May 6, 1986

I am saying: the rules of power in a social formation are the obligatory rules – you must obey. The rules of knowledge, the code of virtue is, in another way, also obligatory, another type of obligation. But governing oneself, as a regulatory principle and no longer a constituent principle… governing oneself is something else entirely. I would say: it’s an optional rule [règle facultative]. You’re a free man. If you don’t want to govern yourself and if you want to govern others, at that moment you become a tyrant.

Seminar Introduction

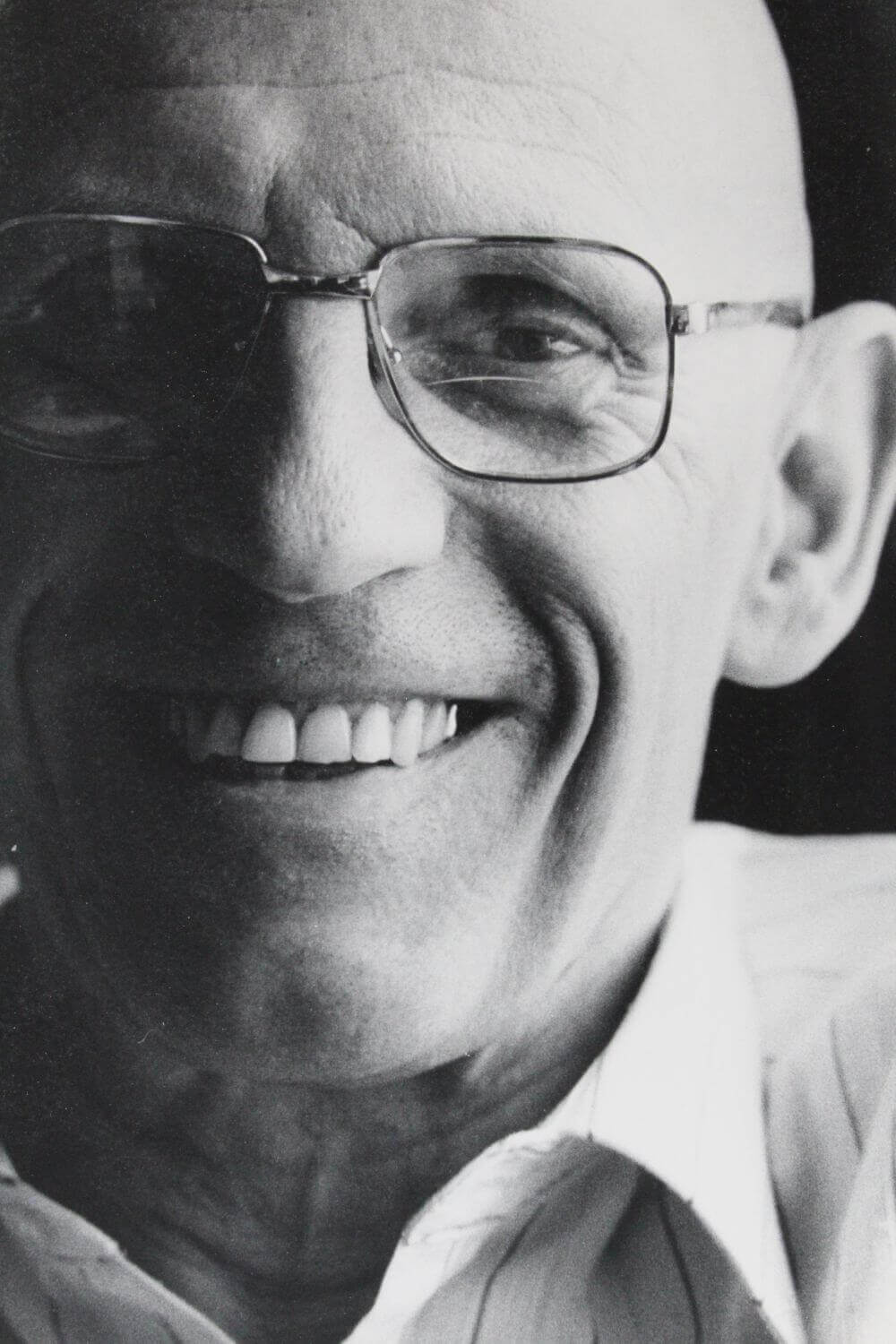

After Michel Foucault’s death from AIDS on June 25, 1984, Deleuze decided to devote an entire year of his seminar to a study of Foucault’s writings. Deleuze analyses in detail what he took to be the three “axes” of Foucault’s thought: knowledge, power, and subjectivation. Parts of the seminar contributed to the publication of Deleuze’s book Foucault (Paris: Minuit, 1986), which subsequently appeared in an English translation by Seán Hand (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

Still situated within the “subjectification” chapter in the Foucault book, this session moves from discussion of the Greeks toward complementary perspectives in Nietzsche, closing on subjectification and the fold (cf. The Use of Pleasure). Starting not just regarding Foucault’s turn to the Greeks but also with the historical response to this question of why philosophy and Greece, Deleuze links this question to reflections within German philosophy (notably, Hegel and Heidegger). Here Deleuze emphasizes that for the Greeks, there were new relations of forces between free men, and that only free men could govern free men, but only the one capable of self-governing was able to rise to governing others (enkrateia, or power of the self). Deleuze maintains that for Foucault, this self-governing is the third axis of thought, force folding itself onto itself and affecting itself as a subjectification or doubling of force. Finally, distinct from the axis of knowledge or of power, the third axis is the bending of the relationship of forces or subjectification. Deleuze insists that subjectification as the production of a subjectivity takes place with four foldings that we live in, make and remake: first, the fold surrounding a determinable material part of ourselves; second, the fold as the rule according to which a fold is made; third, the fold concerning the relationship of myself with the truth (and vice versa); fourth, Finally, the fold as the interiority of waiting (attente). Deleuze insists that an urgent question of sexuality’s role in all this finds an immediate answer, that it is in sexuality that the relationship to the self is actualized. Providing details on this actualization in three forms of relationship (simple, composite, and cleft or doubled), Deleuze also traces the conundrum of the optional rules of self-governance being appropriated into constraining, constitutive rules of knowledge and power, concluding that through new folds taking shape, new forms of resistance can emerge. Hence a final question for the next session, what mode of subjectification can we hope for today and now?

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Foucault, 1985-1986

Part III: Subjectification

Lecture 22, 06 May 1986

Transcribed by Annabelle Dufourcq; time stamp and additional revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Translated by Melissa McMahon; additional revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Part 1

This is where we were, you remember… with a question specific to Foucault: what does this apparent return to the Greeks represented by the last books of Foucault mean? We went via a more general question first, which was: well yes, how does Foucault fit into the tradition or traditions that ask the question “Why the Greeks?”, which is to say, “Why was philosophy born in Greece, and is its relationship with Greece one that can be articulated?” Articulated how? Is all this… Is this a well formulated question? I have no idea, I have no idea. Should it be formulated in that way? Is it appropriate to say that, yes, the Greeks had a foundational role in relation to philosophy? I don’t know, myself. But we take it as it is. We take it as it is, because it is where our subject leads us and because it is Foucault’s thought we are concerned with.

Now what I wanted to say last time, very quickly, was that the question seemed to me to have arisen with German Romanticism, but that since the nineteenth century this question, “why philosophy and the Greeks?”, has received three types of response which are quite different and yet linked, complementary, much more complementary than contradictory. One concerns… one is philosophical and concerns the revelation of being. I am putting it in very general terms, very vague terms and very vague as a matter of necessity because it covers very different authors. I’m saying: it seems to me that in German philosophy, from Hegel to Heidegger, the response we are given in relation to this problem is: yes, being revealed itself in Greece. What bothers me is the slightly… well, it’s not, it’s not… it’s not a drawback, but the slightly Christian side of this… of such a response. I mean: they say “Being revealed itself in Greece” a bit like… where in other places people say that God became man in such or such a place. The unity of the singularity and the universal… That’s why I say: perhaps, in the end, the problem is not well formulated. But, well, once again, that’s not our business. Yes, being revealed itself in Greece, all right. We saw this, very quickly.

