June 18, 1985

Until now, since I have been at Paris 8, and it is very normal, I’ve changed the subject every year. And this really isn’t such a big deal since … I’ve always been teaching on the research I was developing. So, for me, the courses and the research were reconciled, reconciled wonderfully. … I had announced that we would go much further in Blanchot, in Blanchot and in Foucault. No, in fact, because next year, … could we not develop something like that? Or it would be for a year, but not a sequential course. … But I find that … there is something hard. I mean, there is something great in what we do there, in the aggregate that we form, but there is also something too hard … On the other hand, not giving classes, I don’t understand it; I mean doing sessions like today. … So maybe it would be a solution to proceed by request, maybe it would break [things] up… I would like those who intend to return next year to think a little about a solution, which would be more, in any case, for a year, which would be more than the courses as I’ve done until now.

Seminar Introduction

As he starts the fourth year of his reflections on relations between cinema and philosophy, Deleuze explains that the method of thought has two aspects, temporal and spatial, presupposing an implicit image of thought, one that is variable, with history. He proposes the chronotope, as space-time, as the implicit image of thought, one riddled with philosophical cries, and that the problematic of this fourth seminar on cinema will be precisely the theme of “what is philosophy?’, undertaken from the perspective of this encounter between the image of thought and the cinematographic image.

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

In another q&a session, the first question, on the concept of the “utterable” (l’énonçable) (see session 17) in relation to another concept, the act of fabulation. Deleuze’s 90-minute response returns him to discussing questions of linguistics (notably, Hjelmslev and Gustave Guillaume), then to consider, with Bergson, how the sign operates a “cut” or “point of view” within sense as a kind of pre-linguistic material. Cinema, Deleuze argues, is the representation of the utterable, either as movement-image or time-image, but particularly as process of temporalization, and experimental cinema, Deleuze says the enunciable is developed any-spaces-whatever, i.e., the pure potentiality of the event. This perspective shifts Deleuze’s focus to develop questions of the proposition and the event (cf. Logic of Sense), juxtaposing the Stoics’ concept of the “expressible”. Deleuze links the proposition and sense to cinema since, for him only through the cinema image – movement-image, time-image –, does the signified of power, or sense, or matter directly emerge as structure of movement or process of temporalization, via a shift from interior monologue to indirect free discourse. The session’s final part focuses loosely on possible topics for the 1985-86 seminar: first, “what is philosophy?”, but then, after hearing different suggestions, Deleuze mentions Blanchot and Foucault, even a return to Syberberg in relation to concepts from Blanchot. This process of speculation leads Deleuze to return finally to reflections on forms of political cinema (developed in The Time-Image, chapter 8), specifically on “acts of fabulation” in cinema and in art related to the notion of “the people are missing” and the concomitant need to fabulate as a process of self-invention as a “movement”.

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Cinema and Thought, 1984-1985

Lecture 26, 18 June 1985 (Cinema Course 92)

Transcription: La voix de Deleuze, M. Fossiez (Part 1), Laurène Praget (Part 2) and Stéphanie Mpoyo Llunga (Part 3); additional revisions to the transcription and time stamp, Charles J. Stivale

Translation, Charles J. Stivale

Part 1

Deleuze: Yeah, that’s ideal, it would be like that all year round, [and] that would entirely change the nature of the work! But anyway, since that’s not how it is! [Pause] Next year, that’s how I’ll do it. Well, I’d like… I’m saying next year because I have problems about what to do — but since you might not be here next year, I’ll have to wait until next year to explain my problems! Well, does anyone want to ask questions? Because right now, the conditions we have are good,[1] so, any questions, yes, about… yes! Anyway! Anyway, what?

A student [Christian]: This is about the “enunciable.”[2]

Deleuze: Ah, yes.

Christian: You’ve identified the enunciable to some extent with interior monologue…

Deleuze: In one case.

Christian: In one case, in relation to the sole process of insertion or specification. Well, I’m asking you if the passage from [Inaudible remarks] to an act of fabulation entails a change in the enunciable and the relationships between the enunciable and the process of the order of time and the process of deviation and ordination. Can we say in this case that we might identify the enunciable in modern cinema with free indirect discourse?

Deleuze: Yeah, yeah, yeah, I understand the question very well. Did everyone hear that? [Pause] The question is very good because this concerns a part that is quite vague. I am very aware that in what I said about the enunciable and how to use this notion in relation to cinema, I stated that still quite vaguely and a little rapidly. As we are in special conditions here, in which we can… For me… In fact, everyone must have understood that it is a way of escaping linguistics.

So, what is vague about this notion? And I could try to make it less vague. What I was getting at was that it was a notion with a place among certain linguists, but that it was a very, very strange notion. If you like, let’s say that linguists consider linguistic units and linguistic operations, linguistic units of different levels, for example, the phoneme, the moneme, etc., and they also consider linguistic operations, as we have seen: syntagma, [Pause; Deleuze is looking for the term] paradigm. [Pause] When they say that there can be [spoken/written] language without langue [language system] — we have seen this, I have developed it a lot — they mean this: we can conceive of syntagmatic and paradigmatic operations independently of linguistic units. Alongside linguistic units, there are necessarily operations, and you have a language with a langue; if you have linguistic operations independently of linguistic units, you have a language without a langue. Hence the whole school in cinema inspired by linguistics will say: “cinema is not a langue, but it is a language,” since there is no point in looking for linguistic units; on the other hand, there definitely is a point in looking for linguistic operations of the syntagm and paradigm type, right? Here we have a clear position, the position of all linguistically inspired semiology. [Pause]

So, this [approach] doesn’t work for me. Why doesn’t it work for me? We’re at the level where it’s not about saying they’re wrong. Let’s assume the work they do is excellent. Why doesn’t it work for me? Because, for reasons I won’t go into, this semiology radically eliminates the notion of thr sign. In fact, they no longer need the notion of the sign. They replace the sign with the signifier or signifiance [interpretation]. We must not believe that the signifier or social signifiance implies the notion of the sign; these destroy the notion of the sign. So already, they cause the notion of the sign to go up in flames.

Myself, for a thousand reasons… This is the sense in which I tell you: theories are never true or false. Something within us causes them either to suit us or not, but that doesn’t mean that this occurs based on our whims. Indeed, many reasons stronger than reason exist that cause us to be more or less attracted by a theory. [The linguists’ interpretation] doesn’t work for me at all since I place great importance on the notion of the sign, and you understand, a semiology that eliminates the sign disturbs me enormously. Moreover, the notion of the signifier seems to me… it revolts me. So, that’s quite a list of things, the reasons why, personally, I cannot feel any attraction to… If one of you were to tell me, “this is the direction that suits me,” I could only respect that, and I’d say: follow your path, but not at all meaning, shove off then. Rather, [I’d mean]: follow your path in that direction.

So. on the other hand, [that theory] also eliminates the notion of image. The operations of the signifier will replace it. So, of course, they’ll talk, they’ll talk about the “imaginary,” they’ll talk about the imaginary in its relationship with the signifier, etc. But the notion of image flames outs along with the notion of the sign. It is replaced by the themes of the language of the syntagm, of the paradigm, and of the signifier or of signifiance. So, all of that doesn’t suit me because… it doesn’t suit me. So, once it’s said that [their theory] doesn’t suit me, that’s of no interest except for me. It only risks gaining interest when I tell myself: once you admit that it doesn’t suit you, what are you going to do? To say that at this level, thought is like action, what will the outcome be?

