February 5, 1985

Let’s return to the simplest example, Godard. A series of everyday attitudes tend towards a limit, their theatricalization. It’s not at all like a shift from everyday attitude to the theater. It is not a passage to daily life, from everyday attitude to the theater. It’s a trial of the theatricalization of everyday life. It is a process of theatricalizing of the everyday attitude.

Seminar Introduction

As he starts the fourth year of his reflections on relations between cinema and philosophy, Deleuze explains that the method of thought has two aspects, temporal and spatial, presupposing an implicit image of thought, one that is variable, with history. He proposes the chronotope, as space-time, as the implicit image of thought, one riddled with philosophical cries, and that the problematic of this fourth seminar on cinema will be precisely the theme of “what is philosophy?’, undertaken from the perspective of this encounter between the image of thought and the cinematographic image.

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

After reviewing earlier key points, Deleuze recalls Barthes’s commentary on the senses of “obvious” (obvie) and “obtuse” (obtus), linking the latter to the gesture’s definition and then outlines four questions arising from this connection, especially given Raymonde Carasco’s interpretation of Barthes. Carasco as guest participant “converses” with Deleuze on these questions (for 48 minutes), maintaining that the sense of “obtuse” passes through writing (écriture) or poetic art, attempting to explain how this “sense” emerges in Barthes’s reflections. She also reflects on the importance of a rhythm concept for understanding poetics of cinema which she links to a global mental film image or totality in different filmmakers and also to Blanchot’s sense of images’ duplicity. Deleuze then reflects on two of Barthes’s examples, considering the types of “masks” revealed by characters within the photo stills selected by Barthes, for Deleuze, a way of teasing out an understanding of the “obtuse” as a kind of limit. Exploring this understanding as a kind of fabulation, he refers to Quebec filmmaker Pierre Perrault and his “cinema of the living”, and then reflects on political cinema, third world cinema, (cf. Jean Rouch). Returning to Godard for what Deleuze calls a “cinema of attitudes and gestures”, he moves from attitude to gestus as in Godard’s forms of theatricalization, and also a cinema of politics which has inherent links to the kind of fabulation that Deleuze emphasizes. [Much of this development corresponds to The Time-Image, chapters 6 and 8.]

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Cinema and Thought, 1984-1985

Lecture 12, 05 February 1985 (Cinema Course 78)

Transcription: La voix de Deleuze, Laura Cécilia Nicolas (Part 1), Désirée Lorenz (Part 2) and Pierre Carles (Part 3); additional revisions to the transcription and time stamp: Charles J. Stivale

Translation: Graeme Thomson & Silvia Maglioni

Part 1

… Who knows the dates of the mid-term vacations? I think that there are students here who frequent other departments, right? Or other courses? No, no. Everything’s clear.

So, we’ll have an active break this time that won’t consist in you going across the concourse for coffee but instead I’m going to ask three volunteer messengers – three, because of possible contradictions – three messengers to go across the concourse and report back to me the dates of the vacations, the main question being… please understand how important this is… do they start on the 11th? Will we already be on vacation after this session? Or do they start on the 14th, in which case we still have one session? This isn’t a minor question, it’s a very important one. But I have the feeling that there are some here who should know…

Student: I think it’s the 11th.

Deleuze: You think it’s the 11th? I think it’s the 11th too.

A student: No, I don’t think so.

Deleuze: We can decide on the 11th… and if it isn’t the 11th, that would make it three weeks. That sounds reasonable but it’s better to confirm it. No, perhaps I’m not going to send you because you’d tell me it’s the 14th. You’re not a good messenger.

A student: [Inaudible remarks]

Deleuze: What?… Oh, well then, fine. So, three of you will ask for confirmation… this is what we should do. Okay.

Student: [Inaudible remarks]

Deleuze: It’s chilly, isn’t it? Well, let’s move on. I’d just like to make it very clear to all of you how the different elements of our current research link up. This is precisely what I’d like you to bear in mind for today’s session. For some time now, we’ve been searching for a formal definition of the series, a formal definition of the series. Once again, it wasn’t simply a question of taking the characteristics of a musical series and applying them. In terms of the problem of images, it was a question of constructing our own criteria for the series, making use, naturally, of certain notions borrowed from music, but no more than that. And the formal definition of a series was: a series of images reflected in a concept, genre or category, or rather in something that functions as a concept, genre or category, something of the order of images.

To this, we added two remarks: this concept, genre or category could perfectly well be individualized or personalized. And, secondly, the series thus defined – as a sequence of images reflected, or reflecting in a genre, concept or category – could be constructed in two ways: horizontally, where the genre appeared as a limit, or vertically, where the genre itself constituted an autonomous series, in which case two series were superimposed.

Examples were provided by or in Godard’s cinema, the horizontal construction being of the type: a sequence of images reflected in a genre, this genre intervening as a limit, for example theatricalization as a limit of everyday attitudes in a film like Une femme est une femme [1961]. In the other type of series, the vertical construction appeared when the limit or, rather, when the genre – instead of functioning as a limit of the preceding images – itself developed into a series, into a sequence of images juxtaposed with the first sequence, and this was the case with the two superimposed sequences both in Passion [1982], where the genre itself provided a pictorial or para-pictorial sequence, and even more clearly in Prénom Carmen [1983] where the genre itself produced a musical sequence in which the other sequence of images was reflected. So, there was a superimposition of series, a vertical construction of the series.

So, this is what we had attained… unless some of you want to go back over it, in which case all you have to do is say so. But as I was saying, we haven’t solved the whole problem through this formalism of the series, or through this formal determination of cinematographic series or series of images. We haven’t solved everything, because we still have one problem: not what constitutes the form of the series, but what will be the content of the series, what is the content of the series and no longer what is its form. And from the point of view of content, we established or constructed… through certain texts that we looked at or began to look at last time, we constructed a second type of definition that was a material definition rather than simply a formal one. This time, a series appeared as a sequence of attitudes reflected in a gestus. Note that luckily enough these two determinations echo and even refer to one another. We’ve only gone far enough to intuit these. I mean, given that the series is a sequence of images reflected in a genre, the question of content is: What kind of image can be reflected in a genre?

The first answer, which we haven’t explored at all, but which for us represents a working hypothesis, is that the sequence of images that are normally or regularly destined to be reflected in a genre are images that present bodily attitudes. But taken in terms of their content, that is, taken as attitudes, in what are they reflected? As we were saying, they are reflected in what we call a gestus, a gest. And here again, there was a new correspondence, so it was a reason for us – from the moment we grasped, or even sensed, these correspondences – it was a reason for us to tell ourselves we were on the right path. Because, in fact, there is a new correspondence between genre, or concept, from the point of view of formal definition, and gestus, from the point of view of material definition. Why is this? Because it seemed to us that this gestus, in the work of the very author from whom we borrowed this notion, namely [Bertolt] Brecht, was implicitly linked to the idea of a coherent discourse corresponding to attitudes, where the coherent discourse was implied…. where the virtual discourse was implied by a bodily attitude, or more precisely, as Brecht put it, where the decision was presupposed by the attitude. So, our two definitions, the formal definition and the material definition, could be mapped out quite closely. Again, I want to insist on this, so it all becomes quite clear.

And so we’d have a kind of double difference. I mean, the series became a kind of very delicate narrow thread, a very taut thread that passed or zigzagged between – how shall I put it? – it zigzagged between things, between givens from which it stood out. It zigzagged between what it was not. You see where we are: if it’s true that the series is formally a sequence of images reflected in a genre, but not every image can be reflected in a genre, and if it’s also true that the series is precisely a sequence of attitudes reflected in a gestus, the series is therefore a void between things that it is not, and with which it must not be confused.

So, thirdly, we need to define the series in terms of a set of differences and distinctions it maintains in relation to the things it should not be confused with. And at this point, we could identify those things with which neither the series nor the elements brought into play by the series should be confused. The elements brought into play by the series are: image, insofar as it is reflected in a genre, and attitude insofar as it is reflected in a gestus. Notice how there’s a literary advantage for us in all this, a literary advantage this time that will enable us to define what we call a gest, or the gest, in a way that, so it seems to me, is much more, much more… well, that’s different to the way it’s usually defined. I mean, a certain number of literary critics have taken an interest in what has been called a gest, the origin of which appears to be Scandinavian, though there are also Greek gests.

