March 26, 1985

So, we saw this slightly unusual author among linguists, Gustave Guillaume, offering us an idea. And you already sense that it is complicated because of this idea: Is it in linguistics the maintenance of a certain tradition that linguists usually rejected? Is it, on the contrary, a new way of posing linguistic problems? Or is it both? It may well be that they are both at once. In any case, it’s a very particular point of view consisting in telling us that, in a certain way, there is a pre-linguistic material. … That’s why I made the connection with Hjelmslev. However pure a linguist he is, when Hjelmslev tells us, “there is form and substance, in language, substance being a formed matter”, but adds that, henceforth, there is of course in any mode at, one that’s very complicated, an unformed non-linguistic matter that language presupposes, an unformed non-linguistic matter, then I am saying that Hjelmslev remains very discreet on this matter. It is like a linguistic presupposition, whereas Gustave Guillaume is much less discreet. He tells us that there is “a signified of power”. And this “signified of power” is truly pre-linguistic material.

Seminar Introduction

As he starts the fourth year of his reflections on relations between cinema and philosophy, Deleuze explains that the method of thought has two aspects, temporal and spatial, presupposing an implicit image of thought, one that is variable, with history. He proposes the chronotope, as space-time, as the implicit image of thought, one riddled with philosophical cries, and that the problematic of this fourth seminar on cinema will be precisely the theme of “what is philosophy?’, undertaken from the perspective of this encounter between the image of thought and the cinematographic image.

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, 1925

Deleuze announces that the class will first complete the transition from the linguistic and semio-critical review and then shift to discussion of the intersection between visual and sound elements. He thus continues with the linguistics of Gustave Guillaume and Hjelmslev, their different concepts corresponding to “processes of thought-movement”, with verbs producing processes of “chrono-genesis”. After arguing that Guillaume’s system of differential-inclusive oppositions had significant subsequent consequences for semiology and post-structuralist linguistics, Deleuze presents his own doubts about three key points of semiology’s take on cinema, arguing for “pure semiotics” operating with images, signs, and non-language processes determining these images and signs, creating something “utterable” (énoncable). This “anti-semiological semiotics” is one developing a Bergsonian process of thought-movement on which instantaneous views are obtained. Deleuze then shifts to the second phase, to study what a properly cinematographic image is and what its relation is with non-language processes both in silent and sound films, also announcing possible interventions after the Easter break (e.g., Giorgio Passerone, Eric Alliez). He then forecasts development in coming session of the cinematographic statement’s three key stages (silent cinema with reference to Soviet, American, and French examples; spoken cinema part 1, pre-World War II; and post-War cinema). He starts here with the silent era’s successive visual facets (e.g., images and intertitles), and concludes with Benveniste’s distinction of story plane (corresponding to the historical visual image) and discourse plane (non-historical visual image), understood in terms of the passage from readable and visible silent cinema into the intertwining of these within the phases of spoken cinema. [Much of the later section’s development corresponds to The Time-Image, chapter 9.]

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Cinema and Thought, 1984-1985

Lecture 17, 26 March 1985 (Cinema Course 83)

Transcription: La voix de Deleuze, John Stetter, relecture : Stephanie Lemoine (Part 1), Mélanie Pétrémont (Part 2) and Mélanie Petrémont (Part 3); additional revisions to the transcription and time stamp, Charles J. Stivale

English Translation: Graeme Thomson & Silvia Maglioni

Part 1

[Here Deleuze lists the main points to address in order to continue the seminar in the light of certain more or less urgent questions raised by participants]

… because I find it a bit grotesque the way the question of what it means “to be racist” is presented on TV. What would this be? And it comes down to things like: Would you be happy if your daughter married a white man, or a black man, or an Asian man? So, I don’t know, I have the feeling that one cannot pose the problem of racism exactly in these terms. On the other hand, I don’t know of any question that is satisfactorily posed, politically speaking, on the matter of, for example, equality… equality among people. How do you frame it? Considering how everyone replies: “Oh, I’m for equality”, even [Jean-Marie] Le Pen. But the question isn’t… it’s not whether one is for or against. Equality is like the existence of God, it depends entirely on what you mean by God. There’s no answer to the question: Do you believe in God? It all depends on what you refer to as God. Equality is a similar matter.

So, a good questionnaire, it seems to me, would consist in saying: You certainly believe, including Le Pen, you certainly believe in equality between people, that’s for sure. It’s better not to have a trial, then. But explain to us a little where you locate this equality between people? Well, I heard the Archbishop of Lyon give an interesting answer, which is the Church’s answer, very cautious, but very interesting: “For equality to exist, there must be dignity”. We don’t know what intelligence is either, it’s not up to us to decide, we don’t know what… and so on and so forth. But in any case, equality is a question of dignity. That’s an ecclesiastical notion, equality in terms of dignity.

Indeed, I think my dream would be to come up with a questionnaire that anti-racist movements could send to [Jacques] Chirac, and they would get very annoyed if he didn’t reply… they could send it to all types of politicians, because it strikes me that in many cases, the statement “We’re not racist” is considered sufficient. But it’s not true, it’s not sufficient. You have to say in what way you’re not racist. Again, it’s not… I don’t think it’s… – because I’d be very happy, if my daughter married a black man – but that’s not enough not to be racist, no, that’s not sufficient. It concerns something else.

But I’ll ask you right now if any of you would like us to devote part of… In my view, I would say, it’s pointless, given the nature of our work here, to denounce racism. I don’t think we should try to do it here. On the other hand, how can we effectively participate in the struggle against racism today? I have to admit that my ideas are quite poor, because apart from those shared by everyone else, those of all the anti-racist movements, I would only propose to put together a mass questionnaire, especially concerning, and addressed to, political parties.

Because… what makes this period… I don’t know what you think – now I only think in case the Socialists lose the election – me, I don’t believe that the reaction will be moderate. I don’t think, as some people do… Some people say, “Oh, the Socialists are moving towards the center” and all that… and also, “In some respects there won’t be any major changes.”[1]

I believe, on the contrary, that if they lose the elections, well, if they get trounced, there will be a very, very harsh reaction at all levels, at all levels. It won’t be moderate at all. I don’t know what you think about this. Having said that, it’s an important question regarding our individual attitudes. We are… If you think, as I do, that if you lose the election, the reaction will be very harsh, that implies a certain attitude, right now, towards the government, towards the Socialist government, which is not the same as that of those who think the reaction will be more hypocritical. Well, all that is… Actually, I don’t think it’s necessary, unless someone here thinks it’s necessary, to interrupt our work to talk about a question on which, as far as I know, we all share the same opinion. Any comments? Okay, there are no comments.

Second question on our agenda today: to smoke or not to smoke. Well, I’d like to point out that it may seem a small thing but it’s no healthier breathing in other people’s smoke than smoking yourself. Breathing other people’s smoke… it’s in the atmosphere, it’s terrible, terrible, even for smokers. That’s why I have only one solution to offer: you can smoke, but only one at a time. But then we’ll realize that it’s always the same person… so that’s no good either. So now that you’ve smoked a lot, I hope you’ll stop when you can’t take it anymore. If only there were rules, let’s say, there wouldn’t have to be only one, but we could go to fifteen. So, when fifteen people need to smoke at the same time, we’ll stop, and they can go and smoke in the courtyard, and we’ll just carry on, and then they’ll have to catch up as best they can. Fine… So, any of those solutions will work. But I’d like to point out that those who protest against the high density of smoke in this room are obviously not doing so out of malice or bad temper, but out of a physical panic reaction. So please respect them, because smokers are not respectable… okay?

Third point in the agenda: let’s work, let’s work a little… I can see you’re very uncomfortable down there, they have to leave you some space… So, again, I’d like our session today to be quite a gentle one… and it will consist in two parts: the end of the difficult part and the start of the easy part, which will continue after the vacations, as this is our last session before vacation.