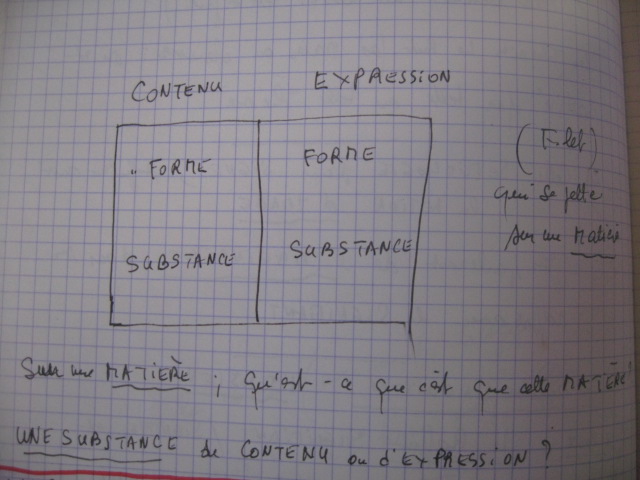

So, let’s assume, I’m looking for — this already implies a lot of work — in a last desperate effort, I was looking around for some linguists. And here I find one who causes me problems. He quite possibly won’t be a problem for others. He is a problem for me because I find him admirable, particularly admirable among all linguists — and I’m not the only one — and there’s a small detail in his works that particularly interests me. This is [Louis] Hjelmslev. In Hjelmslev, first of all, an initial point exists in which the “signifier-signified” relationship is replaced by an “expression-content” correlation, an “expression-content” complementarity. [Pause] Expression presents a form and substance; content presents a form and substance. See [how] the relationship, the signifier-signified couple gets developed in Hjelmslev: into expression, form and substance of expression; content, form and substance of content.

You will ask: what does all that mean? So, we’ll just move on. Because what interests me is the relatively rare term, developed by Hjelmslev — I’m not the one who discovered it; all linguists have delimited [these terms] — employing an English term that is sometimes translated as “matter” and sometimes as “sense” — “matter” [matière] seems to me quite good as a translation — he tells us exactly or more or less this: [Pause] expression and content cast their net — he doesn’t use [metaphors] often, Hjelmslev doesn’t speak in metaphors; linguists rarely speak in metaphors, they are men of science — and here we find in Hjelmslev, this very beautiful metaphor: forms and contents which are correlative notions internal to language, cast their net — so the net is a form of substance — over a matter. [Pause][3]

I’m saying that whatever might be… [Deleuze goes to write on the board; he looks for chalk]

Lucien Gouty: Here, I’ve got some, I’ve got some. [He provides him with chalk]

Deleuze: Ah, all the way to the very last [session]! [Pause] So if I have my linguistic system, [Pause] expression-content, and for each of these, form and substance, it is a kind of net that is thrown over a matter. [Pause] What does this matter consist of? And indeed, what will he call “a substance of content of expression”? Substance is always a formed matter. So, there is a matter — how to express this? — which is not without form since the linguistic net is thrown over a matter. When the net is thrown over a matter, this matter becomes substance, and matter which therefore precedes, at least from a logical point of view, [which] precedes both the content and the expression, and the form and the substance – let’s call it… — and which nevertheless is strictly correlative to language, [and] correlative to language, this is not physical matter. [Pause]

And the expression that Hjelmslev uses is both matter and sense… [These comments are barely audible; Deleuze is at the board while speaking very softly to students nearby, hence the approximate nature of this two-minute segment] So, right here, [Inaudible word] I must find the term; [Pause] this is a problem in whoever translated Hjelmslev: [Pause] [Inaudible comment; Deleuze seems to be searching in a text while he talks somewhat to himself; he reads the term in English] A “matter”… it’s “matter,” I think… [A student makes an inaudible suggestion to which Deleuze replies] No, because that way, there’d be no problem… I have an idea; I can simply refer you to the translation where the translator has [Inaudible words]; it’s in the Prolegomena [to a Theory of Language];[4] I know that there’s an ambiguity with “matter,” but I don’t dare say that [Inaudible words] because that would be too [Inaudible word]… but it really is “matter,” with the general idea in English of the dual sense of matière [material] and of “what’s at stake” [matter] [ce dont il s’agit dans]… Fine.

Lucien Gouty: Isn’t it what’s called “hylé”?

Deleuze: It’s a “hylé”… yes, it’s as complicated as what Husserl calls “the hylé” or there are all sorts of them; ah right, yes, in my opinion, that would come close to what Husserl explains as the “hylé” passing through meaning, but importing Husserl is not likely to make these things any clearer for us. So fine, I’ll hold onto that, [but] I’ll put that aside, this kind of matter equals x… [Interruption of the recording] [16:39]

…and I come across a linguist contemporary to [Ferdinand de] Saussure, Gustave Guillaume, [Pause] Gustave Guillaume. The first person who spoke about that in France, as far as I know, was [Maurice] Merleau-Ponty at the end of his life; and as at the end of his life, he knew [Jacques] Lacan well, he was very close to Lacan. I think there was a rivalry, each [with] his own linguist, not a very friendly rivalry. Whereas Lacan was to discover Jakobson, for Merleau-Ponty, he discovered Guillaume. And when you think about it, Guillaume appears extraordinarily serious and constitutes the work among linguists of a kind of autodidact who creates a linguistics that resembles no one’s, and even now it resembles no one’s. And as I told you, for those who want Guillaume’s publications, they are both difficult to find and very scattered; I referred you to a book that provides some explanations, but which precisely says nothing about what seems to me the most interesting but says a lot about Guillaume’s linguistics. The book I mentioned is by [Edmond] Ortigues, Le discours et le symbole chez Aubier [1962]. There is a whole section on Guillaume’s linguistics.[5]

What I take away from Guillaume is this. Guillaume tells us — and once again, it’s very curious that Ortigues doesn’t take any notice of this — Guillaume tells us the following tale — so I would like you to feel how, independently of any influence, a common theme exists with what we have just seen for Hjelmslev — he tells us: linguistics is made of signs. And what is the sign? Well [Pause; Deleuze writes on the board] the sign is the condition, the correlation [of] the one signifying and the one signified. Up to that point, this could be Saussure. [Pause] Where it ceases to be Saussurean is that he is going to tell us: so here, this is how, this is how he conceives the signifier-signified relationship: the signifier is going to have a primacy — and this is also very Saussurean — there is going to be a primacy of the signifier in the sense that the signified is an effect, it is an effect of the signifier. [Pause] So, a signified will be a signified that [Guillaume] himself will call a “signified of effect.” [Pause]

Where does this signified of effect come from? How does the signifier constitute a signified? Here’s his answer: we must understand that there is a first signified – this is where I’ve lost the word again… ah yes! – there is a “signified of power” [signifié de puissance] that must not be confused with the signified of effect. The signified of power is at the same time correlative to language – “power,” eh? He uses “power” [puissance]; we will find exactly the same problem – this signified of power is strictly correlative to language, but it is external to the signifier and to the signified of effect. It is even primary; it is what makes language possible. Why? Because the signifier is going to be a point of view. The sign or the signifier is a point of view on the signified of power.

It’s a bit Bergsonian, and Guillaume knew Bergson. You see, [it’s] a bit like there are points of view on a movement or cuts on a movement. The signifier makes a cut or imposes a point of view, on a signified of power, and that’s how it produces a signified of effect. The signified of effect is what the signifier produces when the signifier makes a “cut” on the signified of power. Which amounts to saying what? He can’t not be Bergsonian! The signified of power [Pause; Deleuze writes on the board] is necessarily a movement or a duration. The signifier realizes a cut on a movement or a duration. By realizing a cut or taking a point of view, it produces a signified of effect. [Pause]

What does this signified of power mean? I insist on the word “power” [puissance]: it is a potentiality. Indeed, it has no actuality in language. Language will only present us with signifiers or the signified. So, a signified of power indeed pre-exists language while, at the same time, being like a correlative, is inseparable from language. Why am I insisting on the word “power” [puissance]? Because, see how this resonates with “matter” proposed by Hjelmslev – let me warn you, I am forcing things; I am making a connection, so they must be forced — I remain very cautious, however, in saying: in my opinion, there is something in common between Hjelmslev’s “matter” and Guillaume’s “signified of power” — for example, if you think — even if only at the terminological level — of the constant relationships between “matter” and “power” as they exist in the concept, in philosophy, since Aristotle. And so, it seems to me that the advantage… he would tell us, Guillaume might very well tell us, [that] the couple, the signifier which produces a signified, the signifier which is a point of view of the couple, casts its net over the signified of power. So, the signified of power is literally a matter-movement or a duration, or a movement, which is of this nature, or a temporal process.