And gest is not the same thing as the epic, it’s not the same as myth, it’s not the same as tragedy, although the epic has elements of gest, as does tragedy. And what we call gest, a gest, is a very special genre in literature, hence the interest for us in trying to find a definition for this term, and for the moment, the one we do have is a story in which various attitudes are reflected. Gest would be like discourse, the discourse in which a series of attitudes are reflected. But then, I always come back to the question, in distinction to what? You see, I have three levels: the need for a formal definition of the series, the need for a material definition of the series and the need for a differential definition of the series. By differential, I only mean to assign the differences between a series and what doesn’t constitute a series, what isn’t a series. Is that clear? I feel I’m being very clear this morning.

[Someone arrives late]

Deleuze: You’ve missed the clearest part. That’s a pity.

Student: What are we talking about?

Deleuze: What are we talking about? Well, what the series and the terms of the series as we’ve just defined them must be distinguished from… So, I would say there are two things. On one hand, attitude must be distinguished from any lived state, attitude must be distinguished from lived experience. And lived experience has two meanings, very generally, and here I’m not referring to anything in particular… I’m just saying that, conventionally speaking, lived experience can be considered in two ways. Either it’s… [Recording interrupted] [18:42]

… it’s a question, right? But you can see what we mean by the lived experience of a real person. Like your experience, or mine. Or else a supposed experience, the supposed lived experience of a fictional character, in which case the experience corresponds to a role. For example, a fictional character on the screen or in the theater plays a role, the role of a character who’s grieving. The grief is the fictional character’s lived experience insofar as this fictional character is the role played by an actor. I would say that attitude must be distinguished from these two aspects of lived experience, real experience and fictional experience. Why do I say this? It’s obvious. An attitude is not part of lived experience. We constantly take attitudes from experience. But an attitude is not experience.

On the other hand, if attitude is to be distinguished from experience, in the same way gestus must be distinguished from the story or, what amounts to the same thing, the action. And here again, histoire has two meanings. Sometimes it means story, the plot of a fiction, sometimes it means history, meaning the historicity of human deeds. Well, gestus can be distinguished from both story and history. And why is this? Because it’s not an action. It doesn’t fit into the scheme or the sequence of actions and reactions, whether fictional or historical stricto sensu. As we saw last time, following [Roland] Barthes’ remark, Mother Courage’s gestus is not the Thirty Years’ War.

So, there you have it, my three determinations: formal determination, material determination, differential determination. And so, the last time, granted this clarity, this absolute clarity, the last time we ventured into the obscure. It was a question of trying to understand this attitude-gestus link insofar as it distinguishes itself on one hand from lived experience and on the other from story/history or action. And so, we ventured into a much more obscure realm where the following things occurred. After a quick examination of Brecht’s text, which already raised a number of problems for us, we moved on to a commentary by Barthes. Barthes’ commentary suited us insofar as he told us, in one quick sentence, that the gestus is a “coordination of attitudes”, and that the gestus is a signifying gesture, like Mother Courage biting the coin to check that it’s genuine. Okay, this helped us advance a lot, but at the same time it didn’t help us advance, it left us running on the spot. It was a confirmation that there was a fundamental link between attitude and gestus, independent of experience and historicity.[1]

Then we moved on to another Barthes text, this time distinguishing between the obvious meaning and the obtuse meaning.[2] And with much hesitation, we said to ourselves: Wouldn’t there be a link between these two texts, and wouldn’t the meaning – what he calls in a very mysterious way, it seemed to us, the obtuse meaning of the image – be a way of characterizing the gestus? And why did we say this? Because in all of Barthes’s examples, the problem clearly focused – and this was even our reason for comparing the two texts – the problem clearly focused on the notion of attitude. These were images that represented or presented attitudes. And it was regarding these images that Barthes distinguished between an obvious and an obtuse meaning. This raises four questions for us, which I’m not going to deal with on my own.

The first question, which is very subsidiary – I’ll give you all four, and then we’ll see how we can manage – the first question is very subsidiary: Is it fair to bring Barthes’s two texts together and establish a link between them, given that Barthes himself doesn’t establish a link between these two texts? I say this question is subsidiary because, in short, it can only be answered after we’ve answered the other questions. So, far from being the first, it will be the last. It will no longer be a problem. We’ll only be able to answer yes or no after we’ve answered the other questions.

Second question: What does Barthes… what does this obtuse sense that Barthes invokes consist in? I tried to explain why I didn’t understand, or even see very clearly, what he was speaking about. So, it was vexing for me. After rereading the text, I see even less well, so it’s getting worse and worse. Third question. Sorry, second question… What is this… what is this obtuse meaning? Even I understand well how subtle this is… I don’t ask for definitions, just for impressions, because Barthes doesn’t summon definitions, he summons impressions. He doesn’t want to impose his point of view. He says, this is how it is for me, fine, no problem. That’s all we ask, to try to understand what he sees or what he’s in the process of seeing.

Third question, where Barthes’ thesis becomes solid… supposing we have understood the obtuse meaning of the image, he says it has a privileged relation with the still. Not only a privileged relation with the still, but that it can only be grasped by and in the still. This is a very solid, very clear thesis. We don’t yet know what this obtuse meaning is, but what we can say is that, in any case, it can only be grasped in the still. Well, that’s very clear. Many questions arise for us at this third level. Does this mean that the obtuse meaning of the image is a characteristic of photography?

That’s not what Barthes means. So, what is the difference between a still and a photograph? It will be important for us to use of our series of problems to try and make some headway on this obscure question. Everyone knows that a still is not a photograph: what’s the difference between a still as a cinematographic element and a photograph? Barthes raises the question and deals with it in a little note which he leaves incomplete and he knows this full well.[3]

And continuing with this same group of questions, in his consideration that the obtuse meaning is fundamentally linked with the still, Barthes draws the idea that the obtuse meaning and the still constitute the filmic in its pure state, the filmic in its pure state, beyond all actual films, that is, purely filmic or – how shall I put it? – supra-cinematographic. And he goes so far as to say that cinema hasn’t begun, that cinema remains in its infancy, because it hasn’t yet unveiled or attained this pure element of the filmic, whose secret refers back to the still. What can this mean? You see, this third question concerns the relation between obtuse meaning and the still, and what constitutes the status of the still. Can we invoke the still to erect the notion of a supra-cinematographic filmic?

Fourth question: this pure filmic or, if you prefer, the obtuse meaning as it appears in the still, would be precisely a pure filmic because it lay beyond the movement-image. And being beyond the movement-image, the filmic could not therefore be defined by the movement-image. Here too, Barthes’ thesis is very solid. What’s more, it would also be beyond the time-image, at least in the sense of temporal succession, or chronological time, beyond the chronological time-image.

And now, following in Barthes’ footsteps, Raymonde Carasco, commenting on Barthes’ essay on the obtuse meaning, wants to go even further and tells us that this pure filmic is not only beyond the movement-image and beyond the chronological time-image, but beyond the time-image altogether, beyond all time-images, that is, beyond what I believe she calls inner duration, beyond duration or, if you prefer, according to what we covered last year, beyond what I would call non-chronological time.[4]

These are the three points, and the fourth, and the first and the fourth which depend on them, but these are the three points we’re going to deal with, relying on our excellent method, so we’ll now do… we’ll again conduct a sort of interview. But at the same time I’d have to… at the same time it’s not to pose any limits, but I’d like you to agree to respond to these questions, which doesn’t mean you can’t ask others of your own, or make your own elaborations. So, okay…

[Moving away from the microphone Deleuze changes places with Raymonde Carasco. Deleuze can be heard speaking as he sits down again]

Raymonde Carasco: It’s hard swapping places!

