here I weigh my words – attracted by a depth, and the series truly finds itself fractured there at the same time. You have no longer, or you tend to no longer have, a series of characters in continuity with each other and without evolution, each being having a place and each place having a fixed being, without history; there, on the contrary, the characters in a species, coordinating and hierarchising themselves, form a kind of weight which will fracture the series and draw every living being – but what does that signify, ‘each living being’? – into a depth which is no longer serial. If I were to make a sketch … but you see … I would put my series there, like that, and then at every moment where you highlight the coordination and the subordination of the characters, that makes a kind of disturbance there, which will, as it were, fracture the series, make the living being descend into depth, that is, will reveal what will appear as a new dimension.

As a result, in a sense, the idea of a continuity capable of being developed in series is fundamentally threatened in this first moment. To the series of surface is opposed (or it starts to be opposed) a wholly different approximation of the living being where the living being leaves the surface and sinks, sinks down, due to the weight of coordinated and hierarchised characters, and will escape the series. The series is… This is the word Foucault uses: “Jussieu fractures the series”. With an air of paradox that is very important, there will be all kinds of efforts to save the continuous series. Then, as a matter of fact, in the period of Jussieu … and Jussieu still imagines ramified series. The ramified series is … with discontinuities, with ramifications.

Thus, the series will infinitely complicate itself. Or else, then, a prodigious manner of attempting to save the series, which will be what? To inject history into it. You see, it is this that is very important in Foucault’s analysis because it concerns his method. His whole method of analysis and notably his method concerning statements: we will come back to that later, before too long. History was fundamentally repugnant to the series. Once again, each being had its fixed place, each place was for a determined being and there was no passage from one to the other. But when the series comes to know these fractures, bizarrely a means for trying to save the series will be to inject history into it, under what form? By discovering a force of life which will be defined how? As a tendency to a more and more differenciated [différenciée] composition, a tendency of life to compose more and more differenciated organisms, that is, organisms in which the characters present a maximum of correlations and subordinations.

An organizing force of life which will traverse the series in order to produce more and more complex organisms, that is, in coordinated and subordinated characters, and what is that? That is [Jean-Baptiste] Lamarck. But I’ll go very quickly, because it is not my concern at all to summarise the thought of Lamarck, what interests me is the manner in which Foucault situates Lamarck. Understand that he situates Lamarck and the first real appearance, finally the first incontestable appearance, of an evolutionism … he situates it in this way: Lamarck still thinks the living being under the form of development in series (in this sense he is a man who still belongs to the 17th century, to the classical age), and, in the face of the dangers, in the face of the threats that in his period put pressure on the idea of the series, he saves the series by making a historical force of life, by defining life as an organizing force that does not cease to produce more and more differenciated organisms, each in its place gathering a maximum of coordinated and subordinated characters. So yes, it is very curious: under a certain aspect – and one must say this of all thinkers – under a certain aspect they belong to an age, but under another aspect, they belong to another age. Lamarck belongs fully to natural history and, nevertheless, he introduces into natural history what is most repulsive to it, namely a historical process.

But why does he introduce this historical process? In order to save the series. So that here Foucault excels, although he does so constantly: he excels in his treatment of what results, and you already sense that it will form part of his theory of statements: for there is no question of establishing a lineage from Lamarck to [Charles] Darwin. They do not belong to the same formation. I say that this pertains to his conception of the statement, because statements that are apparently similar in fact belong to completely different families. We will see that as a matter of fact, Darwin is … this is another soil, as Foucault will say, another archaeological soil. Lamarckism can only be comprehended on the soil of the continuous series. Now this soil of the continuous series comes straight from the 17th century, and Lamarckism, as also in another way Jussieu, is simply an expression of the troubles that this continuous series undergoes in a first moment. Therefore, if I summarise the first moment at the level of biology, I will say: well, yes, the series tends to fracture itself to the benefit of a depth upon which the living being will refold itself, fall back on itself.

If I make a very simple schema: there is my continuous series [Deleuze writes on the board] which excludes history since each being of the series has been fixed and then, to the extent that the coordination and subordination of characters takes on more and more importance at the level of a term, at the level of a species, the series will be fractured, that is, there will be a reorganization in depth, the discovery of a depth, and life is no longer sought in the movement that traverses the continuous series, it is sought in depth in the movement through which the living being refolds itself, falls back into this depth, onto this depth. In other words, what the first moment introduces is what? It is the fundamental concept of organization, organization being the correlation and subordination of characters. That is the first moment.