And what does that amount to saying? Well, if I go back to Hegel’s formulation, very quickly: in what form does being reveal itself in Greece? Well, it reveals itself immediately. The immediate revelation of being happens in Greece. In what form? Being appears there as, properly speaking, the universal of objects. And that’s the beginning of a long story, which is history itself, which is to say the history of philosophy. Because next comes a mediation or a – the word here is important for me – a subjectification, already. The second moment is a subjectification of being or, if you prefer, already, if we highlight the notions that are important for us, being folds back onto [se replie sur] the subject, who represents both the object to itself and itself to itself. This is the second moment, no longer the immediate, but the moment of reflection, which no longer bears the mark of the Greeks, but of Descartes: I think therefore I am. Being folds back onto the subject who represents itself to itself and the object to itself. And then, in a third moment, which is the moment of the absolute – I don’t need to tell you how much I am simplifying things, but the three moments are definitely, are very clearly differentiated by Hegel in his course on the history of philosophy – this time it is the movement of the subjectivity of the subject, the movement of subjectivity which deploys itself in being, which is to say that, in thinking itself, thinks being. And this is the properly Hegelian moment with which Hegel thinks he has completed philosophy.

But let’s be clear, I am saying – but I don’t have time here and it really wouldn’t be my area – I understand that Heidegger is very different to Hegel. I am saying that the Heideggerian conception of the relationship of philosophy with the Greeks nevertheless grew out of that particular soil, namely Greece as the place of the revelation of being. The great difference between Heidegger and Hegel is the way the two authors conceive the revelation of being. But the fact that there is a revelation of being in Greece and the start of a movement of subjectification as the fold of being, that is a theme with Heidegger’s name on it just as much as, in a certain way, it has Hegel’s name already on it. So, this first philosophical current in relation to the question of the relationship of philosophy with Greece could be expressed as: yes, the revelation of being takes place in Greece, and that’s what we call philosophy.

And then there is a second response, a second type of response, which we won’t call a philosophical response anymore, which is much more of a historical response. And at the same time, I would like you to have a sense of how unfair it is… there is something unfair in the extent to which the historians, I was saying, neglect the philosophical response, as though it had nothing to offer them, whereas in my opinion their research would not have existed without the mode of questioning that was in the first place philosophical. Because what do the historians tell us? It is no longer a matter of saying “Yes, being reveals itself in Greece,” that is unintelligible to them, that is… that is pure and simple metaphysics. On the other hand, on the positive side, they say that there is an organization of the cosmological and social space in Greece that implies a new mode of thought, which the Greeks will call philosophy. So, the response is no longer: being reveals itself in Greece, but: a new cosmic and social space appears or is organized in Greece.

What does that mean? I’ll go very quickly and say that it is a bit like the Hegel-Heidegger situation just now – I myself believe that the first great Greek historians in Germany in the nineteenth century emphasized this aspect of the new space. You can sense it straight away: it is the space of the city. And we can follow the traces from the nineteenth-century history of antiquity to the school… to the current French school I was referring to, three particularly important names in this orientation, namely [Jean-Pierre] Vernant, [Marcel] Détienne and [Pierre] Vidal-Naquet, who analyzed this new cosmic and social space which made a new mode of thought possible, called philosophy.

But what was there before? Before, there was a thought… I am summarizing, I am very quickly summarizing, those of you who are interested should go and look at the texts. Let’s say it was a “magico-religious” thought, as it is often called. A magico-religious thought which corresponded to what? Which corresponded to, let’s say, the great imperial formations. Even in Greece, Mycenae, imperial Mycenae. These great imperial formations, which we have quite substantial information about, you’ll see all of that anyway. So, for example Vernant asks: how is this type of thought – let’s call it pre-philosophical thought – defined? This type of magico-religious thought. Others would say “poetic,” the thought expressed in poetry. It is expressed by the affirmation of a gap. The affirmation of a gap between what and what? A gap between two meanings of the word “first.” What is first from the point of view of the beginning, or the temporal point of view, and what is first from the point of view of sovereignty, from the point of view of power.

This means something quite simple. You see: what is first from the temporal point of view is chaos. In the beginning, there is chaos. And what is first from the point of view of sovereignty is the sovereign god. It is Zeus. And what is magico-religious thought? It deals with everything that is supposed to happen in the gap. It took time to tame chaos – why? Poetic language, or mantic language, mantic in the sense of… or divinatory, if you prefer, tells of all of the battles between the generations of gods, between the two extremes of chaos and the sovereign god, everything that happened, the Titans, the battle of the Titans, how the Titans were vanquished, etcetera, etcetera. How the generations of gods succeeded one another until the greatest god asserted himself and imposed order on chaos at the same time as he triumphed over the other gods. So much so that the world, in the poetic or pre-philosophical language, is presented as a hierarchy of forces [puissances] struggling with each other, which fills in the distance between chaos and the sovereign order.

This is to say, this is very important to me, because I’ll just say, when there is this idea all over the place, when it comes up, an idea like “oh yes… archaic thought is the thought of the eternal return,” it’s completely false, the idea that things come back, etc., it is so false. Once again, think about what you may already know yourselves, but archaic thought, to my knowledge, never invoked any kind of eternal return, it invoked the exact opposite, which is to say this succession of divine generations to the point where a sovereign god assumes power, which is to say that archaic thought has always invoked the succession of generations. And one of the last Greek examples of this kind of thought is Hesiod. And what are its aims? It has two aims: to sing the praises of sovereignty and how sovereignty came about, and, in light of that, to recall the great feats of the warriors. And these are the two fundamental functions of archaic poetry.

But what happens in Greece, what does “philosophy is born” mean? First of all it means – and this is how you recognize a philosopher, the first Greek philosopher, except of course several already arrived at the same time – this is how you recognize a Greek philosopher: it is someone who tells you, no, the universe has an immanent law of organization. What is first in the order of time and first in the order of sovereignty is in a certain way the same thing and at the same time, even if it takes time to emerge – it’s possible, all kinds of middle grounds are possible of course, pre-philosophical thought will continue in philosophical thought. It’s possible to conceive of an immanent law of organization of the universe that takes time to emerge. It is still the case that it’s an immanent law of organization of the universe that is affirmed and not a chaos. Or, if you prefer, the earth in a position where it is balanced in the center of an already homogeneous space. The earth balanced in the center of a homogeneous space. That is the signature of philosophy – in what sense? Because it no longer needs a sovereign god to hold it up. The question “why doesn’t the earth fall?” no longer exists. That was the magico-religious question: why doesn’t the earth fall? If it is balanced in the center of an already homogeneous space, it has no reason to fall. In other words, this is a way of saying that there is an immanent law of organization. You see, what was affirmed as a gap, the gap has been completely [slapping sound] flattened, folded [slapping sound]. That’s a certain manner of folding as well, to fold, fold down [slapping sound]. I fold the sovereign law onto [slapping sound] the earth itself. And at that moment philosophical language begins.

But where did such a conception of the cosmos come from? It’s that at the same time there was an evolution or even a mutation of the social space. The social space stops being pyramid-like, with the point of sovereignty, the summit of sovereignty, and the tiers representing the generations of gods who succeeded each other. There was a kind of flattening or folding inwards in this case as well. What was it? It was a new social space defined by, to use the Greek word, isonomia. And what was the great isonomia of the Greeks? It was that they posited a homogeneous space, all parts of which were, in a certain way, symmetrical in relation to a center. The center of a circle replaced the very different image of the summit of a pyramid. The summit of a pyramid whose tiers represented the successive generations; now it was a matter, on the contrary, of the center of a circle, in which all of the parts have become reversible and symmetrical in relation to the center.

And what was that, once again? It was, firstly, the great constitution of Cleisthenes, which – this is common knowledge and what I’m saying, once again, is extremely basic, I have to… I’m obliged to go quickly, all I can say is that it’s not false… I’m ashamed, this is Dictionnaire Larousse level, really – this is as if it has always been said, about replacing the gentilis-based distribution,[1] which is to say a distribution based on tribes or peoples [gentes], who were defined according to how long they had been in existence, the pyramid image, the pyramid image of the generations… replaced this so-called gentilis-based distribution with a territorial distribution – the different territorial parts, the different parts of the territory, being symmetrical in relation to a center. What is this center? The famous agora. The famous agora of the Greek city. Which is to say the common meeting place. The idea of the common meeting place which is substituted for the summit of the pyramid.