Deleuze: … So, the obtuse meaning, we talked a little bit about this last time. I’ll summarize the position… [inaudible remarks] You, you have your position… [Inaudible remarks] you see, you feel what it’s like… [Inaudible remarks] okay. All I had left was… [Inaudible remarks] once said that it concerns a sensation, to say he has this kind of sensation, it’s a feeling he has… [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Well, I think we’re getting into… the obscure, let’s say. How do you discover the obscure, as Blanchot would say? It seems to me that I had a kind of amorous relation with this text, which enabled me to… Barthes’ text – which in a way enabled me to crystallize the research I’d done on a text of Eisenstein – that appeared in Cahiers [du cinéma] a long time ago and was on this text. So, well…

Deleuze: Can you tell us a little bit about what this text is about… it’s a text that has aroused a great… [Inaudible remarks] it’s a greatly felt text… [Inaudible remarks] you can feel it, you can really feel it.

Carasco: Putting it in these terms makes it sound like we are trying to avoid the issue.

Deleuze: No, no, this is what’s missing… [Inaudible remarks]

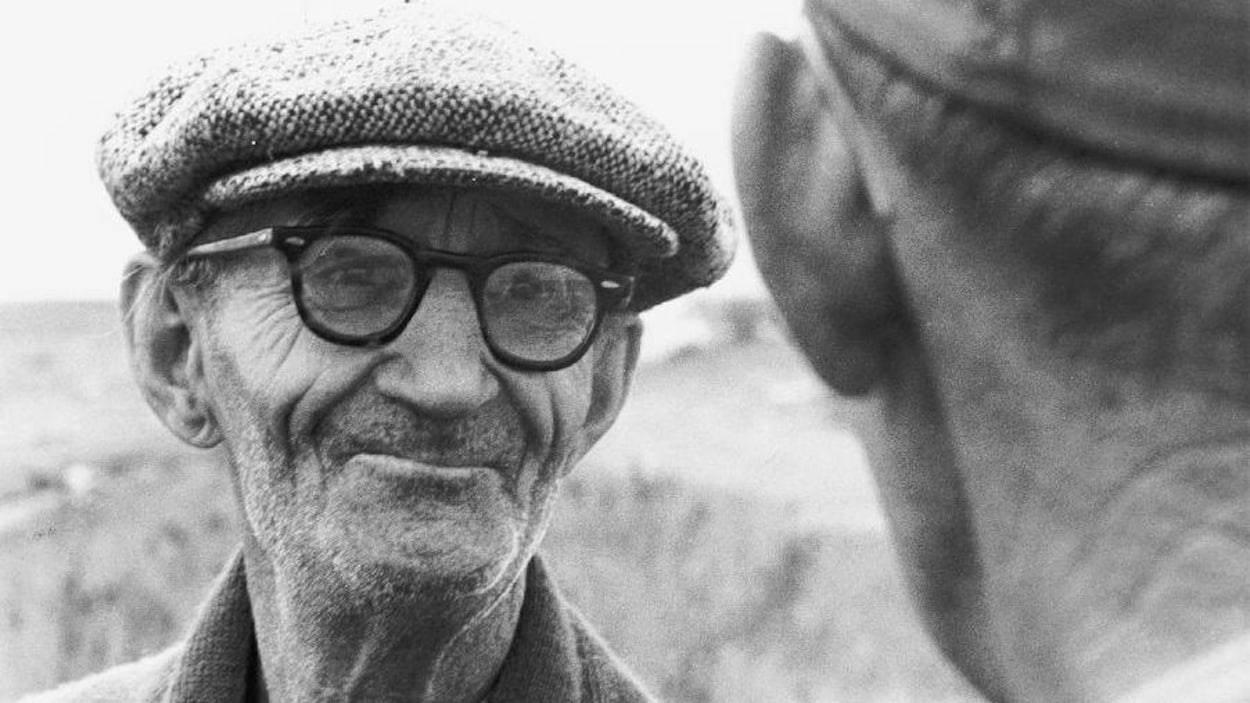

Carasco: And… well, I think it comes down to my affection for a text, Barthes’ text, this affection which is perhaps of an amorous order – in Barthes’ sense of the word – of what this text could provoke, the pleasure of the text. That said, it’s a bit of a cop-out to say that. I’m not sure what you mean when you say “I don’t see it”. That is, if you ask me, Show me this image – the old peasant woman… what this “obtuse meaning” is, well, I’m not sure that it really falls under the order of seeing. Even what Barthes says, since he says it himself, when he takes the example of the old woman – we agree that this is what spurred him to write this essay – it seems to me that what Barthes says… he says that it “cannot be described”. You need the image. If there isn’t an image… if there isn’t an image, you can’t read the text in this way, without the image in front of you. It means nothing if there’s no image, so it has something to do with seeing… well, at least in the immediate sense of the word. But he says afterwards, he says afterwards, he says, finally he says, very well… [inaudible remarks] that it lies between saying and showing. He says that it is an anaphoric gesture, it’s a pure showing [monstration], which doesn’t have… it’s a gesture without a determined meaning. It’s a pure showing that designates not an elsewhere of meaning, but something that is beyond meanings that have already been catalogued, coded and known.

I don’t know how to deal with it, because it seems to me that he himself says that it cannot be described – I made a mistake earlier – he says that it can’t be described, it can only be said. So it comes down to this: to express the obtuse meaning, one has to write. It falls under what he calls the text of writing. It comes through writing, through a kind of poetic act of writing his text. So, then…

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Well, “Drawn mouth, squinting eyes, Kerchief low over her forehead, she weeps”.[5] Well, it seems to me that this… this enigma, the unusual aspect too, what ultimately is the exciting side of what Barthes is saying, is something that in a way he says you can only see “over the shoulder” – like looking over the shoulder of someone writing – so it’s something between “seeing” – because you need the image, it’s a still – and, he says, “showing it” (a gesture). Perhaps there’s an internal relation here with gestus. I’m thinking of these two fragments of… these two poems, two lines by Hölderlin that say: “Man is a …”, what’s normally translated as “sign” – I don’t know German at all – “is a sign”, and in fact [Gerard] Granel in the French translation translates this “sign” as “monster”, in the sense of monstration [showing].

I think it’s the question of the sign that’s being raised here, that is, of a sign that is visual, or at least that begins from the visual, from the visual image and that in a way would be, could we say, a sign-principle, a pure sign, a sign whose meaning and significance has not yet been redetermined, and that is perhaps therefore still indeterminate, not yet determined? Well, when I put it like that, I don’t know if it clarifies anything.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks] … that raises another question that we can pursue… It marks a first difference between us… [Inaudible remarks] I have the feeling that what I understand is very different from what you understand… [Inaudible remarks]

So, we can move on to the second question: How do you manage to link the two… [Inaudible remarks] You say that it’s not exactly a matter of seeing, it’s a seeing-shown, it’s as if the eye is shown something. I agree. But I’d like to ask you a question: Are we supposed to see this in the course of the film, or are we supposed to stop and wait for the still?

Carasco: Well, excuse me, but Hölderlin ‘s phrase was important: “Man is a monster deprived of meaning… is a sign”. But, if you’ll forgive me, the etymology would seem more like monster. So, it’s an etymology that refers to people who… [Inaudible remarks] and Granel gives the etymology [inaudible remarks] as “monster” and not “sign”. Well, it’s more that it’s deprived of meaning, so it’s not a question of meaning.

So, I come back to your question. If, like everyone else, I read Barthes, if I read Barthes literally, I’m obliged to answer… For Barthes – and you have to hold on to this, I think you have to hold on to it first, and even not just at first but all the time – all the time you have to hold on to this literalness of Barthes, meaning you can only see it in the still. In any case, what’s important is that it can only be seen in one still, one still only, and outside the film. That’s what Barthes says, and well, I can’t say anything other than what he says, so this is what he says, well… that’s Barthes. At least, I permit myself to see something else.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Sorry?

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Well, he says he saw it in a photo in Cahiers du cinéma, that is, outside the film, and that when he goes to the cinema, he doesn’t see it anymore.

Deleuze: Well, that’s different. He saw it in a photo…

Carasco: He saw it in a photo.

Deleuze: … and not on a still.

Carasco: My hypothesis, my personal feeling, is that if he had a slightly more trained eye, that is… if he had worked at the editing table, if he were a filmmaker, and if he had worked at the editing table, still by still, the old woman, well, maybe he’d see her in the film in motion. And I think that, after reading Barthes, this obtuse meaning is something I’ve seen in films a few times…

Deleuze: You can see it in the course of the film.