Second moment: the great [Georges] Cuvier. The great Cuvier, who did what? At first sight, it does not seem like much. Substituting for ‘organization’, ‘plan [plan] of organization’. Plan of organization. The fundamental act of Cuvier, that is, the basic statement on which perhaps everything in Cuvier depends is the idea that there are plans of organization of life. What is a plan of organization? This is the second moment. One no longer discovers centers of organization which threaten the series, one discovers plans of organization which bring it about that there are no longer series, that every series is impossible. Cuvier discovers what he calls branchings [embranchements], great branchings of life. At first sight one might say: it’s fine, he is still stepping back to a higher generality. Which is to say, beyond the species, there are genera, and beyond genera, there are classes, etc.

Well, for his part, he goes still higher, he marks branchings. But no, not at all. This would be a misinterpretation, for the branching is a concept of a wholly other nature, it is a concept which is not at all on the same line as the others, since, on the contrary, it will render the classifications useless, it will put classification in question. What is the idea of branching? It is the idea that life is inseparable from plans of organization which exclude each other. Why is this important? It consists in saying that life is not only an organizing force, as Lamarck would say, a force of organization, it is a dispersive force.

The finitude of life is its dispersive force. Life proceeds according to a small number of plans of organization irreducible to each other and each exclusive of each other. Cuvier distinguishes four of them — it will undergo many variations, but four remains a sacred number — vertebrates, molluscs, articulata, zoophytes. The criteria of branchings … This will also vary throughout his work. Towards the end, he thinks that the fundamental character that defines the branchings is the nervous system, but the nervous system is susceptible precisely to four organizations, four plans, four plans of organization. In the case of vertebrates, this is: brain and an enclosed marrow in a bony envelope; another plan: nervous masses, scattered among the viscera, disseminated among the viscera, and reunited with each other via fibres. Masses reunited via fibres. This is a wholly different organization to vertebrate organization. Third plan: two ganglionary cords uniting with two principal ganglions above the oesophagus.

Fourth: the nervous mass is hardly discernible from the rest; tendency to indistinction. Good. Cuvier’s idea is: one does not pass from one plan to another. Understand, and this is very important for me: the living being will be defined by what? The manner in which it refolds itself according to this or that plan. This is what is astonishing in Cuvier, I think. An artist of folding. You will see what that sets going in the emergent biology. The living being is defined by the manner in which it folds itself according to this or that plan of organization. And that is where we find the finitude of life. There is only an unfolded life. In other words: end of the series! The branchings do not add themselves to series as more general concepts, the branchings render all putting into continuous series outmoded… [Interruption of the recording] [1:18:55]

Part 3

… you, embryo of a vertebrate, you do not fold yourself, you are not oriented in your embryogenesis in the same way as the embryo of an insect. And, between these different plans, there is an irreducible gulf, that is, each living being is sunk in the depth of its own plan and refolded onto its plan. You see that the series is completely broken there: this is the second moment. Then commences a period of biology, right at the birth of biology, of an extreme wealth, very beautiful, very beautiful, although looked at with an unkind eye, this was a biology full of polemics; these have not ceased to this day; they were polemics, however, which should still touch us and which it would be wrong to believe have been surpassed.

For you can see right away where I want to arrive. If I recount for you the histories of the fold, I have several ulterior motives: to give a basis to the comparison of Foucault with Heidegger, of course, but you will probably not be surprised if we arrive at the conclusion, for example, that what are the fundamental problems today concerning the genetic code and microbiology if not the way in which the chains of the genetic code fold and unfold? The figure of the unfold and the fold seems the constitutive figure of life. That does mean that, in the case of the genetic code, this should be at the same level, this will certainly be another biological formation, but it is ultimately just to say that here perhaps one touches on a problem it is worthwhile our dwelling on a little.

For, when I say: Cuvier had an enemy, whom he in turn made his enemy, this was [Etienne] Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, a very great biologist. So now Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire turns up and says: there is unity of composition. That is a statement signed by Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire: “there is unity of composition”; that is, that there is unity of composition for all living beings whatever they may be. Therefore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire opposes the unity of composition to the finite plurality of the plans of organization. There is a single plan [or plane, plan] of composition, whereas Cuvier affirmed the determinate plurality of four plans of organization. Then you will say to me, I imagine someone will say to himself at this point, well yes, that means that Cuvier is a fixist – he does not believe in evolution – which is true, and so that means that Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire believes in evolution.

