December 11, 1984

We seem to have fulfilled the classic image of the brain, which would consist of integration-differentiation by the centers, sensory-motor association, rational cutting. … If I tried to summarize what lived relationship we have with the brain, on the level of this image, it’s very simple, it is the brain tree, … that is, it’s a way of life, you have a tree in your head. This tree is this axis marked by rational points, rational breaks. And many people have lived with the idea and still live with the idea that their brain is a tree, that is, a centralized system, which means: center of integrations and differentiations, and sensorimotor associations, one expressing itself within the other and forming a circulation, a whole tree of the brain, a whole tree of the brain along these two axes. And, without wanting to analyze in detail at all, that poses all kinds of problems. I quote, for example, “What is the relationship between the centers and the elements? Assuming that the elements are brain cells, or nerve cells, the centers: what are these? Are they particular cells?” You sense here that there is a whole historical problem of localization exists – which I’m not pretending to address – of cerebral localization.

Seminar Introduction

As he starts the fourth year of his reflections on relations between cinema and philosophy, Deleuze explains that the method of thought has two aspects, temporal and spatial, presupposing an implicit image of thought, one that is variable, with history. He proposes the chronotope, as space-time, as the implicit image of thought, one riddled with philosophical cries, and that the problematic of this fourth seminar on cinema will be precisely the theme of “what is philosophy?’, undertaken from the perspective of this encounter between the image of thought and the cinematographic image.

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

Discussing three viewpoints on the brain (brain biology; lived relations with the brain; the brain as cinema) from which brain transformations have occurred, he pursues the biological, scientific review, and then from the lived, experiential perspective, he considers the classical, arborescent model of the brain with numerous theoretical references (cf. Jakobson on types of aphasia) allowing Deleuze to raise complications posed by this model. Then, shifting to the lived, experiential point of view, Deleuze links the arborescent model to another model from a classic perspective, that of interior and exterior milieus with details drawn from Simondon’s L’individu et sa genèse physico-biologique. With Simondon, Deleuze considers the brain’s topological structure, particularly questions of outside-inside, and then links thought of the Outside to the complementary sensorimotor axis. After the break, Deleuze outlines four lines of research for understanding cerebral linkages: the mathematical concept of Markov chains and the study of semi-accidental phenomena and mixtures of dependence and uncertainty; a second research line, within cosmobiology, of understanding the amplified fluctuation of enzymes and proteins from the perspective of the genesis of life; a third line of research (cf. Prigogine and Stengers), the thresholds at which the amplified fluctuations can be maintained in an orderly fashion; finally, the constitution of an internal milieu as an amplified fluctuation allowing the living creature, and even the brain (through hypotheses) to enter into aleatory relations with an external milieu (cf. cybernetician Pierre Vendryes). Deleuze answers the final question — how transmission occurs within the brain — with relinkages in independent series, suggesting finally the possibility of understanding cinema no longer as linkages but relinkages of independent series.

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Cinema and Thought, 1984-1985

Lecture 06, 11 December 1984 (Cinema Course 72)

Transcription: La voix de Deleuze, Laura Cecilia Nicolas (Part 1), Guadalupe Deza; correction Anselme Chapoy-Favier (Part 2), Sabine Mazé (Part 3); additional revisions to the transcription and time stamp, Charles J. Stivale

English Translation: Graeme Thomson & Silvia Maglioni

Part 1

Sorry to disturb you, but wouldn’t you say politeness is the most beautiful form of moral consciousness? Otherwise, it’s not that I think…

Anyway, so we’ve lost some time[1], but we’re going to make up for it because today we’re going to do a rather fuzzy session, since I’m not… I haven’t yet fully recovered. And this rather fuzzy session – and I have an idea that I’ll explain to you at the end of the session – concerns our last point, the last point of this program. I’d like us to get through it today, so I’ll go faster… no, not faster, not faster, no… I’ll just be a bit vaguer to save time. This last remaining point is the fourth aspect of mutation, the one that concerns the brain. So, we’ll have a chance to recap everything we’ve done this trimester, but I’m not going to recap just yet. I suppose you will recall, this was our fourth point, which would be the last one for us.

So, what has happened? “Mutation” may not even be the best word for it. It has happened in such a scattered, imperceptible way… but, as you know, because I’ve already said this, what interests me most are three points. What has changed from a certain point of view, from a triple point of view? First of all, from the point of view of the brain’s biology. This would be for the scientists, it’s one for the scientists, though I’ve never seen a case where such problems could be considered exclusively scientific. On the other hand, it’s not only from the point of view of the brain’s biology, but from that of a lived relationship with the brain. And finally, it would be from the point of view of cinema as brain or brain as cinema. I’m not saying that all cinema is brain, and all brain is cinema. But, if you remember what we’ve seen, we’ve seen certain things… for example, a cinema that could be very rudimentarily called a “cinema of bodies”. And, as I was saying, just as there’s a cinema of the body, there’s also a cinema of the brain.

So, my three points have to do with these three dimensions: potential changes, potential major shifts in the biology of the brain, potential major changes in our lived relation with the brain, if any, and potential changes in the cinema of the brain. And regarding this, as in the other cases, I try to oppose, though always very roughly, a so-called classical image, defining “classical” as vaguely as possible, and a so-called modern image, defining “modern” as vaguely as possible. This implies that if there is a modern cinema of the brain, for example, it does not proceed in the same way as what might be called the pre-war cinema of the brain. Just as brain models have greatly evolved in the sciences, this much everyone knows. But what we can all sense, even without knowing it, is that our lived relationship with the brain has also changed, at least in some cases.