Carasco: That’s where I differ from Barthes. That said, I don’t think this difference is essential. It’s the third level, in a way… I think that whether we can see it, or when Barthes doesn’t see it, I don’t think it changes Barthes’s initial assertion, which seems to me to be related to the question of the still, namely that we can see it simply in a single still and therefore not between two, or between several… that the obtuse meaning is not a friction or collision or the serial-movement of two or several…

Deleuze: … that there is no rupture of relations.

Carasco: So, it seems to me an interesting question because I don’t feel that way, the way Barthes feels. But, at the same time, I say to myself that it doesn’t take anything away, it doesn’t in any way restrict the question in Barthes’ text on the obtuse, which he defines quite clearly as within a single still, and not at all as interval, collision, shock. So, it seems to me that…

Deleuze: So, let’s move on to what you think, since you accept, since you say so in a sense… [Inaudible remarks] So that was the first question, provisionally resolved. Second question: Do you, then, believe that the word “obtuse” is fundamentally related to… [Inaudible remarks] Even if you can grasp it in the course of a film, for itself, in itself, does it have a fundamental relation with… [inaudible remarks]?

Carasco: Well, insofar as I’ve, let’s say, merged the meaning of this text by Barthes [with Eisenstein] in order to read Eisenstein, that’s obviously the way I’ve merged them. That is, it’s not so much the development or analysis of the image that interests me, but it’s actually the entity – I don’t know if it’s a concept or a category – the entity of the filmic. I don’t think it’s a concept, no more than the obtuse meaning. I think it’s…

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Yes, well. But it seems to me that the obtuse meaning and the filmic, which would be the basis of the obtuse meaning… the notion he proposes at the end of the text, almost on the last page, which is the densest part, this is what interests me, what interests us all. The rest is the writing, the pleasure of the text, but this is Barthes’ own impression, I hold onto that, yes I hold onto it, the idea that the obtuse meaning and the filmic are fundamentally and radically linked to the still. That’s what I think is important in Barthes’ text, otherwise it’s not that interesting.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Well, I don’t know what I’ve said. But I’ll try to say it differently.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: What?

Student: [Brief inaudible question]

Deleuze: Yes, the filmic… [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: In any case, in my view this is… this is the core of Barthes’ text. Either we agree that it’s interesting and says something important for our thinking about cinema, and that’s it, or it doesn’t say anything and we have to move on and find something else. But then, it seems obvious to me that it’s that…

Deleuze: Or nothing!

Carasco: … that it’s that or nothing, yes!

Deleuze: So here we are… [Inaudible remarks] and now we go on, because we have other questions… [Inaudible remarks] So, for you, what’s the difference between the still… [Inaudible remarks] between the filmic and a photograph, given that Barthes… [Inaudible remarks – Here Deleuze comments on how Barthes remains deliberately vague on these distinctions]

Carasco: Well, I’ll say right away that I don’t know how to answer that, but I do know that it’s the kernel of the question. So, I’ll try to say some things that I know, and that I don’t think illuminate the difference, alas, between a still and a photograph. I don’t like photography at all. I’m the opposite of Barthes in this, I detest photos, I don’t like photos. Really, I’m not interested in that, I’ve never read anything about it.

Deleuze: Me neither, me neither… [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Well, having said that, there’s one thing I’d be able to formulate a little – it’s just banalities but there we are… – it’s that I clearly understand not what a still is, but the between of two stills in relation to cinema, it’s… if I hadn’t read Barthes’s text, or if I put it out of my mind, well, if I’m asked a question, if someone says to me: What is cinema for you? What is the key cinematographic element? I’d say, not only… – I’d be very Eisensteinian in the end, as always – I’d say that cinema is montage. And what interests me is that for there to be montage… for there to be montage… for Eisenstein it’s always the out-of-shot – not at all the off-screen – but ultimately the shock, the collision of: first, an element, second, the figurative, the visual image, the still if you like, and then, third, what arises, but which is not of the order of the visible, or the image, or the still and which would perhaps be of the order of the concept, in any case, a third term. So, if I were asked what is the key cinematographic element, I’d answer, it’s the interval, the interval between two stills. So, it’s the interval, well, but… or it’s the out-of-shot… – ah, I think I’m getting somewhere now – it’s the out-of-shot as something included, first of all, in the horizontal succession of stills, like the interval between two stills, the shock between two stills. So that would be…

Deleuze: You mean between two stills or between two images?

Carasco: Between two images or stills, I’m saying they’re the same thing.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: If I extract a still, as Barthes does, or if I isolate it at the editing table, it seems to me that cinema begins, or is born, from the shock between shots, well, between images, but at the elementary level, between two stills. I think it starts there, it’s born there. But that’s not what Barthes says.

Deleuze: So, there we have… [Inaudible remarks] for the moment, we have… [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Anyway, I’d like to finish because an idea came to me… what interests me in Barthes is what he calls the vertical reading within the still. And when he himself takes Eisenstein’s phrase about the counterpoint of audiovisual montage, and says that, in the end, we can transport what Eisenstein says regarding audiovisual montage, that is, images and sounds, sound cinema, as early as 1928, in the famous manifesto he wrote with [Vsevolod] Pudovkin and [Grigory] Alexandrov, when he finally says that what’s new is the verticality that sound introduces, when it falls upon the image in a concept that…

Deleuze: It’s not The Manifesto we’re talking about?

Carasco: No, that’s a text from 1938. But still, there’s already this in audiovisual counterpoint, the idea of a contrapuntal montage. I think Eisenstein used the term…

Deleuze: Ah, yes, in a very different sense, but I think we would agree… [Inaudible remarks in which Deleuze seems to be summarizing Eisenstein’s text known as The Manifesto]

Carasco: And that’s what invokes… what invokes… Well, that’s what seems central to me. Because for me, what interests me is Barthes and Eisenstein, the third meaning, the obtuse meaning and Eisenstein. So, this is the fundamental center of gravity, says Barthes regarding Eisenstein, in the text on audiovisual montage. I apologize for the confusion, it was my fault, so I completely withdraw…

Deleuze: Ah, there’s no need…

A student: [Inaudible remarks asking her for the exact reference]

Carasco: It’s in Cahiers du Cinéma 222, with reference to 218, the center… the text Barthes quotes in “The Third Meaning” is by Eisenstein.[6]

Deleuze: So, it’s in Cahiers du cinéma 150…

Carasco: I think it’s called “Montage 38”.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: “The basic center of gravity…” – so says Eisenstein of audiovisual montage – “is transferred inside the fragment… into elements included within the image itself. And the center of gravity is no longer the element ‘between shots’ – the shock, but the element ‘inside the shot’ – the accentuation within the fragment”.[7] And taking this fragment, this quotation from Eisenstein, written it seems in 1938, in terms of audiovisual montage, he says: Finally, I take this fragment and I displace it onto the still, given that there is no sound, and that the obtuse meaning would fall on the visual image just like the sound and… on the interior of the fragment, and thus allow a vertical reading, as he says, of the still.

Deleuze: And even the fundamental form of… [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Yes.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks] … not only the fragment, but an interior of the fragment… [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: In my view, this is the core of what’s interesting about Barthes’ text, his proposal of a theory of the still, based on the filmic.

Deleuze: So, the still gives us the interior of the fragment…

Carasco: Yes, that’s what interests me.

Deleuze: So, the last question: the interior of the fragment… [inaudible remarks] in the still, it’s beyond the movement-image, and according to you, beyond the time-image…

Carasco: Beyond the movement-image, I think there’s no need to… it follows, let’s say, from what Barthes says, beyond or beneath… Well, literally speaking… [Recording interrupted] [1:00:42]

Part 2

Carasco: Let’s say, in terms of the logical, diegetic time of the story, well, that’s obvious too. Is it obvious to you, this first level of time?

Deleuze: Actually, it’s not that important. You see, for me, the problem is… [Inaudible remarks] something else… sometimes the movement-image, sometimes the time-image, and there’s nothing else… [Inaudible remarks] If I’m told there’s something beyond or beneath the movement-image and the time-image… [Inaudible remarks] So, I would refer them back to you…

Carasco: I have to say that when I wrote the text we’re talking about, that is, the one in the Revue d’esthétique,[8] it was the first year, the very first year… it was during the period when you were beginning to work on the time-image, sorry, the movement-image, and you were beginning to distinguish between time-image and movement-image. So, it was, well, that’s why I didn’t, I didn’t quote you, for example, so as not to talk nonsense, let’s say… so as not to make someone say something they didn’t say.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Well, what I’m trying to say is that what I call the time-image is not something that we covered in the work you did last year. So today, I’d say… I’d probably see things differently, not only because of this work but, let’s say, in the very reading of Barthes’ text. I think I went a bit too fast, or too far. I overstepped the mark.

