November 27, 1984

Give me a brain, maybe it means: “I have to realize that one day to the next, the brain is the most fragile, the most random organ of all my organs”.

Seminar Introduction

As he starts the fourth year of his reflections on relations between cinema and philosophy, Deleuze explains that the method of thought has two aspects, temporal and spatial, presupposing an implicit image of thought, one that is variable, with history. He proposes the chronotope, as space-time, as the implicit image of thought, one riddled with philosophical cries, and that the problematic of this fourth seminar on cinema will be precisely the theme of “what is philosophy?’, undertaken from the perspective of this encounter between the image of thought and the cinematographic image.

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

With the possibility that the session’s opening cassette is missing, Deleuze retraces the mutations detailed previously, with the discussion of Pythagoras missing, and he discusses Richard Dedekind’s research on the problem of the continuous, the infinity of a line’s breaks and gaps, and irrational breaks (cf. The Time-Image, chapter 7), linking this to the situations of pre-World War II and post-war cinema. Deleuze discusses the parallel of these postwar cinematographic traits to those located previously in Blanchot and Foucault, i.e., the thought of the Outside, the interstice or interval, first discussing Eisenstein on rational breaks, then shifting to post-war types of irrational breaks (cf. Bresson, Godard, Resnais). Deleuze then moves to the fourth mutation, “give me a brain!”, inspired by cerebral models, our lived relation with the brain, and the possibility of a modern cinema of the brain. Here Deleuze briefly proposes different filmmakers of such a cinema mode (cf. Kubrick, Resnais), [See development in The Time-Image, chapter 8]with the pre-war and post-war developments in the scientific conception of the brain to be considered.

Gilles Deleuze

On Cinema and Thought, 1984-1985

5th session, November 27, 1984 (course 71)

Transcription: La voix de Deleuze, Part 1 [not available], Flavien Pac (Part 2) and Sabine Mazé (Part 3); additional revisions to transcription and timestamp, Charles J. Stivale

Translation: Graeme Thomson & Silvia Maglioni

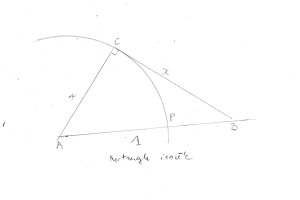

[This session begins in medias res, with Deleuze discussing a geometric drawing on the blackboard, an analysis of the history of the Pythagorean theorem, as he indicates at the end of the session. Given this gap, and the reduced length of the whole lesson (the two parts, 97 minutes, are shorter by a third than usual), it is probable that the tape from Part 1 went missing].

Part 1

[not available]

Part 2

… the distance between these points diminishing to a single point that falls below any length, however small. There’s… there’s no room for anything here. You’ve got your compact, convergent infinite series of rational points. So, there’s no more room, there’s no more room. Okay. Look… now I’m going to make a place for it.

On the line, you see, I construct an isosceles right-angled triangle… and so my line, my straight line, segment 1, with all these points, all these rational points marked by fractional numbers forming a compact, convergent infinite series whose limit is 1. I construct my isosceles right-angled triangle, okay… and I call x the sides of the triangle. I take my compass – here it’s a semi-circle – I take my compass which makes, how shall I say… I mark the point where my circle meets the line AB, and you see my circle has as center A and as radius the side of the right-angled triangle I’ve built on the line. Here, look.

Remember what we’ve just seen with the Pythagorean theorem? We have 12 = 2x2, x2 + x2, and we’re back to our Pythagorean theorem. This point here is… is an irrational number. It’s something wonderful, incredible, incredible! My segment, which I thought was compact, convergent, meaning that it excluded all lacunae… well, here we have a point that’s not part of it. It’s not part of it, it’s an irrational number. With our usual 2/3, 3/4, 4/5, 5/6 and so on and so forth. And smaller and smaller quantities falling below any assignable length… you were entitled to have constituted a series without gaps. But here is a gap. Do you see what I mean? You have to move very quickly in your imagination, in your mind, from one figure to another. Here’s my segment AB. You take it all in your mind, fill it in completely, to infinity, with your infinitely convergent series. And you will think, Phew… I’ve got continuity.

If you leave it at that, you can’t see. I mean, seeing through the mind’s eye, we’re no longer talking about the senses. Your mind’s eye, in the sense that Spinoza says that demonstrations are “the eyes of the mind”. Well, your mind’s eye grasps perfect continuity. You build your right-angled triangle on the segment, you take your compass and what do you make appear? A lacuna. There was a lacuna that your mind’s eye couldn’t see. I mean, it’s not a problem of the senses being imperfect. We’re in the middle of a fundamental paradox, which is an imperfection of the mind as such. It cannot see a lacuna in a straight line.

I mean, you have to try to feel it… it’s getting exciting, well, at least for me. This line is full of holes. This straight line that you’ve drawn is full of holes, not at all as a function of a perceptible imperfection, because it’s a line with perceptible traces. It’s as an intelligible entity that this straight line constituted as a compact and convergent series is in fact a line full of holes. It’s full of holes, and what does each of these lacunae correspond to? It corresponds to an irrational number which is in fact neither an integer nor a fraction. It’s a marvel. Aren’t you amazed? You see, once again, there would be nothing astonishing… and here I insist, there would be absolutely nothing astonishing if we were talking about the perceptible straight line, but not at all. Here we are talking about the intelligible line such as the mind conceives it through a perceptible drawing.

Student: Well, everything changes now.

Deleuze: Sorry?

Student: I don’t know how to put it exactly… if this line is considered as a mental line, and this one on the blackboard is only a figure or a pretext to show what happens inside… it seems to me that our discourse changes completely…

Deleuze: Well, it wouldn’t make any sense if I were talking about the perceptible line. If I told you I was drawing a line, and under the microscope you’d see that this line jumps and that your chalk isn’t evenly distributed etc., that would be of no interest whatsoever. It’s insofar as the straight line is susceptible to a so-called intelligible or purely conceptual definition, that things become interesting. If this purely conceptual line is defined in such a way, by the compact and convergent series, which seems to me to give us an unassailable concept of continuity, and now you’re able to show that this line, constituted by a compact and convergent series, is full of lacunae, literally riddled with holes, that is to say, with points that are not rational… irrational points. But these irrational points, at this second moment in my story, can only be considered as lacunae or holes in the continuity. Hence the bombshell, which is that the compact and convergent or the series of points, the infinite series of rational points, is not sufficient to define the continuous. Is that okay? There’s only one thing left.

So how do you get out of this? You have to, you have to… it all takes a long time, a lot of research, and there have been a thousand ways of getting out of it, more or less successfully. But in the end, the great way, the great way to get out of it only came at the end of the 19th century. At the end of the 19th century, there was a great mathematician called [Richard] Dedekind, d-e-d-e-k-i-n-d, who brought up again the problem of continuity.

And his idea is quite simple. He proposes the following schema, namely that any point – any point, meaning a rational point, or any rational number, it doesn’t matter… – any point or any rational number makes a cut. In other words, the first fundamental merit is that we mustn’t confuse all notions. Earlier, I was talking about a lacuna, now I’m talking about something completely different. Every rational point makes a cut on a straight line, or what amounts to the same thing, every rational integer or fractional number constitutes a cut in the infinite sequence of rational numbers.

Second point: what do we mean by a cut? To cut – our definition has to be very rigorous here because we’re speaking about mathematics – is to divide a set into two classes, one of which will be, as you choose, below and the other above, one lower and the other higher, one before and one after. In any case, the cut will divide our set into two classes. For example, if I take a vertical segment, the point x as a cut divides the set AB into two classes, one of which is above, the other below.

Third point… you have to try to follow this, because it’s not at all difficult. Dedekind is very difficult but what I’m saying here is extremely simple… So, third point: any point of the lower class, in this case the one below, any point of the lower class is below or inferior to any point of the higher class.

Fourth point: x, the cut, forms part of one or other of the two classes, class A below, class B above. You can decide for yourself whether x is part of class A or class B.

Student: How do you actually choose?

Deleuze: You choose in turn, you make the two choices, you make the two choices in turn.

Student: I see…

Deleuze: All you can say is that if it belongs to… if it belongs to class A, it doesn’t belong to class B, and vice versa, but you have no reason to choose one over the other.

Last remark: any straight line has an infinite number of cuts, or if you prefer, the series of rational numbers has an infinite number of cuts – each rational number being a cut. Okay, it’s not difficult, is it?

And this is where the marvel arises. Once again, we go from catastrophe to wonder, because Dedekind asks us a simple question. Well, okay… my straight line here, remember? It’s full of lacunae… the lacunae are the irrational numbers. In other words, my straight line has an infinite number of cuts, you see, but it’s a diabolical trick: he is in the process of defining continuity by the cut.