This is unclear! I’ll try to explain it to you more concretely. I’ll just remind you, well yes, we have, for example, a movement. He gives us two examples at the level of movement: particularization-generalization. [Deleuze writes on the board] These examples enlighten us. So, we’re talking about “movements of thought.” And indeed, here Guillaume comes up with a very strange term, because he is going to call the domain of the signified of power a true “psycho-mechanics.” [Pause] All linguists very harshly criticize Guillaume for a whole part of his work being steeped in the “idealist” tradition of philosophy, and not in scientific linguistics. You see that this occurs due to the very strange status of the signified of power that is not language and which, at the same time, is both presupposed by language and an indispensable correlate of language. I have movements of thought: movements of particularization, movements of generalization. The signifying sign produces cuts or points of view within this movement; the same goes for particularization, that is, a particular degree of generalities, a particular degree of particularities or particularization. And [this sign] produces a signified of effect to the extent that the sign as signifier produces these cuts. [Pause]

So, this was evident regarding the article. According to Guillaume, all the different meanings of the indefinite article “a” or the definite article “the” are points of view on the movements of particularization and the movements of generalization, which, themselves, are signifieds of power. So, I ask, what also interests me in this? I’m making a connection: there is the signified of power, yes, and it is also a spirit-time [un esprit-temps]. [Pause] And I can also say that it is a matter and that it is a sense, that it is sense [le sens]. That’s what sense is! Why?

I think back to Bergson’s rare texts on language, when Bergson says: “But you don’t start with signs at all; what happens when you speak?” And there, he’s not dealing with linguistics. What happens when you speak? When you speak or when you listen to someone else, when you speak with somebody, you have to insert yourself — no doubt that’s why [indistinct word] you have to have a void, we’ll see what void — but you jump into a domain which is sense. In fact, you need reference points. These are signs, sounds, whatever you want. You still have to perceive them. What is it that prevents me from speaking with someone whose language I don’t know? It’s that I have absolutely no reference point that places me within this common domain which is sense. When I tell you, there is never any point in arguing — here too I feel very Bergsonian in this regard — what does that mean? It means that in order to argue, you have to establish yourself in a common domain with the person you are speaking with; you have to establish yourself in this domain. This common domain is what we call “sense.” [Pause] Sense is neither true nor false! But if you don’t establish the minimum of “common sense” with the person you are speaking with, [Pause] there is no room for discussion, no place for arguing. You could argue only for the fun of talking for its own sake.

That’s what I’m calling both “the problem” [of] sense, [and] “the problem” [of] matter; they’re the same thing. If you have no common problem, what is there to discuss? That’s truly talking for its own sake. You’ll continue, everyone will pursue his or her monologue. And if you share the common problem, the common sense, there’s no room for arguing in this case either. Why? Not at all because you agree with each other, but because you are involved in a relation with the other, a working relationship. This isn’t discussion; in this case, it’s collaboration. Collaborating does not at all mean arguing. So, in any event, there’s no point in arguing since there’s never a reason for doing so. [Pause] That’s what is so painful with things on TV [where] the people there will always have the same problems [and] can keep on talking… [Several unclear words]

What can we say, exactly? In our own way, we’re making a little progress. I recall from Hjelmslev this very strange notion of extra-linguistic “matter” that is specific to language, specific to language, a matter that would not be linguistic, but that would be specific to language. [Pause] In Guillaume’s works, I recall the signified of power that appears in the same case: a matter specific to language and yet which is not in itself linguistic. What I’m saying is: this is what sense is. For me, a proposition’s sense, a statement’s sense, is precisely this matter on which, or this movement, or this process on which the sign produces a cut or establishes a point of view. As a result, Bergson tells us clearly: when you speak, you go from sense to sign and not from sign to sense. You must first establish yourself within sense to form your sentences. You form your sentences by tearing them away from this matter; let’s call that “pre-linguistic matter”; although it is specific to language, it is not a matter. You can only grasp it through the cuts of language. [Pause]

You see what advantage Guillaume derives from this. You might ask me: how does this help him? It helps him do something fundamental because, for many authors and scientific representatives in linguistics, [this field] was moving towards a conception based on oppositions, for example, phonematic oppositions, oppositions of phonemes. I understand that major differences have existed. The major differences concerned the way opposition was conceived. For example, it is obvious that a linguist like [André] Martinet does not conceive opposition in the same way as a linguist like [Roman] Jakobson. But for them, and as opposition was derived from phonologists, from [Nikolai] Trubetskoï, from the great phenomenology, opposition was categorically the advantage of language, as was already the case for Saussure. And that is what [Saussure] meant with the idea of difference; linguistic difference in Saussure, it was opposition [or] langue as a system of difference.

In Guillaume’s work, what’s important is that for him, oppositions do not constitute the linguistic relations; [these stem from] the relative positions of the sign. The sign or signs traverse relative positions. You see why this is the direct outcome. Given that a sign is a point of view on a signified of power, that is, on a movement or on a process, indeed, a set [or] a category of signs will be defined by the relative positions of each sign. A category of signs will be defined by this: they have the same signified of power, but they represent different relative positions, that is, they produce different cuts or different points of view on this signified of power. So, this will constitute an entire linguistics of “differential” positions, [Pause] very different from the linguistics of “oppositions.” [Several indistinct words] But once again, in my opinion, if you eliminate the term “signified of power” as being primary, you cannot maintain this linguistics of positions by difference with a linguistics of oppositions because, at that point, the language system closes in on itself. If you do not take that into account, or [take] only that, the language system closes in on itself and can no longer be governed by anything other than what? Form-substance opposition, content-expression opposition, etc.

So, what is it that I’m calling the enunciable? It’s Hjelmslev’s “matter,” the “signified of power” [puissance]. For my part, I’m indeed saying that this is sense. [Deleuze returns to his seat] Sense is this pre-linguistic correlate, proper to linguistics, proper to language, specific to language; it is the matter of language. Or, I could say just as well [that] I understand the accusation of idealism, but I don’t care. I could say just as well that it is the spirit, it is the spirit of language; it is a matter-movement or it is a spirit-duration, a spirit-temporality. [Pause]

So, what use is this to me, however vague it may be? We would have to clarify the status of this enunciable aspect. So, what Hjelmslev calls “matter” and what Guillaume calls “signified of power,” I call enunciable. Why? Because we understand that the enunciable, in part, captures the idea of potentiality; we see clearly that the very word “enunciable” is something that is not part of the statement [l’énoncé], and it is something without which the statement would not exist. I would say that every statement is a point of view on the enunciable, on an enunciable aspect. If someone says to me: “but where does the enunciable exist?”, I can say: it does not exist independently of language, but it itself is not, does not belong to language. Fine. It’s the correlate of language. [Pause]

As a result, it was very useful to me regarding our problems in cinema. In what sense? I was saying: cinema is neither langue [langue system], nor language. Why? Because it is a set of images and signs that constitutes the enunciable. [Pause] Cinema is the representation of the enunciable. So, it is neither a language, nor a langue. [Pause] Well, what does representation of the enunciable mean? It means: sometimes it is the movement-image, sometimes it is the time-image, with the corresponding signs. [Pause] So there will be signs of the movement-image, [and] there will not only be signs, there will be types of movement-images. Just as Guillaume distinguished between particularization and generalization, I was no longer interested in this because it didn’t work within the context of cinema. I was trying to discern the major types of movement-image that constituted an enunciable aspect: the cinematographic enunciable. [Pause]

And then as we continued to discover the existence of a time-image very different from the movement-image, there I sought to define temporal processes that cinema presented to us, that it presented to us directly without going through movement, or independently of movement. So, I would say that that was the time-image as enunciable, that two enunciable aspects exist, two great enunciables, each with their signs, I mean rather, each possessing their type: type of movement, type of temporalization, and each with their signs. I said that is what cinema is. So indeed, to answer Christian after this long detour, I believe, in fact, that the enunciable is not the same in the framework of the movement-image and in the framework of the time-image. It is not at all the same.