But there’s still something I’d keep, aside from the objective, chronological time-image or the story, well, logical time, objective time. So, that’s how I saw things, how I saw then… how I saw it at the time I wrote it, what it corresponded to, the temporality of the film. Well, it’s obvious that objective time, what Eisenstein would eventually call metric editing, the fact that it’s an hour and a half long, that you can measure each shot in seconds and see the relations between shots – well, the quantitative, objective and measurable level, the metric level of the film, isn’t what’s interesting. So, what I called duration – that’s why I introduced the term duration, taking it roughly from Bergson, let’s say… – what I called the duration-image or the duration of a film or the temporality of a film, I think I could say that it’s perhaps, it would correspond in any case, to what Eisenstein called… [Recording interrupted] [1:04:52]

… objective, metric and so on… it would be something that would probably have to be centered around the notion of rhythm. It would be a film’s own rhythm, its internal rhythm. So, each time, of this or that particular film. That’s what I was talking about, not a duration internal to a subject, but ultimately a film’s own, singular temporality, which would at least fall under the second level, which is the rhythmic level, and the qualitative level.

Deleuze: Did you mean to say, in fact, that it was beyond rhythm?

Carasco: Yes, because if I take, well, to put it crudely… there are films that you feel have something to do with time, the films of certain directors… we feel, quite clearly, I don’t know, the specific temporality of Murnau, for example, or Duras, in all of her films… or even Welles. These are big examples. Or Resnais. So, it has something to do with what you call the time-image. But for me, it’s the overall time-image of the film that I was talking about. Okay?

Deleuze: The time-image…?

Carasco: Of the film as a whole, that is the film as a time-image, and therefore the duration of a film.

Deleuze: The time-image either refers to chronological time… [Inaudible remarks] Well, you said that there’s another time-image which would consist in a non-chronological time and would relate to the whole film, or a part of the film. And that’s what we’re talking about… [Inaudible remarks] So, lastly, the rhythm…

Carasco: The rhythm? This is a time-rhythm, you see… And it’s not a metric rhythm, of course. It’s not a mathematical pattern, right? Rhythm is on the side of the time-image.

Deleuze: So, you want this obtuse time to be beyond the movement-image and beyond the time-image… [Inaudible remarks] is that right?

Richard Pinhas: Before moving on to the next point… I didn’t understand the relation between time, duration and rhythm…

Carasco: It’s not easy.

Pinhas: No… but can you explain the relation between the three? I don’t understand.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Pinhas: No, no… okay, forget about that, but speaking about… [Inaudible remarks]Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]… she puts rhythm on the side of non-chronological time.

Pinhas: I get that. But what, what… on the side of non-chronological time, namely pure duration, pure cinematic duration, a time specific to cinema… what are the relations and what are the definitions of time, duration and rhythm?

Deleuze: In my view, it doesn’t matter to her.

Pinhas: Really?

Deleuze: It doesn’t matter to Raymonde Carasco, because she’s made a… it’s a whole other problem… [Inaudible remarks] that’s another problem altogether…

Carasco: No, it does matter to me in the sense – I’m answering, I’m answering you, and I think we agree on that – it does matter to me. That is, it’s obvious that for me, the concept of rhythm is absolutely fundamental and central to thinking about, let’s say, what I call a poetics of cinema. Because my project isn’t about logic. I’m not trained to construct a logic of cinema. It’s not my job. But what I’m looking for is something more specific. What I’m working on isn’t so new. What I call poetics is perhaps a term that needs to be revised, that is to say a poiein, how it’s made, how a film is made. So, in terms of poetics, it seems to me that the concept of rhythm is absolutely central, fundamental, and that we need to think about it.

So, if you ask me, What does cinematic rhythm mean to you? I have to tell you, I don’t have… I haven’t produced a concept of cinematic rhythm, I’m still looking for one, but it’s obviously a very, very strong focus in my questioning, this question of rhythm. So, for me, it’s much more a question than a ready-made concept. Besides, it implies a lot of things, like analogies with music, poetic rhythm in the ordinary sense of the word, and cinematographic rhythm, so it’s a very complex thing.

Lucien Gouty: You don’t think it corresponds to style?

Carasco: Yes, but not entirely. I think the notion of style is insufficient, it’s too narrow. Well, maybe that’s another question, I don’t know if we should talk about that now.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: That’s why I’m answering that it’s not at all obvious to me. Rhythm… is obviously an important question. And it has to be defined and constructed, it’s a concept to be constructed, depending on the filmmaker in question, and there are typologies of rhythms that need to be defined.

Deleuze: So, let’s go back to… [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Okay. The question I asked myself is… I had asked myself this question, I had established this distinction based on something that I find useful in Duras – a short text at the beginning of the introduction to India Song [1975], one of the rare, somewhat theoretical texts by Duras on cinema – in which she says that in the end, writing a script, a shot breakdown, is something she does for the technicians… the breakdown, shot by shot, but it’s not… it’s not that… I don’t need it. I do it to give it to the crew members, the director of photography, the cameraman and so on…

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks] … and to the funding commission!

Carasco: [Inaudible remarks] … right, and she says that, ultimately, there is an idea of the film. Actually, she doesn’t say an idea, she says that there is an overall image of the film, a mental image of the film, even before she starts writing, even before shooting and so on, and that’s what interested me. And I said to myself that in this mental image of the film – so should we call it the idea of the film, as Eisenstein says, are they the same thing? I don’t know – but in the mental image of the film, you have a view of the film in its totality before you’ve even begun to write a word, and you start writing when you have this view. And then, precisely to establish… so I would say that it’s a kind of view, and that’s what interests me. So, is this a third level, beneath the movement-image… sorry, the duration-image, if you want to call it that… is it a third level? Or is it still and continually the duration-image? Well, that’s a question I’d like to ask you. And one that I ask myself too. It’s not simply… [inaudible remarks]

So, obviously, in this sense, is it from this mental image, this view that she herself says is an open totality? And on this point we agree. She takes the image of a river flowing into the sea, and then the sea flows into who-knows-where, and that would be the world, so the film as an open totality… It seems to me that it’s from this, from the idea of the film, from the overall mental vision of the film, perhaps the unconscious idea – I don’t know if it’s the same thing – well, from this, it seems to me that this is how the rhythm of a given film unfolds. The fact that we’re going to take, I don’t know, a rhythmic alternation of two sequence shots, and then time-image, and then on the other hand, a briefer, sharper montage of two still shots, for example, as in the early Resnais films, or the fact that Duras will make her film with such and such a rhythm, it’s in a way completely secondary, and it’s already decided, virtually contained in the idea of the film. What controls the idea, the rhythm of a film, what I call the rhythm of a film, is also the fact that here we’ll do a close-up, and there a long shot. You don’t think: If I do a close-up, I’ll also do a long shot. In the idea of the film, everything is already there. So that’s it, that’s what seems to me to be the point we should be reflecting on.

Deleuze: No, it’s not the same thing. You said it yourself, there’s a global image. My question was: Can we give a positive character to this beyond of the movement-image? In a sense that you’ve just defined as non-global, non-globalizable, since, as Barthes says, it’s within the fragment and can only occur in the still, namely the mental image…

Carasco: Ah, no, no, no, not at all…

Deleuze: My question, then, is the obtuse meaning… [Inaudible remarks] beyond the movement of time, is there still a… [Inaudible remarks] that is, … [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: Or else it’s a kind of contracted duration, a contracted duration of the film, from which the film, and the rhythm of the film, will be able to unfold. Well, then, this is where I say I’m going back on what I wrote before. I’m now speaking about a contracted time, a contracted duration, but it’s still time and it’s still duration. So, how can I think outside of it, if it’s… well, if I call this an initial image of the film, global but initial? What I think now, rather… and this would be in line with Barthes, because Barthes speaks about reading, you know, reading the still, and his theory is a theory of the reading of the still. And he says that, in the end, in this reading, you always have the obvious meaning. The symbolic and obvious meaning, the communication, is always there, and the obtuse meaning doesn’t affect this meaning at all. And in a way, that’s it, these two meanings… they’re in a palimpsest relation, he says, and basically… in a palimpsest, at the level of… one which is real and not textual nor analogical, like… and it seems that it’s a meaning that has to be scraped off. There’s a layer, you scrape away, and then underneath another text appears, a double text. But then there’s a first one you have to scrape off, and the other one is underneath, okay. Whereas Barthes says…

Deleuze: That’s what drove Saussure crazy.