From then on, no more relations… in other words, he attains the great reconciliation of number and size, but at what cost? By radically changing the concept of number. That’s the mark of a great mathematician. So, I’d almost say, what’s the difference between a mathematician and a philosopher? I mean… if you accept my definition of philosophy, which I’ve always proposed, namely that it’s a discipline that consists in inventing concepts, here I’m taking an example from mathematics. Dedekind’s idea of defining numbers by the cut is a great conceptual invention in the same way as the Descartes’ Cogito is a concept. It had never been done before. Never. How was number defined before? It was defined by unit and addition, the notions of unit and addition were needed to generate the concept of number.

Student: There’s a lacuna in your… I refute the word “diabolical” in favor of “intellectual”, sorry…

Another student: Louder, please!

Deleuze: Sorry, can you repeat?

Student: I refuse the word “diabolical” in favor of the word “intellectual”!

Deleuze: Okay.

Student: Thank you!

Deleuze: Okay… but did I really say “diabolical?”

Student: Yes, you did.

Deleuze: Oh my God! It was a slip of the tongue. You see, we can’t yet see what’s so astonishing about this problem. So, it has its infinite number of cuts. Any straight line has an infinite number of cuts, but it also has an infinite number of gaps… the irrational numbers. If every rational number determines a distribution on the straight line as we’ve just seen, a distribution into two classes, well, okay. But the lacunae, the irrational numbers, are not cuts, they’re gaps. And Dedekind’s problem will be: how to give the lacuna the status of a cut. If he succeeds in giving the lacuna the status of a cut, he’s won, that is to say he’s unified all the numbers under the concept of cut. At that point, the essence of number will be the cut. And if you like, this constitutes a kind of revolution in arithmetic.

And how will he manage this? Well, let’s try to mark a gap in his schema, I return to this schema… all I have to do is take as a class, for example, a simple case: I take as a class the two classes, since a cut divides into two classes. Well, here, I take the simplest case: the number 2, and I have my two classes, 2 being considered as the cut. I therefore have my two classes, all numbers smaller than 2 and all numbers larger than 2. So, this is a cut… fine. Now, suppose I define my two classes as follows: all the numbers whose square is smaller than 2 and all the numbers whose square is greater than 2. The square root of 2 is an irrational number, it’s a gap. At the same time, if I just say that, you must already sense how he’s already reducing the lacuna to a particular case of the cut.

Because you’ll remember the condition for the rational cut, that is, the cut made… the distribution made by an integer or fractional number. Which is that any term, any term of the first class must be smaller than any term of the second, and the number that marks the cut must be included either in the lower class or in the higher class. 2 will belong to one of the two classes, if you take 2 as the cut. If 2 – the choice is purely conventional – if 2 forms part of the higher class, you’ll say that the higher class has a beginning. On the other hand, the lower class has no end. It has no end since it converges to infinity towards 2, in a convergent series. Conversely, if you consider 2 – what did I say? – yes, as the beginning, I said… first case, you consider it as the beginning of the higher class. In the second case, if you consider it as the end of the lower class, then the lower class does have an end, while the higher class has no beginning. Right.

Now, suppose you say this: let’s admit special cuts, but what’s special about them? It’s that in any rational cut, either the lower class has a maximum, or the higher class has a minimum: that’s what defines a rational cut. 2 is a rational cut because either the lower class has a maximum, which is 2 itself, or the higher class has a minimum, which is 2 itself. So, what would be an irrational cut? Well, an irrational number… produces a distribution. The square root of 2 produces a distribution in the same way rational numbers do. The square root of 2 operates a distribution on the line, meaning a distribution of two classes. It’s just that in itself it is neither part of one nor the other. It’s part of neither, so neither of them has an end, nor a beginning. In other words, there are no more lacunae, there are only cuts, given that there are two kinds of cuts.

We will call a “rational cut” one that produces a division into two series, such that one of the series has an end or the other a beginning, with the cut forming part of one of the two series. We will call an “irrational cut” a distribution in which the cut forms part of neither of the two series, such that one of the series no longer has an end just as the other no longer has a beginning. And at this point we’ll simply say that continuity is the set of rational and irrational cuts. You will have defined continuity itself by the cut. From that point on, number will indeed be reconciled with continuity, but on what condition? On condition that we change our concept. The genus of number is now the cut. If the concept of number is the cut, then reconciliation takes place between the continuity of lengths and the discontinuity of numbers, a discontinuity that was not filled by the set of rational numbers, since irrational numbers created lacunae… [Recording interrupted] [28:55]

… nothing to do, nothing to do with mathematics. So, you know, in early, let’s say pre-war cinema, what’s going on? There are cuts, in fact this is a cinematographic term. There are cuts between two images or between two series of images. These cuts come in many shapes and forms. They can be fades, with the fade itself being either to black or a cross-dissolve. They can be montage cuts – for example an optical cut, purely optical. Or they can also be… they can involve a refinement that already existed in cinema and that you already find in [Sergei] Eisenstein in some splendid cases: false continuity.

Well, this whole field, I would say… it’s odd because this cinema is already familiar with everything, it’s just a hypothesis… but couldn’t we say without forcing the analogy too much, that it operates through the rational cut? Take a dissolve, for example. In a dissolve, you have a distribution, it’s a cut because it produces a distribution between two series of images. And the cut itself is part of one of the two series, it’s typically a rational cut. I’d say that – and here I’m feeling less sure of myself, because I’m afraid people might say the opposite too, but it doesn’t matter – I’d say that in a dissolve to black, the first series has no end, and the second series has a beginning. In a cross-dissolve, I’d say the first series has an end and the second series no beginning, but I’m not sure you can’t say the opposite, too. It doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter but… Yes, it does matter. Maybe it’s both points of view, you’d have to say both at the same time, I don’t know… but I think that pre-war cinema proceeded mainly through cuts, these cuts being cuts of a rational type.[1]

So, we must, we must nonetheless… but what’s your reaction? You might say this is completely arbitrary, that I’m mixing everything up, I’m mixing up mathematics and cinema. But I myself would say that it’s a bit of an exaggeration to think that! Because it’s not me, it’s Eisenstein! There are passages in Eisenstein that everyone knows – well, that many of you know – and that aren’t just him showing off, where he explains that the constitutive images of a film correspond to a law of spiral development. And he comments frame by frame on Battleship Potemkin [1925] and, I would say… we’ll see after a much-needed morning break… I’ll try to clarify this vision. But he himself gives us the formula that the film’s development obeys, namely commensurable, meaning rational, relations, OA/OB – of the type, these relations are commensurable by nature – OA/OB, he says – it’s a formula he always goes back to – equals OB/OC… It’s the very type of rational relation that’s supposed to determine and that supposedly refers to the “golden section”, the golden section being a point, the point that he himself calls “caesura” or “break”, he calls it a caesura – grant me that, I don’t even know if there are two words in Russian for “caesura” or “break”, but it’s the same. Right, so I’m not tacking one problem onto another; I understand that it’s not a question of developing things mathematically with regard to cinema, but it’s an odd encounter nonetheless.[2]

You might tell me that this cinema is already familiar with false continuity, yes. And it’s already familiar with montage cuts, yes. The optical cut… yes, it’s true, but what are these? Lacunae, deliberate lacunae, deliberate lacunae that must have an emotional effect. Okay. I’ve been saying all along that what we’re seeking is what we might call the new characteristics of post-war cinema. I believe that, among others, and here I go back to this again… what is the novelty of [Robert] Bresson in this respect? What is the novelty of the New Wave in this respect? It’s the arrival in the image, in the cinematographic image, of a completely new type of cut, even if the cut retains its original definition, to produce a division between two series of images.

But here’s the thing: I’d say very roughly – and that’s why I needed this long mathematical excursus – I’d say very roughly that modern cinema operates or invents a whole new conception of the cut. It proceeds – not always, not always – but it proceeds by irrational cuts, that is to say, with the criterion we took from Dedekind of the irrational cut: the cut is no longer part of – it’s not as in the fade to black or the cross-dissolve – the cut is no longer part of either of the two series it divides. It can be imperceptible. In other words, false continuity takes on an absolutely new dimension. It was there before, but before it was simply a lacuna. Now its status has changed: false continuity stands for itself. It is no longer simply a gap in the series of images… it is an irrational cut between two series of images and, as such, belongs neither to one nor to the other.