And no doubt people will say that this is Athenian democracy. And we will recall that Plato, the philosopher par excellence, was violently hostile to this democracy. But everyone knows at the same time that this is not an objection, because what is the true philosophical problem in Plato? It is not at all a matter of going back to magico-religious language, to pre-philosophical language or pre-philosophical thought, but about asking under what conditions isonomia – the need for which he perfectly recognizes, because isonomia becomes the very model of justice, of the rule, the rule of symmetry of isonomia, it can be translated as the rule of symmetry, equality or proportion – the Platonic question is how can isonomia – which is to say, Cleisthenes’ ideal – how can it be effectively realized, once we say that it is not and cannot be realized in Athenian democracy?

So, why can’t it be? Well, there, it doesn’t really matter… How does Plato… I’ll just say: Plato’s response is that Cleisthenes’ ideal can only be realized, can only be put into effect, if we reintroduce a strict hierarchy into the city, a hierarchy of the following type: where the leaders, the rulers of the city, have no other profession than to rule, because it is the distinction between professions, the distinction between occupations, that prevents Athenian democracy from realizing the ideal of isonomia. So, a hierarchy must be restored, but not at all in order to go back to magico-religious thought, just to… to arrange things so that the rulers are removed from any professional activity apart from politics itself, which is to say so they are in relationships of isonomia among themselves, in relation to each other. That doesn’t mean there aren’t certain elements in Plato that draw on and reactivate a type of magico-religious thought, hence Plato’s use of myth, in particular, but in a completely different context and with a completely different aim.

But if we look, in fact… this is to say that Plato completely holds on to the Cleisthenian conception of space, in fact, he just thinks that Athenian democracy is completely inadequate for realizing this space in the city, this isonomic space. And more than that: that to do this it is necessary to replace the symmetry of parts with equalities of proportion, in other words relationships of analogy. So, the differences with… But this is to indicate that he belongs, that Plato, even when he seems to completely distance himself or move away from this problem he still, here as well, wholly belongs to the sphere of this problem. And it is very interesting if you look into it, one of the origins – we can see then that there is a cosmic origin of this new organization or conception of space, a civic origin of this new organization, and similarly I would say that there is an origin that Détienne has analyzed very well in his book Les Maîtres de vérité, analyzed very, very well, which is the warriors themselves.[2] It’s that the warriors, for their part, don’t just wage war. What do they do? Well, perhaps this space, this new Greek space was born among the warriors. The warriors always had a special status, and what did this special status consist in? A type of language that was unique to them, a manner of… [Interruption of the recording] [28:17]

Part 2

… comes to the center, the one who has something to say to his warrior equals. And when he has said what he has to say, he goes back to his place and another one who is his equal, equal in rank, another chief, comes and speaks in turn. The word or booty is thus placed in the center. And all of the parts are symmetrical in relation to this center, in effect, all of the warrior chiefs are peers, equals. A new type of language is born there, a new type of thought, a social space, a circular space defined by the symmetry of the parts in the relationship to a center. And should it be any surprise that this space develops and becomes a civic space? It becomes a civic space at the same time that the famous so-called “hoplite” reform takes place, which makes a soldier of the citizen or a citizen of the soldier. So, you see, Cleisthenes’ reform, the hoplite reform, etcetera, the organization of a new space takes place through datable and historically determinable reforms.

Georges Comtesse: May I offer a comment?

Deleuze: Yes?

Comtesse: I’d like to point out that… [Inaudible comments at the start, concerning details of the Greek civic organization] … citizens who were around a circle, at equal distance from a center, it was at the center that [inaudible word] by someone called [inaudible term], and the difference of this [inaudible term] with the other formulations of [inaudible word], is that for it equal law for all in which citizens around a circle, at equal distance from the center, and that the disposition of the figure of democracy, it’s that the center… in the center, there wasn’t anything, that is, there was neither booty which varied [inaudible words], nor the chôra, to speak [inaudible word]. The initial disposition of the [inaudible words], it’s that the disposition of the center is not a [inaudible word] spot, but it’s a completely empty site, and thus the site, being absolutely empty, can therefore be occupied by all, hence the idea of a complementarity, precisely evokes [several inaudible words] of the empty site; it’s the idea of the agonia, the struggle for the center. And it’s in the struggle for the center precisely that the Plato’s philosophical question intervenes, [inaudible words] and what the selection is that the philosopher is going to make for those who want, or don’t want, consider all that. That’s the comment I wanted to make.

Deleuze: Oh indeed… this is a very useful remark. And, in fact, but… it is certainly, it is even precisely because the center is an empty place that it is where the booty is placed, in a completely transitory way, and where the person who speaks comes to speak and all of that is completely… And indeed, what you add about Plato is quite correct. So much so that, if you grasp this distinction, this historiographical distinction, from a historical, historiographical point of view, between the two: between the space we’ll call magico-religious, and the new space, there is a whole story of alethes, aletheia, which is to say of truth. The mutation of magico-religious truth into philosophical truth. And this is main subject of Détienne’s book, Les Maîtres de vérité dans la Grèce archaïque: the evolution of this aletheia, and I told you about my surprise last time that this book doesn’t once cite Heidegger, whereas it is difficult to see how Heidegger’s contribution to this problem of aletheia for the Greeks would not be of considerable value and something that could be useful even to historians, and in fact I have the strong impression that Détienne certainly uses him. All right, but, well, we don’t have the time and most importantly that’s not our subject. So, you see, then, the second direction was: yes, the cosmic and social space is organized in Greece in such a way that philosophy is born, that a new type of thought and discourse appears that is called philosophical. The friends – giving further support to what Comtesse was saying – the society of friends is around the center, they are the ones around the center. It is no longer the sages, who correspond to the image of the pyramid, it is the friends of wisdom, who correspond to the image of the circle.

And I am saying that there is a third direction because – as one of you signaled to me last time – it is clear that we cannot place Nietzsche on the side of the German philosophers… Because… well in the first place he didn’t want to be. We have to take what he wanted into account, because he himself asserted that there was a radical difference. So Nietzsche is not this… Heidegger is the only one who thinks that Nietzsche thought that… the Greeks… bore witness to the revelation of being, because Nietzsche poses the problem in a third way and, I also stress, one that doesn’t contradict the two others, but it is a third path, a third path which perhaps has its antecedents, I’m not saying that Nietzsche was its founder, he takes it to a very high level, at the end of the nineteenth century… and it consists in a third type of response, no longer about revealing being or organizing a cosmic and social space, but about producing, bringing out, a new type of force.

Here again, this can be reconciled very well with the historical hypothesis: a new type of force will also be expressed in a new space, that goes without saying. Everything we have just said about forces, about the pyramid-shaped organization of forces, etc. And if I try to say, yes, if I try… Nietzsche’s texts on the Greeks are at once so varied, so beautiful… so ambiguous, so… it’s very, very difficult, and I’m afraid it would take a whole session – and there’s no cause to – to try to say what I think about that. I will just try to pick out a few points.

What Nietzsche says to us in the end is that the Greeks, as philosophers, the Greek philosophers – what did they do? I think that one of the most constant themes in Nietzsche is: they invented new possibilities of life. They made thought an art. That’s it. Note that here again, Hegel always said that the immediate revelation of being is the beautiful, and the Greeks… and this was even the theme… the criticism Hegel made of the Greeks: that the Greeks remained at the stage of the beautiful. They apprehended being as beautiful and, according to Hegel, this is inadequate, completely inadequate. And Nietzsche means something completely different, which nevertheless has a kind of resonance. Nietzsche doesn’t say that they apprehend being as beautiful, he says that they make existence an art and that, in so doing, they invent new possibilities of life.