Christian: [Inaudible comments at the start] … because in saying that, cinema and the novel can even be radically distinguished, for example?

Deleuze: Completely, radically… yes and no.

Christian: Because if two types of the enunciable exist, that’s even better, I think, at least for me. That gives me other possibilities for moving beyond the problem of narration.

Deleuze: I do think that temporal processes constitute an enunciable aspect. If I refer again to linguistics, I would say, well, movements — it seems strange but only at first glance — movements are above all given by the substantive or noun. The movement-image is substantive, in certain language systems like ours, with the noun being the article-noun combination, while the time-image is something else, as given by the verb: the processes of temporalization. That is, it is the correlate of the verb, the processes of temporalization, the “chronogeneses,” you know. While the movement-image gives us — and here, we could create words, but that has no use — it gives us “kinostructures.” We should distinguish, in the same way that we distinguished the movement-image and the time-image, we can distinguish “kinostructures” and “chronogeneses.”[6]

So, in fact, that would form the enunciable which is the matter specific to cinema, the object specific to cinema. So, that doesn’t prevent cinema from possessing a language. Yes, [cinema] is not a language, but it does possess a language, and we have seen, in fact, that there were cinematographic statements, that these statements could be silent, that is, [statements that were] read, and that they could be speaking, and that they could be speaking in several ways. But I believe that what will be specific to cinema is that [for] cinema, when it produces statements, these statements are cinematographic only to the extent that cinema uses them to re-enlarge the enunciable, that is, it does the opposite.

If the movement of language is to grasp the enunciable within the net of statements, the whole movement of cinema means to project the statements that it produces through the form of the silent or the speaking, to project the statements that it produces or that it uses, to re-enlarge them, to give them back to the enunciable, that is, literally to “recharge”, yes, to recharge the enunciable, that is, the set of images and signs. That would be good, working like a counter-entropy. It would recharge the set of images and signs… Yes?

Christian: Can we assume [there are], for example, back-and-forth movements in relation to the enunciable and statements? For example, in experimental cinema, we find a tendency toward asking questions about the enunciable but [questions] that are actualized by a statement.

Deleuze: Absolutely; and one could even say, at that point, one would have to say that they have positions very close to the enunciable. Everything that we’ve discussed in previous years, about any-spaces-whatever [espaces quelconques], for example, were typically spaces of potentiality. A whole aspect of experimental cinema, in fact, considers space as pure potentiality of event, the event not being given. Pure potentiality of events, yes, empty spaces by definition or disconnected spaces are very close to a pure enunciable. That is, this is indeed the operation by which cinematographic statements render the enunciable.

So, if you will, from the point of view of logic – so, at the level of cinema, I find something that interests me greatly in philosophy; what interested me in philosophy? But these are old topics, things I was working on a long time ago, like many other people[7] — I asked myself: what is the sense of a proposition? What is the sense of a proposition? And what interested me in answering this question, and you will see how everything comes together, if you grant me a few more minutes of philosophy and logic, what interested me was a whole tradition that begins with the Stoics and continues throughout the Middle Ages, and that tells us: the sense of a proposition, the sense of a statement, is what they call, it’s what the Stoics already call “the expressible.” It comes back exactly to “the expressible.”[8]

So, what is the expressible? On that point, they tell us very strange things. [Deleuze returns to the board] They tell us: It’s an entity, it’s an entity that has no existence. Ah, really, an entity that has no existence! That’s their idea: existence doesn’t exhaust the set of entities. Non-existent entities exist. Does that mean they’re in our heads? Not at all, not at all, a non-existent thing [du non-existant] exists. There’s no reason to identify being with what exists [l’existant]. Fine. What are they going to do? They’re going to create some very beautiful theories in the Middle Ages, [when] there’s an abundance of these theories, but they are as beautiful as our [indistinct word]. They’re going to distinguish, within the statement, they’re going to distinguish the components of the statement. For example, for the Stoics, the components within the statement are physical; they are phonetic.

So, that’s not what sense is. They’re going to distinguish the state of things to which the statement relates. When I say, “snow is white,” there’s an object: snow, the sky. Or [when] I say: “God is.” So, their trick — but it’s not for fun — was to deem it necessary to discover a third instance. You see why there’s a need for a third instance? Because otherwise, there would be no assignable relationship between the statement and its object. The object has a physical or mental existence, that is, the imaginary is on the side of the object. The object has a truly physical or psychological existence; the statement, that’s what you say, it’s linguistic. Why would you look for the slightest relationship? And how can any relationship whatsoever be established between linguistics and objects? How can any relationship be established between words and things? In this, you see their problem. And what about their answers? Well, [indistinct word] there too, notice the extent to which it’s not worth discussing. You can very well say: the problem is badly posed! You can very well say: that’s not how the problem must be posed.

If you agree to pose the problem in that way, well, “statements” are systems of words. They have a referent: the object. We will call this reference “the designated” or the referent. Whatever, there are a thousand words. And what is the relationship you’re looking for? What makes the designation possible, that is, the fact that a statement is in relation to an object or a state of affairs? If you accept the problem posed like that, henceforth these authors are the ones who matter to you, [and] you are ready to listen to them. If they don’t matter to you, you say: that’s not for me. And here’s what they tell us; they tell us, well, there is a third instance. You sense that the third instance will be important to bring [Pause] [indistinct words]. [Pause][9]

They will call this third instance “the expressible,” that is, sense. [Pause] Why not signification? It’s because signification doesn’t work either — I didn’t want to get into this, I’ll say it very quickly – signification is easy to define at the level of the concepts that correspond to the words. The expressible or sense is something from logical concepts. So, what is this expressible or this sense? Well, they are very embarrassed because they will try to make us feel — it’s such a new notion, each time there is a new notion, they need to have a… — they will tell us: well, what is this expressible of the proposition “God is”? It’s “God [dash] to be” [Dieu-être] or “God-be-ing” [Dieu-étant]. They sometimes use the infinitive, sometimes the participle. In my opinion, a question mark must be added because they will say that the statement “God is” and the statement “God is not” have strictly the same “expressible,” namely, God being [Dieu-étant] or the be-ing of God [étant de Dieu]. [Pause]

The expressible of “snow is white” is: “snow to be white” [neige être blanc] [Pause; a few indistinct words] For the moment, you only see a trick of terminology. They feel the need to give the expressible a formulation different from that of the statement. Hence their use of the infinitive or participle form. What do they mean, then? They mean: you see, the expressible is a very strange entity; it is not an object, it is not a concept. The word “entity” really is appropriate. It is a very strange entity because it is at the same time the expressible of the proposition, and in this sense, it refers to the proposition, and on the other hand, it is the “logical” attribute of the thing or of the state of things. [Pause; Deleuze returns to his seat] That is, a thing does not only have physical qualities, it has logical attributes. As a result, the expressible has a reverse side and a front side. On the one hand, it is a logical attribute of the state of things that must not be confused with its physical qualities; on the other hand, it is the expressible of the proposition that must not be confused with the elements of the proposition nor with the concepts that the proposition brings into play… [Interruption of the recording] [59:48]

Part 2

… Yes, all that is not clear, no, it’s not clear. We find this third instance very, very curious. But you see that, if this third instance exists, if we manage to give it consistency, they’ll say as the ones introducing the great topic: while it does not exist, it “insists”. They will distinguish “existere” — they write in Latin — and “insistere” or “instare.”[10] Entities are insistences; they are not existences. It “insists,” it does not exist. What do they mean? This is the expressible of the proposition: it’s the logical attribute of the state of things. It’s through them that propositions can designate things.