You’ll tell me that this is not such a major upheaval. Yes, it is! All the problems of rhythm, if you make the comparison, correspond precisely to this discovery of irrational numbers. The cuts are equivalents of irrational numbers, whereas, in my view, the montage in old cinema, in pre-war cinema, was a type of montage that was always conceived in terms of commensurability. For Eisenstein, who was one of the greatest theorists of montage in the pre-war period, the presence of relations of commensurability as a condition of montage itself and of what he called harmony in montage seems obvious. Whereas you will see… I’m looking towards the future… and if I’ve made use of a distant parallel with mathematics, why shouldn’t we, someday in the distant future, make a similar parallel with music? You see, here too, everything I’ve just said about the notion of cuts, of series, it’s not that it would resemble or apply… but wouldn’t it have equivalents in music too? But right now, I’m only considering visual images, and I would say it’s inevitable that false continuity has taken on a completely different meaning.

False continuity in modern cinema is once again the great precursor of this notion. It’s no longer a lacuna, it’s an irrational cut, and as such, false continuity begins to stand for itself. It’s an irrational cut that is perfectly positive in itself. False continuity has taken on its maximum positivity, however small this may be, meaning however rapid it appears, however small the duration of time it occupies, and supposing it spreads out, expands. If it spreads out and expands – and we’ve already seen cases of this – it gives us the white screen or the black screen. The white screen or the black screen will be the presentation of a cut that is irrational in itself, and will react upon the whole set of images, it will operate on the whole of the distribution of the two series, but will belong to neither of the two series. And the images will be in perpetual relation to the irrational cuts that pass through them, and the white screen or the black screen will be the exposure of the irrational cut for itself.

We’ve seen the particular importance of the white screen or black screen. As [Noël] Burch said in the text I referred to last time,[3] the white screen or the black screen had appeared before, but then their value was mainly that of punctuation. That’s exactly what I’ve just said. False continuity is the equivalent… false continuity had appeared before but then it had the value of a lacuna. It’s… the terms are different, but it’s the same thing. So, Burch says, well, you can feel that there’s a certain moment with experimental cinema – not at its birth, because there’s always been experimental cinema, of course – but there’s a certain moment, in experimental cinema when the white or black screen begins to stand for something in itself, that is, it assumes what he calls a structural value. Well, I’d say that this is only possible when the black or white screen stands for the presentation of the irrational cut. We’ll have to look closely at this in experimental cinema, which has given a very important role to the white screen and to the black screen, even though this is susceptible to variation: white on white, etc., and has undergone adventures analogous or equivalent to those which occurred in painting.

Among modern filmmakers, I mentioned [Philippe] Garrel as one who gives particular importance to the white or black screen. And here it’s not even a structural importance, it’s a genetic one. In his films, the black and white screen takes on a genetic, and not simply a structural, value in relation to the image. Now, in this case I’d say that exactly the same thing applies, it’s a cinema based on irrational cuts. The irrational cut would have two figures: false continuity at the limit of perceptibility and the white screen or black screen and their derivatives – I mean the bluish screen, the snowy screen, the overexposed screen, the underexposed screen, everything we looked at a little before – it’s a cinema… in this sense, it’s a new type of cinema.[4]

So, what have I just confirmed in saying all this? I’ve just confirmed the following idea – you see, we could go even further… As I said, the mutation of thought that I was looking for in Blanchot and Foucault had two major characteristics: it was the thought from Outside, thought that claimed to be that mysterious instance, the Outside, which we saw was not the external world, and that the Outside lay well beyond the external world. As I was saying, it’s a thought from Outside that reveals itself in thought as the interstice… so the interstice begins to have value in itself.

I’d say that the cinematographic image not only verifies but invents a completely analogous mutation on its own part, insofar as false continuity in modern cinema has become an irrational cut which is the interstice, that is to say it’s no longer part of either one or the other. False continuity is no longer part of either of the two series of images it separates. In this sense, it constitutes an irrational cut. So, we have the interstice. Second notion: presentation of the augmented interstice, the white or black screen that I would call the presentation of the image’s Outside, the presentation of the Outside or of an Outside of the image or of a reversal of the image.

So, the two fundamental aspects we have found in the image of thought – the Outside and the interstice, the Outside presenting itself in the interstice – find their correlate in the cinematographic image in terms of false continuity and interstice, its development in the black or white screen and the correlation of the black or white screen with false continuity conceived as an interstice, meaning as an irrational cut. If things were like that, it would suit us well. Would you like a little break? Yes? Let’s have a short break. You think about it, and then you can tell me… Oh no, sorry, before we take a break, did you want to say something?

Student: [Indistinct words] … in the ’30s…

Deleuze: Yes.

Student: [Indistinct words]

Deleuze: Yeah…

Student: [Indistinct words]

Deleuze: This time there’s a point, a white point then?

The student: [Inaudible words]

Deleuze: That’s right, that’s right… but then I don’t know what you make of it. For me, it’s part of… it’s part of the great tradition of abstract cinema, for me it’s the old regime of abstract cinema…

Student: [Indistinct words] … actually I don’t know if it’s a rational or irrational cut, but it’s a very strange cut in any case. It’s a cut that, in a certain way, one could say, there’s a link… well, I mean according to classical criteria, one could say there’s a single plane, there’s a single image… in any case, I don’t know, there’s a single point.

Deleuze: There’s an alternation between two series, but we’ll see that later. I’d very much like

to try to periodize abstract cinema, and I’ll need your help with that… because, for me, to say it very quickly, in experimental cinema the real cuts or the real equivalents of irrational cuts only appeared with the methods of flickering.[5] It seems to me that there would be a big difference in terms of, what’s his name… Norman McLaren, isn’t it? It’s with McLaren that we really move on to irrational cuts. But we’ll talk about that later. Let’s see. Let’s see… [Recording interrupted; 48:44]

… I’d like to finish up this point before you speak. I would say, if we were to try… if we were to try to better define the character of a possible difference between pre-war and post-war, from the perspective, this time, of the procession of cinematographic images, couldn’t we say something like this? I say “something like this” because, obviously, we would badly need to qualify it better. Once again, it’s not post-war cinema that invents false continuity. It’s the whole… no, it’s something more complicated than that.

But let me return to the example of Eisenstein. I’m referring to the classic text, the great text Non-indifferent Nature[6] and to his very detailed commentary on Battleship Potemkin – these very famous passages… So, what do I see in it? I see the idea that images develop along a spiral, and that this spiral, a logarithmic spiral, an open spiral, and should I read… You see, I’m fed up with making drawings, here I would have to make an axis and then a spiral, it’s difficult to draw, very difficult to make, you see… you draw an axis, like that, and then you make a spiral from a point… Well, anyway, you can find all this in the chapter “Organic unity and pathos”.[7]

So, I’m reading from page 16… “Logarithmic spirals are varied, but they all have the same feature, that the consecutive vectors arranged as OA…” – where O is the point of origin of the spiral and A is the cut with the axis… – “the consecutive vectors arranged as OA, OB, OC, OD etc., in the sketch form a geometric progression, that is, for the logarithmic spiral, the following series will always occur: OA / OB = OB / OC = OC / OD, etc. = small n”. So, you get the impression that Eisenstein’s exaggerating here, but then you think: no. I mean, he didn’t apply all this, but it’s true that the way he conceives a film is – and he shows it very well in the case of Battleship Potemkin – the way he conceives a film is like this: he requires a caesura. He needs a spiral development and a caesura, meaning a break or cut. His problem is to choose the cut. He himself says that there’s a major break in Battleship Potemkin. And that break is the transition from water to the earth and death, where we go from the battleship to mourning on land. For him, this is the great break, the passage from water to land. In fact, the break is multiple, it concerns the elements, it concerns dynamism, it concerns matter, it concerns form and so on. So, you have a spiral development and a caesura.

Then he’ll show that each of the vectors of the spiral, meaning the different parts, themselves have cuts. And as he says, the cut can’t be at the halfway point, that would make for extremely tiresome symmetries. But they are at the famous point – it’s a point – at the point of the “golden section”. I don’t have time to go over all that again… you’ll see, it’s part of the great passages of “Organic unity and pathos”. So, you see, we have three fundamental notions: the spiral, the determination of a major break-caesura, and the different parts on either side of the series, which makes two large series, and in the first series… in the previous series just like in one that follows we once again have sub-caesuras, sub-breaks.

Now, the law of the type O/A = O/B… no, sorry, OA/OB = OB/OC, etc., meaning that the smallest part must be to the average what the average is to the Whole, seems to me an excellent definition of the commensurable relation. And in the same way, I’d say the caesuras, the “golden sections” constitute an excellent presentation of what in mathematics – since he’s invoking mathematics – of what in mathematics we refer to as rational cuts.