No. Neither believes in evolution. We will see that evolution will be something else again. It is this point that must be explained. When Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire shows up and says “there is unity of the plan of composition”, one wants to say: he is returning to the continuous series. And, even there, no, he does not return to the continuous series. What should be said, in the style of Foucault, is that Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire is fully of the same epoch as Cuvier, he is under the same formation. Because what does he want to say? Geoffroy’s texts are quite extraordinary. He says: Cuvier distinguishes four plans of organization, but, by dint of folding, one could always pass from one plan to another.

Now that becomes interesting, and there is a very beautiful and comical page of Geoffroy – well, “very comical”, I hope that you will find it amusing — a page of Geoffroy where he says: for my part, I am going to show you how one passes from vertebrate to cephalopod — The cephalopod, this is not …, it is not an animal that is very … I will not even say what it is, the cephalopod, so that you will keep the secret; ‘cephalopod’, look it up in your petit Larousse, I do not want you to avoid any reading. In fact, the cephalopod, you understand, is no great thing – so, to pass from the vertebrate to the cephalopod, we tell ourselves: Cuvier is exaggerating. And here we have his formula. His formula is — I will only cite the start of the text –: “It suffices …” – there is a lot of humour in Geoffroy – “it suffices to lead the head back towards the feet and the pelvis towards the nape of the neck.” He makes foldings, he makes foldings; it is quite astonishing: starting from Cuvier’s folds, he will seek out the conditions under which one can fold a living being in order to obtain the axes and orientations of the other plan.[3]

At this point, the polemic starts up between Cuvier and … Cuvier is hopping mad. Why is he hopping mad? You understand that here one arrives at something that should be central for us, or which should be central for Foucault, namely that it is the same argument – the existence of pleatings – that allows Cuvier to say “you will not pass from one plan of organization to another, that is, each type of living being folds itself on its plan of organization”, and which allows Geoffroy to say “you will pass from one plan of organization to another if you make as many foldings as is necessary.” At the end of n foldings, you will have changed orientations, and you will have passed from the vertebrate to the cephalopod. It is the same thing that you can interpret in two senses. There are irreducible foldings which impose on me four plans of organization; or it is through folding that I will pass from a plan of organization to another. Obviously, the foldings are not the same. They cannot be the same, if not it would not be serious. And, in fact, Geoffroy – it is astonishing – makes the foldings upon anatomical elements. This is an anatomist. He makes foldings on anatomical elements. And notably on the bony elements. He makes foldings on the skeleton.

[Karl Ernst] Von Baer, for his part, immediately replies: none of that will work! Doesn’t it work? For my part, I don’t know. Why doesn’t it work? You can go and find Von Baer’s answer to him, in the name of embryology. He says: one can always fold solid elements in whatever direction, but there is no tissue which would support these foldings. There is not a single tissue which would support these foldings, so Geoffroy’s theory only works if one reduces the living being to its skeleton. If you wrap the skeleton around itself, if you join up what are called the girdles [ceintures] – it’s striking as language – if you join up the girdles, and then if you take account of the muscles and of the tissues, obviously, you cannot not make a folding, you will break everything, you will tear it apart … No, you do not break it, since it’s solid. You will tear apart the ligaments.

So, to speak like Foucault,[4] Geoffroy and Cuvier belong to the same archaeological soil, to the same family of statements, even though they say the opposite to each other. You can see why: because they have in common the falling back, and the not ceasing to fall back, of the living being upon …. or of folding it onto plans of organization or onto a plan of composition. In every way, the living being is refolded in depth instead of spreading itself out on the surface along a series. This is what is common to Cuvier and Geoffroy. And yet … there is more, what is shared is the refusal of every evolutionism. Because for Geoffroy one can pass from a mode of folding to another mode of folding, but these successive modes, these different modes of folding mark the degrees of development. They mark degrees of development. Now each type of animal has a degree of development which is assigned to it. It will not transcend its degree of development, which therefore condemns it to such a plan of organization. What Cuvier would call ‘plan of organization’ is for Geoffroy the degrees of development of a single and same plane of composition. And at this degree, each takes part in the other, it is very beautiful.