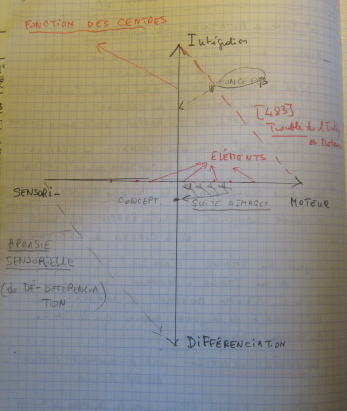

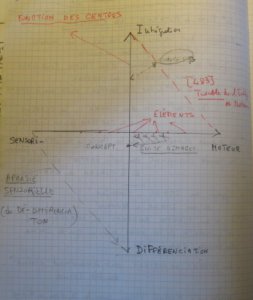

And so, I ask myself, what was the classical image of the brain? How could we present it? How could it be presented? Well, first of all from a scientific point of view. And, really, I don’t wish to say anything complicated in this regard. I would just say that in the scientific image of the brain, in the classical scientific image, it seems to me that there are two axes. One corresponds to the action of the centers, the other corresponds to the action of the elements. And it will already be quite a problem in neurobiology to know what the centers consist of and what the elements consist of, to know what their differences are, what the relations between them entail.

Suffice it to say that the centers that define cerebral areas, that define regions, cerebral areas, present themselves according to a double aspect: on the one hand… an indissociable aspect. They are “integrators”, the famous cerebral integrations. But they are also “differentiators”, differentiating areas. For example, we will differentiate between a projective area, which is to say one involving the projection of sense organs, a motor area and an associative area. But the action of integration is strictly indissociable from an action of differentiation. You see in the diagram on the board… where I’ve drawn my vertical arrow, my vertical arrow: integration-differentiation as functions of centers.

On the other hand, the horizontal arrow concerns the elements. Every element, every nerve element, every cerebral element is both sensory and motor. These are sensory-motor elements that enter into linkages or associations: sensory-motor associations or linkages, therefore sensory-motor associations or linkages that concern the elements, while integration and differentiation concern the centers. You will no doubt tell me that none of this surprises you… [Recording interrupted, 8:27]

… because in terms of the brain… we find the simplest givens of a biology of the brain, what we saw in the case of the classical image of knowledge. It’s as if there were an isomorphism between the model of knowledge and the model of the brain.[2]

Because, if you remember, when we were dealing with the model of knowledge in terms of another mutation, what did the classical image of knowledge consist of? One axis, which I called the concept axis, according to which there were concept integrations and concept differentiations and divisions, that is specifications. So, specifications and integrations which expressed the movement of the concept in knowledge. And on the other hand, there was another axis, which took the form of image associations. How did these axes relate to one another and circulate between themselves? It was very simple, and this was the model of knowledge. A concept could not be differentiated, that is, it couldn’t be divided, couldn’t be specified, without at the same time being externalized in a series of extendable images. But conversely, a series of images could not be extended without becoming integrated into a concept. Thus, we have a whole circulation taking place, which is the circulation of knowledge.

So, when I say that there exists an isomorphism in this brain model… indeed, the centers don’t differentiate without being externalized in extendable sensory-motor chains, while the sensory-motor chains are not extended without becoming integrated into the centers. So, this is normal, and it would be worrying if there were no longer this isomorphism between the old model of knowledge and the model of the brain. For reasons I don’t want to go into, I’d say that… no, I’m adding something here, but we’re still missing a point. If you’ve been following me, if you have any recollection of what we did previously, you will have realized that we’re missing a point. So, we have a duty here, but can we fill this gap? Ideally, in this old model of the brain, the cuts in the sensory-motor linkages, by virtue of the other axis, the vertical axis, would still have to be rational points.

In this way we would complete the classical image of the brain that consists of integration-differentiation through the centers… sensory-motor association and rational cuts. Now, the rational cut, I’ve already justified the first two points, but regarding the rational cut, the rational points… I haven’t been able to justify this yet. But if I could, then we’d all be very happy. So, I wanted you to feel this… if you did it would be a great joy, well, a small satisfaction anyway. But at least we’ve got the first two points.

I would say – and it’s not because of the schemas – but if I were to try and sum up the lived relation we have with the brain, in terms of this image, I would say it’s quite simple: it’s the tree of the brain. You might say, but it doesn’t look like a tree. Well, actually, it does look like a tree but we’ll see in what way. In other words, it’s a way of life: we have a tree in our head. This tree is our axis marked by rational points, rational cuts. And many people have lived according to the idea, and still live according to the idea, that their brain is a tree, that is, a centralized system. And by centralized system we mean a center of integration and differentiation, along with sensory-motor associations, each expressing itself in the other, and producing a circulation, a whole arborescence of the brain, a whole arborescence of the brain along these two axes.

Now, without wishing to analyze this in any detail, it poses all kinds of problems. For example, what is the relation between the centers and the elements? Assuming that the elements are brain cells, or nerve cells, what would the centers be? Would they be particular cells? This will be… you can see how there’s a whole historical problem of localization – which I don’t pretend to tackle now – of cerebral localization. But the problem is very, very complicated for a very simple reason. A great neurologist, a neurologist and psychiatrist, who had been greatly influenced by Bergson and whose name was [Constantin] Von Monakow, wrote an admirable book which I don’t think is read any more, a very, very fine book… M-O-N-A-K-O-W. He said: you understand, the mistake is to look for a spatial localization of the centers. The sensory-motor cells, yes, they have spatial localizations. But the integrating and differentiating centers have no spatial localization. And he proposed the idea of chronogenic localization, a chronogenic localization. So, he came up with some very complicated schemas. You can see why he was Bergsonian: he played with a kind of Bergsonian idea of durée inscribed in the living being and in the brain, and chronogenic localization was one of Monakow’s most complex ideas.

To give you an idea of the difficulties involved, I can say that a famous notion was put forward by a great neurologist named [John Hughlings] Jackson, the idea that brain diseases were in fact processes of disintegration, of dissolution. That is, the centers were damaged and, as a result, sensory-motor associations were unshackled from the centers’ integrating role. This is what he termed “dissolution”. And dissolution was the opposite of evolution. Evolution went from the elements to the centers.