Well, fine, but other than these stupid formulations, what are these then, “God-to be” which would be the expressible of the two statements, “God is” [and] “God is not”? I’m saying: we have no choice. After all, perhaps it’s one thing, well [one thing] also among others, it’s the problem that is never explicitly stated, to which one [statement] responds like the other, or in relation to which the two statements — “God is” and “God is not” — are the four solutions. Fine, [Pause] this is a way of, this is a better way to express it. Because, you understand, I mean the problem at that moment is not the same thing as a question. You can always ask someone, as someone asked Sartre while he was getting off a plane: Does God exist? [Laughter] Well, fine then [Laughter], we answer… understand, what is… If someone asks me: “what time is it?”, that’s a question. In this case, you notice that the question is strictly split from the proposition. It’s two o’clock or it’s x o’clock, and you can abstract from that the question “what time is it?” which is valid for any time. The same question is… [Recording interrupted] [1:02:44]

… If you are in the least bit reasonable, what do you immediately answer? Or else, you just say, “I don’t know”; that’s the best way to end it. In any case, I’ll return to my topic [since] discussion is useless. To know whether God exists or doesn’t, there’s no point in arguing. If we ask, “Does God exist?” or “Do you believe in God?,” the only possible answer is, “Tell me in what sense you’re using the word ‘God,’ and I’ll answer you right away.” Because if someone says to me, “I’m using it in the sense of ‘being an all-powerful old bearded man’,” I answer “God does not exist.” Fine. If someone says to me, “I’m using it in the sense of [Laughter] nature, Deus Sive Natura,” and if my name is Spinoza, I say, “yes, God exists.” Fine, in any case, when he/she asks you, “does God exist?”, the smallest thing that we might reply with the minimum of politeness would be: in what sense is he/she using ‘God’? Now what is the sense in which he/she’s using ‘God’? This is the problem that he/she poses, but without stating it, the problem posed when he/she says, when he/she asks the question: “Does God exist?”. When I ask the question, “Does God exist?”, I have not at all stated the problem to which I was referring. It is absolutely unexpressed. The problems are never stated. Why? In my opinion, because they are not sayable [dicible]. They are never propositions.

And that, I think … — so there, I’m skipping everything, I’m jumping from philosophy to science — that’s why science is very exciting because even science can’t state its problems. I would say that mathematics, in a certain way, is the art of solving problems that will never be stated or at least that will only be stated each time with new symbolic creations. Create your symbols. If you even want to provide the idea of the problem you’re posing, you have to create your symbols.

So, you see, all I want, all this is a way of saying: well yes, this notion of sense or matter, the enunciable, the expressible, in fact, [while] this does not get reduced to a state of things, nor to propositions, nonetheless this explains that propositions relate to states of things. Once again, someone asks you, “what time is it?” With this, no discussion is possible so you can answer calmly. First of all, doing so is polite; it’s part of social life: you answer if you know, and it does not commit you to anything. But a problem nonetheless exists, a problem at the same level. First of all, the person who asks you, “what time is it?”, obviously has a problem, a problem that he/she is not telling you. He/She could tell you, but that does not interest you. That means, he/she has a reason for asking “what time is it?”, and this reason is extraordinarily variable. That has an impact on the answer. That is, “it’s 5 o’clock” might be a death sentence. Fine, we understand that 5 o’clock might be a death sentence. It can be the turning point of a love affair, a missed encounter, etc. Fine, all of these things are problems, right?

So, what I’m doing is stating the sense. For me anyway, that’s what sense is. As a result, this is how I would say “no way” concerning all cinema,and ultimately, that’s all I’ve tried to say. Of course, the cinematographic image presents us with states of affairs. But that’s not what makes it a cinematographic image; everything presents us with states of affairs, every image, painting, photography, etc. That’s not at all what counts. And [here’s] what counts: if I can assimilate to statements everything that presents me with states of affairs, that is, every image, let’s say, [Pause] that still doesn’t tell me what the image refers to that is deeper than the state of affairs, or, if you like, what there is in the image that is not representative of a state of things. What is there in the image that is not representative of a state of affairs? It’s the image that expresses. It’s the image qua expression, that is, insofar as it expresses something expressible and no longer insofar as it designates a state of affairs. Well then, the expressible in cinema is the movement-image; it’s the time-image.

So that’s why, in fact, I felt so different, so far removed from any linguistic criticism since, for me, all cinema settles into the level of this instance that, literally, does not exist, the movement-image, the time-image. I mean: these are “insistences,” [but] they are not existences, fine. So, in fact, it’s, it’s fully… I’d like you to feel that we have just added, we have just created a very, very fluid aggregate between Hjelmslev’s “matter,” Guillaume’s “signified of power,” and the “expressible” of the Stoics and the Middle Ages. In addition, we have added the notion of “problem” since they do not speak of the problem directly. All that’s fine, but by movement-image [or] time-image, you understand precisely this “signified of power,” or this “sense,” or this “matter” that is in my opinion, as a process [procès] of temporalization, a procedure [processus] of temporalization, or as a structure of movement, only provided by cinema. [Pause] It is only provided directly by cinema. There you have it.

So, in light of this, in fact: in what type of statement? By what type of statement will it be expressed? I’d say, that depends. In fact, for me, it seemed that [in finding] its statement, as enunciable or expressible, the movement-image referred to a kind of interior monologue extended to the limits of the world, and that is why so-called “classical” cinema found itself in the type of interior monologue, within the model of interior monologue, not interior monologue in the mind of a character, but interior monologue of the spectator, and in this regard, we had considered all of [Sergei] Eisenstein’s work. I would say that regarding the time-image, for me, the interior monologue does not account for the time-image. It does account for the movement of thought; it does not account for the processes of temporalization.

That’s why, last year in fact, I had attached particular importance to free indirect discourse as distinct from interior monologue because free indirect discourse seemed to me much more [Pause] adequate than interior monologue for grasping the processes of temporalization. And I had other reasons, namely the effective presence of free indirect discourse in very, very diverse forms throughout all modern cinema, where there was a complete break in interior monologue in favor of free indirect discourse that possesses figures, but extremely different figures.

I’ll remind you of a figure that we tried to grasp, for example, in experimental cinema, a certain type of experimental cinema in the works of [Jean] Rouch and [Pierre] Perrault.[11] It seems striking to me, namely, when Perrault says “I, as a film author, need a mediator or intercessor [intercesseur],” that is, I need for it not to be me inventing the fiction and that it be my character. And only a real character can invent a fiction. I mean a fictional character presupposes the fiction invented by the author. So, imbeciles say, therefore, Perrault is not the, he is not really the author of his films. This is a very bad understanding, a very bad understanding of his need for an intercessor. Why? Precisely because he needs the fiction to be born within the film. Fine, the Tremblay family, Perrault’s famous family, well, he uses others, the Tremblay family of Quebec plays the role of intercessor in Perrault’s film. And why do we need an intercessor? And why does the Tremblay family need Perrault as much as Perrault needs an intercessor? That’s one of the reasons why there is free indirect discourse. They are a people of minorities, a people of minorities.

What does that mean? Well, it means, it’s the same thing. We can say: it’s a colonized or formerly colonized people. This is common to all Third World cinema, right. The Quebecers consider themselves part of the Third World. So why do they need this expression? Well, yes, any pre-established fiction is a myth of the colonizer. Take note and think of [Glauber] Rocha, in South America, a very great author like Rocha, [who] starts from the same conclusion: any pre-established myth is a myth of the colonizer, including the myth of the great bandit, including the myth of the prophet.[12] The people must construct their own myths. If we mention to them, “and the myth of the bandit?,” it’s the people who construct it that reply, no, they constructed it. But it’s a myth that already no longer has any meaning in the age of cinema and in the modern age. It is a vacated myth that has therefore passed over to the side of the colonizer. It is an exhausted myth. The people must rediscover or reinvent their own myths.

But what does reinventing one’s own myths mean? It means that there must be real characters in the film who begin to fabulate. That’s what I called “the act of fabulation.” The fiction must come from them. At that point, no doubt, this fiction will also be a memory, a memory of a past where these people were in other conditions. Were they really in other conditions? Memory and fabulation, all the transitions you want. Fine, and you have an author-real character couple who fabulates. You don’t have and you shouldn’t have any prior fabulation. If Perrault is a great film author, it’s because he uses the Tremblay family as an intercessor.