So, both refuse all evolution. Moreover, to the extent that on Cuvier’s side, with von Baer, a fantastic science, embryology, was founded, on Geoffroy’s side, Geoffroy himself founds a fantastic science which will form a part of biology, namely, teratology or the science of monsters. For, if every plan of organization is only a degree of development for a single and same plan of composition, from Geoffroy’s perspective, it can still happen that a living being should be stopped in its development by external circumstances, by an accident or by a disease. And what is a monster? Geoffroy will propose his great definition of the monster: it is either a fixation or a retardation of development. A fixation or a retardation of development, that is: it has not attained its development; prevented by an external cause, it remained fixed.

For example, there is a very interesting monstrosity about which Geoffroy says: ah yes, it has remained at the crustacean stage, it has not transcended the degree of development of the crustacean. The crustacean is … Geoffroy is full of statements, of formulas which are quite spiritual, er, he … To be crustacean, says Geoffroy, broadly speaking, is to have one’s skin on one’s bones. There is a monstrosity where the skin is on the bones; in effect, there is a very light integument on the carapace. To have one’s skin on the bones. And the flesh is on the inside. That is a crustacean. So to have development halted at the crustacean stage, that means I have my skin on the bones. It is … well, it is a disease, it is a known monstrosity. … Or in embryology, for example, one does not overlook the fact that the hands develop themselves before the arms. Assume that an embryo develops itself and develops normal hands, but then an accident comes at the moment …or a virus arrives at the moment it is in the process of fabricating its arms. It will have perfectly normal hands and atrophied arms. This is a known monstrosity.

Well, this is the very illustration of Geoffroy’s definition: the monster is a retardation of development or a fixation of development. In this case the embryo has its development fixed at the stage ‘formation of hands’. It can no longer form an arm, a normal arm. Assuming that the formation of the arm was posterior to that of the hand. Here I make an indication, I open an unnecessary parenthesis, but for the sake of epistemology: when a famous discipline will invent or will say that it invents the notion of fixation and regression, and will explain the neuroses through the phenomena of arrest and regression, one must render to each what belongs to him, which is to say: what is already fully original is the application to the domain of the neuroses of concepts that are teratological in type, dating back to Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, for instance, regression; for Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, arrest of development, the fixation of development are the two principal formations of monsters. But it is well known that neurotics are monsters. [Laughter]

So, you see, it is around this theme of the folding that I can say: of course, they understand the foldings, the folds, the refoldings of finitude, that is finitude, it is the fold, it is what folds itself, it is what refolds itself, it is what refolds me. Whereas raising to the infinite is what unfolds itself, it is what deploys; it is not more difficult than that. The thought of the 17th century is a thought of deployment, why? Because it reacts against the Renaissance and against the Middle Ages. Then must one say that it was a thought of the fold, the Renaissance and the Middle Ages …? It was something else again.

But the 17th century affirms the unfold, as the law of clear and distinct thought, as the law of order. If you want to grasp order, unfold things. That is the method …. It would even be necessary … one could go in both directions … Take the Cartesian method, take a method dear to the 17th century: every time you will see the formation of series, the formation of chains, the search for contiguities, all that, a thought of development, of the unfold. With 19th century thought comes the obscurity of the fold. It is necessary to fold things. At that moment, you have the discovery of finitude. To fold the living being on the plane of composition or to fold on the plan of organization, all that runs parallel. But last point: Darwin. What role does Darwin play here?

Well, you know, with Darwin, what is involved is precisely not the series. When Darwin will affirm and inject history, that is, evolution, into biology, what does he do exactly? What does he do exactly? He brings something new. There is now a trinity, he is simultaneously against Cuvier and against Geoffroy. But how are Darwin, Cuvier and Geoffroy a trinity, at the horizon of our biology? Why is it that … even though Lamarck… You see the big difference: even though Lamarck introduced history into the series, in order to finally save the idea of an animal series, this means he was still at the first moment of biology. This was not the case for Darwin. For Darwin, that was not the problem. That was not his problem. I mean: Darwin is happy to accept the same terms as Cuvier. What were Cuvier’s terms? The series proceeds via small differences, but there are large differences between plans of organization. In other words, there are insurmountable differences which break up every possible series.

You understand? Tired? But I will not stop there, because if I stop, that will be like the other time. So, when you’ve had enough, you’ll just stop listening … or … What time is it?