So, I’d say, to connect this with what we were doing last year, that a cinema that distributes series of images according to commensurable relationships and rational points is precisely a cinema of the movement-image that gives us an indirect representation of time. I don’t want to go into that now, as it’s no longer our subject. It’s just to make a connection with what we were doing last year… and once again, Eisenstein, notably in Ivan the Terrible [1944], was able to come up with a technique of false continuity, for example, in the door scene, in the famous door scene where there are some marvelous examples of false continuity, or a technique of false continuity like… but in any case, it was already completely present. However, this doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have the same function, that false continuity effectively plays the role of lacunae. In other words, there are gaps that must be crossed, that the procession of images must cross by leaping over them.

Whereas if I try to define modern cinema, I’d say, well, in one sense, nothing has changed, but in another sense, everything has changed. Why is this? Because here, it’s as if the gaps are no longer subordinate to the linkage of images. It’s the other way round. It’s the linkage of images that is now subordinated to the gaps, so that the only form of linkage left is what the gaps allow, or what amounts to the same thing, I could say that this is a cinema where there are no more lacunae to speak of, there are only irrational cuts.

But here there is a misunderstanding… I mean, I don’t know Russian, but it’s obvious that there’s been a mistake in the translation, because the translator didn’t pay enough attention to mathematics. I’d like to point out that it’s page – which I found very surprising – it’s page… where is it… a very shocking misunderstanding because… Here it is: “Expressed by whole numbers,” – you see, here we find everything we have said so far regarding rational numbers – “Expressed by whole numbers, the proportion of the distance of the point of the golden section from the ends of the segment is expressed in sequential approximations by the following series: 2/3, 3/4, 8/13, 13/21 etc., or the [incommensurable] fraction 0.618 for the greater segment, considering the whole as a unit” – and this is the very definition of the golden section. But clearly, the “incommensurable fraction” is a nonsense, for one simple reason: there is no such thing as an incommensurable fraction.[8] The incommensurable, the incommensurable ratio is expressed in an irrational number, which is to say a non-fractional number – meaning that there is no such thing as a fractional number. On the other hand, the right word for a fraction would be “irreducible fraction”. 2/3, for example, is an irreducible fraction, since it can be expressed neither as a whole number, nor as a finite number with a decimal point. So, it’s an irreducible fraction, expressed as 2/3. But to speak of an incommensurable fraction is… I mean, it’s a misunderstanding, not irksome for the understanding of the page, but annoying for the French translation.

So, I would say that when the lacunae – it’s the same thing – when the lacunae subordinate association, when the lacunae subordinate the linkage of images, that is, when all that remains of the linkage is what the lacuna permits, then the lacuna is no longer simply a gap. It has ceased to be a gap and has become an irrational cut, an irrational cut that stands for itself, and it’s precisely because it stands for itself in the augmented form of the black screen or the white screen, that it now subordinates associations and image linkages. We’ve left linkages behind. All that will remain of the linkages is what the cuts allow.

That’s why, as I said, Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar [1966] seems to me a brilliant film, a great film in this respect. The few, the localized linkages… there are only very localized linkages, very localized linkages that are distributed by irrational cuts, by the play of irrational cuts. And it’s obvious that these irrational cuts expand and stand for themselves, assuming a structural value, or a genetic value, in the form of the intrinsic value of the white screen or the black screen.

And indeed, let me finish on this point… the two are equally interesting: the imperceptible use of the irrational cut, meaning the rapid false continuity where the use of magnified perception in the form of the black screen and the white screen are completely…. and then all the transitions between the two… are completely… completely complementary, even if it’s not the same authors who privilege one or the other. Take the Godard method. The Godard method, it seems to me, in many films, and we’ll have a chance to come back to this – once again, it’s just part of the program we’re putting together – the Godard method consists in, as I was saying, breaking the linkage of images. It consists in saying, in the typical Godard manner, you understand, you are spectators, you’re on the assembly line [à la chaine] because the images themselves are on the assembly line and as long as this is the case, you’re on the assembly line. So, we’re all working on the assembly line. Cinema is made on the assembly line, and the spectator too works on the assembly line. Well, you can see Godard’s brilliant elaborations on this – we’re all S.O.[9] We’re all, well, cinema is a job, okay. And in Ici et ailleurs, he announces a de-linkage that will liberate both spectator and image. [Recording interrupted] [1:03:13]

Part 3

… how does he do it? I mean… I’m saying that what counts in modern cinema is in a way the interstices, in the form of false continuity, irrational cuts, irrational dots, or in the form of the white screen or black screen, which stand for themselves. Again, think of the importance of the plumy screen in [Alain] Resnais’s last film, L’Amour à mort [1984], and how much value it has in its own right, meaning at every moment when a sequence could be made in the story, he inserts this fluttering screen, his black screen with its fluttering grains, fluttering little feathers, fluttering electrons, and this is the moment when the music enters, which will precisely break the linkage of sequences. So, the only remaining link will be that between the two deaths, the apparent death and the real death of the character that I mentioned last time, because in Resnais everything always occurs between two deaths.

Now, you could always object that there are only interstices in relation to existing linkages. But that’s not true. I mean, the interstice ceases to be subordinate to the association of images. That’s what I think is so important. When the interstice begins to stand for itself, either as an irrational cut or as a black-and-white screen… then the linkage of images takes second place. The images are really unlinked, and there remain only localized linkages, a law for which we still need to discover. Perhaps we’ll begin to see what this law is next time. I’d say that these are – I’m saying it in advance like this, to engage those who know something about it – I’d have to say that they’re linkages for which there’s a word that exists in physics, mathematics and probability calculus: they’re “semi-random linkages”. “Semi-random” is a very peculiar expression and is exactly what we call “Markov chains”, after another famous author, [Andrei] Markov, who studied this type of linkage. These are linkages, we could call them fragmentations, they form a kind of “re-linked fragmentation”. The linkage is never direct: there are operations of re-linking through cutting, and this is what explains the reversal of relations, it’s precisely a re-linked fragmentation. There’s no linkage, there is only re-linkage. But we’ll try to understand this more precisely. That’ll give us more mathematics to do, which is good.[10]

So, I would ask, regarding Godard’s method, how does he actually obtain his de-linkages? Here, I’ll take a case that caused a scandal, a case that provoked a great deal of outrage in Ici et ailleurs: the bringing together of two images, the image of Golda Meir and the image of Hitler. And here, indeed… and whatever the… whatever their views on Israel’s policies, the way Godard in Ici et ailleurs brings together and links Golda Meir and Hitler, had something that for many viewers was truly intolerable. In a way, I’d say, it’s – and this is the same problem as… – it’s because we don’t sufficiently know how to read images. It’s because we’re content just to see an image. If we simply look at it, then there is indeed something almost intolerable. But if we read it, what does this imply? It implies taking into account everything I’ve just said, the image becomes legible. I’d say the old image was visible, but the new image is perhaps, in a way, readable. But what would this mean?[11]

This rapprochement would be intolerable if it were simply an association that crossed an interstice. If it were an association, even if this association leapt over a small gap between the two, there would be something hard about it. But it’s obvious that in the case of Golda Meir and Hitler, Godard is making a deliberate provocation. Yet to understand this deliberate provocation you have to understand how he proceeds in other cases when there is no provocation. He’s not at all seeking two similar or contiguous images to link together. If you link images by resemblance or contiguity, it’s clear that the cut will be subordinate to the association, meaning that even if there is a cut, the linkage of images overleaps it. The cut is the minimum condition for the image procession, the association to take place. That isn’t what Godard is seeking. When he takes an image – he doesn’t hide his method, it’s very concrete – when he takes an image, he asks himself what other image he might connect it with. And what would that be? Another similar image? Absolutely not. In other words, difference is everything. Remember the great texts by [Claude] Lévi-Strauss, where he says how we’ve always believed that resemblance is primary in relation to difference, when difference is primary in relation to resemblance, a structure is a distribution of difference, and so on and so forth… Okay.

But given an image, Godard asks himself: what other image am I going to relate it to, the conditions being neither those of contiguity nor those of resemblance? So, what are the conditions if it’s neither a question of contiguity nor resemblance – which is to say the associations we talked about earlier that were part of the old image of thought? You’ll recall that association by contiguity and association by resemblance formed part of the old image of thought. This is going to be something very different. It’s going to be something like conditions of… what in physics we call “disappearance”. Disappearance, that is, choosing another dissimilar, distant image – so there is neither resemblance nor contiguity – in such a way that, between the two, something happens… You see, this implies a choice, in other words, it implies an act of creation. I have an image, I do my utmost to look for another image, so this can fail in two ways. The first way, according to Godard’s method, would be to fall back into a simple association, to choose another image that would be similar or contiguous. The second way would be to choose any random image. That’s why Markov chains aren’t completely random, they’re semi-random, only semi-fortuitous or however you wish to call them.