With this, here’s what I’m saying: the Tremblays are no less indispensable to Perrault than Perrault is indispensable to the Tremblays. Why? Because together, they are necessary for constituting a free indirect discourse. — Do you remember what a free indirect discourse is? I’ll tell you again: it’s an enunciation taken within a statement that depends on another subject of enunciation. — For example, with their Quebec accent, the Tremblay family says, we must find a way to push on through like our grandfathers knew how to when they fished for porpoises.[13] It’s the Tremblay family who must say this. You’ll tell me, that can be a pre-established fiction; fine, the Tremblay family are made to say that! That’s not at all the case because, at that point, [the family] is not going to reinvent the myth of the porpoise and porpoise fishing. They have to reinvent that and do so in modern conditions. So, the Tremblay family’s enunciation takes place within a statement that depends on another subject of enunciation; the other subject of enunciation is Perrault. I was asking, what is Perrault doing? He’s creating the free indirect discourse of Quebec.

Glauber Rocha — these methods are [meant] to give you an idea of the variety of free indirect discourses — what does he do? A radical critique of the myths of the colonizer, including the myth of the bandit-savior and the prophet. “The Devil,” and I don’t know what, the… “the black God,” no, “the black God and the white Devil”? … Blond? White? “The white Devil”, right? [Students assist Deleuze with the title which is Le Dieu noir et le diable blond (1964) [Black God and White Devil] And… or is it white? Blond? Anyway, I don’t recall…

Christian: Yes, but in any case, it’s a bit complicated, the translation for the title…

Deleuze: In any case, these are the two great characters that Rocha is going to use, namely, the bandit and the, and the… and the prophet, fine, who nevertheless appear to be popular myths. But he tells us: these are myths that have become dangerous because they have been emptied, emptied of their substance. That’s not what’s going to put the Brazilian regime in danger. And then he finds himself – how can I put it? – he finds himself stuck in his own way. How can we get the people to invent new myths? This is what he calls “agitprop cinema.” Rocha’s agitprop cinema is very different, it’s an Eisensteinian formula, [but] it’s very, very different from Eisenstein’s cinema. [Pause]

And until his exile, Rocha’s formula will be — and this will be a fantastic cinema — it will be: put everything in a trance, put everything in a trance, that is, translate violence, immediately translate capitalist violence into popular violence, popular violence being exercised not only against capitalism, but above all against the people themselves. Mixing all these sorts of violence, creating a web of violence, of trances. Rediscovering the state of trance in the idea that it will perhaps in turn generate a revolutionary motive, there you have Rocha’s style of agitprop cinema. I would say that he, too, creates the free indirect discourse of his people. [Pause]

And the last example I selected, yet again, is another case of free indirect discourse, it was Rouch — no, I selected many others — in Rouch’s work, that is completely different again since his first subjects of enunciation are: “Me, Jean Rouch, how am I going to be able to escape from my rotten civilization.” I don’t know where Jean Rouch comes from, but you only have to look at him to see that he’s a, that he’s a… more of a big bourgeois type than prolo [proletarian], right? Well, Rouch’s strength is that he can’t stand this civilization. How do we escape it? So, there are several… here too, this is a problem, [and] there are several solutions. We could tell him, well, join the Communist Party. [Laughter] Rightly or wrongly, he judges that this doesn’t answer his problem. For him, escaping from [civilization] means getting out of there, going to Africa. Fine, very well. That is, how does one become black? Moi un noir [1958]. The film, Moi un noir, doesn’t just refer to Rouch’s character, it refers to Rouch himself. I would say the enunciable of Rouch’s statement is: moi, becoming black.

Nevertheless, he doesn’t transform himself into a black, no, he doesn’t turn into a black. He goes a bit of the way. What’s better? What’s better than going a bit of the way? And under what condition is it good to go a bit of the way? On the condition that the other [also] goes a bit of the way! That’s starting to be a lot of bits of the way. And what is the other? It’s the Black, the Black engaged in a strange becoming. Namely, what do all Third World cinemas have in common? Third World authors explain it very well when they tell us: this is why you can’t understand what we are. That’s why we… I’m not talking about you, for those who are from the Third World, and who are able to understand, but, well, for me, what makes it so hard for me to stand or grasp a film by Rocha or a film by [Philippe de] Broca? The difficulty for us comes essentially from this: it’s precisely [that] its sense, namely the problem to which these films respond and which these films suppose, partly escapes us. Namely, what is one of the givens of the problem? Because there are givens of the problem which are not necessarily provided, which are difficult to find.

It’s like “the immediate data” in Bergson; the immediate data are neither immediate nor given.[14] This doesn’t keep him from having every reason to call them the immediate data. The data of a problem are not given! And what are the data or givens of the problem for the Third World? It is the existence of a market that is invaded by American B-movies and big production, or by [films from] the Philippines, or karate films or Indian films. I’m talking about commercial, big budget Indian films. This big budget production has a grasp on the market. Everyone says it has grasp on North Africa as well. There was a period for big Egyptian productions also, big Egyptian commercial productions for the Arab world, etc. — I always wanted to see if there are any in the… I’ve never… I’ve never… but there are cinemas in Paris that show these commercial films for Arabs and the poor; I wanted to see what this production was like — Rocha explains a lot about that, and Broca does so also for the Philippines. We absolutely cannot understand what authors like Rocha and Broca want to do if we don’t take that into account, namely that they are addressing a people, what I call “a people who are missing”, that is, a people who are literally stuffed with this cinema.

So, what do they have in mind? For them, this is a strange undertaking. It’s not about churning out films that… So, this concerns a relatively educated audience because American B movies are very, very well made. And that’s why I’ve always been surprised that great filmmakers, Third World filmmakers, have extraordinary skill [savoir], even when they’re not great. But I tell myself, hey, this is terrible, and I sensed something like I was making a critique of it. I told myself, that’s not good; they already know, but [just consider] all the tricks in the latest Godard. They know everything… all the… all the… all the… I don’t know what… ; they used all the techniques… they understood them much better. You have to admit, in fact, [that] they are already… Because for them, what are they involved in? It’s not subjective; that’s not a very good word, right, but it’s about turning the cinema that their audience is fed up with upside down to then derive something from it, to derive from it new types of statements, to create new myths, to call for a new type of fabulation.

So, fine, I come back to Rouch. Moi un noir, that means: “me, Jean Rouch, how to become black?” But the audience he’s addressing, at once fed up, and in Africa as well, with American B-movies, consists of Black people, one of whom — you recall, in Moi, un noir, in this sublime film — one of whom — I won’t say he’s taking himself to be — for convenience, let’s say, he is prey to a becoming-American-federal-agent, that is, takes himself for Lemmy Caution, whose other, the little whore from Treichville [a district of Abidjan], takes herself for Dorothy Lamour, that is, two becomings [that] intersect: the becoming, the becoming-black of Rouch and the becoming for fun, the becoming-white of the Blacks, of the Abidjan Blacks who play, if you like, at being Dorothy Lamour or Lemmy Caution, exactly as other Blacks — not exactly — play at becoming-panther, becoming-lion. The becoming-Dorothy Lamour of the little prostitute is not so, so different from the becoming that the same Jean Rouch speaks to us about in Les maîtres fous [1955] where, this time, great African myths are addressed, but about which we could say exactly the same thing that I said for Rocha just now: yes, of course, these were African myths, but today they are emptied out.

So, this double becoming, you see, allows me to say, well, in all of Jean Rouch’s work, he maintains the free indirect discourse of Africa. He absolutely needs… that’s why, when he says — you understand, when he is considered seriously — when Jean Rouch says: “I don’t have any imagination so that’s why I let my characters invent,” this amounts to saying very, very politely – because Jean Rouch is very polite, I think — this amounts to saying very politely, just back off [vous m’emmerdez], just back off with your questions. That means you haven’t understood anything! You haven’t understood anything! It’s exactly like Perrault; it’s not because he lacks imagination; it’s because there’s no other way for their cinema to work.