What does that mean? It means, no doubt, two things. That – and this is also a constantly recurring theme – the philosopher, which is to say the Greek, is the one who affirms life. The philosopher makes power [puissance] something that affirms life. It is a conversion of sovereignty. Power no longer means power becoming an art, which means: it is no longer a will to dominate. Pre-philosophical thought, for its part, conceived of power as a will to dominate, that’s the problem of sovereignty. With the Greek philosopher, no, force is no longer a will to dominate. Who wants… Nietzsche launches his great formula, the will to power. He adds: who… who could call that a will to domination? It is not about wanting to dominate, not at all, not at all. “Will to power” [volonté de puissance] never meant, for Nietzsche, at least in the way he understood it, “ensure one’s domination,” but “affirm life.” It is a transformation of power. You can see how that ties in very well with our historical perspective from just before, affirming life and no longer judging life, as the sovereign god does. So much so that the philosopher, in so far as he invents new possibilities of life, can only do this through the following operation: the unity of all that lives. And when even Parmenides said being is – and here he agrees… being has never meant anything else but the unity of what lives. So, breaking with the sovereign conception of power is the first act of philosophy, in so far as it makes life an art, which is to say in so far as it creates new possibilities of life.

And the second aspect is how… what are these possibilities of life? Establishing in oneself a relationship between actions and reactions such that a maximum of action is produced. Establishing in oneself a relationship between actions and reactions such that a maximum of action is produced. And this time it is in opposition to the other aspect of magico-religious thought, namely the conception of the feat of the warrior and of war. “Will to power” has nothing to do with war. On the one hand, “will to power” has nothing to do with sovereignty, and on the other hand, it has nothing to do with war – the two poles of magico-religious poetry that I told you about just before, namely the problem of the sovereign god, the problem of the feat of the warrior, which fall to the level of, yes, philosophy is the affirmation of a new form of life. And this new form of life consists, from the point of view of thought, of thinking the unity of everything that lives.

What I am saying is particularly inadequate in relation to Nietzsche, but never mind, the important thing is for you just to have the sense that there is a new emphasis. And just as I was saying before about the nineteenth century to the most recent authors, I’ll come back now to my real problem: why does Foucault focus on the Greeks in his final books? The response will take some time, obviously, but I know that if he focuses on the Greeks, based on what we have just said – he is very familiar with Heidegger, he is very familiar with the historians of Ancient Greece – but he focuses on them from a point of view directly connected to Nietzsche’s. It is a question of force [force]: if the Greeks invent philosophy, it is because they bring a new conception of force, or they bring out a new type of force. In this respect I think, even when you’re not aware of it, The Use of Pleasure derives from Nietzsche. Only… only while he poses the problem in the same way as Nietzsche, I think his response is completely personal to him and no longer at all a Nietzschean response, it is very different to Nietzsche’s.

And that’s what I would like to explain to you today, the way Foucault conceives the Greeks, then, from this vitalist or dynamic point of view, once again, a new adventure of forces and relationships between forces. Because remember, what was the relationship of forces in Foucault? It was the object of the diagram. It was: all force is in a relationship with other forces for each formation, in all social formations. All force is in a relationship with other forces, whether it affects other forces or is affected by other forces, and both at the same time, there is no force that does not affect other ones, there is no force that is not affected by other ones. So, it is these relationships of force that are captured in a diagram. I am assuming that you remember all of that. And I am asking: is there a Greek diagram?

If you recall, we saw this because it’s a question that came up in light of how rarely Foucault uses the word diagram, in light of the way he defines the diagram in relation to disciplinary societies, which is to say relatively modern ones. We asked ourselves, for our part, in the second semester, we asked ourselves – or in the second term, I don’t remember any more – we said to ourselves: alright, but can we talk about diagrams for all formations? And we said: well of course, of course. Because the diagram is always the determination of the relationships of forces that are effectuated in a social formation, that are realized, in effect, actualized in a social formation. To the point where I am entitled to say that all social formations refer to a diagram, because they actualize relationships between forces. I pose the question: is there a Greek diagram? Yes, there is a Greek diagram, why wouldn’t there be? If there is a Greek formation, there is a Greek diagram. What is new about it? What is the relationship of forces among the Greeks? We have to pay close attention to this book that Foucault wanted so much to unpack because he doesn’t mention these problems, but you can sense that we are in the middle of an attempt to hook up The Use of Pleasure to Foucault’s other books. But he doesn’t feel the need to say it, so we will patch them together ourselves… not patch them together, because I don’t think it is forced, it really is, it is… it is… I think that The Use of Pleasure is an integral part of the whole oeuvre.

So then, this is how I think the Greek diagram could be defined, and it would be very Nietzschean and quite in line with what Comtesse just said: an agonistic relationship between free agents. An agonistic relationship – what does “agonistic” mean? I think that above all we mustn’t confuse agonistic with polemic. It isn’t a relationship of war. What would an agonistic relationship be? It is no longer a relationship of war, which would take us back to the feats of the warrior, to magico-religious thought. Similarly, for “between free agents,” which is say they are not agents who are under a higher sovereign, which would again take us back to magico-religious thought. Here you have something specific. The diagram, the relationship of forces, that corresponds to the Greek city is an agonistic relationship between free agents, between free men, let’s say.

And what would this agonistic relationship, which is not a relationship of war, which is not a polemical relationship, be? Well, we can clearly see that in the Greek city it is a relationship of rivalry. It is a relationship of rivalry. And is it any accident that this word appears in Plato so often? Rivals. The Greeks wage wars, of course, but they don’t think of themselves in terms of war. They constantly think of themselves in terms of rivalry, in all senses of the word and the most concrete ones: political rivalry around a magistracy, rivalry in court, rivalry in love. I think that the fundamental theme of rivals in love starts with the Greeks – not at all that there weren’t rivals elsewhere or in other formations, but in the other formations, it doesn’t seem… possible – I don’t really know – to show that the rival is always thought in terms of something other than pure rivalry.

For those who have studied a little Greek: amphisbetesis. Amphisbetesis is a word that has stood out for me in Plato. What is Socrates’ method? What is the Platonic method, or an essential element of the Platonic method, which to me really seems to mean: what is Greece? It is that whatever the question is, rivals come forward saying: it’s me! it’s me! it’s me! That’s not war, it’s rivalry. I say: what is the most beautiful? The Greeks don’t wait for the sovereign to decide, they don’t decide it by coming to blows either, as in war, it’s not magico-religious thought anymore. No doubt they lay claim to a place, in relationship to which… a place… an empty place which the claimants rival over. I was saying to you: the most fund… or one of the most fundamental texts of Plato’s in this respect is the Statesman. That is where politics is defined as the art… or the politician is defined as the shepherd of men, and there you encounter Plato’s real signature, the Platonic style, there are twelve, twenty, eighty… people, which is to say types of forces, who put up their hand and say: I am the shepherd of men! It’s me! So, Socrates or someone else, whoever is leading the dialogue, says: okay, let’s try to sort all of this out.[3]

When I say: love itself is thought in terms of rivalry, it is very interesting because, in effect, you understand, it’s very different, once again it would be stupid to object that there have always been rivals in love and cite Eastern texts for example. That’s not the question. It would be an objection if you said to me: here are some Eastern texts where the rival in love is really thought in terms of… in terms of and in relation to a pure category of rivalry. Of course, if… if you told me that, that would represent an objection. We would work it out, we would see… or we wouldn’t work it out and I would say: I beg your pardon, I was wrong… But it seems to me, personally… You can see that the agonistic regime is so different from war that where do you find it? You find it in judicial procedures. You find it in the proceedings of love, the process of love. You find it in games, the role of games, the role of the athlete.

And what is Platonism? If we had to give a definition of Platonism, the one I myself would give is: a philosophy… it is really the phi… it is like… it is the realization of Greek philosophy. Why? More than Aristotle, I think. Aristotle is already in a world that… [The gap is from Deleuze] But Plato is the pure Greek philosophy. Why? Because he is the one who oriented the whole of philosophy in the direction of the testing of rivals. How do you judge between rivals? In each domain, who is the one who knows best? So okay, there are domains where it is simple… The shoemaker… hence all of Socrates’ questions, all the technical questions, when he says: well, there’s no problem when it comes to the shoemaker, everyone knows that when it comes to shoes, the expert is the shoemaker. But what about in politics? Who is the expert there? How do we decide between rivals? It’s a practical problem. How do we decide between them, whether it is a matter of rivals in love, in court, other rivals…? That’s the Platonic question. It isn’t… It isn’t: “What is an Idea?” If Plato’s Ideas – with a capital I – are so important, no doubt it is because of their role in this very concrete question: how do we decide between rivals?