What created the complications and made it so… Jackson said something very odd. He said that the centers are the least organized. In other words, the elements are much more organized than the centers, which seems strange. The centers, both integrators and differentiators, are much less organized. He explained very well what he meant by “less organized”. He meant that their organization continues throughout life. It was a way of linking up with Monakow’s chronogenic localization – not linking up, because it’s actually Jackson who precedes Monakow in history… – but in this way he anticipated the idea of chronogenic localization. The centers never ceased to establish and organize themselves throughout the whole of their life. So, they were less organized than the sensory-motor axis pertaining to the elements.

And again, you see how Jackson, in his theory of evolution and dissolution, was able to say that evolution proceeds from the most organized to the least organized, and dissolution the reverse, since the most organized is automatic: the automatic sensory-motor linkages. And so dissolution goes from the least organized to the most organized, just as evolution went from the most organized to the least organized. Nonetheless, it seems to me that in his conception he placed particular emphasis on the integrating role of the centers.

But here’s where I say it gets very complicated: in my view – and it’s just my view– there can be no phenomena of disintegration without correlative phenomena of “de-differentiation”. Therefore, patterns of dissolution become enormously complicated. There is no disintegrating action that is not accompanied by a de-differentiation, meaning a suppression of differentiation. And then, much more, perhaps, in phenomena of dissolution, there are disorders where disintegration is prevalent, and others where de-differentiation prevails. All of which considerably complicates our schema. So much so that the sensory-motor cells escaping from the centers disintegrate at the same time as they are de-differentiated, that is they lose their differentiation at the same time as they lose their integration. Hence, if I may jump now to a very famous problem, which has been quite decisive in brain mapping, this would be aphasia and the different types of aphasia. Aphasia, as you know, is a language disorder resulting from brain damage.

Now, traditionally, the great theory of aphasia distinguished – it went very far but it’s understandable, considering how complicated the axis already was – the great theory of aphasia distinguished between six types of aphasia from which, in the end, we could identify two major poles. And you’ll find a fairly detailed linguistic study of the two main poles in the work of [Roman] Jakobson. Which is a way of suggesting that Jakobson, in a certain way – implicitly, since he doesn’t claim to be a biologist – retains… [Recording interrupted; 22:57]

… but they can be reduced to two poles, two poles he studied in particular in his Essais linguistiques.[3] And these two poles will be self-explanatory, and we’ll see how they take into account our axis, or rather our two axes: a vertical axis and a horizontal axis. The two poles, he says, the two main poles of aphasia are first of all disorders that could be called “similarity disorders”, and then “contiguity disorders”. Similarity, he says, is the basis of what he calls “metaphor”, while contiguity is the basis of what he calls “metonymy”.

And if I briefly summarize these two disorders, the first, called similarity disorder… how does it manifest itself? The subject has retained the power to combine the elements of language. But what have they lost? They’ve lost… they have kept the power of combination, but they have lost the power of selection. They can construct a sentence but can no longer select between one element and another. What does, this imply? In a conversation, they respond very well, they can continue a conversation, or if presented with a fragment of a word or a fragment of a sentence, they can complete it very well. So, they’ve retained the art of combination. But they have a problem, which is obviously how to begin a sentence, it’s the initial word. Why is this? You can sense it. It’s because the initial word is something you have to select, you have to choose it. So now they are troubled. They are blocked. But once the phrase has begun, everything is again fine. There’s another moment that troubles them, however. It’s when they must select between two possibilities. For example, if they use the word “single”. For a normal person, the word “single” can be replaced with the word “unmarried”. But they can’t select, they can’t make this substitution. If you ask them what a single person is, they panic. They know how to construct a sentence with “single”, they know how to combine, but they no longer know how to select. And yet, as Jakobson would say, these are the two great poles of language: combination and selection.

What’s more, they can’t make the minimum selection of the type: A = A, or if you prefer, the minimum substitution, the identical substitution. Because if you say to them: “Say no”, they will reply: “No, I can’t”. It’s a seemingly paradoxical situation, since they can’t say “no”, but they say they can’t do it by saying “no”. You see, this actually concerns two very different axes of language. If we say to them: “Say no”, that is: “Repeat” – a substitution of the type A = A – they reply: “No, I can’t”, “No, I can’t say no”. The “no” they use in “No, I can’t”, is caught up in a combination, therefore it’s something they can do, whereas the selection of “no” and the minimal substitution of “no” by “no” is something they are unable to perform. It’s a type of aphasia, an aphasia of similarity or similarity disorder.

In contiguity disorder, the opposite is true. Similarity seems to be saved but composition is… selection seems to be saved but composition not in the slightest. In this type of aphasia, you encounter what linguists call “agrammatism”, that is, the dissolution of grammar. The sentence of this type of aphasic – you can see that it’s very different from the other case – the sentence of this type of aphasic ends up being a kind of fragmentation of words. What disappears are the links between words, and in particular inflexions. When they use a verb, this type of aphasic generally puts it, or would very often place it in the infinitive. Right. This time, as Jakobson says, similarity is saved. They can say the word “pencil” very well, they can make the necessary substitutions, but they can no longer make the combinations.

Well, to sum up very quickly – because I don’t want to dwell on this, I need to make up for the time I’ve lost – I’d say this: what is contiguity disorder according to Jakobson? Here, I’m speaking for myself, I’m no longer speaking according to Jakobson. Jakobson distinguishes very… I’ll come back to Jakobson quickly, he distinguishes perfectly between the two disorders by saying that the “contiguity disorder”, that is, when what is disturbed is the power of construction, is a disorder that relates above all to the message. Similarity disorder, on the other hand, is a disorder that primarily concerns the code. That’s easy to understand. When he’s more precise, because the interrelation between the code and the message is such that he indeed feels the need to be more precise, he tells us that similarity disorder is first and foremost a decoding disorder, and that contiguity disorder is first and foremost an encoding disorder. And in fact, anyone who’s studied even the least bit of linguistics will know all this.