Carasco: Well, Barthes says that the first and second can be inverted, in his still and his reading of the still. In other words, there aren’t two separate meanings, they co-exist, and he says it’s a very twisted arrangement that implies a temporality of signification.

So, I’m about to leave Barthes, and I don’t know, maybe I’ll say something even more… [Inaudible remarks] Anyway, I came across a Blanchot text in The Infinite Conversation, “Speaking is not Seeing” [9], and there’s a moment where Blanchot gives a definition of the image. So he begins with the dream, with the fascination we can have with the image of a dream, and then, at one point, in a moment of dialogue, he speaks about the image, and says that there is always a duplicity in the image, and that higher, as he says, further than this duplicity, there is what he calls the turning point, the torsion – turning in the active sense – from which the duplicity of the image could unfold. So, I say to myself, if there is a turning and a torsion that is originary, that would in some way come before the image, before the duplicity of the image and before language, well… this turning nonetheless involves time. There can be no turning if there is no time. So that’s why I go back on my text. Is it…?

Deleuze: The answer to Barthes’ final question is very coherent… [Inaudible remarks] So, thank you very much. Do you have anything to add?

Carasco: No.

Deleuze: [Inaudible remarks]

Carasco: I hope I haven’t been too long or too obscure. What do you think?

Deleuze: No, no, it was very clear… What time is it?

Student: 11:30.

Deleuze: 11:30! But that means it’s break time! I think the points Raymonde Carasco made are very clear. So it’s not at all my intention to criticize. I find it very helpful and I needed her intervention to tell you how I myself see these three problems. I don’t see how I can make my own point of view chime with that of Raymonde Carasco but it doesn’t matter, we can maintain different points of view.

First point of view, I’d say, then, let’s not beat around the bush: What is this business, what do I retain – Raymonde said very well what she herself retained of this obtuse meaning – well, what do I… How do I feel about it, in the way Barthes’ text expresses the question? There’s one thing that troubles me. I stand by what I said, I stand by it. I still don’t understand it, because, basically, it tells me nothing, whereas other texts by Barthes tell me a lot.

But there’s one thing that strikes me. It’s in the two main examples he gives – I’ve already mentioned them – he tells us: It’s very difficult to say what I’d like to tell you, but here it is, the old lady who proclaims her sorrow in the image or in the special still, you’ll remember, where her bonnet has fallen almost on her eyebrows, where there’s the line of the bonnet, the eyebrows, the mouth, the eyelids, the mouth, in a special organization that forms part of the series of stills of this weeping woman. Well, there’s this one where the obtuse meaning is embodied, and what does he tell us? He tells us: You see, she looks as though she’s in disguise. In the others, she doesn’t look disguised. In the others, it’s just a woman crying. To translate this, we can say it’s an attitude, an attitude, or it’s a posture. Her whole body is engaged in her grief, it’s a bodily attitude.

But then, according to Barthes, a still of an image appears that is, for the moment let’s say, unusual, and which will disappear, giving the impression that she is disguised. You remember, “All these features (the absurdly low kerchief, the old woman, the squinting eyelids, the fish) have as a vague reference a somewhat low language, the language of a rather pathetic disguise. United with the noble grief of the obvious meaning” – you see, she bears a noble grief – “they form a dialogism so tenuous that there is no guarantee of its intentionality”.[10] Very fleeting. You get the impression that she is disguised. And he senses how dangerous what he’s saying is, because he then adds: above all, it’s not at all a “parody”. It’s not as if all of a sudden there’s a parody of grief, a kind of imitation. It’s not a parody. Nor is it that she doesn’t feel. Nor is it that she no longer experiences grief. She feels grief fully, but we have the bizarre impression that she is disguised, a disguise that perhaps only profound grief can produce.

The other example, which, as Raymonde Carasco was right to say, is Barthes’s essential example, because the other example he gives us leaves us even more confused… the example he gives, as I said very quickly last time, is during the coronation of Ivan the Terrible, when in Ivan the Terrible [1945], there’s the coronation scene, a magnificent scene, with the rain of gold that the two courtiers pour on the head, on the crown, and which trickles down onto Ivan the Terrible’s cloak. He says: Look at the courtiers, here they are. And it’s in a text where he says, I’m going to… I’m going to try to tell you what the third meaning, that is, the obtuse meaning, is. “I cannot give it a name, but I can clearly see the features – the signifying accidents of which this heretofore incomplete sign is composed.” – Listen carefully – “There is a certain density of the courtiers’ makeup, in one case thick” – since there are two of them, here in a still, the makeup of one of the courtiers, thick makeup – “thick and emphatic” – in the picture of the courtiers – “in the other smooth and distinguished; there is the stupid nose on one and the delicate line of the eyelids on the other, his dull blond hair, his wan complexion, the affected smoothness of his hairstyle which suggests a wig, the connection with chalky skin tints, with rice powder”.[11]

It’s all the more bizarre to tell us this at a ceremony. And he tells us, in the overall ceremony of the Tsar’s coronation, there is one still or a number of stills that are singular. How does he define them? The characters are not only disguised by virtue of the ceremony – that would be part of the obvious meaning – they look strangely disguised in another manner. They are disguised in disguise. They’re redisguised on top of the first disguise, that is, on top of the ceremonial costume. And this too is no parody. And it’s very dangerous. He’s in the process of… – and this is what interests me in the text – he’s touching on a bizarre notion of mask in relation to the two courtiers, their faces are a kind of mask.

In the case of the old woman, we also have a face-mask, a mask, a disguise. But what kind of mask? What kind of disguise? Generally speaking, masking or disguising oneself always means masking oneself as something else, or disguising oneself with something else. And this would indeed be the case with the courtiers in relation to the ceremony. They put on their ceremonial garb, just as the Tsar himself put on his ceremonial clothes. He is disguised as something other than himself. And when my face becomes a mask, the mask is something other than the face. So that’s what I’d call the “ordinary” situation. But isn’t Barthes… sensitive as he is, isn’t his sensibility drawing out something of a different order? And isn’t he saying something like: Careful! Sometimes we disguise ourselves as ourselves, or sometimes we mask ourselves with our selves. I can disguise myself with my own clothes, my everyday clothes. My face can mask itself with itself without needing to borrow another face.

And I sometimes have the impression that certain faces become their own mask. When a face becomes its own mask, it’s completely different from when a face dons a mask. When a body disguises itself as itself, it’s a completely different matter. This is not at all the case with a masked ball. In a masked ball, well, I buy a mask, I buy a costume, and I mask myself, and I disguise myself as another, as something else, I mask myself as something else. Here, I mask myself with my own face, I disguise myself with my own clothes. In other words, I mask and disguise myself as myself, as myself in the sense of “with” myself. My face has become its own mask. My body has become its own disguise.

Ultimately, this is an incomprehensible notion, or perhaps it refers only to furtive impressions. For example, I see someone, and I say to myself: What’s odd about them today? And I can’t answer because, in a sense, I can only answer one thing: Nothing! There’s nothing odd about them. In other words, there’s nothing that isn’t them. And yet it’s as if their face has become their mask. Perhaps death has this effect? To speak of cheerful matters, we always talk about a death mask. If Barthes didn’t use this example, I think it’s because he detested death. Because it seems to me that it’s death that helps us most to understand this. When death seizes the body, the face becomes its own mask. Death is what disguises us as ourselves. The recently deceased body is disguised as itself. The mask of death is the face itself as it secretes its own mask.