Lucien Gouty: 11 o’clock, coming up to ten past.

Deleuze: Then I’ll go on but take a short pause … but … ah. No, no! I’ll finish Darwin first, because if not, we won’t be able to move on. You understand Darwin … but nevertheless for those who have read a little Darwin, what I am saying will have a grotesque air. What I am saying is that for Darwin, the little differences are all the same to him, he never thought about re-establishing the series, the series that proceeds via little differences. What I am saying has a stupid air about it, since it is well known that Darwin, on the contrary, perpetually invokes the little differences of a child in relation to its parents. To be sure, he needs to do that. But why? Is it in order to put into series that he invokes the little differences? Not at all. It is in order to be able to reply to the question: why are the large, apparently insurmountable differences imported into life? Why does life, which ceaselessly produces little differences, proceed nevertheless through the action of large differences? Now that, you understand, is a problem that could not be posed before Cuvier or before Von Baer.

And what is Darwin’s answer, then, which is such an innovation? You will see, it is that it really engages with things; I will recount it, let us see. Darwin’s answer comes in two stages, it seems to me. It consists in saying: if you take, not a environment, not a general environment, for example water, but if you take a determinate territory, a determinate region in an environment, under what conditions can a maximum of living beings survive? This is the new question of Darwin. This is the Darwinian question: assuming a territory, under what conditions can a maximum of living beings survive? That is a question has no equivalent either in Geoffroy nor in Cuvier. But the answer will join Cuvier and Geoffroy up with each other again. It consists in saying: they will have all the more chance of surviving the more they diverge, the more their characters diverge. Assume a determinate region and then two closely neighbouring species which live in this region; ‘closely neighbouring’ here means that their food is identical or similar. There is one that will get the better of the other and which will liquidate the other. You see that the whole theme of natural selection is given in profile there. They could not coexist. Assume the contrary, that the two species which live on this territory are very different, then they have chances of coexisting, of surviving. They do not appeal to the same nourishment.

Good: it is by dint of divergences that a maximum of living beings can live on a determinate territory. In other words, life will define itself as a tendency to produce large differences through an accumulation of little differences. This is the condition of survival: the tendency to produce large differences. That is, life is no longer considered as a force of dispersion, but as a force of divergence.

Henceforth, Darwin will tell us that it is not surprising that life should be traversed by these kinds of break between plans of organization. What is left over – second aspect of the Darwinian thesis – is this: how can there be history, transformation? Well then, precisely, the creation of large divergences. But how is it that they can be created, these divergences? Since every living being seems already to suppose distinct plans, distinct plans of organization. Darwin’s answer will be that here you cannot infer from the evolution of the embryo to the evolution of the species. You cannot apply the laws of embryology, why? For a very simple reason: because, in embryology, the forms are already given. You are always the embryo of a form; the forms here are already fixed. For example, an embryo of a wolf is an embryo of a wolf, it will produce a wolf. Even with little differences, it is sad, but … Whereas at the level of the evolution of species, the forms are not fixed. You only have forces in relations. The forms are not fixed, they are themselves fluid. There is no species which would be wolf and then a species, etc. You see, he overturns everything. If species are the product of an evolution operating through accentuated divergence, you cannot already give yourself species, that is, forms, beforehand.

So, what is Darwin’s true revolution? It is not evolutionism at all, it is to have thought life in terms of population and not of form. Population on a given territory. Any population whatever on a given territory. You cannot already give yourself forms. And evolution, what is that? It is precisely that this population will only be able to survive to the extent that it splits and produces divergent forms which allow its members to survive on the territory. In other words, Darwin’s evolutionism has nothing to do with Lamarck’s evolutionism. For Lamarck’s evolutionism is typically a serial evolutionism, an evolution that injects history into the series, whereas Darwin’s evolutionism is typically an evolutionism which confirms the collapse of series to the advantage of the refolding of the living being onto a force of life which will be a force of divergence and of accentuating divergence. Now all of this, at whatever level, whether it be Cuvier, whether it be Darwin, whether it be Geoffroy, is done at what price? This refolding of the living being onto the finitude of life is always done to the profit of putting death into life. In this shadow of death, depth is thus created.