As far as I’m concerned, I’d just like to draw the following conclusion: contiguity disorder is above all a motor disorder – you’re following my schema… “motor” is M, there, on the horizontal axis – it’s above all a motor disorder. In fact, it concerns the construction of spoken sentences and the combination of elements. And above all, it’s also a disintegrating factor. Why is that? As we’ve seen, it’s a disorder that concerns combination, and combination should be understood in two ways: combination of a linguistic unit by sub-units, by inferior units… by inferior units I mean, for example, phonemes, phonemes as sub-units in relation to morphemes – so a disorder of the combination of a unit by sub-units – and the combination by which a unit enters into superior units. It’s therefore a motor and integration disorder. Which is perfect for me, since it would allow me to draw a dotted line from I [Integration] to M which would represent this disintegrating motor aphasia. And motor aphasia was a common term in 19th-century aphasia theory.

The other disorder, similarity disorder, is essentially a sensory and differentiation disorder. Why? And what does it concern, exactly? As I said earlier, just as there are two levels of integration – the integration that a unit effects in relation to sub-units, and the integration into which it enters in relation to a higher unit – so too are there two aspects of differentiation. This can clearly be seen in language. There is a first aspect of differentiation, which we might call the discernment of distinctive features – I’m going quickly here because it doesn’t really matter, I’m only speaking for those who have studied a bit of linguistics – a phoneme is a carrier of a plurality of linguistic features, of distinctive features.

For example, when I say the word “cochon” [pig], I can extract the phoneme “ch”. Well, “ch” is, as linguists say, a cluster of distinctive features. Why is that? You’ve got “ch” rather than “t”, “cochon” rather than “coton” [cotton], you’ve got “ch” rather than “s”, “cochon” as opposed to “cosson”, you’ve got… Let’s look for other examples, what could it be? “Colon” [settler]… ah, yes, “ch” rather than “l”, “cochon” instead of “colon”. Each time you have… there isn’t a phoneme that doesn’t constitute a set of distinctive features. So, the first aspect of differentiation, I would say, is the selection of distinctive features, or rather… no, it’s the discernment, it’s the discernment of distinctive features. And the second aspect of differentiation is the substitution of two formulas that differ in one aspect and resemble each other… the substitution of one for the other two formulas that differ in one aspect and are similar in another.

It must therefore seem obvious to you that the kind of aphasia which presents phenomena of de-differentiation is also a sensory aphasia, while the aphasia which presents features of disintegration is necessarily a motor aphasia. So, my two types of aphasia, you see… I could draw a line going from I to M, that would be a disintegrative motor aphasia – and what I’m telling you now is no longer Jakobson, it doesn’t matter… but let’s not attribute it to him, he wouldn’t be happy – and the other aphasia S [Sensory] D [Differentiation], this would be the sensory aphasia operating by de-differentiation. That would be very complicated. What I’d like to show is that, in terms of the classical theory of aphasia, there are other types of aphasia that would allow us to fill in other blanks, but it wouldn’t give us much satisfaction. So, I’ll leave it at that for now. I hope you will vaguely remember this, or at least try to remember something of it, however vaguely.

I would say, well, basically, this would be the classical image of the brain. I used the example of aphasia because, on the one hand, I’m pleased to note that linguists… do you know what they’ve done? They’ve absolutely stuck to… in this new discipline, they’ve stuck to the oldest cerebral schema. So, I’m only mentioning the greatest among linguists. I’ve just tried to demonstrate this in the case of Jakobson, but for [Noam] Chomsky, I’d have to show it in detail, and it would take us three hours, but that’s all right. In Chomsky’s case, it truly is astonishing. Moreover, he admits it himself. When he made his return to Descartes, it wasn’t by chance. The cerebral model, that’s what interests me about linguists, knowing exactly what is the underlying cerebral model that they’re using. I believe that linguistics has an absolute need of a cerebral model and that it elicits it, it elicits and deploys it implicitly. So, when we turn to speak a little about these questions in terms of cinema with regard to linguistically-inspired semio-criticism, a principal question would be, for example, thinking of the very rigorous and important and highly interesting studies made by Christian Metz… What cerebral model does his conception of cinema imply?

And what strikes me about linguists in any case is the extent to which they cling to this conception of the brain: integration-differentiation of centers, sensory-motor association of elements. You might say, there’s no harm in it and I’m not saying that there is. There’s nothing wrong with it. It’s just that here we have a new discipline operating with an old cerebral schema. That’s all there is to it. I’m only rejoicing out of pure spite. Well, it strikes me that Jakobson’s conception of aphasia is very, very strong. You should read the book, because all these courses are designed to make you want to read this or that text. You’ll see, you’ll see for yourselves, but it’s no accident that he finds exactly the same schema of the various aphasias as that proposed by 19th century neurobiologists. And this concludes my first point.

I would say that what we have here is basically… basically, it’s the brain considered as a tree. Well, we live like that, or at least, we’ve lived for a long time like that, our fathers lived like that. It’s funny, imagine living… here, I’m talking about lived experience, I’m jumping to lived experience. I’m not saying much. But these are people who live with a tree in their head. There are a lot of people like that. And it’s no coincidence that the tree is both the model of the brain and the model of knowledge, from the tree of knowledge to the tree of the brain. Okay, short parenthesis.

What’s changed? I see two points of mutation, two points of mutation, but again, they overlap so much, it’s a very intricate, an extremely intricate business. I would also say that… to be precise here I have to go back… as well as being an arborescent system, I would say that this cerebral system is also a centralized system. It’s a centralized system because the whole vertical axis is based on the centers while the circulation is based on the interaction between these centers and the elements. Is that clear? So, it’s an arborescent, centralized system.