So, the other way to fail is where I choose any other random image. There’s not much chance of anything happening between the two. I mean, it’s a bit, let’s say… and not even that, you can’t say that the Surrealists… I think the Surrealists remained very faithful to association. But still, in their way of choosing by chance… because one could conceive of random choices of a Surrealist type. But then what happens between the two images if I draw them at random? There’s very little chance of a phenomenon… to use a term from physics, there’s very little chance of a resonance-type phenomenon occurring. So, the Godardian question would be how to choose another image that is different and distant, according to two anti-associative conditions, the two conditions of de-linkage, an image different and distant in such a way that something nonetheless happens between the two, between the two. This is the between method.

So, in Ici et ailleurs, what do we have? The images he chooses are the group of fedayeen… The film will come out, I don’t know how long afterwards… ten years later, and it’s all about these fedayeen you may or not have heard of, these fedayeen who are now dead and so on.[12] And the other image he will choose is that of a French couple, ten years on, in their relation with TV, in their relation with cooking, in their relation with love and so on. So, there’s a lot going on. Something has to happen between the two, something literally has to be revealed between the two, in this bizarre confrontation, which operates neither by resemblance nor by contiguity, something that belongs neither to the first image nor to the second. This is the Godard method in its essence. It appears… it appears in its pure state, if you like, at least twice, in Ici et ailleurs on the one hand, and on the other, in Six fois deux. But it’s present in all his work.

You see, it’s no longer a linkage of images. In fact, it’s a cinema that no longer links images together. Why is this? Because it proceeds by irrational cuts. It proceeds by incommensurables. I’d say the two images are incommensurable. The image of the fedayeen and the image of the little French couple are two incommensurable images. Between the two, there is really a cut… it’s an irrational cut in its pure state.

And the fact that Godard is very conscious of the problem of the cut is something you’ll find in Sauve qui peut (la vie) [1980], where we find the famous freeze-frames, stopped motion. Where does the caress end and the slap begin? And there’s a wonderful sequence where… where the hero approaches the heroine, extends his arm… so, where does the caress begin, no… sorry, where does the caress end and the slap begin? You see that here, it seems to me, in this operation, he is reflecting on his cinema at the same moment that he makes it… I can’t say this is abstract reflection since all his images are constructed in this way. Likewise, if you recall the decomposition of pornographic attitudes in Sauve qui peut (la vie), in the porn episode, in the porn episode the decomposition, which is firstly a visual decomposition of body attitudes, and then a sonic decomposition of sounds, a decomposition of phonemes… well, the processes of decomposition are constant.

So, where does the caress end and the slap begin? We can understand this precisely in terms of the Dedekind diagram that we looked at earlier. If there were a rational cut, we could say, the caress ends at such-and-such a moment, or else say that the slap begins at such-and-such a moment. But Godard isn’t interested in this. What interests him is what happens between the caress and the slap. The irrational cut, he wants to capture this irrational cut, this “between the caress and the slap”, which belongs neither to the series of the caress… neither as the end point of the caress, nor the starting point of the slap. In other words, given two images, a third will emerge that pertains neither… no, sorry, given two series of images, a third will arise between the two that exists for itself and belongs neither to the first nor to the second series. So, here we have a process that literally… a process that delinks images.

And so, if you like, this is the interstice, this is the interstice, and also the reversal. Once again, when the interstice designates an irrational cut, it is no longer at the service of the linkage of images in the manner of a dissolve. On the contrary, it is the linkage of images that disappears in favor of the interstice, or at least all that remains of linkage is a re-linking, without there even having been a primary linkage. There can only be a re-linkage that is distributed by the interstice. And from then on, it’s the natural vocation – though not in the case of Godard – but it’s as though the natural vocation of the interstice thus understood is to develop into a white screen or a black screen.

And I’d reiterate, to sum all this up, that the white screen or the black screen is actually the force of the Outside, the Outside or the reverse of the image, just as the cut, the irrational cut, is the interstice, and the force of the Outside manifests itself in the interstice. This is the fundamental notion both of the cinematographic image and of the image of thought. So, we’re done with this third mutation, since what we’ve been doing up until now has been to confront certain mutations of the image, both the image of thought and the cinematographic image, on three levels. And our three levels were: first level, substitution of belief for knowledge; second level, Give me a body; third level, the thought from Outside.

Now we’ve almost completed our task. We just have a fourth, a fourth mutation to look at, a fourth mutation. This fourth mutation – but I’m going to stop right now because I’d like you to react… this fourth mutation is something we’ve already anticipated. It’s what we… So instead of imposing mathematics on you, I’m going to impose something else on you that’s no more fun: Give me a brain. Give me a brain. Give me a brain… you understand? What does it mean, what could it mean, if I took this as the formula for a radical change, both in the cinematographic image and in the image of thought?

Give me a brain, then would be similar to how it is for the body, I told you, that it’s clearly similar when we say, give me a body. And as this doesn’t mean, give me a nice body, so too, give me a brain doesn’t mean, give me a beautiful brain. So, then what does it mean, because a brain is something we already have, we don’t need another, okay, we don’t need another one. Just as we already have a body, and we don’t need any other. Yes, but, after all, we needed Blanchot to be able to discover something about this body, and maybe, as [Søren] Kierkegaard said, give me a body meant, put a thorn in my flesh. So, what does Give me a brain mean, and what would we put in the brain?

You can see why it all links together. If I didn’t have this fourth formula, “Give me a brain”, you might have told me straight away that something was missing. Because if there’s a place, if there’s an organ where the problems of the cut, where the strange problems of the cut, arise… it’s easy to say that it enters the brain and then leaves the brain the same way. Take reflexes, for example. You have the sensory message; it passes into the brain and then it triggers an act, it triggers a motor movement, okay. But what happens in between the two things? What happens in the brain? Give me a brain, what does that mean? Well, it means that maybe two things have changed here too, this time between the wars, not because of the war, or yes, maybe the war did have something to do with it. I have the impression of two things having occurred, and I don’t think we should ever look to see what was at the forefront of this. Was it painting? Was it music? Was it science? Given the complexity of things, you never know where it began.

But I have the feeling of two things, that scientists, that neuroscience has developed so rapidly since the war that science now proposes brain models of a completely different nature. All this is very much linked to the problem of the automaton. So, we’ll again see… – and all this goes very well with the problems we’ve already looked at – that they are of a different nature, that there are brain schemas today, models of the brain that should make us shudder. Why? Because of the coefficients of uncertainty, not of knowledge, but crazy uncertainty coefficients that affect cerebral operations. I mean, the way in which the brain can no longer be thought of in a so-called deterministic way, but where we have to appeal to probabilistic, or worse still, random patterns in the reception and communication of a message, all of which make our impression of the brain increasingly fragile. And when I say increasingly fragile, I mean, it’s like a thorn in the flesh. Give me a body, maybe that meant: my body has to have its thorn. But give me a brain, maybe this means that sooner or later, I will have to realize that the brain is the most fragile, the most aleatory of all my organs.

Does science tell us this? Perhaps it does. But it’s not science, it’s not science that we apply, when we think about our brain. We have certain relations with our… each of us has a relation with their brain, just as we have a relation with our body. That’s what I want to talk about, the relation we have with the brain. Not only do we have neuroscience – and when I say “we”, I mean those who practice it for us, the brain specialists – but independently of them, we experience our own relation with our brains in a certain way.

In the same way, I would say that – not to confuse things – it isn’t science that has modified the lived relation we have with our brain. In my view, and here I’m making a major contribution to the problem of cross-generational incomprehension, I have the strong feeling that we no longer live, that we no longer live our relation with our brain, with our own personal brain, in the same way as people did, say, 50 years ago or 100 years ago. Not only have scientific schemas and models changed… but it’s not because of the application of science, it’s that the same time, and in another sense, our lived relation with our brain has changed. Perhaps we don’t expect the same things, we expect different things, that’s what I mean by lived relation. Here too, tiredness and waiting have become cerebral. Do we have the same forms of tiredness and waiting? What is our lived relation with the brain? Just as before I was trying to say: What is our lived relation with the body?

So perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that, just as after the war there arose a cinema of the body – which I tried to comment on while I was explaining the formula: Give me a body, then – so too, post-war cinema came up with a new cinema of the brain. There has always been a cinema of the brain, and in my view, this has been one of the great contributions of what is called experimental cinema… and experimental cinema has existed since the very birth of cinema. But the question is, rather: isn’t there a cinema of the brain that assumed an entirely new form after the war?

You see, our problem is once again threefold: cerebral models, our lived relation with the brain, and the possibility of a modern cinema of the brain. And if I wanted to make some facile symmetries here, while tracing a history of cinema, everything would be fine, everything would work out perfectly, because for the cinema of the body, I took an American – there are others – but I took an American because he seemed a particularly brilliant example, and this was [John] Cassavetes. And if you remember I said, this is a cinema of bodies, of attitude and gest, where all space is subordinated to attitude and gest. And then I said, on the other hand, we had the Nouvelle Vague, where Godard and Rivette were making a cinema of the body, once again based on attitude and gest, reducing space to the linkage of attitudes in this gest.

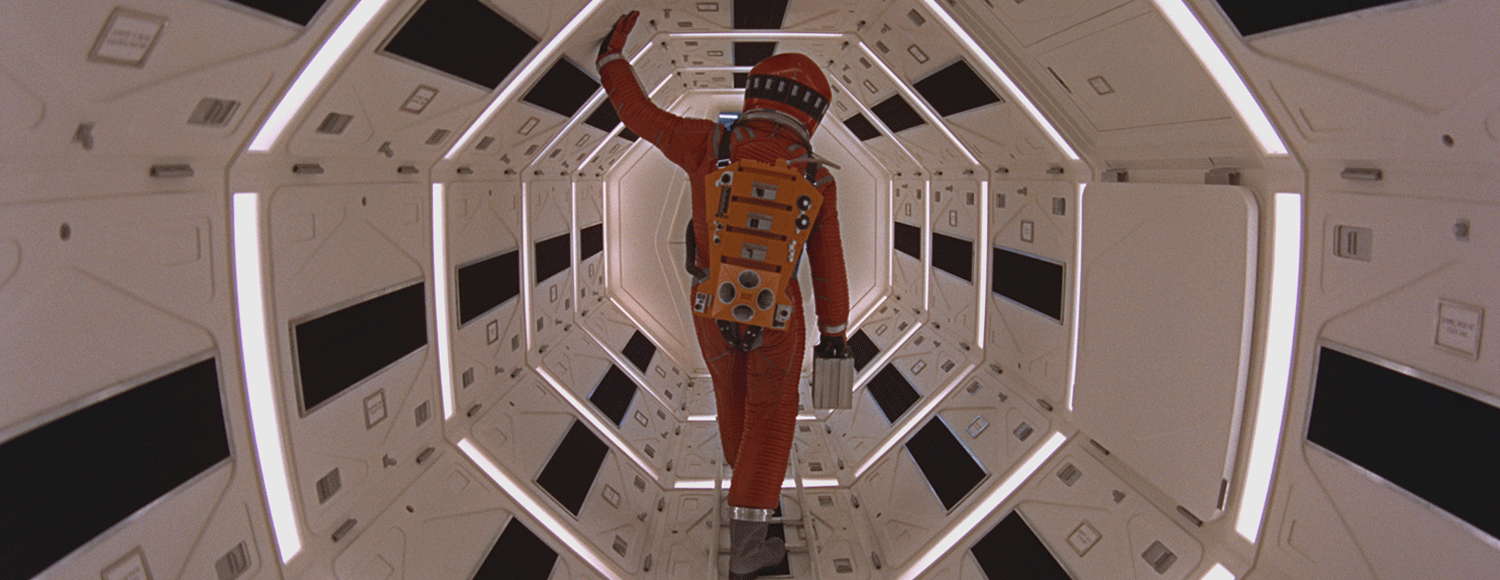

For a great cinema of the brain, I think that here too we would need to summon both an American and a French filmmaker – that would be perfect – only as examples, of course, since there are many others. But I’d say, yes, there is one American filmmaker in the history of cinema, of a cinema of the brain, a cinema that presents the brain as a world. In American cinema, there’s one figure who has attained precisely this brain-world… and that’s [Stanley] Kubrick. It’s undoubtedly Kubrick. What a conception of the brain, what an image, what a cinematographic image of the brain! Given that by cinematographic image of the brain, I don’t mean filming a brain… any more than by cinema of bodies, I meant simply filming a body. It may involve that… it may involve that. But obviously, that’s not what is at stake. It’s the world as brain, the brain as world. And this is Kubrick’s cinema.

And then in France, a filmmaker who has nothing, who has absolutely nothing in common with Kubrick, but who strangely enough seems to me to be undertaking the same project, though he will go about it in a completely different manner – and we’ve already spoken about him a little – and this is Resnais. With Resnais, the world-brain, the brain as world and the world as brain become the supreme object of cinema. Take Toute la mémoire du monde [All the Memory in the World, 1956], for example. What is it? It’s the Bibliothèque Nationale as a world, but in terms of each element in the Bibliothèque Nationale… there’s a very good critic of Resnais, a very good commentator, called [Gaston] Bounoure, who says that the man pushing the book-laden trolley behaves in the exact same way as a neuronal messenger, in Resnais’s film, he’s just like a neuronal messenger. In other words, the national library is a world, and it’s also a brain, it’s a brain and it’s also a world. I mean, it’s a brain-world film.

Well, in Resnais, it’s clear that cerebral processes – and he’s always said that this the only thing that really interests him – he’s always said that what interests him is what happens in the brain, or what happens in thought. If he took on [Henri] Laborit as a collaborator for Mon oncle d’Amérique [1980], it was explicitly not to present a theory – Laborit takes care of this, of elaborating a theory of the brain – but to make a cinema of the brain. In the case of Stavisky [1974], one of Resnais’s finest films, which was so poorly received by the public, Resnais explains that Stavisky is completely unbalanced because he lives with his two cerebral hemispheres unsynchronized.

Now this should interest us, because I’m speaking about a lived relation with the brain. Contrariwise to how things were in the past, have we kept our two cerebral hemispheres in sync? Do they work synchronously? Won’t a new cinema of the brain teach us what we already secretly knew: that the two halves of the brain are not at all synchronous? And what happens when they don’t work in sync? Does this give us the misfortunes and at the same time the splendors of the swindler Stavisky and his end, and his uncertain end, his end the nature of which we have no idea? Okay.

Two non-synchronous halves, that’s an idea that ignites Resnais’ enthusiasm. If I wanted to make a simple comparison, it’s clear that Resnais and Godard, for example, are not interested in the same problem. Godard is extremely interested in thought. Yet… both of them are great thinker-filmmakers, but I’d say that for Godard, the brain is dependent on the body. And we cannot say who is right and who’s wrong. What does it matter? It doesn’t mean a thing. For Resnais, the body is an outgrowth of the brain. It’s not that one is more abstract than the other, it’s not a question of abstract versus concrete, because in the brain there’s just as much passion as there is in the body. The brain is not a rational process. I mean, it’s not a rational system. The world isn’t rational, but then neither is the brain. So, it’s not an exquisite logic that characterizes the world-brain. It’s a place of passions. You have… in your brain you have centers, but are they really centers? It’s doubtful that they are centers, but you have impulses of jealousy… impulses of jealousy, murder, death, you have suicidal impulses and so on, which animate the brain-world as much as they animate the body.

So, I would say that there’s no real difference at all in… But it seems clear to me that they’re not interested at all… and so they make a very different kind of cinema. On the one hand, it’s a cinema of the body, of body attitudes, of the gest that link body attitudes; on the other, it’s a cinema of feelings rooted in the brain, and the connections between these feelings, the cerebral connections between these feelings. What goes on in the brain? Well, that is the problem, that’s Resnais’s problem. So, the point we’re at now, we’re going to stop. Listen, yes… I’ll explain. It’s this last point we have left, so we can finish constructing our program.

Next time, we’ll have to begin to unravel what might have been – also in terms of science, between the pre-war and post-war period – the great change in the scientific conception of the brain. We must try to do this, just as simply, if you like, as we did earlier with the Pythagorean theorem. We’ll have to identify the major axes that have changed and that no longer pose the problem in the same way. Such as neurobiology. And for very simple reasons… and then, independently of this, we must ask ourselves how we live our relation with the brain, and with the fragility of the brain that there is today. I have the feeling that we’ve become conscious – and this isn’t a sign of progress – we have become conscious of the brain’s fragility which, alas, discourages many of us from thinking because we tell ourselves that… but which is a phenomenon that…

I’m very struck how in psychological studies of the body, this never comes up, as far as I know. Even at the time of existentialism… [Maurice] Merleau-Ponty spoke so extensively about the lived body and so on, but as for the lived relationship with the brain, he never said a word about it. In my view, the lived relation we have with the brain constitutes a very… an extremely profound determination of our relation with the body, one that generates both joy and anguish. That’s something we’ll have to look into.