[Music in the room: “Thus Spake Zarathustra” by Richard Strauss, Prologue to the film 2001 A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick]

But that’s not gentle music… You see? That’s exactly what I meant. Oh, dear! Whose is that? Is it yours?

Student: No, absolutely not!

Deleuze: Whose music is it?

Student: But it’s not bad!

Deleuze: Ah, yes, so… you prefer listening to that?

Student: No, no, I don’t prefer it, but in small doses… it’s actually quite pleasant.

Deleuze: Oh la-la! For me… it blocks my ideas… So, okay, I’d like you to… I don’t know, I’d be happy if… it’s not important, once again, that you understand everything, but I’d like you to become aware of certain problems that seem to me crucial with regard to the semiotic and the semiological question. I’m slowing down to try to help you understand.

So, we saw that this unusual linguist, Gustave Guillaume, proposed an idea. And you can already feel that it’s complicated, because this idea… does this idea imply maintaining a certain tradition in linguistics that linguists usually reject? Or is it, on the contrary, a new way of posing linguistic problems? Or is it both? It may very well be both. In any case, his particular point of view consisted in telling us that, in a way, there exists a pre-linguistic matter. There is a pre-linguistic matter. That’s why I made the connection with [Louis] Hjelmslev. When Hjelmslev, despite being a pure linguist, tells us that here is form and substance in language, there is form and substance… substance being a formed matter… but then he adds that, consequently, there is indeed in some way, in a very complicated way, a kind of matter that is non-linguistic, but which is presupposed by language, a non-linguistically formed matter. Here I would say that Hjelmslev remains very discreet about this matter. It’s like a presupposition of linguistics. Gustave Guillaume, on the other hand, is much less discreet. There is, he tells us, a “signified of potentiality”, and this “signified of potentiality”, is truly a pre-linguistic matter.

Before we get to this point, you can immediately guess the reaction of other linguists, who will say: Guillaume may be an excellent linguist, but on this point, he brings back all the old metaphysics, a precondition for language that would be like a non-linguistically formed matter, like a pre-linguistic matter, and which he calls the “signified of potentiality”. As we’ve seen, he also sometimes called it a “psyche of potentiality”, and in what form did he present it? He presented it in the form of a thought-movement, or a movement of thought. And perhaps, don’t get me wrong, perhaps such movement, such a signified of potentiality, doesn’t exist independently of language. That’s possible. It exists only through and in language. But even if it exists only through and in language, it exists as something presupposed by language, presupposed by right, ideally presupposed by language.

This signified of potentiality is a movement, and it corresponds to the meaning… to the meaning of a linguistic unit. Hence the fundamental idea that a linguistic unit has only one single meaning, whatever its use in language. So, in any case, we’re advanced enough to know that there’s no point in looking for a term or a concept that would convey this single meaning for a linguistic unit. Once again, it’s a movement, a movement of thought. And in this sense, every linguistic unit… or rather, a linguistic unit has this signified of potentiality for meaning. But according to its uses in language, it will operate with regard to this meaning or to this movement through cuts, and each use will correspond to a cut of this movement or a particular aim, he sometimes says, a particular aim with regard to this movement.

For example, as we’ve seen, the article “a”, the indefinite article “a” or “an”. It has only one signified of potentiality, only one meaning. It’s the movement of particularization. The indefinite article particularizes. It’s the movement of particularization. You see, the indefinite article is a sign, it refers to a signified of potentiality that constitutes its meaning, the movement of particularization. But the uses of the sign of the indefinite article in language will each be, or each time will give to the signs, to the article, a particular aim with regard to its meaning, that is, with regard to the movement of particularization, or they will constitute a particular point of view regarding the movement of particularization.

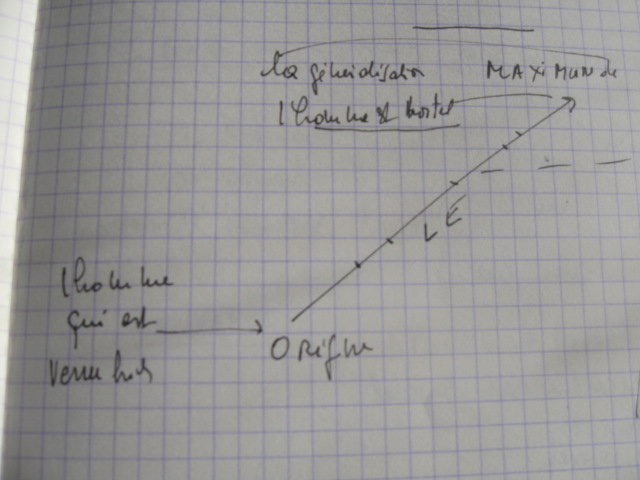

What might this be? The movement of particularization, we might as well say, it’s the movement by which something, a something, tears itself away from a background. For instance, a wolf appears… a wolf or an Indian appears. It’s this movement, and Guillaume makes a very fine analysis of the relation we’re forming here, and the indefinite article will extract something from the background. But it all depends. If I grant myself the movement of particularization as the signifier of potentiality, well, everything depends on what level you put it. It will always be “a”. The signified of potentiality is this movement of particularization… But I can determine a use for the indefinite article that I will call close to the origin. Close to the origin means that it’s close to what is general, since the movement of particularization is what goes from the general to the particular, close to the general. I can put it at the end, very close to extreme particularity… There, a man is mortal. That is, a man, whoever he may be, is mortal. Or a man has come. This is close to the maximum of particularization.

You see, I’d have to distinguish between three terms: the signified of potentiality is the thought-movement or the movement of thought, the pre-linguistic movement or non-linguistically formed movement that constitutes meaning, in this case, the movement of particularization. The sign is “a” in relation to its different occurrences in language. It is at every level of the possible cuts of the movement of particularization, namely the movement from the general to the particular. Thus, each position corresponds to a value of the sign, of the sign “a”. Insofar as it aims at the movement of particularization, at the signified of potentiality, we’ll say that the sign is charged with a signified of effect… insofar as it aims at the movement of thought, which is to say, at the signified of potentiality, it is charged with a signified of effect which, at that point, is attached to such and such a point of view. “A man is mortal” will be defined by and in relation to a certain signified of effect, and this signified of effect will not be the same in “a man has come”, whereas the signified of potentiality will be the same. Is that clear? You’ll see, I’m going slowly, because the consequences, when we get to consequences, they seem to me to be enormous for linguistics, as well as for philosophy.

But then, as I was saying, with the article “the”, you see, it’s the same thing. Let’s go back to the definite article “the”. The definite article, its signified of potentiality, or the thought-movement that constitutes its meaning, is different. It is generalization, that is, the movement from the particular to the general. So, it starts with the particular and rises to the general. But it’s the same thing. The definite article [le] has only one signified of potentiality.[2] In each of its uses in language, it operates a cut or a point of view with regard to the movement of generalization, that is, to the signified of potentiality. By the same measure, in each of its positions – it has positions, that’s the important term in Guillaume’s work, it has positions that it takes with regard to the movement that constitutes the signified of potentiality – insofar as it is apprehended in such and such a position, it has a signified of effect.

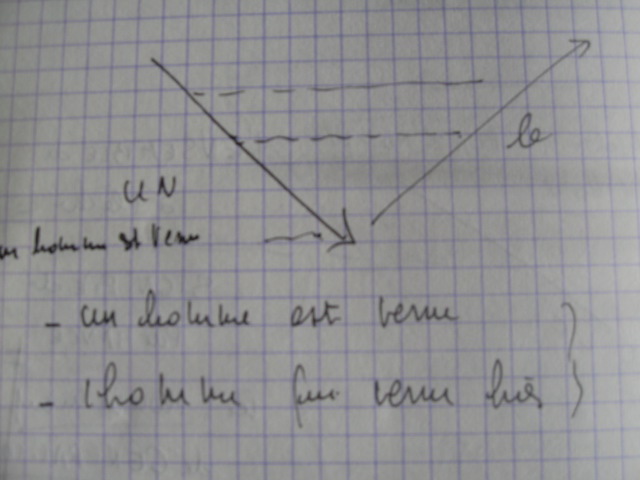

So, closest to the origin of the movement of generalization, namely closest to the particular, I have something like “l’homme qui est venu” [the man who came]… When I say “l’homme qui est venu hier” [the man who came yesterday], for example… in terms of the destination, namely of the maximum generality, I have a formula like “l’homme est mortel” [man is mortal]. You see, it’s always my three points: the pre-linguistic signified of potentiality, the linguistic unit that takes positions with regard to the movement implied in the signified of potentiality, the signified of effect that corresponds to each position.