So now we’ll move on to the research into our mutation with the precautions I’ve taken. Bear in mind that it didn’t happen all at once, it occurred a little at a time. Let’s go back to the integration-differentiation axis, and here I would say that already in the oldest biological theories, and notably in the work of the great Claude Bernard, the problems of integration and differentiation have taken… have found themselves inexplicably tied up with another type of problem. And although the two were closely linked, they didn’t constitute the same problem. The other problem that intersected with the question of integration and differentiation was that of external and internal milieus. The more complicated and complex living beings became, the more they were composed of internal milieus. The stronger and more structured these internal milieus were, the more they depended on cerebral mechanisms and cerebral regulation. What’s more, organic differentiation and the organization of internal and external milieus intertwine at every moment. This means that the distinction between external and internal milieus promotes and accelerates the processes of organic differentiation that it, at the same time, implies. Here, too, there is complete interaction between differentiation and the constitution of internal and external milieus.

So how do integration and differentiation come about? Among other things, they arise through relative levels of exteriority and interiority. Why do I say relative? Because, at first sight, there are no absolute external and internal milieus. What from one point of view is an internal milieu becomes an external milieu from another. It all depends on which organic unit you take into consideration. You can, of course, take the organism as a whole, but even that will present difficulties. If you take the organism as a whole, you’ll tell me it’s not complicated: the internal milieu is what is inside. What is it that defines an evolved organism? Precisely the fact that it has constituted an internal milieu. What does it mean to constitute an internal milieu? It means constituting a milieu that no longer depends on variations in external milieus. A self-regulating milieu. For example, the heat of the blood becomes independent of variations in the external milieu. You have an internal milieu.

If you take the organism as a whole, you might say, Well, it’s not complicated; the internal milieu is everything that’s inside. But there’s no guarantee. We can’t be sure. What would you say about the stomach? Is it an internal milieu? Yes, it’s an internal milieu, but up to a certain point. In relation to what is it internal? Because in relation to something else it may be external. From another point of view, an internal milieu can be an external milieu, which we will call an external milieu annexed to the organism. All the more so for the intestine. The intestinal milieu is an internal milieu. But from another point of view, it plays the role of an annexed external milieu. So much so that intestinal waste is indeed discharged into the external milieu.

There’s a text by [Gilbert] Simondon in his very fine book, L’individu et sa genèse physico-biologique [The Individual and its Physical-Biological Genesis] [4] that emphasizes this point well. Here is what he says, and he says it better than I can, so I might as well read it to you: “There are several levels of interiority and exteriority; thus, a gland with internal secretion discharges the products of its activity into the blood or into some other organic liquid: in relation to this gland” – in relation to the gland with internal secretion – “the internal milieu of the general organism is in fact a milieu of exteriority. Similarly, the intestinal cavity is an external milieu for the assimilating cells that ensure selective absorption along the intestinal tract. […] The space of the digestive cavities constitutes an exteriority in relation to the blood that irrigates the intestinal walls. But the blood is in turn an external milieu in relation to the glands with internal secretion, which pour the products of their activity into the blood.”[5]

So that’s all I want to say. And here too, I don’t have time to develop because… The hypothesis I’d like to advance is that processes of organic integration and differentiation are strictly inseparable from the distinctions between internal and external milieus – these distinctions remaining relative, strictly relative, which means that a milieu said to be internal from one point of view will be external from another point of view, and that there will be a whole chain of internal and external mediations. These distinctions between internal and external milieus remain relative as long as we relate them to the integration-differentiation axis. So the integration-differentiation axis passes through these distinctions, which are relative to it. Okay, that must be very clear because…

All right, then. But that doesn’t prevent us… Simondon adds in some very, very strange passages that I nonetheless find quite admirable… if we refer to the state of the simplest organism, the simplest organism… this is all quite tedious, but thanks to Simondon the conclusion will be beautiful. If we look at the simplest organism, what happens? The simplest organism, undifferentiated and unintegrated, enjoys absolute interiority and exteriority, which are distinguished by what? By a polarized membrane, the simplest expression of life. There’s the outside and there’s the inside. In other words, the simplest organism is arranged according to an absolute outside and inside. As organisms become more complex, that is, as they integrate and differentiate, they pass through relative levels of interiority and exteriority.

That leaves the third conclusion, which you can work out for yourself: the brain restores, in its own way, an absolute outside and inside which is like the limit of all relativity of the external and internal milieus. What does this mean for the brain? Well, the brain will bring into co-presence an absolute inside and an absolute outside. What do I mean by co-presence? They will be in contact, in contact without any distance between them. In this way, outside and inside are no longer relative. The brain restores an absolute outside and inside, in other words, that which pertained to the simplest organism. It restores it in its own way. It brings into contact an absolute outside beyond all external milieus, which will undoubtedly be like the horizon of all external milieus, and an absolute inside, beyond all internal milieus, which will undoubtedly be – how shall I put it, poetically speaking – the most bottomless, or the deepest, of all internal milieus.

The brain will bring into contact an outside deeper than all external worlds, an inside – you can see where I’m going with this, if you remember what we did earlier – and an inside deeper than all internal worlds and milieus. How does it produce this contact, a contact without distance between outside and inside? The elementary organism required a distance between its absolute interiority and its absolute exteriority. What does contact without distance mean? That’s what Simondon explains in these wonderful passages. It means that the brain has a topological structure… [Recording interrupted; 58:10]

Part 2

… The brain has a topological structure that ensures the co-presence of an absolute outside and inside. You might ask what this is. What does it mean? Well, okay… There are just two things I’d like to point out here. As far as I know, even neurobiology has nothing to say on the matter, and it took a philosopher with great expertise in biology, technology and cybernetics to remind us of it, because I have the impression that cybernetics is very much concerned with this question. In the end, as Simondon says, the brain has no Euclidean interpretation. The brain cannot be interpreted in Euclidean space. Integration-differentiation can be interpreted in Euclidean space, and so too can relative internal-external milieus. But what does the brain imply? A topological space.[6]