I am only saying this to shed a little… light on what Foucault says, very quickly, because in The Use of Pleasure you find this invocation several times: an agonistic relationship between free men. If you’re not paying close attention, you will read it in a mechanical way. I suggest you attach great importance to this formulation each time it comes up in The Use of Pleasure, because we need to see it as the specific diagram of the Greek city, which doesn’t apply to other social formations. This is the specifically Greek thing. An agonistic relationship between free agents, this is a definition that only applies to the Greek city.

And now we find that something follows on from this. So that was my first point in relation to Foucault. I move on to the second point: that something will follow from this definition, or this diagram. What will follow? Well, I can only call it a, let’s say, a detachment [décrochage]. And after all he himself calls it, I believe, a detachment, we will see. Namely: as a function of the diagram – agonistic relationship between free agents, between free men – only a free man can govern free men, and only free men can be governed by a free man. That is the Cleisthenian ideal of the city.

So then, who is the free man capable of governing other free men? Foucault’s answer, based on the Greeks, or rather Foucault’s theme that runs through the whole of The Use of Pleasure, is: look closely at Greek literature, even in the most apparently insignificant forms. The Greeks are people who never stop telling you: the only one fit to govern others is the one who knows how, who is capable of, governing himself. It is obvious that this is only valid in relation to the diagram: free men, agonistic relationship between free men. Who will govern the other? The answer is going to be: well, the only one capable of governing the other is the one capable of governing himself. All right.

To govern himself. Here is Foucault’s trick. Why? Already at this level he has, he has his idea. The idea is this: governing oneself is a very curious operation, because it can’t be reduced to either the domain of power or the domain of knowledge. It is a specific operation, irreducible to power, irreducible to knowledge. In other words, governing oneself is an operation that detaches [décroche] both from power and from knowledge. It is the third axis for the Greeks. It is the third axis. He says it in L’Usage des plaisirs, page 90 [77 Eng],[4] “It would not be long before this ascetics” – governing oneself – “would begin to have an independent status, or at least a partial and relative autonomy” – you see, governing oneself derives from something, but derives while at the same time taking on an independent status. “It would not be long before this ascetics would begin to have an independent status, or at least a partial and relative autonomy. In two ways: there would be a detachment [décrochage] of the exercises that enabled one to govern oneself from the learning of what was necessary in order to govern others.” Governing others is the relationship of power.

You see, we had the “relationship of power” diagram, the relationship of forces. This specifically Greek relationship of forces is the agonistic relationship between free agents. That’s what defines power for the Greeks. Or else government, governing others. And something derives from this. Since government takes place between free men, since the relationship of forces places the free man in a relationship with another free man, the only one fit to govern the other, which is to say a free man, is a free man, another free man capable of governing himself. The government of the self will follow from the diagram, derive from the diagram and become independent. It becomes independent in relation to the relationship of power, that’s another relationship. That’s another relationship. “[T]here was also a detachment of the exercises themselves from the virtue, moderation…” – of the exercises in self-government – “themselves from the virtue, moderation and temperance for which they were meant to serve as training.” What does he mean there? The whole context, moving more quickly, explains it. It is about virtue as a code and virtue as a code of what? Virtue, such as it is for the Greeks, as a code of knowledge.

In short, governing oneself detaches [se détache] from both the diagram of power and the code of knowledge. Governing oneself detaches from both the power relationships according to which one governs the other, and the relationships of knowledge according to which each one knows himself and knows others or the other. A double detachment [décrochage] in relationship to the diagram of power, and in relationship to the code of knowledge. The relationship to the self becomes independent, and this relationship to the self will receive a name from the Greeks at the same time as it becomes independent, all the while deriving… You see, it doesn’t come first, that’s what I want you to understand. It presupposes the Greek diagram. If there wasn’t a relationship of forces, if the Greeks hadn’t invented a new relationship of forces, the agonistic relationship established between free men, which didn’t exist before, if there wasn’t that, an art of self-government would never have derived from it. First you have to have this diagram of power, first you have to have this relationship of power, so that this new relationship of governing oneself derives from it. So much so that… What does that mean and how is it derived? Same page, page 90 [77], Foucault calls the government of the self, the art of the self. The art of the self. This is what derives from the relationships of power, in the original form they have for the Greeks.

And the Greeks call this art of the self, they call it enkrateia. Enkrateia. Which is to say — how to translate it — power over oneself, power of the self. The relationship… is what he also calls the relationship to the self. I would like – yes, one moment I think, [to someone wanting to ask a question] because your question will only make sense if I finish this point, which is the most difficult one. — It’s that… Well, what does that mean? Well, in a certain way, you see, if we try to draw it out, what is Foucault telling us there? Why? He amasses texts, he looks in Xenophon, always this cry, in all the Greek authors, this theme: only the one who is capable of governing himself is fit to govern others.

But you see it would be a gross misunderstanding to conclude from this that the art of self-government comes first for the Greeks. No, that’s not the line of reasoning at all. The Greek line of reasoning, or in any case Foucault’s line of reasoning concerning the Greeks, is that the Greeks invent a new relationship of forces, the relationship of forces between free men. That’s what comes first. And that’s what defines the city. What is the relationship of forces between free men? Once again, it isn’t war, it is rivalry. Second point: what follows from this is the necessity of asking the question, “Who is the free man with the right to govern other free men?” And the response is, necessarily: the one fit to govern other free men is the one fit to govern himself. In other terms, what does the government of the self appear as? Well, it is effectively a completely new state of force which is not included in the diagram. What does that mean? What does it mean to govern oneself?

Let’s try to draw out “governing oneself” a little… it’s that force affects itself. A force that affects itself, that is self-affecting, is self-governing, self-directing. But consider the extreme novelty here: forever, from the beginning of our analysis, we have said: forces have no interiority, all force refers to other forces, either in order to affect them or be affected by them and, indeed, the relationships between forces were relationships between forces external to each another. A force is affected by other forces from the outside or it affects other forces from the outside. That’s the status of forces. If a force comes to affect itself, it is no longer affected by another force, no more than it affects another force, it affects itself and, by that token, it is affected by itself. It is the affecting of the self by the self.

Do you not recognize our whole theme here, to the point where I am almost embarrassed? In other words: force has folded onto itself. Force has bent onto itself. I would say: there was a subjectification. Force didn’t have either a subject or object, it only had a relationship with other forces. In folding onto itself, it performs a subjectification. The subjectification of force is the operation by which, in folding, it affects itself. The Greeks folded force onto itself, they related it to itself, they related force to force. In other words, they doubled [doublé] force and in doing so formed a subject, they invented an inside of force. The affecting of self by self. The Greeks invented the doubling [doublure] by folding, bending force, or they invented subjectivity or even interiority.

And people say the opposite, they say that the Greeks were unaware of interiority and subjectivity. And there is indeed a reason why this can be said, in a certain way. What is it? Well, it’s not very complicated, they invented subjectivity, but in the form of this operation of subjectification by which force is folded onto itself. In other words, it is derivative. The Greeks in effect had no idea of a subject that would be constitutive of anything. Subjectification derives from a state of force. Between free men, the only one capable of governing is the one capable of governing himself, which is to say of folding his own force onto itself. Subjectivity derives from the specifically Greek state of force, from the specifically Greek relationships between forces. In other words, we would say that [recording ends here] governing oneself or the art of the self or the relationship…[5] [Interruption of the recording] [74:53]

Part 3

… Governing oneself, governing others, which is to say the relationship of forces between distinct forces, the relationships of power between free agents, this is what we could call a constituent power [pouvoir constituant]. It’s the constitutive power [pouvoir constitutif] of the Greek city: an agonistic relationship between free men. Governing oneself is a regulatory condition, it is not at all constituent, the proof being that Greece never stopped having tyrants. It’s a simple regulatory condition. That should suggest something to you. I am saying: the rules of power in a social formation are the obligatory rules – you must obey. The rules of knowledge, the code of virtue is, in another way, also obligatory, another type of obligation. But governing oneself, as a regulatory principle and no longer a constituent principle… governing oneself is something else entirely. I would say: it’s an optional rule [règle facultative]. You’re a free man. If you don’t want to govern yourself and if you want to govern others, at that moment you become a tyrant, very well then. You’ll see what will happen. It’s an optional rule.