So here I see things differently, and this would be my first difference, with regard to the first problem we confronted. I would say, if I can give a sense to this expression “obtuse meaning”, for me it’s that the obtuse meaning would designate the moment when I am neither myself nor another, that is, when I am neither naked nor disguised, but when my nudity disguises me as myself, if you understand the “as” correctly. I am disguised as myself, exactly as I said last time at the end of my lesson, Kerouac, at the end of his life, feeling he was dying, said: “I’m tired, I’m sick of myself”. I’m the one who’s disguising myself as myself! I’m the one who’s sick of myself. It’s this woman’s grief that disguises her as a grieving woman. It’s the opposite of an imitation of grief. It’s the opposite of a parody of grief. The courtiers are disguised as themselves, that is, it’s their ceremonial costume that induces a second disguise on top of the disguise constituted by the ceremonial costume. So, I don’t see anything else. I don’t see anything else. Therefore, this is very different from what Raymonde Carasco sees.

But what can I draw from this? I draw something that, for us, may bring us back to our problem, namely that the obtuse meaning thus defined would indeed constitute a limit. It would indeed be a limit. But a limit from what to what? It would be the imperceptible passage, the imperceptible passage from an attitude, grief, to its self-disguise, that is, its gestus. Or, if you prefer, it would be the imperceptible passage from the everyday attitude to the… not to the ceremony but to the ceremonialization of the attitude. It would be, in the words of an American sociologist, “the presentation of self in everyday life”.[12]

Let’s go back to Godard’s most basic example. A series of everyday attitudes tend towards a limit, their theatricalization. This is not at all like a passage from everyday attitude to theater. It’s not a passage from everyday life, from everyday attitude to theater. It’s a process of theatricalization of everyday life. It’s a process of theatricalization of everyday attitudes. So I’m right back at the heart of my problem. We will say that there’s a series when a sequence of attitudes – for example, the attitudes of the grieving woman – tends towards a limit: the theatricalization or ceremonialization of these attitudes. And the everyday attitudes are reflected in this limit. And there aren’t two terms – the everyday and the ceremonial – there’s a truly vectorized process of passage from one to the other, in other words, a theatricalization of the everyday attitude, a ceremonialization, a staging of the everyday attitude. So, it’s in no way a parody. I’d just like to state in advance, before we have a short break, the point I’m trying to make.

It’s this. A limit, a limit is, as you prefer, reached or exceeded. The succession of attitudes, what Barthes isolates in a still, is the limit in which the preceding succession of everyday attitudes of the woman overwhelmed by grief is reflected. And what is this limit? It’s that grief disguises her as herself, grief disguises her as herself.

If you follow me a little, I’m getting ahead of myself. But if this were the case, we’d have made a considerable achievement, namely that, in this process, there would necessarily be a passage from a before to an after. There would be a passage from a before to an after. I can’t explain this very well yet, but I’d like you to at least have a vague idea. In other words, a limit is reached or exceeded. There’s a before and an after. A limit is reached or exceeded. A sequence of everyday attitudes reaches or exceeds the limit of theatricalization, of ceremonialization. From that point on, there’s an arrow, a vector. There’s a before and an after. There’s a before and an after.

But you’ll tell me that this is just a commonplace. Oh, not at all. Not at all. Why not? Because it’s a serial before and after. It’s a serial before and after. What does that mean, a serial before and after? Above all, you mustn’t confuse them with the before and after of chronological time. It’s fantastic what we’re doing here, if you follow what I’m saying. Well, kind of fantastic… I think it’s perfect, anyway. We’re tearing the before and after out of chronological time.

There is a before and an after according to chronological time. And what is this? I’d call it the course of time. The course of time is the determination of the before and after according to chronological time. But there’s also a completely different before and after. It’s the before and after not of the course of time, but of the series of time, and this before and after, this time, how are they defined? When a sequence is vectorized, that is, when it tends towards a limit, this is what defines the before and after.

Example: perhaps because it’s the most basic example, the staging of everyday life, the staging of everyday attitudes, in the sense that it gives us this limit. We pass, we pass, imperceptibly, from the attitudes to the gestus that… what does it do? That connects them? That connects them, but that connects them afterwards, once it has arisen, to the gestus that relinks them. There’s a serial before and after that mustn’t be confused with the chronological before and after. I’d say we’re already a long way from – we’ll get back to it, we’ve got to proceed very slowly here… because it would allow us to say something about the time-image that I hadn’t grasped last year, that I didn’t grasp – for the moment, we’re just at this point: the idea of the operation by which we disguise ourselves as ourselves, and in what way this operation propels us into a kind of vectorized time, of staging, of theatricalization, by which we move from attitudes to gestus. But we don’t pass from attitudes to gestus, without passing from a before to an after, but a before and an after that pertain to the series of time and no longer to the course of time. Well, we’ll have to… those who don’t understand yet shouldn’t be too worried.

I mean, again, I mean, it’s not like in [Jean] Renoir, where there is life and there is theater. I don’t mean that in Renoir this is insufficient. I mean that Renoir’s is a completely different problem. Here, this isn’t the problem at all, it’s not a question of life or theater. It’s not where one begins and the other ends. It’s not that at all. It’s the process of theatricalization that will relink attitudes once it has been reached. So there’s a serial before and after, which is not the same as the chronological before and after.

You might say, well, let’s assume this. Forget this business of the still for the moment, we’ll come back to that. But this is what we need, that’s what we need to specify. Where to capture it? How do we capture it? How do you capture it in cinema? I’m not concerned with the still at the moment, I’m not concerned with the still yet, I’m not concerned… I’ve dwelt on the obvious meaning, the obtuse meaning… obvious meaning, obtuse meaning… I can’t go any further with that. What interests me now is this passage, this serial passage which is not a chronological passage. How are we going to identify this passage this limit? How are we going to uncover this passage, or this limit? How are we going to redistribute the before and after? In other words, how are we going to redistribute the before and after, which once again amounts to saying: What does it mean to disguise oneself as oneself? [Recording interrupted] [1:48:03]

Part 3

… Well, I’ll tell you what it means to disguise oneself as oneself, or I’ll try to give you a preliminary answer. To make this as clear as possible, to disguise oneself and oneself means to fabulate.[13] It does not mean to lie. Let’s suppose that it means to fabulate, to create a legend, to be caught in the act. Caught in the act of what… lying? No. Being caught in the act: this would be the limit, the passage. Being caught in the act of theatricalization, being caught in the act of ceremonialization, being caught in the act of fabulation. So, this is what would define the moment before and the moment after. You might ask, is that so important? Is such a childish example sufficient? Is it really sufficient for us to distinguish a serial before and after? Well, perhaps it is.

I jump to a filmmaker who has nothing to do with all of this: the great Pierre Perrault, one of Quebec’s finest filmmakers. What does Pierre Perrault say? He makes a kind of cinema that he calls… he says, I don’t like the expression “direct cinema”. We’ll see why. We’ll see. We find ourselves thrown back into an almost unexpected type of problem, but we haven’t done it on purpose. I don’t like direct cinema, he says, I prefer to call what I do a “cinema of the lived”. But how does he define this cinema of the lived? Not as fiction, not as pre-established fiction. So, what does this mean? He will make a cinema of the lived. He’ll take his Canadians, his Quebecers, and then… But indeed, he began making reportage films. But very quickly he broke with reportage, no more reportage. And no doubt, right from the start, his reportages were something other than reportages.[14]

Why does he break with all fiction? He gives a very simple answer. He says, what interests me is when… [Recording interrupted] [1:41:00]

… character. Well, this is starting to become clear because it’s an odd idea. Our immediate reaction is, Well, what does it matter? What difference does it make whether the fiction comes from the character or from the filmmaker himself? And indeed, in a very curious dialogue that seems at cross purposes – but a dialogue is never entirely at cross purposes – French filmmaker René Allio and Quebec filmmaker Pierre Perrault talk about their problems, which they agree form a common problem. And Allio says to Perrault: I don’t know what you mean – you see, he’s not the only one… – I don’t know what you mean, I don’t see the difference between a fiction that I make as an author and in which I include authentic characters, and you, who want authentic, real-life characters, but want them to fictionalize themselves.[15]

And Allio goes so far as to say, why should a poor Native American’s fiction be better than mine? What interests Perrault is the moment when the Native American begins to make up a fiction. Whereas Allio replies, If I were to make a fiction, why should it be worse than the poor Native American’s? Why do you have to take a real character and push him to the point where he makes up a fiction? – you see, that’s the core of the problem we are dealing with here – And Perrault replies very kindly, but with typical Québécois politeness, You don’t understand anything, You don’t understand anything. You don’t see the difference between your own fiction and the Native American’s fiction, and you don’t even see the Native American’s fiction. And Allio says, No, I don’t understand, I don’t understand.