But let me quote an interesting text here: “The development of the neocortex in the higher species takes place essentially through a folding of the cortex: it’s a topological solution, not a Euclidean solution. Ultimately…” – I think this text is very fine, it’s not important if you don’t understand much – “Ultimately, we shouldn’t talk about projection regarding the cortex” – he’s referring to what I told you about earlier: the areas of sensory projection, that is, the projection of the sense organs into cerebral areas – “Ultimately, we shouldn’t talk about projection regarding the cortex” – and, indeed, there isn’t a biologist in the world who doesn’t know that the supposed projection of sense organs onto a cerebral area are crude, senselessly crude schemas – “we shouldn’t talk about projection regarding the cortex, although there is, in the geometrical sense of the term, projection regarding small regions. We should rather speak of a conversion of Euclidean space into topological space. The basic functional structures of the brain are topological; the bodily schema converts these topological structures into Euclidean structures through a mediate system”.[7] By mediate system he means through the mediation of relative internal and external milieus.

And what does that mean? What does it imply? It means to bring into contact or into co-presence an interior that is deeper than all relative internal milieus, and an exterior that is deeper than all relative external milieus. That would be it. That would be the topological function of the brain. You see… this allows him to say: “The non-topological structure of integration and differentiation, the non-topological structure of integration and differentiation appears as a means of mediation and organization”– which is to say, of mediation and organization thanks to the relative internal and external milieus – “appears as a means of mediation and organization to support and extend the first structure” – that is, the topological structure – “which remains not only underlying, but fundamental.”[8]

Now this makes me very happy because it confirms, though using completely different means…We’ve been turning round and round this question – when I recap on all this next time, you’ll see, you’ll remember everything we’ve seen about this mutation of thought, insofar as it becomes a thought of the Outside, but of an Outside that is deeper than the external world, and which is also a thought of the inside, but an inside deeper than any internal milieu. And here, in terms of the brain, we find exactly the same problem, at the level of a topological relation, between an absolute outside and an absolute inside. In concrete terms… you will no doubt tell me that you’re begging for something more concrete, but what does that mean? It means something very simple. It means: the more an organism is evolved and subjected to a structured brain, the more the totality of its past, that is, the absolute inside – the absolute inside being precisely the All of the past – the more the totality of its past is brought into topological contact, without distance and without delay – topology ignores distances – without distance and without delay with the opening out of the future, that is, with the absolute outside.

Understand what this means. But that’s the way it is with living beings. It’s even what distinguishes the living from the crystal. When a crystal grows, what matters? It’s the molecular layers: they’re relatively internal and external. In other words, the molecular layer that has already formed is called the internal layer, while the molecular layer that is in the process of being formed is called the external layer. Well, you can empty the crystal of most of its internal substance, and it won’t change a thing. You cannot prevent it from growing. On the contrary, you cannot empty an organism of its internal substance. Its internal substance concentrates and condenses the whole of its past. And it’s this all of its past, the Whole of this past, which is in immediate contact, that is, topologically, which is – how would we say it in topology? – which is in the vicinity, independently of any distance, which is in the vicinity of the absolute Outside, that is, of the horizon of the outside world.

Therefore, we would have to say that the brain topologically reconstitutes the ordinary conditions of the simplest organism. But it is precisely in order to find them topologically that the highest complexity is required. Co-presence – even if we will have to justify it later, but we have all year to do that, don’t we? – co-presence that I could say, I could say from that point on the brain, being topologically interpreted – and it must be topologically interpreted, it can only be interpreted topologically – the brain would present itself as “contact without distance” or “co-presence” of outside and inside, of empty and full, of past and future, of front and back, and so on.

You have to hold onto these formulas, of the full and the empty. You can see that here I already have a cinematographic afterthought. What is fuller than an empty image in cinema? An empty space in [Michelangelo] Antonioni is a full image, an empty sky in [Jean-Luc] Godard is a full image. But full of what? [Recording interrupted; 1:07:19]

… no longer defined along an axis, it will no longer be defined… I don’t mean that it’s mutually exclusive, it’s not that one is false and the other… But the fundamental thing will no longer be an axis of integration-differentiation, it will be a co-presence of an absolute Outside and an absolute inside, of void and plenitude, of a front side and a reverse side and so on. If you experience your brain in this way – it’s not even necessary that you understand… – but if you experience your brain in this way, if you experience it topologically, and no longer in terms of integration and differentiation, well, in that case you will no doubt feel that you no longer have the same relationship with it, wouldn’t you say? Is it possible to experience it in such a way? Well, that’s something we’ll have to see… But it’s not easy. Do you insist on living according to a form of integration-differentiation? If so, are the gaps the same in both cases? What will the implications be for our conception of aphasia? But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

I would say, and you must sense it yourselves, that this is not sufficient. A second, a second small mutation is required. A second small mutation because, otherwise… Fortunately, this time it will be much simpler, because the first one was quite complicated. For those who want to look further in this direction… the relevant pages are… from 257 onwards…[9] So, now I would say… you see how I’ve just dealt with my vertical axis… and now we’re going to replace my old vertical axis of integration-differentiation will a topological axis. Do you follow me? And, as I said, I need a second mutation because we now have to deal with the S – M axis, the sensory-motor axis, the associative axis. So, this is something that works by itself.

How does the sensory-motor axis present itself? It takes the form of a brain cell, or nerve cell, called a “neuron”. A neuron – I’ll give it to you, for those of you who haven’t… let me remind you of the basic vocabulary… I’m using it at the level of the most basic terms – a neuron is a cell, a brain or nerve cell. This cell has extraordinary branching extensions. These extraordinary branching extensions are called “dendrites”, D-E-N-D-R-I-T-E-S. You have your nerve cell, your neuron, and then it has extensions called dendrites. So, dendrites are branching extensions that receive nerve impulses. To give you an idea of just how complicated this is, it’s incredible how many dendrites a neuron has. It has a huge number of dendrites. But there’s much more to it. There are some that extend very far, that extend extremely far. This is where things get complicated.