And so, of course, this is not necessarily so-called “lived” cinema, or “cinema verité.” I was telling you in a completely different way, filmmakers of composition like [Robert] Bresson and [Éric] Rohmer also create and also explore a free indirect discourse. And all the research today into sound, which we talked about extensively at the end of this year, presents the statements of free indirect discourse since you have seen in the cinema, or very rarely except in ordinary cinema, you no longer have statements that can be reduced, [or are] reducible to simple interior monologue. So, in fact, I insist greatly on the time-image and processes of temporalization [that], I believe, pass through these becomings involved in free indirect discourse. Whereas the movement-image could refer to the great circle and the great circulation of an interior monologue, here, there is a breaking of the totality in favor of the processes of becoming, of the processes of temporalization which means that the time-image demands a different type of statement than the movement-image. [Pause] – Yeah, is that okay? – [Pause]

And what strikes me in the same sense [is that] we could ask ourselves — we didn’t do that this year — we could ask ourselves, in fact, what has changed? Just as we looked for the difference between the so-called classical image and the modern image, we could look for the differences between classical political cinema and modern political cinema. It seems certain to me that, yes, there is an obvious change which means that the only political cinema today, apart once again from the Straubs [Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet] and [Alain] Resnais, political cinema today has shifted away from the West, from North America, and has moved into the Third World. But a profound change in political cinema was required, and as a result, we would find in the political image in cinema exactly the differences comparable to those we found between the movement-image and the time-image. Yeah. [Pause]

Is there anyone who wants to…? [Pause] What bothers me is what I’ll do next year. Well, yes, it will be less… less… Those who will be here next year, right, I’m not going to continue with cinema unless you find me some… unless you find some subjects… I don’t really know how… we’ll see. Fine. Is there nothing else? [Pause] I mean even some… What I would have liked is some critiques, critiques in the sense of, well, there’s this that we completely forgot, that we didn’t talk about at all. I’m thinking about next year. I could work on it during the holidays, [on things] that you might consider to be huge gaps, I mean, things that we should come back to more seriously.

Lucien Gouty: [Unclear comments] … the novel by Mieli…

Deleuze: On Mieli, on Mieli’s novel, ah yes, yes… yes… [15]

Gouty: That’s something we could fabulate with and then…

Deleuze: I’ll point out that next year, I was thinking of doing something because, in fact… What time is it?

Gouty: It’s five to noon.

Deleuze: In all the time I’ve been at Paris 8, and this is quite normal, I’ve changed subjects every year. And there’s nothing that great in my doing so since I’ve never taught on work I’d already completed; I’ve always taught on work I was developing. So, for me, the seminars and the work joined together, joined together wonderfully. And that allowed me to change subjects. So, it was good, it was good for me because the challenge [l’épreuve] of a course is unforgiving. For the person giving the course, [this challenge] reveals what’s missing, what holds up, what doesn’t hold up. The challenge presented by course is unforgivable, unforgivable. So, fine!

But here I am facing next year; on the one hand, next year, I can’t, I need a quiet year because I would like, I would like to get into what for me is the supreme subject of my life, to give a course on: what is philosophy? So, this course that I dream of, I don’t feel capable of offering it next year. I need a year, I need a year of work. Maybe two years. So, I’m stuck for next year, you understand? I’m so stuck that, at the limit, I would imagine a format for next year almost as topics by request, where we would do separate sessions. So, in fact, for example, you might tell me — even if it means announcing the sessions beforehand — you might tell me, “in two weeks, do what you need to for us to consider Mieli’s novel.” At that point, we would devote a session to Mieli. Or someone might tell me, [as] he said to me: “You talked about oppositions in Aristotle; can we do a session on opposition, on problems on the notion of opposition.” That’s something we could do.

Raymonde Carasco: We could undertake something on time, and precisely how time taken as fragmentary, that is, “the untimely,” “the inactual,” “the a-ternel”…

Deleuze: So, you’re right because, in fact, that connects with a topic that I treated very, very rapidly! The year took us by surprise, but I never finish what I announce. First of all, it would bring bad luck, and then, I had announced that we would get much more deeply into [Maurice] Blanchot, Blanchot and [Michel] Foucault. So, in fact, because next year [Deleuze coughs], no, I would develop that if there were some [of you] who are returning next year. Couldn’t we develop something like that, where for a year this wouldn’t be a continuous course? For one year, I need to get out of this, these sessions which are too much, which ultimately seem to me almost unhealthy, because for you and for me, they seem too much, too exasperated, too… too… I don’t know what to say… something like… it’s three hours, three hours. I sometimes wonder how you manage! Because it’s not easy to sleep either; these are not good conditions, so how do you manage three hours? I don’t know how I manage three hours. I don’t know how you manage. I think it’s as tiring for you as it is for me. But I find it… there’s something hard. I mean, there’s something wonderful in what we’re doing here, in the group that we form, but there’s also something too hard, too… I don’t know. On the other hand, not teaching is not something I can even imagine, I mean, organizing sessions like today on issues like that.

So, proceeding with topics by request might be a possible solution [since] perhaps that would break [with the past] — there are obviously too many people – all year long, we would be as we are here, the number, the number of us here; we could work so much better, it would be wonderful! [Deleuze lowers his voice and speaks for a few moments, inaudible remarks] But at that point, in fact, what bothers me a little would be the extreme diversity of the subjects. And yet, even that would perhaps be possible; they would overlap. [Pause] I would like for those who intend to come back next year to think a little about a solution which, in any case, would no longer cover a year, [but] which would no longer be the kind of seminars as I’ve offered them until now.

A student: [Inaudible remarks] … you have already undertaken a truly enormous effort to show the intersection of philosophy with other domains, and this year’s seminar on cinema was good, so perhaps next year, what remains is to offer a course on the relations of cinema with plastic arts, and the reasons … [Inaudible remarks]

Deleuze: Well, for example, but the annoying this is that I’ve already done that… [A few indistinct words] and I cannot repeat that… it’s impossible to repeat a course, it’s just not possible. I mean, about four years ago, I devoted a whole semester to color and painting.[16]

The student: [Inaudible comments]

Deleuze: Yeah, yeah, so even were I able to, that [seminar] obviously didn’t exhaust the subject, but to return again to the theory of color isn’t something I can do, because I’ve already done it. And what interests me in painting is color, so no, I can’t take all that on again. It’s done. [Pause] I tell myself, that’s my joy; we’ve really done a lot, [and] here once again, it’s not simply thanks to me, it’s thanks to you too. But you understand, what interests me in fact is talking about color, [and] well, I did it for a semester. I can’t do it anymore. However, that would interest me, that would interest me greatly, but I can’t do it anymore because of… I’m even certain that there are about ten of you here who already were involved in [that seminar] for quite a while.

Robert Albouker: [Inaudible comments] … movement-image, time-image, what was developed on Bacon and on the Figure, to return to…

Deleuze: To return in general or to a period, yes.

Robert Albouker: … on the Baroque, on the rupture of the Baroque, on the countryside in painting…

Deleuze: Yeah, but I’m going to be stuck, you know, I’m going to be stuck, Robert, because I’m capable of doing something like what you’re suggesting … My immediate reaction is that I’m only capable of doing that by taking [the topic] as an idea, as a fundamental theme to understand the movement. If I don’t talk about color in painting, I can then only talk about light. And I’ve talked about light so much. Obviously, that… But it wouldn’t be at an adequate level, it wouldn’t provide me with a continuous subject. It’s easier to do two sessions next year in which I’ll try to bring together everything we’ve considered about light because we’ve talked about it often. And I have the impression that we’ve never, we haven’t brought it together. We don’t have… and the problem of light, in fact, is also fundamentally pictorial, cinematographic, it’s philosophical, because how, doing that, it would allow me to return to this whole theme of light which is, which in my opinion defines the philosophy of the seventeenth century. It’s not by chance that they constantly use the term light. [They use] the light of evidence, they use the clear and distinct idea, you understand. It is an optical philosophy.