And Perrault says that when the Native American begins to make up a fiction, it’s in the name of what he calls a “fabulous memory”. You see, fabulation, fabulous, must be taken in the sense of the fabulation function. It’s in the name of a fabulous memory, in other words, it’s in his relation with his own people. Why does the relation with the people involve fiction, this time, the fiction of the poor Native American? In other words, Perrault develops a function, a formidable idea: fabulation as a function of the poor, fabulation as a function of the oppressed, legend as a function of the oppressed.

And this is quite normal, since he’s crushed by history. Crushed by history, he unleashes the fabulation function. What is fabulation? It’s an appeal to his people. While the filmmaker’s function, Perrault says, is to make people see the filmmaker’s function… by nature, the filmmaker is cultured. Not that much, in fact… but however little he may be, he is still cultured. He’s a cultivated person. In other words, says Perrault – and here Perrault’s words are splendid – he speaks on behalf of a colonizing people. By nature, the filmmaker speaks on behalf of a colonizing people. And Perrault says, Even I, a poor Quebecer, if I invent a fiction, you’ll see that the dominant ideas, that is, the ideas of the colonizing people, will always creep in.

So the filmmaker, even if he’s a native of the country, even if he’s a Quebecer, has to create – and this really is creation – by bringing the real characters, the poor, the oppressed, not to recount their truth, but to create a legend, fabulous memory. Why is this? Because, being oppressed, they have lost the people. The people have disappeared, the people are missing. To invent a people who nonetheless exist, says Perrault, to invent a people who nonetheless exist. This is true for the Palestinians, it’s true for the Kanaks, and today it’s also true for Quebecers.

This people exists, yes, but it exists outside history, it exists outside experience. So where does it exist? It exists insofar as it has to be invented, both at the same time. How will it be invented? Through fabulous memory. There is no history here, since history is always that of the colonizer. Fabulous memory, that is, what becomes essential is that there be no prior fiction, but that we pass, imperceptibly, from the everyday character’s lived experience of oppression to the fabulation function. We pass from the poor native American to his fiction making, to his activity of making fiction, of making a legend, and it’s in his activity of making a legend that the relinkage with the people takes place, the relinking with their people in a situation where there has never been any prior linking, because theirs was a crushed people.

If this is what Perrault is saying, he’s bringing something very important to our problem. You see, this passage where we are disguised as ourselves, in the same way, the character will make a fiction of themselves. They are not part of a prior fiction. Here, I’ll read you Perrault’s splendid text, the short exchange between Allio and Perrault. Allio: “Fiction… which consists in telling stories that one invents, makes just as much sense if it’s you who invents or if the one who invents is a real character in the film” – so, what’s the difference? – Perrault doesn’t say yes or no… – “If the Native American tells a legend, he finds himself in a state of making legends, caught in the act of making up legends. But the legend, proposed as an account of what happened, does not separate itself from lived experience.”

Under the name “cinema of the lived”, Perrault lays claim to a mixture of lived experience and fiction. But it’s not a question of mixing lived experience and fiction, as if there were both lived experience and fiction. It’s a mix such that, on the contrary, the character will pass from a vectorization of their lived experience to the fabulation function, their fabulous memory, through which they invent a relation with their people by finding it again. And here we have the figure we were discussing before. There’s a before and an after, and they meet again. If the Native American recounts a legend… let’s first imagine them there, without recounting a legend. Their life drags along. And then, little by little, and this is a very subtle movement in Perrault’s cinema, the characters start recounting legends to each other. There’s a before and an after, we’ve moved from one element to another. There’s been a fiction-making that’s the equivalent of what earlier on I called theatricalization. A series of lived attitudes is reflected in an act of fiction-making, in a fabulation function. There’s a before and an after, but this before and after are not chronological. They don’t refer to the course of time, they’re serial, they refer to a time series.[16]

A time series has nothing to do with the course of time. The time series is not chronological, and yet – and this is the pseudo-paradox that is so important to me but that I missed last year – and yet there’s a before and an after, a before and an after of the series, without this before and after having to be understood chronologically.

Let’s have a break. Let’s have a break. So, now I really need, could you be so kind… are there three people her incapable of lying? You, for example? You can go… you can go for a coffee… over there, you go for a coffee but at the gallop because we don’t have much time. So run, okay? Run very fast. Go get your coffee. And if the machine is out of order, you don’t stop, you go straight to the secretary’s office. And then if you can be so kind, if Zouzi is there, you know who Zouzi is, right? Give him… but I need someone else, I’d like someone else to go with you, yes, if you could be so kind… [Recording interrupted] [2:01:57]

So, the… no it’s not a vacation, the mid-term meditation runs from the 9th to the 25th. That’s a fortnight, two weeks? Okay? From the 9th to the 25th, so this is our last session. So we need to find a point that’s easy to remember, which is going to be hard. So we’re going to shorten this last session. It’s a… what day is the 25th ?

Student: It’s a Monday.

Deleuze: Yes, it’s a Monday! Wait… what day is it? Do I read… yes, maybe it’s the 27th. Okay, so if Monday is the 25th, then we’re back on the 26th, the 26th. Okay…

Yes, I insist, because I think it’s important, at least it is for me. You see, we’re right in the middle of the first question, aren’t we? For the moment, we’ve completely dropped the whole thing about the still. But what interests me is this… this kind of cinema that has been badly defined as direct…

Georges Comtesse: I’d like to ask you a question.

Deleuze: Yes… sorry, we have to close the door.

Comtesse: Based on what Raymonde Carasco said about what in cinema could – but which wasn’t clearly specified – what could be beyond the time-image and the movement-image, I’d simply like to take something that doesn’t necessarily pertain to cinema but which could be translated, which has perhaps been translated into cinema. I’d simply like to talk about the greatest defender, the most obstinate defender, or rather, the most relentless guardian of the order of time, not its mode, its course, but its order of series. I’d like to talk about the obsessive neurotic, and above all, when the obsessive neurotic… when the fiercest guardian of the order of time, is traversed by certain events that are literally uncontrollable. For example, the event of extreme tension, of a conflict that rages within them, of agitation, fever, disorder, vertigo, vertiginous disorder, that is, this event or this series of events where they are literally confronted with the most obscure stranger within themselves, when they are besieged, assaulted, even attacked by the stranger within.

It seems to me that this series of events can no longer, literally, be reinscribed in the order of time of which they are the defender. If they do this, it will necessarily… they will almost always do it, but if they do, it will be in a way that literally defines obsessional imposture. If, within this imposture, they begin to elaborate a philosophical theory of time in order to justify the order of time, or to find a time, or to imagine that there is a time before the stranger, that the stranger is a function of time, then it’s no longer simply obsessive imposture we’re dealing with. In terms of their philosophical theory, it will be imposture as fabulation. That’s all I have to say.

Deleuze: If I understand correctly, it’s for me… I’m the one doing all this. No, it’s not me? I thought I recognized myself!

Comtesse: It’s not something that’s necessarily assignable. I can talk about people I know, that’s all. That’s all there is to it…

Deleuze: Oh, yes!

Comtesse: Far be it from me to maliciously include you in this!

Deleuze: No, no, no, but… in any case, I couldn’t be part of that, since I’m not an obsessive neurotic. And so that puts me out of the category of imposture and imposture as fabulation, since I’m not an obsessive neurotic. So maybe it’s Raymonde… Well, I prefer to take a more neutral view of what you’re saying, the possibility that we could develop, as has been done in a very interesting way, psychiatric forms of temporality based on all this. But in fact, from what you’re saying, you wouldn’t be so much in favor of that. Well, listen, I’m still unsure. I feel it’s better not to… it’s better to move on. I take your point but indeed, as you say, you’ve got to let it, to let it… okay.