Theory of catastrophes in Cuvier, theory of selection in Darwin, theory of monstrosities and of arrests of development in Geoffroy. The finitude of life will put life into a fundamental relation with death that the 17th century ignored. In other words, to death … The 17th century, I believe, could only think death in the manner of a wisdom [d’une manière sage]. What does wisdom signify? It is ancient wisdom that says to us: what are you complaining about? In so far as you are not dead, you have nothing to complain about; and when you are dead, you can no longer complain; therefore, death is an instant. But what I am summing up as wisdom or moralism – it is the moralism of Epicurus: it is impossible to think death, which is an instantaneous event – that also held for all the medicine of the period; it had its epistemological version, it had its scientific version: death as decisive and indivisible instant.

And I think I already said this to you when we were talking about something else: when one finds the famous formula ‘death is what transforms life into a destiny’ in [André] Malraux, and then again in [Jean-Paul] Sartre, far from being a modern formula – this removes nothing of its beauty – it is fully the expression of classical thought, it is death as instant, instant which, precisely, brings about a kind of transvaluation of life: it transforms life into destiny.

But the thought of 19th century, and perhaps our own, has a completely different conception of death. Just as the living being folds itself onto finitude of life, life in a certain manner refolds itself onto death. What does that mean? The great book on death, in my opinion, remains a book that Foucault loved and admired immensely: this is [Xavier] Bichat’s book, a famous doctor, Physiological Researches upon Life and Death [Recherches physiologiques sur la vie et la mort]. And Bichat proposed a celebrated definition of life which indeed sometimes causes laughter, but only in imbeciles. It is: life is the set of functions which resist death.[5]

Now the imbeciles – and they were numerous, not so much now, but there were numerous imbeciles in Bichat’s day – they say: that’s a big vicious circle. In effect, to define life as the set of functions which resist death would suppose, they say, that one could define death independently of life. Okay, but the objection is idiotic, because the objection would only be valid if Bichat maintained the classical conception of death. Death presupposes life, yes, therefore one cannot arrive at Bichat’s definition if death is conceived as a decisive instant which terminates life.

But Bichat, for his part, in his book, proposes to us what I believe is the first great modern conception of death. He proposes it on two points. First point: death is not a decisive instant which marks the end of life, death is coextensive with life. Second point, which accounts for the first, which clarifies the first: the living being is inseparable from the partial deaths which traverse it. And what one calls death, far from being a decisive instant is always the global effect of several partial deaths. There are three partial deaths: the death of the brain, the death of the lungs, the death of the heart. And even if life does not cease, the living being, at least the animal, is rarely alive: not only is there sleep, but there are partial sleeps. The living being does not cease being traversed by partial sleeps which are veritable deaths. Partial sleep in Bichat comes to echo partial death. At one and the same time, death is coextensive with life and there is a plurality of deaths.

Therefore, in neither of these two senses can death be considered as decisive and indivisible instant. Now it is Cuvier’s achievement, I say to you … Biologically, the living being can only be pushed back onto the force of life, onto the finite force of life, to the extent that death is inscribed all the more profoundly in the living being itself. And this is something that will greatly disturb very Foucault, who always had a kind of relation with death… And I think you will find, in The Birth of the Clinic, 5 or 6 pages on Bichat and on the theory of death in Bichat. If you read it, you will see for yourselves. For myself, I have the feeling that, of course, this is an interesting epistemological analysis of the thought of Bichat, but there is something more, there is something more which … where Foucault expresses his … his own relation, his own relation with death and a kind of adherence to what … to the manner in which Bichat presented things.

So, you see that I’ve done a summary there of one of the three [forces of finitude]; it ended up taking a while, but to me it appears necessary. At the level of the formation of biology, we have clearly seen our two times. If I try to summarise the two times, I would say: first time – the two times are grouped together in the formula ‘when the forces in man encounter the forces of finitude’ – first time: one encounters the organizing force of life, one encounters an organizing force of life which is marked by finitude and which compromises the series of the 17th century. Second time: the organizing force refolds itself in depth, at the same time that living beings refold themselves on their plan of organization. These are the two stages. Now what Foucault will show in The Order of Things is that aside from biology, the same thing is produced at the level of political economy and its birth in the 19th century and at the level of philology and its birth in the 19th century… [Interruption of the recording]