So, I could always establish correspondences, and Guillaume establishes correspondences between my two series. For example, if I put together “un homme est venu” and “l’homme qui est venu hier”, there’s a match. Or if I put together “un homme est mortel” and “l’homme est mortel”. This comparison is perfectly valid, except that these are two positions – one of the indefinite article, the other of the definite article – these are two comparable positions, but two positions taken from two completely different movements, and which are in this case even two opposing movements: the movement of particularization and the movement of generalization. So that in one case, “un homme est venu”, the “un” will be a position – how shall I put it? – of the extremity of the indefinite article, while “l’homme qui est venu” will be a position of origin of the definite article. Why is this? Because they’re not taken from the same movement.

The same operation… and this is what makes Guillaume’s work so fascinating – and I’m not pretending to give a lecture on this, I’m just mentioning it very quickly – what makes Guillaume’s work so fascinating is that he will perform the same operation I’ve just summarized regarding the article, he will perform the same operation on the noun, which will lead him to… the distinctions multiply, it’s extremely precise, but it’s very amusing at the same time. Basically, he will say: we have two articles corresponding to two movements, definite and indefinite. As for nouns, he will distinguish three terms that also refer to the signified of potentiality, meaning to movements: the noun, the adjective and the adverb – which are for him the three fundamental forms of the noun.

It’s all very original, it’s a classification… and as you know, I really like classifications, I take great pleasure in… So, I’ll leave it at that, because we could have covered this another year, it would have taken us a whole term to go through it all. Guillaume is also interested in verbs, and this interest me for reasons we’ll look at in a minute…. I’m sure it hasn’t escaped you that his entire analysis refers to… – and it’s not by chance that I chose to refer to him – his entire analysis of the article refers to a signified of potentiality that presents itself in terms of movement of thought, a thought-movement.

So, I’d say, well, if we take a word that is useful here, “procedure” or “process”, in the case of the article the signified of potentiality is a process, a process of movement, whereas… I’ll leave aside his analysis of the noun. There’s a text, one of Guillaume’s most difficult texts, and also one of his finest ones, on verbs. If you’re interested in reading it, you can try to find it in the library – it’s called Époques et niveaux temporels dans le système de la conjugaison française… and this is where it gets tricky. It’s in Cahiers de Linguistique Structurale, number 4 [1955], Laval University, Canada. But as far as I remember, they don’t even have it at the National Library… no, they don’t even have it there. What to do? You could get someone to send it to you, as I did, someone sent me a photocopy… anyway, as I was telling you, Edmond Ortigues’ book on this subject, Le discours et le symbole, published by Aubier [1962], is a very remarkable book, and he devotes a whole chapter, chapter 6, to the conjugation of verbs according to Guillaume.

And he is… and, well, maybe he’s right, I don’t see it quite the way he does, but… Basically, as I’ve simplified a lot, it doesn’t matter. I just want you to remember, and please correct me if you read it, what I was saying about Ortigues. Well, I’d like you to remember… what interests me in the case of the verb is that it operates what he calls a chronogenesis, that is to say, the time that belongs to the signified of potentiality of the verb… it seems to me, it is a process of temporalization, a process of temporalization… [Interruption of the recording, 35:51]

… it’s the signified of potentiality of the verb, it can’t yet give us the tenses of a verb, since it’s a question of producing the genesis of the tenses. What are the verb tenses? They are signifieds of effects, they are the values taken on by the verbal linguistic sign, when it has an aim or when it takes a position with regard to the movement of temporalization. In other words, we need a chronogenesis, a chronogenesis of tenses. This chronogenesis cannot presuppose tenses. So, what will be the tool… what will be the means of chronogenesis? It will be the modes, and again, an extremely odd organization of modes.

What is the great movement to which the verb refers? Just as we were looking for the movements of the article, and his answer was that the article refers sometimes to the movement of particularization, sometimes to the movement of generalization, as a signifier of potentiality or thought-movement. Here, he invents a number of notions… the verb sometimes refers to a process he calls incidence, sometimes to a process he calls decadence. What is incidence? It implies that every verb marks a tension, every verb has a tension immanent to it. This is the notion of tension. Incidence is the occurrence of tension, the exertion of tension on matter. And decadence is the opposite, namely it’s accomplished tension, extenuated or exhausted tension, on which at that point we have an external point of view. Exhausted tension is called process of decadence. And this is the first stage of chronogenesis.

Incidence: “to sing” in the infinitive, the infinitive. I’m simplifying enormously here, enormously, my only wish is that rather than discussing this, you retain an impression. The infinitive expresses the internal tension of the verb. Exhausted tension is decadence. So, we place it on the other side… This time, the exhausted tension is no longer in the infinitive, but in the past participle “sang”. You’ll notice that the exhausted tension can be taken up again, as I said earlier, it can be taken up again from an external point of view, and that’s what happens with the infinitive, when one says “to have sung”. You take up the tension from an external point of view. So that here we’ve already achieved a movement that justifies putting on the same line, provisionally… a position-sequence, that is, one that is like… one that reunites and prolongs the incidence in a decadence that is being formed, a sequence that will be represented by the gerund, “singing”.

The first level of chronogenesis will therefore focus on incidence-decadence, as a signified of potentiality, and the three key positions, the three points of view of the verbal linguistic sign, are: the infinitive, the past participle and the present participle, which then take on a signified of effect. You see, it’s the same principle. This is what he calls the first stage of chronogenesis, namely, it’s a mode as nominal of the verb. It doesn’t matter why, he says, it’s the mode closest to the state of the noun to which I only briefly alluded earlier.

And then – I’ll go quickly because you’ve already understood everything he says – the second stage of chronogenesis is the subjunctive. What does the subjunctive bring in? It introduces some very, very new things compared to the first stage: it brings in the introduction of persons. But above all, it brings… it doubles the incidence and decadence of another movement. Guillaume’s texts are extremely complex. It seems to me that he sometimes uses the terms ascendance or descendance, a movement of ascendance or a movement of descendance, which would occur at the level of the subjunctive. But what does this mean? It’s that the subjunctive, ascendance, would be the relation of the term, of the linguistic unit, with a virtual… it would be the process of the virtual, it would be the signified of potentiality, or of the possible – I consider these two notions to be equivalent – which is to say that the process of ascendance would consider the totality of the possible. Example: “that I love”, present subjunctive, where I not only consider love as possible but I consider it as referring to a totality of the possible.

What would descendance be? I think Guillaume is trying to tell us something like this: even within the possible, even without involving the real, even within the possible, there are irreconcilable possibilities. I could say, for example, this is another point of view… from a certain point of view, I could say: speed, safety – what else? I can’t think of anything else to add – speed, safety, etc. form the totality of possibilities from the point of view of the car in its ideality. And then I would say, and it’s not opposed to that, I’d call it the point of view of ascendance – and this example is my responsibility… as it’s not in the book. It’s the point of view of ascendance. And so, I would say, be careful, even from the point of view of the possible, the more speed you have, the more you risk, the less you risk. Since it’s a risk, you won’t be safe. The more safety you have, the less speed you have. Suppose that’s true. Don’t say it’s not true. I’ll have to find another example, but it will be very tiring.