And then, finally, you have the third major element, the “axon”, the axon, the axon: A-X-O-N. The axon is also an extension. But this time, it’s a single extension of the neuron, a single extension that branches off at the end – so it can branch off a lot – which branches off at the end and transmits the impulse. To what? The simple answer would be: to the dendrites of the following neuron, the next neuron. It all depends. Or it might not be to the next neuron, it’s not fixed since there are dendrites that extend considerably. So, you must realize, then, that this isn’t just automatic, that any one of your neurons may sometimes be subject to very distant impulses. There’s a multitude of impulses being triggered at the same time. It’s… it’s a whole system.

For a long time, the classical image of the brain was that all of this formed a continuous network. But it soon became evident that this network was not continuous, in the classical sense of the word, but was riven with cuts. These cuts were established, for example, between the end of the axon of neuron A and the end of the corresponding dendrite of neuron B. Remember? The affected dendrite receives the impulse, transmits it into the cell, into the neuron, which sends it to the axon, which passes it on to the dendrites of the next cell. However, between the end of the axon of cell A and the dendrite of cell B there is a cut. The network is not continuous.

But for a long time, the cut was conceived, so to speak, in an electrical manner, that is, from one edge of the cut to the other, the transmission of the impulse was electrical. This cut has a name, it’s called a “synapse”. A synapse is the communication, in the simplest case, between the end of an axon and the beginning of the dendrite of the next cell. So, we can literally say that a synapse is a cut-point. That’s why, very often in textbooks, you will see the synapse defined as a junction point. It’s the point where two neurons meet. It’s a point or a cut. We shouldn’t be surprised by this, given what we’ve seen and done previously. So, we’ll say it’s a cut-point.

So, as long as there was transmission, the hypothesis of electrical transmission, everything was fine. Everything was fine, or relatively fine. There was no longer a continuous network, but the impulse could nonetheless easily cross the cut-point. Why was this? Because, at the moment of passage of the impulse, the hypothesis was that the two cell membranes, meaning the dendrite membrane and the axon membrane – or rather the reverse, the axon membrane and the membrane of the following dendrite – came together, became adjacent, became adjacent… or even, according to a particularly audacious hypothesis, formed a single membrane. Whether they are adjacent or form one and the same membrane, here again we have, we have every reason to rejoice because in my view, by virtue of what we have seen previously and without in any way forcing the issue, we are entitled to say that in this case we have a rational cut-point.

So, without forcing the issue, without resorting to a facile mathematical metaphor – because, if you remember, this was our starting point, you have to remember this, otherwise it’s a disaster. What we called a “rational cut-point” on a straight line, on a continuous straight line, was a point that operated through division into two sets, but such that this point formed either the end of the first set or the beginning of the second set, meaning that it pertained to one or the other of the two sets, or else belonged to both at the same time… If someone tells me that in an electrical transmission, the two membranes become adjacent, I would say that one marks the end of the first set and the other marks the beginning of the second set. This is a typical cut-point. The synapse is a rational cut-point. And if someone says to me that a single membrane is formed, I say, Fine, the cut-point pertains to both sets. It’s a rational cut-point.

This gives me the third aspect of the classical image of the brain: a process of integration-differentiation exercised in relation to, second aspect, exercised in relation to sensory-motor linkages, the points – and this is the third aspect – the cut-points of these linkages being rational points, meaning that the synapses are rational points. I’m laughing to myself a bit because here I am subjecting you to a very unpleasant regime that goes from rudimentary mathematics to rudimentary biology, but I hope you will understand that all this is just a way of fashioning philosophical concepts, it’s just material… Do you follow me? I’d say, here are the three aspects, including the one I was missing. It’s curious how all this can be a source of deep satisfaction. We now have a third aspect, the one we were missing, and now we have it. We’ve reintroduced rational cut-points in the brain, or into the brain-tree. And so now this gives us an overall picture of the brain as tree.

So, this great mutation no doubt occurred when doubts began to arise, not about the existence of a continuous cerebral network – that question was settled, the existence of synapses was proven, nobody could argue about that – but about the way synapses actually function. And when the doubts multiplied about the electrical transmission hypothesis, a completely different hypothesis emerged: the idea of chemical transmission. What does this mean? It means that – you’ll immediately understand the difference – when the impulse arrives at the end of the neuron in cell A, neuron A… well, there’s no adjacency of membranes, no membrane unity. It finds itself before a cleft, it has a cleft to cross. Imagine – now you’re thinking things are starting to liven up – imagine that our brain will be populated with… well with what? It will be populated by millions and millions of little clefts, synaptic clefts. Well, you’ll tell me: It was already… there were already cuts. Well, okay. What’s going on here? In the words of a very fine author, there is a “critical gap”. Between two neurons, a critical gap.[10]

How does the impulse… if the impulse lacks the power to transmit itself electrically, how will it manage? In science, to transmit something electrically means by way of charged ions, right? If this is not the mechanism by which the synapse functions, then how does it work? Well, we might begin to suppose – and we have good reason for doing so – we might begin to suppose that the impulse, when it arrives at the end of the neuron, will release something that belongs neither to it, the axon of A, nor to the other, meaning the dendrite of B. It will release a chemical substance more or less similar to hormones: a chemical mediator, a chemical mediator. But where does this chemical mediator derive from?[11]

Fortunately, with advances in microbiology, bizarre vesicles, small vesicles, have been identified in the synaptic cleft. So, you see? From there, we can assume that these vesicles contain the chemical mediator and that when the impulse reaches the end of the axon of neuron A, when the impulse reaches the end of its path, the vesicle will release a quantity of the chemical mediator. This is getting more and more interesting, because if it is these vesicles that are releasing it, the release of the mediator will itself not be continuous. There will be discontinuities everywhere. A vesicle will contain a very small quantity of neurotransmitter, a chemical mediator of the hormonal type. It will release it. So, the chemical mediator will be released in discontinuous quantities corresponding to the different vesicles that release it. This is why neurobiologists speak of “quanta”. The chemical mediator operates in discontinuous quanta. And it is via the chemical mediator that the impulse will pass from neuron A to neuron B.