If you have paid really, really close attention, this should remind you of something. When we were right at the beginning, when we were trying to analyze the very complex notion of the statement in Foucault, I tried to show that the statement could not be assimilated to anything that was known in linguistics, because the statement was always straddling systems, different systems, heterogeneous systems, and so the statement included rules for passing from one system to another. And I cited a case that wasn’t from Foucault, it was from an American linguist, [Willam] Labov.[6] I told you: yes, here for example is a small boy, a little black boy… who in his everyday conversation passes twelve times in the space of a minute from standard American to Black English and back again. We have to say that it’s always like that, that our speech is made up of perpetual transitions from one system to another. But just as each homogeneous system, considered in the abstract, is defined by constraining rules, and these are the only ones linguists are familiar with, so our constant transitions from one system to the other – and I was saying to you that each time we speak, we constantly jump from one system to another – so our constant transition from one system to another is also governed by rules, but these rules cannot be called constraining. Why? Because they have large margins of tolerance, first of all, and also because they are no longer at all defined by an obligatory character.

Hence Labov’s expression, which I found very beautiful: variable or optional rule.[7] And I suggested using this notion to better understand Foucault’s theory of the statement, saying: yes, statements in Foucault refer to variable or optional rules. In another way, if I bring a few things together, you remember that more recently we kept finding how fascinated Foucault was by the idea of something that folds, whether statements folding, as for the poet Raymond Roussel – a proposition that folds onto another proposition – or visibilities themselves folding, and now we are coming across the idea that what the Greeks invented was just this: they conceived relationships of forces in such a way – this is what needs to be said first, you see, I’m still maintaining the primacy of the diagram, which is to say the relationship of forces – they conceived relationships of force – which is to say relationships of force with force, with another force – they conceived it in such a way that it gave rise to the idea of a force that had to fold onto itself, form a relationship, enter into a relationship with itself and no longer a relationship with another force. The relationship of force to itself had to derive from the relationship of force with others. And the relationship to itself was to become, unlike the relationship of power and the relationship of knowledge in virtue, the relationship to the self was to become the optional rule of the free man. The Greeks weren’t unaware of subjectivity and interiority, but it is true that they made it the optional rule of the free man, which is to say they made it the ultimate stake of an aesthetics. Hence Foucault’s pages on the Greeks and aesthetic existence in The Use of Pleasure, where Foucault doesn’t need to mention Nietzsche for his readers to understand that he is referring to Nietzsche and aligning himself with him… and aligning himself with him, but after a long detour that is wholly his own, wholly Foucault’s.

If I try to summarize this long detour, perhaps after all he summarizes it even better, this time pages 73–77 — ah no, that’s subjectification, there’s no… no, that’s still the agonistic relationship, all of that, enkrateia, okay, very well… very well… I am trying to say that… — I haven’t forgotten you, ok? [Deleuze speaks to a particular student] — They folded force. Which is to say they put force in a relationship with itself. If the relationship of forces hadn’t become an agonistic relationship between free agents, this operation would never have been possible, it derives from this new relationship of power. The Greeks derived a government of the self from a government of others, because they posited the government of others as a relationship between free men. Because they produced this sort of diagram and… to the point where – I mean literally – the domination of others among the Greeks is doubled by a domination of the self or, if you prefer, I would say, which amounts to the same thing, force, in its relationship with force, folds in a relationship with itself.

And this is what Foucault tells us… — but where, good lord, I’ve lost… Dear, oh dear… an essential text… — he says something like… — only you won’t believe me because, if I have lost it… — he more or less says… he says… — Ah, I must find it… — You see, the constitution, the Greeks, invent subjectification, but they let it… they let it remain under an optional rule, which is why idiots say: there is no subject for the Greeks. You can see how it is both a very, very long way from Heidegger, and at the same time, this resonates with Heidegger, it is very very interesting… — But now, my excerpt… But I must, I must… dear oh dear… — “Aesthetic existence among the Greeks…” — you will find it especially in 103–105, but I will find all of the quotes I need except that one of course… Dear oh dear… Ah! Perhaps, perhaps… Ha ha! Ha ha! 93–94 [80–81 Eng] — “this freedom…” — this freedom, subjectification – “this freedom is more than a nonenslavement, more than an emancipation that would make the individual independent of any interior or exterior constraint; in its full, positive form it was a power,” here it is, listen to this, “it was a power that one brought to bear on oneself in…” – in! – “in the power that one exercised over others.” That’s precisely what occurs, it couldn’t be clearer. You first have to posit the power over others, and then comes the interiorization or this doubling [doublure], this folding of force which will constitute, in the power that one exercises over others, the power one exercises over oneself. It is as though the relationship of forces folded. If you don’t start from the relationship of forces… Subjectification is derivative. In other words, subjectification or, the perfect formula – and just as I say that, I am going to lose it… I have a feeling I am going to… The perfect formula is… oh dear… the relationship… the relationship with the self derives from the relationship with others under the condition of an optional rule, which is the folding of force onto itself, the bending of force onto itself, the fold of force onto itself.

It’s almost an answer to the question: why does the same man write The Use of Pleasure and Raymond Roussel? Raymond Roussel is haunted by doubling [la doublure] and the problem of doubling – we saw this the last time – and the folding of a proposition on a proposition. I was saying to you the last time that… well yes, the Greeks are the first doubling, to speak like Heidegger, the first world-historical doubling. All right, you need to understand that, you need at all costs… at all costs, but we’ve already done it so… what do I have to add… So! Over to you!

Comtesse: [Inaudible comment]

Deleuze: Personally, I must admit I wouldn’t say that, I wouldn’t dare say that, because it seems certain to me that for the Greeks – unless you want to make them moderns – there is obviously no constituting subject [sujet constituant], which is to say the subject is always derived, and the subject is optionally derived. So, what is primary – and this is what absolutely must be maintained – is the agonistic relationship, that is fundamentally primary. So what is the role of necessity?

Comtesse: Methodologically primary…

Deleuze: No, ontologically primary. If there isn’t… Politically primary in the sense that, here, politics is one of the very conditions of philosophy, because if you bring in the problem “necessity or no necessity,” you see… that doesn’t seem very important to me, because that is a much too general problem in relation to where we are at, it is more a matter of knowing what type of necessity does Greek philosophy invent, which is not the same as the necessity of the previous thought, of the previous type of thought. What is certain is that the relationship of power happens between free agents, whether it is a matter of necessity or not, it happens between free agents, which is to say between citizens. That’s the innovation of the Greek diagram, that’s the new relationship of power, because before, in the imperial formations, you couldn’t say that the relationship of power happened between citizens, and the citizen didn’t even exist, it can go from the great emperor to the man… what kind of man? Would you say the free man? You wouldn’t even say the free citizen, those are different notions. You could say that it goes from the great citizen to the public servant. You could, of course… the public servant isn’t a slave, there is a whole hierarchy, etcetera. But the very idea of a free agent is excluded, so I am much less susceptible… so… now it is undoubtedly a Greek problem, what is the relationship of the free man – which is to say the citizen – with necessity? And on that, we have seen other problems for the Greeks, it works out, it takes a long time for the problem of necessity to be fully articulated, it varies a lot, I think even that, if you are looking for an example where this problem is embodied, it is Greek tragedy, what is the relationship between the free agent and necessity, it is… it is… [Deleuze does not complete the sentence]

But I absolutely maintain – in any case when it comes to Foucault, to reading The Use of Pleasure – it seems to me that we don’t have the choice, it is absolutely necessary to posit and maintain that force, in the first instance, can only be in a relationship with other forces that either affect it or that it affects. If, in the second instance, force comes to affect itself, it is because the relationship, the first relationship of forces, presented original characteristics that made such a twisting of force on itself possible or such a folding of force on itself possible. So, it is effectively a… It’s important to respond because I have the impression that with the Greek miracle, we haven’t all… we’ve never gotten past it… whether it’s Hegel or Heidegger, they have a sort of Greek miracle, whether it is the recent historians, they have a sort of Greek miracle… and here the Greek miracle, you can just get a sense of Foucault’s originality: they bent force onto itself in such a way that force affects itself. So, it is a very modest response. Foucault can laugh, in, in… you realize, in this book, which seems so sensible, but you can’t read it without thinking at the same time of Heidegger’s grand pages on the revelation of Being. That’s why Foucault, in an interview at the end of his life, said: oh, the Greeks… pfft… yes, they’re good, but no need to make a big fuss about it. It’s good, it’s interesting, but it’s not as great as all that. He wanted to say: no, the Greeks aren’t the dawn of being… they did something that was… very interesting, they are the first to have bent force onto itself. So, you’ll say to me as well, didn’t this theme already exist in the East: that to govern others well, you have to govern oneself, etc.? We’d have to examine the texts very closely, what are the virtues of the sovereign… I’m not sure that theme is there, which precisely presupposes a society of free men, that is, pure citizens.