Here, not everything is, as Leibniz would say… not all possibilities are compossible, not all possibilities are reconcilable. So, you have a movement by which we rise towards the whole of possibility, and another movement by which the possibilities dissociate. The first moment is “that I love”, and the second moment is “that I loved”. And there are some sublime, some very beautiful passages in Guillaume that show why past subjunctive tenses have the tendency to disappear in French, because… according to him, it’s not because they’re formulas that sound barbaric. On the contrary, he says, if they sound barbaric, it’s because they imply a contradiction. Tension implies a contradiction. If I say “that I love” and then if I say “that I loved”, there’s a kind of double, contrary tension. You see, on this line, he flanks us with the two subjunctives that refer to what I call, roughly speaking, movement of ascendance and movement of descendance in the virtual or in the possible.

Third level, and it’s a chronogenesis. There, I’ll have… present subjunctive and past imperfect subjunctive – you see, he defines each very well. What it engenders, you have to read horizontally, while chronogenesis, you have to read vertically. At each stage of chronogenesis, you can see that he has generated verbal units defined as positions with regard to a thought process. So, at the first level, he defined three positions: infinitive, present participle, past participle. At the second level, he has defined two main positions: present subjunctive, past imperfect subjunctive. On the third level… what will we have? That’s where the present or the real comes in. That’s why it is so important to show that for the subjunctive, we remained precisely in the virtual and the possible, even when incompatibilities specific to the past imperfect subjunctive begin to emerge.

So, what will the present do here? It’s very interesting. Why does he want to introduce… the present is the real. He’ll jump to a position for the present. And you’ll see that in its own way the present takes up both the movement of incidence-decadence and the movement of ascendance-descendance. In fact, if I understand correctly, he’s saying something like: every actual moment is present, every actual moment is present. And at the same time, every present is defined by its difference from the former present, which is no longer present, and the future present, which is not yet present. So, from a certain point of view, I can say that the present is the Whole of the actual, the Whole of the actual, and at the same time, the present is what differentiates the actual from what has ceased to be, or from what is not yet.

Yet it depends on what… it depends on what I can put on my line, which you can now see is going to be the indicative line… so I’ll have my three lines: nominal mode of the verb, subjunctive mode of the verb, indicative mode of the verb, with the key position of the present tense. And in the position of incidence, I will have “I sang”, that is to say the imperative… no, sorry, what am I saying, past simple. On the contrary, in a position of decadence, I’ll have “I was singing”, the simple past continuous. In fact, when I say “I sang”, well, I’ve already finished singing. But in the past tense, I’ll have a position of incidence: I sang, I sang… the past simple. When I say “I sang”, the past simple means that I started singing in the past, and there you have a position of incidence linked to the past and to the dimension of the past.

On the future side, you have… a future of incidence, “I will sing”… “Yes, I will sing… tomorrow I will sing”, and then you have a position of decadence. In which case you will say “I will have sung”. Ha ha! No… you haven’t understood. The auxiliary… “I will have sung” implies an auxiliary. And the auxiliary is a reprise, the auxiliary is always a reprise. It can’t be “I will have sung”, it’s “I would sing”. You might say this is the conditional but it’s not a mode, it’s a false mode, it’s a false mode, “I would sing”. It’s in a position of decadence or descendance, since both will enact – it’s going to get so complicated – you see how both are going to enact, I would say, a position of descendance since, in effect, when I say “I would sing” in the conditional, it requires that in terms of possible events, there isn’t an incompossible that prevents my singing. Here, I’m no longer putting myself in a position of ascendancy, in a whole of the possible – “I will sing” – but on the contrary, in the possibility that there are irreconcilables in the possible: “I will sing if you ask me nicely enough”. If, if… and so on… I will sing.

So, having said all that, I’d just like to confirm something. You can see what type of linguistics we’re dealing with here… it’s a linguistics of a very, very odd kind. I mean, every time I can go back to my theme… What’s necessary is not that the examples be very clear. What’s enough for me is that the whole system of examples I’ve given you, should help you familiarize yourselves with this idea. It’s the familiarity with the idea that’s important to me, that you develop it… In each case, he will define a signified of potentiality which, please understand this well… which is above all not an essence, nor a concept, but a dynamic or a process, a thought-process that he calls the signified of potentiality. A linguistic unit is a sign whose meaning is the signified of potentiality. But as a sign, the linguistic unit implies that it occupies a position… a position taken from the process. Not only one, but one position among a set of possible positions: the set of possible positions of the indefinite article “a”, and the set of possible positions of the definite article “the”… [Interruption of the recording] [1:00:48]

Part 2

… If you consider, lastly, if you consider the linguistic unit in one of its positions… in one of its positions, you would say that this is its signified of effect. So, according to Guillaume, the linguistic sign is constituted by the sign and its signified of effect, and yet the linguistic sign refers to a pre-linguistic condition which, at the same time, is a correlate of language, which does not exist outside of language, but which is not itself linguistically formed. That’s what’s important, the non-linguistic correlate of a language system.

Hence, I would say, for linguistics, there are three fundamental consequences… for this type of linguistics. And here again, if we take up the example of “that I love”, it seems to me that it’s around the following three questions that you must decide whether you are Guillaume’s disciples, or whether you refuse to be his disciples, or else, it’s of no importance to you one way or the other.

I would say, the first important point in this type of linguistics is the affirmation of a prior, pre-linguistic matter… but prior is not a good word. Once again, I use prior not from the point of view of existence. It’s not a question of saying, there’s a pre-linguistic matter before language. It’s a de jure pre-existence, although it’s a correlate of language. A correlate… when I say it’s a correlate, I mean that as a correlate, it’s not linguistically formed. Language refers to a correlate that doesn’t exist outside of it and yet, by itself, in itself, is not linguistically formed. This is what we call “matter”. I would say, perhaps, underlining three times the word perhaps – please don’t misunderstand me – perhaps, perhaps, perhaps… this is what Hjelmslev means when he speaks about matter. In any case, that’s what Guillaume means when he speaks about the signified of potentiality.

And you can see why all linguists are opposed to this point of view, since it seriously calls into question the sufficiency of language and the possibility of treating language as an abstractly closed system. Now, the possibility of treating language as an abstractly closed system – they know very well, I mean, linguists know very well that it’s not a closed system in concrete terms – but they claim the rights of being scientific, namely: to treat their object as a closed system. Well, all linguists will obviously oppose this point of view, denouncing Gustave Guillaume’s insistence on an old metaphysics, an old metaphysical point of view. Well, is this old metaphysical point of view simply an old metaphysical point of view, or a call for a new linguistics?

Second essential point. All linguists since [Ferdinand de] Saussure have told us that language is a system of differences. You know this, I suppose, and it’s even in this sense that it constitutes a system. As we’ve seen, it’s a system of differences at the phonemic level. A phoneme exists only in its difference from other phonemes. To take my example, /b/ only exists in relation to /p/ under certain determinable conditions. This is why a phoneme is not a letter. Similarly, a system of oppositions, a system of differences, as we’ve seen, is paradigmatic. So much so that I quote a famous sentence by Saussure: “[Signs’] most precise characteristic is in being what the others are not”.[3] In other words, we must attribute to a sign only those phonic elements or semantic elements by which it is distinguished from another. Right.

I’m saying that all linguistics from Saussure onwards, and in linguists very different from Saussure, for example [Roman] Jakobson, or even Hjelmslev, it seems to me – it would be more… it’s perhaps more complicated. Hjelmslev is so… But anyway, among the distributionalists, among all of them, it seems to me, the essential idea is that language is a system of distinctive oppositions, exclusive of one another, where terms exclude one another other, a system of distinctive and exclusive oppositions, sometimes binary – think of Jakobson’s efforts to make binary oppositions at the level of phonemes – sometimes multipolar. But the idea of language as a system of difference is most often interpreted by linguists as an appeal to distinctive and exclusive oppositions.