So, what I’d like you to do for the next time is to think about all of this, since we’re coming to the end of building our program, because I’d like to hear you speak about it too, and see how you might complete it… how you can take up again these first three mutations that should still be fresh in your mind: that of belief, that of the body and that of the Outside, always given that we still have the fourth mutation to deal with, that of the brain. So, if you have any questions you want to ask about the first three, we can start from there, and then tackle the fourth mutation, which will be the last.

Notes

[1] This discussion and the one that follows on Eisenstein can be found succinctly in The Time-Image, pp. 213-214.

[2] On Eisenstein’s formula, see The Time-Image, p. 319, Note 37, and also The Movement-Image, pp. 33-35.

[3] See previous session, Praxis du cinéma (Paris: Gallimard, 1969).

[4] On the black-and-white screen, Burch and Garrel, see The Time-Image, pp. 200-202.

[5] On flickering, see sessions 7 and 8 of Cinema 1 seminar, January 19th and 26th 1982, and session 7 of Cinema 2 seminar, January 11th 1983. See also The Time-Image, p. 215.

[6] Sergei Eisenstein, The Non-indifferent Nature, trans. Herbert Marshall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

[7] This is a section from Volume I of Non-indifferent nature. See The Time-Image, p. 319, Note 37. On “non-indifferent nature”, see also pp. 159-160; pp. 161-162; p. 226.

[8] Here we have placed the mistaken word “incommensurable” in brackets, since the English translation, which uses the term “infinite fraction”, is correct.

[9] An acronym with many possibilities, perhaps simply “sans objet”.

[10] For these terms, see The Time-Image, p. 319, note 36, where Deleuze writes Markov “Markoff”.

[11] On this image in Ici et ailleurs and the interpretation of images, see The Time-Image, p. 179.

[12] Ici et Ailleurs (1976), which Godard made with his partner Anne-Marie Miéville, is in part a critical reevaluation of Jusqu’à la victoire (1971), an earlier film project, never completed, on the Palestinian struggle that Godard attempted to make with Jean-Pierre Gorin, Gerard Martin, Nathalie Billard et Armand Marco as the Dziga Vertov Group.

French Transcript

Gilles Deleuze

Sur Cinéma et Pensée, 1984-1985

5ème séance, 27 novembre 1984 (cours 71)

Transcription : La voix de Deleuze, [Partie 1, non disponible], Flavien Pac (2ème partie) et Sabine Mazé (3ème partie); révisions supplémentaires à la transcription et l’horodatage, Charles J. Stivale

[Cette séance commence clairement in medias res, avec Deleuze en pleine discussion d’un dessin géométrique au tableau, un examen de « l’histoire du théorème de Pythagore », comme il indique à la fin de la séance. Étant donné cette ouverture, et aussi la longueur réduite de l’ensemble (les deux parties, 97 minutes, étant plus courtes par un tiers que les séances habituelles), il est bien raisonnable de conclure que la cassette du début manque à cette séance.]

Partie 1 [segment non disponible]

Partie 2

… la distance entre ces points diminuant, et tombant en dessous de toute longueur, si petite soit-elle. Il n’y a, il n’y a de la place pour rien, là. Vous avez votre série infinie compacte et convergente de points rationnels. Ben il n’y a plus de place, il n’y a plus de place. Et ben, voilà. Écoutez bien, regardez, [Deleuze se déplace vers le tableau] je vais vous faire surgir une place. [Pause]

Je construis sur ma droite là, vous voyez, je construis [1 :00] un triangle rectangle isocèle. [Pause ; Deleuze dessine au tableau] Et donc ma droite, mon segment de droite, 1, avec tous ces points, tous ces points rationnels marqués par des nombres fractionnaires formant une série compacte convergente infinie dont la limite est 1. Je construis mon triangle rectangle isocèle, [2 :00] bien. Et j’appelle X les côtés du rectangle. Je prends mon compas [Pause] — là c’est un arc de cercle — je prends mon compas [Pause] qui fait, comment dire, je marque le point où mon cercle rencontre la droite AB, et vous voyez mon cercle [3 :00] a comme centre A et comme rayon le côté du triangle rectangle que j’ai construit sur la droite. Voilà, regardez, juste.

Vous vous rappelez ce qu’on vient de voir avec le théorème de Pythagore, où j’ai 1 au carré = 2×2, x au carré + x au carré, on retrouve notre théorème de Pythagore. Ce point, là, [Deleuze tape le tableau] c’est un nombre irrationnel ; c’est quelque chose de formidable, mais d’incroyable, [4 :00] d’incroyable ! Mon segment que je croyais compact, convergent, c’est-à-dire excluant toute lacune, voilà un point qui n’en fait pas partie. Il n’en fait pas partie, c’est un nombre irrationnel. Avec votre histoire : 2/3, 3/4, 4/5, 5/6, etc., etc., etc., et des quantités de plus en plus petites qui tombaient en dessous de toute longueur assignable, vous étiez en droit d’avoir constitué une série sans lacune. Voilà, voilà une lacune. Vous comprenez ? Il faut que vous passiez très vite en imagination, dans votre esprit, d’une figure à l’autre. Là j’ai mon [5 :00] segment AB ; vous le prenez tout seul dans l’esprit, vous le comblez entièrement, à l’infini, avec votre série convergente à l’infini. Et vous vous dites, ouf, j’ai du continu.

Si vous en restez là, en effet, vous ne pouvez pas voir. Je veux dire voir par l’œil de l’esprit, on n’en est plus aux sens. Votre œil de l’esprit, au sens où Spinoza dit : « les démonstrations sont les yeux de l’âme », ben, votre œil de l’esprit saisit une continuité parfaite. Vous construisez votre triangle rectangle sur le segment, vous prenez votre compas et vous faites [6 :00] surgir, quoi ? Une lacune. Il y avait une lacune que votre œil de l’esprit ne pouvait pas voir. Je veux dire là, ce n’est pas un problème de l’imperfection des sens. On est en plein dans un paradoxe fondamental, qui est une imperfection de l’esprit comme tel. Il n’est pas apte à voir une lacune sur une ligne droite.

Je veux dire, sentez, ça devient passionnant, enfin je ne sais pas, pour moi. Cette ligne est pleine de trous ; cette ligne droite que vous avez tracée, elle est pleine de trous, non pas du tout en fonction d’une imperfection sensible parce que c’est une ligne à tracés sensibles. C’est en tant qu’intelligible, que cette ligne droite constituée comme série compacte et convergente [7 :00] est en fait une ligne pleine de trous. Elle est remplie de lacunes, et à chacune de ces lacunes correspond quoi ? Correspond un nombre irrationnel qui, en effet, un nombre qui n’est ni entier ni fractionnaire. C’est une merveille, vous savez. Vous vous sentez émerveillé ? Vous comprenez encore une fois, il n’y a rien d’étonnant, j’assiste beaucoup là-dessus, il n’y aurait absolument rien d’étonnant s’il s’agissait de la ligne droite sensible, mais pas du tout. Je parle de la ligne intelligible telle qu’elle est visée par l’esprit à travers le dessin sensible.

Un étudiant : Ben là, tout change, en fait. [8 :00]

Deleuze : Quoi ?

Un étudiant : Je ne sais pas comment le dire, exactement pourquoi, si cette ligne considérée comme ligne de l’esprit et que celle-ci sur le tableau, n’est qu’une figure ou le prétexte pour montrer ce qui se passe intérieurement, il me semble que le discours se change complètement…

Deleuze : Ben, le discours n’aurait strictement aucun sens, si je parlais de la ligne sensible. Si je vous disais : je trace une ligne, et au niveau du microscope, vous verriez que cette ligne, ben, saute et que votre craie n’est pas répartie également, etc., aucun intérêt. C’est dans la mesure où la ligne droite est susceptible d’une définition dite intelligible ou purement conceptuelle, que les choses deviennent intéressantes. Si cette [9 :00] ligne définie, purement conceptuellement, est définie de telle manière ? Par la série compacte et convergente, qui me semble, qui semble donner un concept de continuité inattaquable. Et voilà que vous êtes capable de montrer que cette ligne constituée par une série compacte et convergente, est pleine de lacunes et pleine à la lettre de trous, c’est-à-dire de points qui ne sont pas rationnels, de points irrationnels. Mais ces points irrationnels à ce second moment de mon histoire, vous ne pouvez les considérer que comme des lacunes, c’est des trous dans la continuité. D’où le coup de tonnerre, c’est que [Pause] le compact et le convergent [10 :00] ou la série des points, la série infinie des points rationnels, ne suffit pas à définir le continu. [Pause] Ça va ? Il n’y a plus qu’un épisode alors.