You see, if the relationships of forces aren’t established between free men, force has no reason to bend back onto itself. If it is established between free men, then and only then does the question arise: who is the best free man capable of governing other free men? And the response becomes: the one who has been able to bend force, in other words, the one fit to govern others is the one who has learned to govern himself. But learning how to govern oneself is the art of self or the relationship to the self or, if you prefer, it is subjectification, and it isn’t the same thing as either the relationship of forces, which defines power, or the moral code, which defines knowledge. Here again is our idea: distinct from the axis of power and the axis of knowledge is a third axis – which is what now? Let’s define the third axis as the bending of the relationship of forces or subjectification, which is to say the operation by which force affects itself.

A student: Can I ask a question?

Deleuze: Of course.

The student: [Inaudible comment; he raises the distinction between “lack in power” and “lack in knowledge”]

Deleuze: Could you open it up a bit, I feel like we’re suffocating… Open the window, please, over there…

The student: From the moment that this third level is produced, is it lack… how can we think of lack of knowledge. This isn’t entirely clear.

Deleuze: I don’t understand how you’ve brought in the issue of lack, what’s that doing here?

The student: The question of the non-lived memory, isn’t that also lack?

Deleuze: Why? Why say that?

Deleuze: Because it’s… it’s a memory that [inaudible comments]

Deleuze: Why say that, hm? I mean: why bring in the problem of lack… I don’t see what you are latching that on to in all this.

The student: [Inaudible comment]

Deleuze: The lack of?

The student: Of power.

Deleuze: But where is there a lack of power?

The student: In the free men, who call themselves free, where the center is empty, there is lack…

Deleuze: Ah no, not at all! We would even have to… Comtesse was going quickly because he very kindly sensed that we were all in a hurry but… emptiness [vide]… emptiness, emptiness… If you say it’s lack, you’re joking. If you say, to speak like Heidegger, emptiness is what can’t be occupied by the being [l’étant]. It’s Being [c’est de l’être]. Why would it be emptiness, I mean, it’s not necessarily lack. There is no reason to assimilate emptiness… You see, to my knowledge, Foucault doesn’t talk about lack. Now you can always, if it’s your problem… but, in my view, that would decenter everything if you interrogate something on… You can say that an empty place is empty because it lacks something or someone, but it’s a place, so even if it is a hole, it’s not a lack. A hole is not a lack. It’s a place, which has a location, which is… No, I think that your question in the end must be personal, but there’s nothing I can do about that, I mean, you must yourself have, there, if you pose certain problems of power as a function of a lack… But for Foucault, not at all, his definition of power is: relationships of forces insofar as forces affect each other, end of story. But there is no void, no lack in that…

The student: [Inaudible comment]

Deleuze: Yes. Ah, no, yes, it’s not that. The important thing is, if you like, the important thing is – this is what I would like you to understand – it’s that, in effect, Foucault is responding in his own way to “why is philosophy Greek?” And the Greeks… because it is under the conditions of the specifically Greek relationships of forces that force can, in a derivative way… can, secondarily, fold onto itself or affect itself. To the point where we have almost answered a question that concerned us: in what way is The Use of Pleasure fully part of Foucault’s oeuvre and does not in any way mark a rupture, whatever the change or Foucault’s sort of mischievousness at the end, where his style takes on a sort of serenity. There are reasons… I think there are some very important novelties in The Use of Pleasure, but we are at least in the process of answering part of the question: what it has in common with the rest of the oeuvre. It’s that in The Order of Things,[8] Foucault was constantly haunted by the theme of the fold and unfolding, and on the other hand in Discipline and Punish and the Will to Knowledge, he had pushed a theory of power as far as possible. And then it was like he found himself unable to breathe: how to break through the line? Am I doomed to stay on the side of power? And you can see how, on this point, we will see what that… It’s the Greeks for the moment, but we’ll see what questions all of that poses for us today. He will be led to say: yes, there, that’s it, subjectification or the production of a subjectivity under optional rules, that’s what the Greeks invented and there’s the axis that goes beyond relationships of power.

So, once again, that is the Greek question. Does it concern us? Does it not concern us? That’s for later, because, on that subject, I haven’t… I haven’t finished. So much so that – one last effort, we’ll have a little rest in a moment, but to make it a little more concrete… — Force, then, in a derivative way – you can see I insist on this point – the force that is derived from a specifically Greek relationship of forces, the derived force, folds onto itself in such a way that it affects itself and produces a subjectivity. Once again: subjectification. So, I keep repeating the same formula, this is the last time, because… is it quite clear? I’m very happy to start everything again from the beginning…

The same student: Can I say something?

Deleuze: Of course, of course!

The student: Agonistic rivalries emerge from relations of power, and even emerge from forms of knowledge, and constructing subjectivity… [Indistinct words]. Once freed, once folded back on oneself, and with pure citizens, there is, there will be joy in order to cross the lines of power and to cross the lines of knowledge. And yet, in Nietzsche’s representation, between Apollo and Dionysus, there is a side, despite the joy, of Dionysus’s suffering, there’s his heartbreak [déchirement]. So, this what I come back to when you answer…

Deleuze: Oh, well that, that can be quickly… that can be done very quickly, no problem, no problem at all because, in my opinion, and it’s no big problem, you are mixing up two sorts of text. The texts on Apollo-Dionysus – to recap very quickly – are authentically Nietzschean texts but ones that wholly and once and for all concern Nietzsche’s first book, which Nietzsche repudiated. It was a point in time when he hadn’t discovered anything of what he later calls joy. Untimely Meditations marks the start of the second Nietzsche, which is to say the true Nietzsche, who is no longer a disciple of Wagner and Schopenhauer. It is as though he recants, but at the same time the Birth of Tragedy is still a sublime book… It is difficult, it is out of the question to leave it out of a reading of Nietzsche, but when he discovers the problem of joy, there is absolutely no more, absolutely no more question of the theme of suffering, which is… which belongs to the first period of Nietzsche.

Third remark: does that mean there is no more suffering and no pain? No, but at that point the Nietzschean response changes completely, it’s something I’ve alluded to, it consists in saying that we have to take our pains and sufferings, however terrible they are, within a system of reactions, which enters… or rather, take them within a group, within reactions, flood them with reactions, which makes them enter into a system of actions, where action gains the upper hand over reaction itself, which is to say the construction of a mode of life. He doesn’t mean at all… The construction of a mode of life, which is to say the invention of possibilities of life. For Nietzsche, whatever the suffering, there is always the possibility of inventing a possibility of life, until… until the moment when it ends… okay then, you die, but up until the last moment you invent possibilities of life. That would be Nietzsche’s response, which no longer has anything to do with either Apollo or Dionysus, which has to do with Zarathustra.

So, I think, your question… I’m responding in a very disappointing way, but because… I think it is important for those of you who read Nietzsche to read The Birth of Tragedy but at the same time, each time it talks about suffering, to not forget that these are pre-Nietzschean texts, and it is the only book of Nietzsche’s that isn’t representative of… of his thought as it would become, as it would… It’s a book, as he says himself in Ecce Homo, he says: this book is so Schopenhauerian and it even still smells Hegelian. That says it all, for Nietzsche. That says it all. It still smells Hegelian, it’s a Schopenhauerian book.[9] It’s not a Nietzschean book. The fact remains that you can’t understand Nietzsche without having read The Birth of Tragedy… even if only to measure the progress.