Everything I’ve said allows me to move very quickly. Guillaume, as far as I know, is making a real shift here. Of course, there are oppositions… of course, of course, of course, but that’s not what language is in essence. What is language for him? If I want to sum it up, it is a system of differential-inclusive positions. He replaces distinctive-exclusive oppositions with differential-inclusive positions. Let me go back to my simplest example. Take the indefinite article, the movement, the signified of potentiality, the movement of particularization. The indefinite article will have a whole series of differential positions that will be the points of view on the cuts of the movement of particularization, and they are inclusive because each one preserves something of those that precede and prepares something for those that follow. And Ortigues understood this very well. I’m reading, because it seems to me one of the essential points, even if it’s very odd that he didn’t see, I don’t know why, the history of the signified of potentiality and of… and yet he has clearly understood this point “It’s impossible to see” – pages 98-99 – “it’s impossible to see in the various linguistic units only oppositions of values” – which was Saussure’s great notion – “… only oppositions of values, since these values are defined by the positions they occupy in a hierarchical system of functions”.

It’s the end of the sentence that doesn’t work for me. It’s not in a hierarchical system of functions, it’s in relation to the signified of potentiality, which is to say in relation to pre-linguistic matter, precisely because as he didn’t want to take account – but I know why, it’s because Ortigues is a Lacanian, that’s why he couldn’t do it – he couldn’t take into account, he couldn’t, as he wanted both to make Guillaume an essential element in modern symbolic thought and to take account of the history of the signified of potentiality… in other words, he couldn’t be Lacanian. He wanted to be both a Guillaumist and a Lacanian. That was his own choice. What a strange choice!

But then, he’s seen it correctly, but in fact it’s not a question of a hierarchical system of functions at all. It’s a question of a set of movements, movements of thought that constitute signifieds of potentiality. But that doesn’t matter. He continues: “Between the forms” – that is, linguistic forms in the manner of Saussure – “between the forms, it is sufficient to admit a principle of external or classificatory difference proceeding by reciprocal exclusion, but it is necessary to admit between the functions” – which I translate as between the points of view of the signified of potentiality – “it is necessary to admit between the functions a principle of internal differentiation such that each position in the system is inclusive of all those subordinate to it”.

In other words… well, let me put it another way. It’s no longer – and this is really a crude summary I’m making here – it’s no longer a question of a distinctive-exclusive oppositions, a system of distinctive-exclusive oppositions. It’s a matter of a series of differential-inclusive positions. It seems to me that this is linguistics at its most original… You must understand that, at this level, it’s not really a question of… – I have a feeling I’m right – it’s not a question of discussing, it’s not a question of saying… First of all, try to feel the novelty of this. And then, if need be, depending on your own problems, you might say to yourself, Ah, well no, yes, I myself feel more drawn to the side of the oppositions because I find it more useful. It serves you better, it serves you better to set, your, to pose your own problems. And to feel that Guillaume achieved something that in my view was not taken up by linguistics. They may have taken it into account, many linguists have taken Guillaume into account, but the essential thing is that what we could call Guillaume’s originality, precisely insofar as it went beyond the theory of the signified of potentiality, was lost, was necessarily lost because it derived from the signified of potentiality.

Third point, which is going to be very important for us, because that’s what I wanted to get to. Well, you understand, you understand, you understand… what happened, and what does it mean, the expression we use, sometimes semiotics, sometimes semiology? Well, it’s not difficult, it’s not difficult. When you look at semiologists and semioticians, you realize that if there’s one notion they don’t discuss, it’s the sign. At first, this may surprise us a little. How can semiologists not speak about signs? At a second glance, we’re even more astonished, because we realize that they actually detest this notion, and that they declare it pre-scientific. So, they are in some way very deeply against it. So, I’d say, provisionally if you like, a definition of semiology could be… it’s a semiotics that doesn’t speak of signs and that operates without signs.

And it says so itself, since it claims to constitute itself as a truly rigorous discipline, on condition that it renounces the notion of the sign. Those interested in this point will find an excellent appendix in [Oswald] Ducrot and [Tzvetan] Todorov’s Dictionnaire de linguistique, published by Éditions du Seuil.[4] The last section of the dictionary, which is a fairly short appendix, explains why modern semiology has settled its scores with the notion of the sign, citing three examples. It’s very scholarly in the best sense of the word, and very clear. They explain, first of all in a purely logical sense, but just so as to understand, that semiology was based on the following fact: the famous Saussurian signifier-signified distinction, the signifier and the signified being the two sides of the same linguistic reality, two sides of the same linguistic reality. The sign was in fact this two-sided element, signifier and signified.

Semiology developed from the realization that the balance between the two sides was necessarily unstable, and that either we would have to give precedence to the signified, and fall back into the worst of the old metaphysics, or we would have to give precedence to the signifier. Which meant what? It meant that in every signified there remained the trace of the signifier, and that it was the signifier that had primacy in the signifier-signified relation. And very schematically, from a very general point of view, this is [Jacques] Derrida’s theory at the time of his Of Grammatology,[5] to explode the notion of the sign in favor of the signifier and to threaten us by telling us that if you don’t, you’ll be forced to grant primacy to the signified, and by granting primacy to the signified, you’ll go back to the old metaphysics of essences or the intelligible, that would be primary in relation to the language system.

The second fatal blow, logically speaking – I say logically because this second blow chronologically preceded the first – came from Lacan, who this time didn’t even pose the problem at the level of the signifier in its relationship with the signified, but at the level of what he called the “signifying chain”. It was the signifying chain alone that would suffice to shatter to a large extent the notion of the sign, rendering it radically useless. To what extent… to the extent of Lacan’s famous interpretations of Saussure’s hyphen in the signifier-signified relation in his own celebrated formulas, where this hyphen was to be understood as a bar… as a bar. So, semiology would be the science of the signifying chain, or the discipline dealing with signifying chains – in other words, psychoanalysis as the discipline of the unconscious in its relation with language systems.

The third stage – and you can find out more about this third stage if you’re interested – takes the sign beyond the signifying chain to Julia Kristeva’s original notion of “signifiance”.

Fourth… Oh, there are more, surely… but that’s enough for now, that’s enough, there are more surely, there are surely more. So, I’d say, let’s look at the other side…. So, I would say, what we call semiotics is a discipline that deals not with the sign but with the signifier, signifying chains or significance, both in language and in any kind of language system. From that point, both language systems of different types, such as non-verbal languages, and language itself, will exclude anything that may be called a sign. And indeed, if I return to Christian Metz, you’ll find in his book Film Language,[6] an explicit denunciation of the notion of sign.

Following [Charles Sanders] Peirce, I will call semiotics a discipline that has the following two characteristics: firstly, it maintains the absolutely indispensable character of the sign, and secondly, it engenders the operations of language systems – and here I mean language systems and not only speech. It engenders the determinations of language from a non-linguistic matter that involves signs. I feel – but this is just my feeling, I may not be right – I feel very close to semiotics and very far from semiology. Which means what – we’ve almost finished the difficult part – which means what?

I’ll take up again the doubts I expressed about semiology in cinema. My first doubt was that cinematographic semiology seemed to me to be based on three points. And I had my doubts about each of these points. The first point was narration, which was presented to us as a fact, but it seemed to me that narration was never a fact, it was neither a given of the image nor the effect of a structure beneath the image. But it was the result – as you can see, I’m keeping my semiotic promises here – it was solely the result of a process affecting images and signs, a process of specification, a movement of specification. I don’t need to go back to Guillaume’s movements, which were determined by grammar. If I’m dealing with cinema, I obviously need to find completely different movements. When I speak about the first movement of images, I mean the movement of the specification of the movement-image. As we’ve seen, the process of specifying the movement-image constitutes three kinds of movement-images: perception-image, affection-image, action-image. This has nothing whatsoever to do with narrative. I only obtain narration when, according to a law that is the law of the sensory-motor schema, I combine these three kinds of images.