Donc comment s’en tirer ? Il faut, il faut, tout ça, ça s’étale sur beaucoup de temps de recherche, il y a eu mille manières de s’en tirer plus ou moins bien. Mais enfin, la grande manière, la grande manière de s’en tirer faudra attendre la fin du 19ème. La fin du 19ème, il y a un grand mathématicien qui s’appelle [Richard] Dedekind, d-e-d-e-k-i-n-d, qui va relancer [11 :00] le problème du continu. [Pause]

Et son idée, elle est toute simple ; il se donne le schéma suivant, à savoir que tout point — tout point, sous-entendu rationnel, ou tout nombre rationnel, peu importe — tout point ou tout nombre rationnel opère une « coupure ». C’est-à-dire le premier mérite fondamental est qu’il ne faut pas confondre toutes les notions. Tout à l’heure, je parlais de lacune, là je parle de tout à fait autre [12 :00] chose. Tout point rationnel opère une « coupure » [Pause] sur une droite, ou ce qui revient au même, tout nombre rationnel entier ou fractionnaire constitue une coupure dans la suite infini des nombres rationnels.

Deuxième point : qu’est-ce que ça veut dire une « coupure »? Couper, la définition doit être très stricte parce qu’il s’agit de mathématiques : c’est répartir un ensemble en deux classes [Pause] [13 :00] dont l’une sera, à votre choix, au-dessous et l’autre au-dessus, l’une inférieure et l’autre supérieure, l’une avant, l’autre après. La coupure de toute façon répartira notre ensemble en deux classes. Par exemple, [Deleuze se déplace vers le tableau et y dessine] si je donne un segment vertical, je dis, le point x comme coupure répartit l’ensemble AB en deux classes dont l’une est au-dessus, [14 :00] l’autre en-dessous. [Pause]

Troisième point — il faut bien suivre, ce n’est pas difficile du tout ; Dedekind, c’est très difficile, mais ce que je dis c’est très, très facile — troisième point [Pause] : tout point de la classe inférieure, dans ce cas celle d’en-dessous, tout point de la classe inférieure, supposons, est en-dessous ou inférieure à tout point de la classe supérieure. [Pause]

Quatrième [15 :00] remarque : x, la coupure, fait partie de l’une ou l’autre des deux classes, [Pause] la classe A en-dessous, la classe B au-dessus. Vous pouvez décider à votre choix que x fait partie de la classe A ou que x fait partie de la classe B. [Pause]

Un étudiant : Comment peut-on choisir en fait sur le côté… ?

Deleuze : Tu choisis tour à tour, tu fais les deux choix, tu fais les deux choix successifs.

L’étudiant: D’accord.

Deleuze : Tout ce que tu peux dire c’est que si il appartient à x, s’il appartient à la classe A, il n’appartient pas à la classe B, et inversement, [16 :00] mais tu n’as aucune raison de choisir l’un plutôt que l’autre.

Dernière remarque : toute droite comporte une infinité de coupures, ou si vous préférez, la série des nombres rationnels comporte une infinité de coupures, chaque nombre rationnel étant une coupure. [Pause] D’accord, pas de difficulté ?

Alors c’est là que la merveille va surgir. À nouveau, on va, si vous voulez, de catastrophe en merveille parce que Dedekind nous pose une question simple. Eh ben d’accord, ma droite, là, vous vous rappelez ? Elle est pleine de lacunes ; [17 :00] les lacunes, c’est les nombres irrationnels. [Pause] En d’autres termes, ma droite comporte une infinité de coupures, voyez, mais c’est une astuce diabolique : il est en train de définir le continu par la coupure.

A partir de là, jamais plus les rapports — c’est-à-dire il fait la grande réconciliation du nombre et de la grandeur, mais à quel prix ? En changeant radicalement le concept de nombre. C’est ça un grand mathématicien. Alors là, je dirais presque quelle différence il y a entre un mathématicien et un philosophe ? Je veux dire, si vous acceptez ma définition que je vous ai toujours proposée de la philosophie, à savoir que c’est une discipline qui consiste à inventer les concepts, là je prends un exemple en mathématique, de grande invention de concept, [18 :00] à savoir : l’idée de définir le nombre par la coupure. Ça, c’est signé, c’est un concept autant que le Cogito est signé Descartes, définir le nombre par la coupure, ça n’avait jamais été fait, jamais. Comment on définissait le nombre ? On définissait par : unité et addition ; il fallait se donner les notions d’unité et d’addition pour engendrer le concept de nombre.

Un étudiant : Il y a une lacune en vous ; je réfute le mot « diabolique » au profit du mot « intellect », excusez-moi…

Une étudiante : Plus fort !

Deleuze : Vous quoi ?

L’étudiant : JE RÉFUTE LE MOT « DIABOLIQUE » AU PROFIT DU MOT « INTELLECT »

Deleuze : D’accord.

L’étudiant : Voilà, merci.

Deleuze : D’accord, mais j’ai dit diabolique ?

L’étudiant : Oui, vous l’avez dit

Deleuze : Oh mon Dieu ! [Rires] C’est, c’était un lapsus. [19 :00] Vous comprenez, on ne voit pas encore ce qu’il y a d’étonnant parce que il se trouve dans ce problème, donc, il a son infinité de coupures ; toute droite comporte une infinité de coupures, mais elle comporte aussi une infinité de lacunes : les nombres irrationnels. Si tout nombre rationnel détermine dans la droite, sur la droite, si tout nombre rationnel détermine sur la droite une répartition telle qu’on vient de le voir, une répartition en deux classes, eh ben, d’accord. Mais les lacunes, les nombres irrationnels, ce n’est pas des coupures ; c’est des lacunes. Et le problème de Dedekind, ça va être : comment donner à la lacune un statut de coupure ? S’il réussit à donner à la lacune un statut de coupure, il a gagné, c’est-à-dire il a unifié tous les nombres [20 :00] sous le concept de coupure. À ce moment-là, le genre du nombre, ce sera la coupure. [Pause] Et si vous voulez, c’est à la fois, c’est arithmétiquement une espèce de révolution. [Pause]

Et comment il va faire ? Ben en effet, essayons sur son schéma-là, je reviens à ce schéma-là, de marquer une lacune. [Deleuze revient au tableau et y dessine] Il suffit que je prenne pour classe, par exemple, cas simple : je prends pour classe les deux classes, puisque une coupure opère une répartition en deux classes ; ben, là, [21 :00] je prends le cas le plus simple : le nombre 2, et j’ai mes deux classes, 2 étant considéré comme coupure. J’ai dès lors mes deux classes, tous les nombres plus petits que 2 et tous les nombres plus grands que 2. [Pause] C’est une coupure ; tout va très bien. Supposons que je définisse mes deux classes maintenant de la manière suivante : tous les nombres dont le carré est plus petit que 2 [Pause] et tous les nombres dont le carré est plus grand que 2. [Pause] [22 :00] Racine de 2 est un nombre irrationnel, c’est une lacune. En même temps, il suffit que je dise ça, vous devez déjà sentir de quelle manière il est déjà en train de ramener la lacune à un cas particulier de coupure. [Pause]

Car vous vous rappelez la condition de la coupure rationnelle, c’est-à-dire, coupure opérée, répartition opérée par un nombre entier ou fractionnaire. [Pause] C’est que tout terme, tout terme de la première classe [23 :00] doit être plus petit que tout terme de la seconde, [Pause] et le nombre qui marque la coupure doit être compris, soit dans la classe inférieure, soit dans la classe supérieure. 2 fera partie d’une des deux classes, si vous prenez 2 comme coupure. Si 2 — à votre choix, purement conventionnel — si 2 fait partie de la classe supérieure, vous direz [24 :00] que la classe supérieure a un début. En revanche, la classe inférieure n’a pas de fin ; elle n’a pas de fin puisqu’elle converge à l’infini vers 2, [Pause] dans une série convergente. Inversement si vous considérez 2 – qu’est-ce que j’avais dit ? – oui, comme début, j’avais dit : premier cas vous le considérez comme début de la classe supérieure. Second cas, si vous le considérez comme fin de la classe inférieure, la classe inférieure a bien une fin, la classe supérieure n’a pas de début. Bien. [Pause] [25 :00]