So, what I would like to know if it is completely clear because personally, I’m ready to start again. What you have to understand in all of this is: how there is a new relationship of forces with the Greeks. Secondly: why a folding, a bending of force derives from it. Thirdly, if there hadn’t been the new relationship of forces with the Greeks, the bending of force onto itself could not have happened.

A student: But how does this bending onto itself work? Aren’t we staying there on the level of the virtual? Doesn’t it need to go through the actualization of force?

Deleuze: Excellent. Fantastic question. Well, I say “fantastic” for me because that’s what’s left for me to do. I agree completely. Otherwise, it would be just words. So, allow me, before we stop, to say as well: bending force onto itself, that’s all very well… that is indeed still abstract. Maybe it stays less abstract… it’s that force is like a river, or, even more, it’s like a river, it divides into affluents, and it never folds just once. And if you read – it seems to me – The Use of Pleasure, you’ll realize he doesn’t use the word “fold” [pli] there, there are four foldings [plissements]. Everything happens as though subjectification as the production of a subjectivity takes place with four foldings. Wonderful, it becomes concrete: we are made of four folds, or rather we are surrounded by four folds, we live in four folds, which we make and remake like we make our bed. And you’ll find these four folds, on the one hand, in The Use of Pleasure, pages 32–39 [25–32 Eng], and you’ll find them, summarized, in the Dreyfus and Rabinow book, pages 333–334.[10] It’s just that they are difficult… and so I would like, because we need to move forward, I would like to almost solidify them and, I mean, systematize them. Foucault doesn’t systematize them and no doubt he’s right, but we who are simply commentating, we can systematize them.

There is a first fold that concerns… once again, it’s about…. force folds onto itself. And in folding onto itself, it surrounds a part of ourselves, a material part of ourselves. Force traverses us, it is very simple, you see, you are traversed by forces, force traverses you. When force folds, it surrounds a part of you. But consider – and feel the rising excitement because this anticipates our future work – there is no reason to think that it will always be in the same way; there is no reason to think that the folds are constant. Am I folded like a Greek? Well… that’s a fundamental question. Is there one subjectification or did the Greeks simply invent a subjectification that, later on, could take on all sorts of other configurations? We don’t know, we can only say in relation to the Greeks. We carefully set aside this problem of other modes of subjectification. Until now.

Hence perhaps the question, and The Use of Pleasure, a book on the Greeks, comes back like a sort of slap in the face in its most current form: and now? How do we fold ourselves now? What are your own folds? What do you fold yourself in? Which is to say: how do you produce yourself as a subject? I can say “how do you produce yourself as a subject?” or “how do you fold yourself?,” it’s the same thing… These are ways of saying… so, it works… if you don’t fold yourself well, it doesn’t work. So… The Greeks, I am saying, there is a first fold, the one that surrounds a determinable material part of ourselves. What is it in the case of the Greeks? The body and its pleasures. In effect. Why the body and its pleasures? To govern oneself is first of all to govern one’s body, so the material part of myself that finds itself surrounded in the fold, folded in the fold, is the body and its pleasures, and the Greeks conceived it in those terms: the body and its pleasures, which they called the aphrodisia. Why did they call it aphrodisia? We have to be careful, we don’t know yet. It’s not clear, we’ll leave that to one side. The body, the body and its pleasures, is not only about aphrodisiac pleasures, it can also be about food-related pleasures, the Greeks were very preoccupied with their food. They didn’t spend all their time looking at being! [Laughter] They were enormous eaters! So, the body and its pleasures… but very quickly: do you think a Christian would say that? The part of ourselves surrounded by the fold is the body and its pleasures. No, that’s not Christian at all, only a Greek can say that: the body and its pleasures. To the point where it lends support to Foucault’s case: isn’t there something, after all, we can take from the Greeks, a culture of the body and its pleasures? Many, many have rediscovered the body and its pleasures, perhaps not in the Greek way, or perhaps also in the Greek way.

Why have homosexual movements very often championed the body and its pleasures? As distinct from what? Ah, it’s because a Christian – what does he say? I’m getting too far ahead. A Christian talks about – it is even his invention – the flesh. The flesh, that’s a Christian invention. The flesh and its desires. The flesh and its desires. The body is a site of pleasure. The flesh is a site of desire. So, is there any lack in that? [laughter] The flesh. And there is a whole history of the flesh, but today it is as though, strangely, we have rediscovered it – guess where? What a surprise, in phenomenology. Husserl has great texts on the flesh, and Heidegger also takes up the theme of the flesh. This gives me great pleasure because I always suspected that Husserl was deeply Thomist. It’s not surprising. The flesh and its desires. So, is it an accident that Foucault’s unpublished work is called The Confessions of the Flesh? He already gives us a sign: after the body and its pleasures of the Greeks, there is the flesh and the desires of the Christian. It’s a material part surrounded by the fold, but it’s another form of fold.

So, you see, first fold: the one that surrounds a material part of myself. Second fold – well, I am talking about it like a fold, but it is just as much four aspects of the same fold – this is the rule according to which the fold is made, the rule of the folding. And, indeed, then… You will see it is not quite like that, let me clarify, you will read the text and you will see it is not quite like that – so don’t call me a liar, I will have warned you – but you’ll see it is almost like that. And by the same token you’ll see that if it is not quite how I am presenting it, it is because it is more convenient for me to make it more solid and systematic… All right…

Yes, as for this second fold, the rule of the fold…: “Is it, for instance, divine law that has been revealed in a text? Is it natural law, in each case the same for all living beings? Is it a rational rule? Is it an aesthetic principle of existence?”[11] I would say that the rule of the fold can be the divine law, natural law, the law… all right, let’s say it’s the logos. The rule of the fold for the Greeks as logos. And, in effect, what is logos according to Heidegger’s fantastical etymologies? It’s the gathering, the harvesting, it’s the rule of harvesting.

Third fold: this is the relationship in which, being already a subject in the process of formation, I am in a relationship with the truth, the relationship of the true with myself and the relationship of myself with the truth, with the true. And there again, same question: can you believe that our relationship with the truth… it’s no longer “what is the truth?” It’s “what is our relationship with the true?” Can we believe that we have the same relationship with the true as the Greeks? Obviously not. So, all that already suggests to us that all of these folds… [Deleuze does not complete the sentence]

Fourth form of the fold, or fourth fold: what are we waiting for, for the subject? Because remember [Maurice] Blanchot’s beautiful formulation: when the outside folds, an interiority of waiting is constituted. Folded subjectivity is waiting. Surrounded by my folds, I wait. But what am I waiting for? But there again, I apply my rule of variation: is it the same thing to wait, to be worthy of memory, to await immortality, to await a happy death, to await freedom? Imagine whatever you want – what am I waiting for? That’s the fourth fold. Subjectivity as the interiority of waiting. So maybe it is even… it’s not a list… there is no reason… But, for the Greeks, there are… [Interruption of the recording] [2:01:14]

Part 4

… I don’t think, well, there are only a few raving lunatics who don’t want their memory to disappear. No, it can’t be that, our relationship with the truth, it must be something else – what is it, what is our subjectivity of waiting? Our interiority of waiting? And you, what are you waiting for? So, you can see the swarm of questions. The Greeks with the four folds. Reading Greek literature, I can assign, even with the quite large variations between the Greeks, but I have to ask, almost for each period: how do the folds vary? What are the new folds? What are your folds? Which folds? Do you live as though surrounded with folds? Hence the choice – you remember the text I read you the last time, the comparison that Foucault made between Raymond Roussel and Michel Leiris? The more prudent one, Michel Leiris, surrounds himself with folds, surrounds himself with folds inside which he finds absolute memory. And the other, with a fundamental imprudence, undoes the folds to enter into the unbreathable void and there find death. Maybe we are even perpetually engaged in an activity where we don’t know whether we are surrounding ourselves with folds or undoing the folds. We don’t really know.