So, you see, here I feel very much a disciple of Guillaume. I would say exactly that there’s a process of specification that acts upon images, pure movement-matter, it’s a movement-matter, which gives us the three kinds of images and which constitute precisely a non-linguistically formed process, and yet one that fully constitutes the first stage of semiotics. The process of specifying the movement-image in terms of three kinds of images is non-linguistically formed, even though it is perfectly formed cinematographically.

Second point: Can we assimilate the cinematographic image to a statement, as semiology does? No. In fact, my trouble stems from this: if you equate it with a statement, it’s an analogical statement. But you can’t equate the cinematographic image with an analogical statement unless you’ve already bracketed its movement. In fact, the cinematographic image at this second level is inseparable from a process that we’ve seen to be that of differentiation and integration, a process very different from that of specification. The process of specification, you’ll recall, was once again the specification of the movement-image in terms of three main types of image. The process of differentiation-integration is the dual aspect of the movement-image insofar as, on one hand, it refers to a Whole whose change it expresses – integration. Secondly, movement is distributed, divided between the objects framed in the image. This is differentiation. The two never cease to communicate, to form a circuit. In what sense? In the sense that the linkage of the specified images – you see, I return to my first process, images specified in terms of three kinds of images – a linkage of specified images doesn’t happen without the images thus linked becoming themselves internalized into a Whole, at the same time as the Whole is externalized in the images. I can say that my second process, my second process of differentiation-integration, is directly linked to the first.

Regarding the time-image, if I were to speak about time now, I’d again take up – and obviously this wouldn’t be the same process as Guillaume’s, here I’m going very fast – in this case, I’d distinguish two processes concerning images, their matter and their relations: a process of serialization of time, as we’ve seen, the series of time, and a process of ordering time, of relations of time, the coexistence of relations of time. I repeat: there’s nothing linguistic about these two processes. They constitute – by reacting upon cinematographic images – they constitute the signs of time, just as earlier I had the signs of movement. In other words, these processes taken together and the play of images and signs that result from them, in no way constitute a language system, any more than they do a language. What is it, then? That’s why I needed it so badly: it’s the non-linguistically-formed correlate of all language systems and all possible languages. It’s Hjelmslev’s matter, non-linguistically formed matter. It’s Guillaume’s signified of potentiality.

That’s why I needed this long analysis. For my purposes, it’s what I’d call the enunciable. It’s not enunciations, it’s the enunciable as matter. This is the object of pure semiotics. Pure semiotics works with images, signs and non-linguistic processes that determine these images and signs. In this way, it forms an enunciable. The enunciable is neither language system nor language, but the ideal correlate of all language. It’s not a linguistic process. We’ve seen what linguistic processes are: they’re syntagms and paradigms, syntagmatic and paradigmatic. The processes I mentioned – specification, differentiation-integration, serialization, ordination – have nothing to do with this, they’re not linguistic processes.

In semiology, I can’t understand how they’re able to escape from what seems to me a vicious circle, that is, telling us that the cinematographic image is a statement since it is subject to the linguistic processes of syntagm and paradigm, and at the same time telling us that it is subject to the linguistic processes of syntagm and paradigm because it is a statement. For me, the cinematographic image is not a statement, but an enunciable. The difference is immense. For me, the cinematographic image is not subject to the linguistic process of syntagm and paradigm. It is determined by and in. It is determined semiotically and not linguistically, by the list of non-linguistic processes I have just recalled.

It’s in this sense that I’m a proponent of anti-semiological semiotics. I’m in no way saying that I’m right. It would be quite enough for me if you told me that you understood the difference between the two points of view. If I was told… if I was told that I’m maintaining an old metaphysics with this conception of the enunciable, I’d say: What an honor! I’d just like to add that I’d like you to sense the Bergsonian aspect of all this. For this pre-linguistic yet language-related matter is entirely in line with movement and temporality as defined by Bergson, which is to say a kind of thought-movement or thought-process regarding which we take instantaneous views, which is why Guillaume remained very Bergsonian.

And I’ll finish on this note. Yes, you can see why we’re in a very joyful position! We’re done, the hard part is over! We’ve changed everything. I mean, we’ve changed everything because where the others were in difficulties… no, rather, where the others were having it easy, we were in difficulties. That happens all the time. But now, where they got into difficulties, it’s going to be absolutely easy for us. What’s going to be easy for us? Let’s not exaggerate. With pure semiotics, which speaks about anything but language and language systems, it’s a bit awkward, I must tell you: we’re talking about the non-linguistically formed conditions of all languages and language systems. So, we’re making the prolegomena to all linguistics, something Hjelmslev himself didn’t manage to do.

But then, what are we going to do with language systems? Because in the end, pre-linguistic matter should be more than enough for us. Oh no, the enunciable has to be enunciated, of course. The enunciable must be enunciated. I call… I call “language system” any statement or enunciation whose object is all or part of the enunciable. The enunciable, you grant me, is neither related to nor assimilable – what we’ve called the enunciable, I hope you understand – is assimilable neither to the object to which the enunciation relates, nor to the signified of the enunciation, nor to the signifier of the enunciation. We are in a different area here. So, my problem is obviously that the enunciable will be grasped in acts of enunciation. How can we design the act of enunciation so that it expresses the enunciable? Or more simply, I’d say here, almost as if it were valid for the moment, the act of language, or if you prefer, speech acts. What is the role of language acts and speech acts? Well, as you can see, it’s no coincidence that semioticians distinguished between them, constructing a separate code for the audiovisual. For us, it’s not a separate code at all.

We will therefore call a properly cinematographic enunciation any act, any speech act that refers to an enunciable, meaning a linkage of images, an image or a linkage of images taken from the processes previously defined. Needless to say, silent cinema, no less than talkies, presents us with acts of language. There is no cinema without acts of language. Clearly, from the silents to the talkies, the status of speech acts is likely to undergo major transformation. But it’s not with the talkies that properly cinematographic speech acts emerge. In other words, there are enunciations that are properly cinematographic, but that can’t be reduced to literary enunciations, theatrical enunciations or… anything else.

So, our task from now on, and that’s why we’d made it clear that this part would be studied from two angles – concerns the second aspect. What is a cinematographic enunciation? What is its relation with matter, with the movement-image or the time-image that we’ve just been discussing? What is its relation with the non-linguistic processes we’ve just been talking about? So, we’re now in a position to begin our study of cinematographic enunciations from the point of view of both silents and talkies. Well, all that was difficult, but we’ve finished with the difficult part… [Interruption of the recording] [1:43:33]

Part 3

… but I forgot one little conclusion, as it was essential, that the whole problem, the whole initial problem, was: How could the first thinkers of cinema, or the first great filmmakers, equate cinema with interior monologue? As you can see, there’s no longer any problem for us, because as I was saying, the interior monologue is a very interesting thing. But why? Because the Soviets tried to understand the interior monologue as a proto-linguistic system. A proto-linguistic system can mean many things: it can mean a primitive language, an infantile language, we’ve seen all this with [Lev] Vigotsky, when I was referring to this very interesting author, fine.

And for us, following our conclusions, we can only say – on our own account, because this is how we proceed, that’s what we want, that’s how it is… for us, it doesn’t mean so much – the interior monologue is not a language system. We don’t even need to invent a proto-language, you see, we don’t even need a proto-language. What we now call interior monologue… and we’ll say: well yes, cinema is interior monologue. But in what sense? The interior monologue isn’t a language system, it’s the enunciable. It’s the enunciable of language systems. In other words, it’s a non-linguistically formed, yet cinematographically formed matter. If it weren’t cinema, I’d say it was aesthetically formed matter that is not linguistically formed.