So that would be excellent, that would give us… Yes, you’ve given me a good idea; that’s the kind of idea I need. Yeah. That gives us a group, yes, to get back into cinema. In everything I’ve done on cinema over the last two or three years, what I care about most is the difference between German light and French light. I found that very… I found that very, very good. I found that it worked, that it was true. The French have never had a sense — and this is a compliment I’m paying them – [they] never had a sense of the struggle between light and the night. They’ve always had a sense of the circulation of solar light and lunar light. Who did that… I saw, oh yes! In Libération, in the article on [Pierre] Tal-Coat which for once was not awful, the article on Tal-Coat’s death [on June 12, 1985] in which there were extremely beautiful statements by Tal-Coat on his absolute ignorance of shadow, and the way he said: all Renaissance painting is about problems of shadow, they only grasp light in relation to shadow. And I am a painter of pure light; I have never understood shadow.[17]

And so, it seems to me very, very, very… it could, I was telling myself… and yet there is no resemblance between Tal-Coat and [Robert] Delaunay, but [that statement] could be signed Delaunay. Delaunay also knows, simply — unlike Tal-Coat who only knows one light, this is not a criticism — Delaunay knows two lights. He knows the light of the sun and the light of the moon, and from there, everything, everything enters into rhythm. But if you like, that’s also true of French cinema, that’s what strikes me, that’s what strikes me enormously. If you take a guy like [Jean] Grémillon whose lights are splendid. I understand the opposition of the entire French school to Expressionism.

Robert Albouker: [Inaudible comments]

Deleuze: What?

Robert Albouker: [Inaudible comments; answer about French painting; a question on light with the diagram]

Deleuze: You’re right.

Robert Albouker: [Inaudible comments]

Deleuze: You’re right.

Robert Albouker: [Inaudible comments]

Deleuze: You’re right. [Pause] But that’s very good, yes, but then, it would fit more into the somewhat fragmented method where we would assign ourselves a theme for two weeks. But it wouldn’t surprise me that this method could be interesting because, in my opinion, we will realize that the themes themselves, without being prepared that way, in this sense, that the themes come together, come together very… There’s music too, there are musical things; only [for] music, then with Pascale [Criton], so that goes back a very long time ago [when] we were still at Vincennes.[18] There are things I would like to take up again on music.

A woman student: There’s light in music.

Deleuze: What?

The student: There’s light in music?

Deleuze: Light, so yes, yes there is something like light, well yes. Well, those who intend to come back, during your holidays in your spare time, you’ll reflect on something to break a bit with the course style that I have used for 10 years, 15 years.

Georges Comtesse: There’s a problem…

Deleuze: Yes?

Comtesse: We would talk about something for two sessions… [Inaudible remarks] a correspondence between the very singular expectation of language as we find it in certain writings of Maurice Blanchot, very singular because we must mark this singularity, the singularity of this language. I am thinking in particular of La part du feu [1949]; I recently re-examined some absolutely extraordinary texts which are singular [a few indistinct words], and then precisely this thought of language, and then the series of four films by Syberberg.

Deleuze: Yes! Yes, since we won’t be discussing Syberberg at all, we’ll see about that next year, we’ll do a little session on Syberberg. And that will coincide with music; you’re familiar with that, Pascale?

Pascale Criton: No.

Deleuze: No, are you familiar with Parsifal?

Criton: [Inaudible comments]

Deleuze: No, no, are you familiar with the music and the libretto? Anyway, that wouldn’t take, that wouldn’t take you much time to… because that would nonetheless be something that…, yeah, you’re right…. We could go back into… That would constitute a set within a set, if only on the musical question…

Comtesse: Regarding Parsifal, as Sybergerg himself says, [he] defines cinema as the music of life.

Deleuze: Yeah, yeah, yeah…

Comtesse: [Inaudible comment] … that reflects thought.

Deleuze: We’d have to see if the same type of expression wasn’t there, you’re right, to state whether all the expressions were… [Recording interrupted] [1:48:48]

Part 3

… the same as in cinema, especially since there is the essay in Change which interests me a lot, which was translated in Change on irrationalism. So, it’s good, indeed, because in this method, I immediately tell myself [that] we could then take advantage of Syberberg’s text on the irrational and irrationalism — which seems to me to be something very poorly understood today, irrationalism — it’s a beautiful text on irrationalism, what Syberberg wrote.[19] So we do a session or two on the irrational and irrationalism in philosophy, whether there’s a tradition of irrationalism and if we could link it to Syberberg. We could approach it like that.

A student: I have a small personal wish… Is it out of the question to hold a session on another topic that was developed elsewhere, namely the desire in young readers of Nietzsche?

Deleuze: Ah well, yes! I was thinking, I was thinking that next year, I was thinking of dividing it in two since there are supposedly two sessions — or at least dividing it into two semesters — only there is one thing that I have really wanted to do for years: it is to offer a course with you [as] a commentary on the last book of [Thus Spoke] Zarathustra, not all of Zarathustra, but the last book which seems to me to be one of the most beautiful things that has ever been written, and to do a commentary in that context where you would have to read the text along with me. That could take us one semester, and then in the other semester, we’d follow this process and then, within the framework of an outline for the fourth book of Zarathustra, we could very well treat the material by posing questions, absolutely…

Christian: And if you don’t mind, what I’d like is to discuss a bit, to return to what you’ve called the third synthesis of time and…

Deleuze: Yes!

Christian: …and especially because there are things where you talk about the order of time and the series of time, but the whole of time, this action which is, let’s say, adequate to the whole of time, that’s something which interests me.

Deleuze: Yes, yes, like everyone, we all make progress; I’ve made progress since the book you’re referring to.[20] Right here, in this year’s [context], we can offer an answer to this question: this is the act of fabulation, I’d say, “this action too great for me,” it’s the act of fabulation, because the act of fabulation is constitutive of a people.[21] This is what I was getting act regarding Third World cinema: the act of fabulation is the constitutive act of a people; fabulation is the function of the poor, fabulation taken as the function of the poor or as the function of the damned. So obviously, in this sense, this breaks with the classical image of political cinema, but if the fabulatory function is the function of the poor, the act of fabulation, as we have said, is precisely “this action too big for me.” We see it very well even at the level of Quebec, this action as too big for me, for the English, for the Quebecers, in the Third World somewhere; inventing a people is too big an action, it is too big an action. And there’s the idea that we might discuss: the peoples of Latin America have to be “reinvented” or rather must reinvent themselves, the African peoples must reinvent themselves, that’s it. If we start from this idea which is definitive and seems to be part of the definition of the Third World, it is obvious that this is the type of action about which everyone can say: “This action is too big for me.”[22]

Christian: But are there any actions that aren’t acts of fabulation that we can consider as such? Because I understand that for you, it was necessary to distinguish between action cinema and everything that action becomes…

Deleuze: Yeah, there has to be some action; yes, that’s my opinion, yes, so what type of action? Yes, but we mustn’t exaggerate since every revolutionary movement today exists within the conditions to ask, “what type of action?”. What I mean with this is that one can say: “This action is too big for me,” since we can’t know. This [action] is an object of discovery since, at one point, Enver Hoxha, for example, believed, at one point believed, up to a certain point, in the possibility of this type of action, up to the death of [Che] Guevara, and then in a certain way, Latin America pursues these modes of action. What’s certain is that [Latin Americans] are looking for other modes as well, but no one will find them [since] they are to be invented collectively. This is Perrault’s very beautiful expression, “how to invent a people that already exists?”[23]

We can also point to Paul Klee’s very beautiful expression, which for me marks a turning point, and I mean [it’s] something that would define political cinema very well. He says: “the Great Work”, “the Great Work in painting” — he speaks very well of the “Great Work,” and this comes after the Soviet revolution — he says “the Great Work in painting, I see very well what it must be, and I myself have begun to sketch parts of it. We have found parts, but not the whole” — that is, no painter, no artist can make the Whole — “We still lack the ultimate power, for: the people are not with us. But we seek a people.”[24]