… The hypothesis, the minor hypothesis, not very interesting, that I will propose to you, is this. Again, when we arrive at the issue of a confrontation of Foucault with Heidegger, and I am obliged to shed some light on what Heidegger calls the fold, and to state that this is a very profound theme in Foucault, that of the fold and of the unfold … I think one can rather quickly arrive at the conclusion that the origin of this notion in Foucault does not lie in Heidegger; and this seems to me to go without saying, in the light of the very different use he makes of it. So, it is true that there has been in this regard an encounter of Foucault with Heidegger, but in Foucault, the notion of fold and unfold has a completely different origin. And I think that the originating principle lies in this history we are in the process of seeing: the fold and unfold are like two functions of thought, the one consisting in developing to the infinite according to the mode of classical thought, the other consisting in falling back onto finitude in accordance with a thought which is elaborated with the 19th century. So that is a first point, which seems to me important. In this regard it remains for us to see, and perhaps you have already, the equivalent of what we just saw for biology in the 19th century formation in the fields of political economy and philology or linguistics. So, here I’m going to go very quickly, in order to give you just the landmarks.

What happens in political economy? Well, once again, in the 17th century, there is no political economy, there is an analysis of wealth and there is a table of wealth capable of being developed to the infinite, at the same time as needs. Of course, this is an infinite which is only indefinite, but again, we saw that the indefinite was an order of the infinite for the … It was no doubt the lowest order of infinity, but it was an infinity, such is the incapability of the 17th century to think outside the orders of infinite. ‘Incapable’ is a compliment, it is not a critique. Now, in an analysis of wealth, of course, labour has its place, and the notion of labour already exists and already serves its purpose. But labour, such that it is employed in the 17th century, indissolubly links together two things. It links what one could call the labour of production [travail production] and the labour commodity.

And the two are connected, the two are not separate: hence a great equivocation in the notion of labour in the 17th century. Labour is a commodity, and indeed it is paid for. The payment of labour is called the wage. To the extent that labour receives a wage, it is a commodity. But considered as production, it is something else, it is a unit of measure, it is a unit of measure of the product. Fine. That comes down to saying, in the notion of labour in this state, that labour is essentially qualified. This will be a labour … of the manufacturing kind or even a commercial labour, or an agricultural labour. Labour is this, this, and this. And finally, the function of labour is to be a relative unit of measure, a relative unit of measure that leads back to what? That leads exchange back to need. I’m going very quickly, these are just the milestones.

Fine: where is the fracture? From the moment there is a table of wealth, a series of wealth where labour, such as it is conceived, assures the circulation of wealth in the table. The great fracture is Adam Smith. This is the first moment of the 19th century formation, and there again one will rediscover the two moments. And what does Adam Smith do? It could be that he does something very important, that is, he dissociates the two aspects of labour, the waged aspect and the unit of measure aspect. So that perhaps Adam Smith’s most important texts consist in saying to us: regardless of whether labour should be paid well or poorly, the unit of labour remains identical. That implies what? It implies what Marx calls “Adam Smith’s stroke of genius”, that is, to have isolated labour as the subjective essence of wealth, or of having isolated abstract labour as being no longer qualified as this or that.

In celebrated texts, Marx tells us: political economy starts with Adam Smith, why? Because Adam Smith isolates abstract labour and therefore isolates labour power tout court, labour power tout court [Deleuze repeats]. And by virtue of the same, adds Engels in a very interesting text, Adam Smith is the Luther of political economy. Why? Because labour power tout court or … the subjective essence of wealth, is more or less the same operation as is made by Luther at the level of religion. At the level of religion, Luther substituted – in short to go quickly – Luther substituted for exterior religion an interior religiosity which, in a certain way, is any religiosity whatever, the subjective essence of religion. Likewise. the rupture of Adam Smith with the 17th century, according to Marx, is: from objective wealth he separated out the subjective essence of wealth under the form of abstract labour, of labour tout court, of labour power tout court. In other words, with Adam Smith, thanks to the dissociation of the two aspects of labour, waged labour and labour of production, commodity labour and labour of production, labour becomes the unit of measure … [Interruption of the recording] [2:05:43]

Part 4

… Here again, it is a kind of operation of folding. There are pages of Marx where he explains it very well, he calls it an enchantment [féérie], the enchantment according to which capital appropriates labour, the phantasmagoria, the kinds of refolding of labour onto capital. And at this point, what is the difference, the fundamental difference [David] Ricardo-Marx? Here again, just like Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and Cuvier, just like Darwin and Cuvier belong to the same archaeological soil, Marx and Ricardo belong to the same archaeological soil.