So, I can say, yes, cinema is interior monologue, provided I’ve given interior monologue the status of being the non-linguistic matter that conditions language systems and the operations of language systems. But I can only say this for one case – and this is where you’ll have to be kind enough to follow me right to the end – I can only say this with regard to the movement-image and the processes of the movement-image, the non-linguistic processes of the movement-image. The non-linguistic processes of the movement-image were its specification in terms of three types, and its integration-differentiation. So, here I can say yes. Here, the set of movement-images and their signs constitute the interior monologue, that is, the enunciable, or the non-linguistically formed matter of the language system. It’s not part of the language system, it’s the non-linguistically formed matter of the language system. So, what does the time-image do with this? We’ve seen that the time-image is caught up in other processes. It, too, forms a non-linguistically-formed matter, but a very different one, and one that will no longer be expressed in the form of an interior monologue. So, what form will it take? Everything is just right, perfect, we’ll only be able to say when we’ve studied the question of properly linguistic… no, sorry, properly cinematographic utterances.

So next time, when we return after Easter, I suggest that those of you who would like to do so, reflect a little on this semiotic-semiological relation, as we’ve now been doing for several sessions. Then we’ll have another session, with you intervening. I can already see who might speak… [Giorgio] Passerone on Pasolini, Eric [Alliez] also on Pasolini or on other things, some of you on semiology… and we can see if there are things we need to fine-tune. I mean, it doesn’t make sense to do it now, we don’t have enough time, and then it would be… It’s better to finish on a simple note. That will get us going again, and it will be after Easter.

So there comes the always delightful moment when I say to you, well, let’s forget everything we’ve done so far. We’ll just have to remember it after Easter. But for now, we can completely forget, and then we will start again, start again from scratch, we can start again from nothing or from very little. As I was saying, well, now we have to keep in mind, however vaguely, this cinematographic enunciable, but an enunciable that refers to acts of enunciation.

So, there are cinematographic enunciations. What is a cinematographic enunciation? Do you realize what we’re dealing with here? Because as I was saying, in my view, we’ll be forced to go through three stages, to distinguish three stages. There is no unity in talking pictures. We’ll have to distinguish between the silent period, where there are already cinematographic utterances, and the time of the talkies, which is a vast reworking of cinematographic utterances that will give rise to genres, that will bring new genres to cinema. And contrary to what people say, with no risk of exaggeration, these are lousy films. Well, there’s nothing wrong with lousy films! They’re lousy, and that’s that. I don’t see what the problem is? There’s never been a problem in talking about cinema-theater. Never, except, once again, when the films are very, very bad, but when the films are very bad, they don’t seem to pose a problem, they don’t pose a problem!

You see, when, for example, I take a major genre that coincides with the arrival of the talkies like American screwball comedy, it never stops talking. It never stops talking. Imagine that the equivalent in the theater is grotesque. Yes, it is. Long after American comedy, someone in the theater will manage to produce effects very similar to those of American comedy, but in terms of a completely different level of seriousness. It’s in the periods when he plays the comedian, in fact, it’s in that period of Bob Wilson’s productions, which are theatrical masterpieces, but which obviously presuppose cinema. Without cinema, he couldn’t have done that. Okay.

But if you think of an American comedy, well, it’s amazing the way the voices overlap. It’s all a matter of having everyone talk at the same time. Everyone at the same time, though there’s always one who is unable to do so, Ah ah ah… That’s why it’s cinema, not theater. You might try to do that in theater, but the effect would be pitiful. It goes off in every direction, pure conversation, independent of any object. That’s American comedy, pure conversation independent of any object, it’s an invention of cinema. Theater had never risked anything like that. And once again, when Bob Wilson did it himself – at a time well after it’s cinematic heyday – he did it using his own genius, these conversations that go off in every direction, well, we might say, they’re crazy! At which point we become aware of something more profound. That’s why American comedy is so striking. It’s a very, very important element of cinema, it concerns people who are crazy, but what you think is craziness is simply the ordinary madness of the American family, and this is how it is presented, the ordinary madness of the American family. And we find ourselves saying that every time we listen to a conversation, we realize that they’re the ones who discovered conversation.

Take a conversation in a restaurant. We sometimes say… you see, very, very interesting studies have been carried out on schizophrenic conversations, for the way they follow difficult and obscure laws. This is very important, you know. There’s a question of distance. You can get close, but not too close, or you can move further away, there are questions of territorial boundaries. I’ll speak to you at such and such a distance. If you breach this distance, I won’t talk to you anymore, and so on. There’s a whole problem of conversational space.

Well, this has been fairly well studied from the point of view of schizophrenia – in particular there are some very fine texts by R.D. Laing on the conversations of schizophrenics, though he doesn’t give enough importance to the spatial aspect. However, other psychiatrists have understood these problems of space. For example, those of you who frequent La Borde, like Erik, well… when you talk to a schizophrenic, they can be very approachable, but you can’t speak to them any old way! I mean, first of all, there’s a form of politeness. And then, if you get too close, even when they ask you for a cigarette, if you get too close… well, no, it’s not okay. But also, if you stay too far away, they could become aggressive, out of fear, and so on… what we call being at ease with others, being at ease with those who are different… well, the nurses have a way with a schizophrenic, just like someone who has a way with children.

But why do I say this? Because it’s not conversation that provides a good way of defining schizophrenia, it’s actually the opposite. Schizophrenia is the fundamental criterion of any conversation. If you go into a café, you sit down – I don’t do this anymore, but I used to like doing it a lot – like many of you, just to sit in a café and listen to people, but we need certain conditions. And you find yourself thinking, these people are completely bonkers! They’re raving lunatics, the way they joke, the way they pretend to be angry, the way one subject cuts off the other, the way one is always silenced, going Ah ah ah! Wanting to say things but never being able to… I mean, it’s a bit like that in [Michel] Polac’s shows…[7] completely from a psychiatric point of view, because notably there’s always one guy who you know in advance will never speak. He starts… Ah! And then there’s the one that you know… a guy who’s like Katharine Hepburn, not as beautiful as Katharine Hepburn but… because that was Katharine Hepburn’s genius, the way she spoke so fast, so incredibly fast, and with such haughty insolence.

There’s also something interesting about American comedy in the way it can be so political. It’s very political. Katharine Hepburn’s haughty insolence is a wonderful thing, and the way she decks the male lead, no matter who the actor is! Besides, the role of the actor playing against Katharine Hepburn is to try, as they say, to get one over on her. And he’s never able to. He’s never able to, and not simply because she talks so much. She’s always so over the top in what she says that the guy is always one step behind. So, it’s very, very odd, and it’s a discourse that takes off in all directions. It disappears off-screen and then comes back from the other side… it’s very striking, it’s… well, I’m just saying.

So, there are cinematographic utterances in the talkies. But that’s not all. There are extraordinary cases in American talkies, and even in films that… perhaps especially in film noir. I was quoting American comedy, but in detective films, there are tricks that are so good that you can no longer assign, you can no longer assign a line that was said by one actor, it could have been said by the other. Not only is there an effacement of any object of enunciation, the conversation can be about literally anything, but there’s also an elimination of the subjects of enunciation, who become completely interchangeable.[8]

And the most striking case of this, obviously – where it goes the furthest – is when it’s a conversation between a man and a woman, when it’s in a flirtatious conversation. There’s one case that I find quite sublime. This time, I want to cite two actors because there are times when you have to cite actors, and this is Lauren Bacall and [Humphrey] Bogart. If you take [Howard] Hawks, there are two Hawks films, well, in the sort of immediately amorous, immediately passionate relationship they have, if you close your eyes and if there wasn’t a female voice and a male voice, what one of them says, the outrageous things they say make you think it must be the man who’s saying this.[9] There’s a kind of absolute reversibility of points of view in the conversation, where it becomes impossible to assign a subject of enunciation. You just have a whole slew of utterances. All this is to say, well, how this marks one stage of the talkies.

But what we’ll also be looking at – and this is just to give you an idea of the kind of program we’re going to cover, which will be very rich – is that, after the war too – which is why the real frontier, the real rupture, if there is a rupture, was not in the transition from the silents to the talkies – but after the war, when the talkies assume a completely different status… a completely different status. And if you think, for example, of the great, great contemporary filmmakers of sound cinema, well, immediately – independently, of course – there’s [Alain] Resnais, there’s, well, there are many, but, but those who really transform sound cinema into a modern problem and do so in very specific conditions, this would above all be [Jean-Marie] Straub… the Straubs and Marguerite Duras. Well, it’s clear that this also represents a completely new type of cinematographic enunciation.

So, it’s quite a big task we have in front of us, but once again, as you can see, it will be quite easy – no, not in the last case I mentioned, not in the case of the Straubs, for example, the Straubs are very demanding but yes, it seems to me that there has been a major attempt to analyze these… – and I think we’ll have something to draw on here in terms of formulating a general theory of enunciations. There will be something we can learn from these three stages: the silents, the early talkies and modern sound cinema.[10]

So, I just want to say very briefly – because we’re coming to the end of the session – I just want to say, yes, in fact, as I started to say, in so-called silent cinema, what do we have? As you’ll recall, I was referring to remarks made by [Jean] Mitry and [Michel] Chion, when they said: Well, actually no, silent films were never really silent, because they have articulation, they have phonation. People never stop talking, you just can’t hear what they’re saying. Okay, so there’s no such thing as silent cinema. Mitry and Michel Chion are absolutely right to say: it’s not silent cinema, it’s not they who are mute, it’s you who are the ones who are deaf. It’s the spectator who’s deaf, it’s a very different situation. I would say that if there is a silent cinema – and here I’ll digress for a moment – it’s in Marguerite Duras’s work, when she eliminates the movements of the actor’s phonation, to begin with the simplest case.

So, what’s happening here, since silent cinema isn’t silent, there are utterances. As I said, it’s not difficult, you have two images, and silent cinema is defined by the coexistence of two images. There’s an image that is seen and an image that is read. The image that is read – let’s start with the simplest element – is called the intertitle. We’ll leave aside the all too obvious objections that there have been silent films without intertitles. Oh, well, you have to explain that one, it’s going to be a problem. Can the image that is read be reduced to the intertitle? No, of course not, but let’s start with the biggest, the simplest, the most obvious.

But I would say, take a good look at what happens when we are in the regime of intertitles. Seeing and reading are two functions of the eye. So, I could say that a cinematographic image, at this stage, is visual. It is visual. Quite simply, the eye has two functions: regarding the seen image, its function is vision. As for the read image, its function, as in the case of intertitles, its function is reading. These are two very different functions. What happens to the intertitle considered as a read image? Well, what strikes me is that the read image always assumes a kind of abstract universality. It assumes a kind of abstract universality to the point that, no matter how directly it is proposed to us, we always transform it into indirect style.

For instance, I once gave you an example, I think, and this is where I’m going to start from again… take a seen image. We see a cruel-looking man, who pulls out a knife and brandishing his knife advances towards a poor young girl – I’ll simulate this for effect – and then there’s the intertitle: “I’m going to kill you!” Right. It’s obvious that we, the viewers, read: “He says he’s going to kill her”, since, even in the idiotic notion of identification, which really seems to me – you know this business stories about identifying with, not identifying with – even if there is identification, it’s with the seen image and not with the read image. The intertitle “I’m going to kill you!”, I actually read as: “he says he’s going to kill her”, that is, the read image is read in indirect style even when it’s presented in direct style. In this sense, it takes on a kind of abstract universality.

Whereas… I’m getting ahead of myself, but what I’m saying is that it applies to something of the order of an any-law-whatever, that’s what abstract universality is. He says he’s going to kill her in the name of the law of the strongest, even if it’s the strongest, it’s still a kind of law, whereas the seen image is charged with everything that could be called, it seems to me, everything that I would call “naturalness”, naturalness. There’s something natural about it. It takes on the natural aspect of things and beings. And I’d even go so far as to say that this is what constitutes the beauty of visual images in silent cinema, and that this, as we’ll see, will necessarily disappear afterwards. That’s why, I mean, there’s a naturalness to the visual image. It’s as if the visual image took on the aspect of nature, while the read image, the intertitle, took on – well, what isn’t nature – the abstract universality of law. You’ll tell me: Oh, you’re going too fast, too fast not in the sense of being too difficult, but in the sense of being too arbitrary. A film critic, Louis Audibert…[11] [Interruption of the recording] [2:08:28]

… So, this is not Murnau case… but if the case of Murnau has served us well, it’s because, even when it’s not Nanook of the North [1922] and when it’s not Tabu [1931], what does silent cinema basically show us? What does it show us? It shows us a society. It shows us the structure of this society. It shows us the roles in this society: the boss, the worker, the soldier and so on. It shows us the places and functions in this society. It shows us the actions and reactions of the people who occupy such and such a place, or fulfill such and such a function.

Structure-situation, place and function, actions and reactions, all of it social, yes, all of it social. What’s more, it shows us… the visual image of this cinema shows us the conditions of the speech act, meaning, in a given situation, you are forced to respond or to speak. The character speaks or else responds. So, these are the conditions of the speech act. The visual image also shows us the consequences of the speech act. For example, someone says something and gets slapped in the face. I call this the consequence of a speech act. What’s more, we’re even shown the articulation of the speech act. The way a character articulates in silent cinema.

Well, I would say and I maintain, that’s why – I insist on this – even under these conditions, silent cinema, the seen image, the visual image… the seen image presents us with the nature of a society, and the same way that it presents us with the nature of a society, its attitudes and roles, its functions and places, it also presents us with the social physics of actions and reactions. Okay, it’s a social nature, but a society has a nature. For example, there’s a nature of capitalism. There’s a nature of capitalism, there’s a social physics of actions and reactions. There is a social physics of those who command and a social physics of those who obey: action-reaction.

So, I would say that even when the silent image, when the seen image in silent cinema, presents us with the elements of the purest classical civilization, and not a supposedly immediate natural life, this seen image remains as if naturalized. And once again, this is what constitutes its beauty. The set may be deliberately presented in the most artificial way imaginable. But these sets have a nature. Think of one of the greatest filmmakers of silent cinema in this respect, [Marcel] L’Herbier’s sets. Yet these are not natural sets. They’re highly architectural sets, okay. Yet the image is profoundly naturalistic, and it’s this weight of naturalness that forms such a large part of the beauty of the silent image, that makes it something like a secret of the silent image.

I always try to anticipate… well, in this case, I try to anticipate all possible objections. Someone might say, okay, but watch out. That doesn’t prevent me from… They might say: Look at the Soviets, think of the Soviets, the way they never cease to show how society is, in their view, fundamentally transformable through an act of revolution. Yes, and it’s true, I think of a well-known text by [Sergei] Eisenstein, which I mentioned in a previous year, where he reproaches [D.W.] Griffith, saying that when you watch a Griffith film, you always get the impression that rich and poor are so by nature, that it is their own nature.[12]

And Eisenstein objected, saying: This isn’t how I see it. What I want to show is that wealth and poverty are products of society. So, he seems to be opposed to this kind of naturalness. But in fact, he’s not. Not at all. That’s why it wouldn’t be an objection. What needs to be said, and it’s not surprising, is that Eisenstein and Griffith conceive of nature in two totally different, even opposing, ways. For one simple reason, which is that Griffith has an American conception of nature: nature is fundamentally an organism. It’s an organic nature, and society has an organic nature, especially American society. There are sick societies, and there are healthy societies. American society is the healthy society par excellence, the organic society. It’s organic nature. So rich and poor pertain to an organic nature.

As for Eisenstein… although he himself uses the term “organic”, he obviously gives it a completely different meaning, since for him, there are no organic givens of nature, and nature is not defined organically, it’s defined dialectically. And what does this mean? It means that nature is the dual process of transformation, as Marx put it in a beautiful phrase, that it is the dual process of transformation of man’s natural being and nature’s social being. There is a natural being of man and there is a social being of nature, and dialectics is the movement by which man and nature exchange their determinations, which implies a transformation of society.