What does this tell me? I don’t need to… The cut-point, the synapse, remains a cut-point. This cut-point determines two sets: neuron A, with its axon and dendrites, and neuron B, with its dendrites and axon. The cut-point determines two sets. Only, it’s no longer part of either of the sets it determines: it’s autonomous. This is not a metaphor, it’s literally what we call an “irrational cut”, which is to say, a cut that determines two distinct sets, and yet belongs to neither of the two sets. I’d say that in the case of chemical synapses… whilst in the case of electrical synapses we were dealing with rational cut-points, in the case of chemical synapses we are faced with irrational cut-points.

And then… and then, it’s the whole cerebral regime that passes under a new regime that is literally – we’ll see where it leads us – a probabilistic regime. In other words, under a probabilistic regime, what are the probabilities that a message or an impulse arriving via the axon of A will cross the critical gap, given that, at the same time, all kinds of other messages, all kinds of other impulses are arriving via other dendrites? The more chemical the synapse, the more the brain ceases to be a determinate system and becomes a probabilistic one. An American scientist entitled one of his articles – as usual, you’ll have to pardon my English – “An Uncertain System”, a system of uncertainty, a probabilistic system. Let’s say, for the moment… we’ll see that it’s not precisely this, but we’re making slow progress. A probabilistic system, fine.[12]

From the moment there is a critical gap to cross, we’re forced to switch to a kind of aleatory mechanism, which is the mechanism of the chemical mediator and the number of quanta it will release. Given that the brain is besieged by messages coming from all these dendrites, that it’s perpetually… each time there is a cut in the form of these irrational cut-points, you arrive at the question of how the linkages are made. How are neurons linked together? The answer is that linkages are no longer determined, as they were in the electrical mode. The linkages become probabilistic. But what is a probabilistic linkage? What do we mean by a probabilistic linkage?

For the moment, let’s just retain two conclusions: in what form do the two points of mutation in the cerebral model take place? The brain implies, or the brain fosters – yes, that’s even better – it fosters a space, or no, it develops, yes, develops, no… well, whatever, any word – develops a topological space and envelops a probabilistic space. So, in place of the vertical axis of integration-differentiation, we substitute the topological contact of outside and inside. For the horizontal sensory-motor axis, we substitute the probabilistic character of linkages since linkages are interrupted by irrational cut-points. In these two ways, we can no longer – if we think about life – we can no longer experience our brain in the manner of a tree, we no longer have a tree in our head: that’s all over. It’s finished.

A brain specialist… you’ll find a lot of information on synapses, for example, in Jean-Pierre Changeux’s well-known book, L’homme neuronal [1983], and you’ll also find information focusing more on the probabilistic aspect of the brain in the work of an American neurobiologist called Steven Rose, R-O-S-E like a rose, whose book The Conscious Brain was translated into French a few years ago by Editions du Seuil.[13] And in Steven Rose’s book, there’s a very interesting metaphor. He says: You understand, there are very special cases where an axon… because in each case he tries to assess the probability of the message or impulse passing. He says that this varies according to several factors. There are, for example, cases where the dendrite of neuron B… the dendrite of neuron B winds… winds around the axon. Can you see it? It coils. Now, dendrites all have spines. So, on each spine of the dendrite, there’s a synaptic junction, there’s a synapse.

So, in the case of a single dendrite and axon, you can have a multiplicity of synapses, when the dendrite coils with its spines. And then the metaphor – today what I’m saying may sound rather dull, but at the same time it’s always a source of small joys – where Steven Rose says something quite wonderful. He says: “It’s just like when”– wait… I have to remember the quote… – “twisting around each other like bindweed around brambles”.[14] That’s beautiful! And it’s going to come in handy, because it’s not a metaphor. The bindweed, you see, is a weed. The bindweed wraps itself around the bramble, and the bramble is exactly the dendrite with its spines. If I drew you a picture of a dendrite… but you can imagine it for yourselves, an extension with spines. This particularly bizarre dendrite wraps itself around the axon of the preceding neuron, and at each point of spinal contact, there is a synapse. So, the dendrite is the bramble, and the axon that coils, is like the bindweed that coils around the bramble. How far we are from the tree model! We’re in a completely different field.

In other words, feel, feel the world of the future, it’s not a tree we have in our head, what we have in our head is grass! And this is the way we must live, through a lived relationship with the brain. When I say “lived relationship”, I’m thinking of a great author, Henry Miller. He had a prodigious gift: he always lived his brain as though it were grass. Very interesting, though it’s not just an image. He lives as though the inside of his head was filled with grass. Americans are very good at this. Americans, it’s well known, don’t believe in trees, they believe in the prairie so… Well, they’ve always experienced what’s going on in their heads as grass. Ever since one of the greatest poets… since the… since America’s founding poet, that’s the way it has been.[15]

It’s very odd. And when… and when Miller asked himself in what form he would be reborn, because he pretended to believe or he pretended to believe in rebirths, he said it would be “as a park”, he would be reborn in the form of a park.[16] Some people want to be reborn as a blade of grass, and some people want to be reborn as a tree, that’s their business. But then, they can’t have the same synapses, can they? Because if we function through chemical synapses, then the tree-brain is finished. The most we can hope for is to witness, even encourage, the marriage of a bramble and a bindweed. And what could be more beautiful? So, either you prefer the strength of a poplar and you’ll be reborn as a poplar, which you already are, or you love the marriage of bindweed and bramble. The choice is yours! But in each case, you will think in a completely different way. Though there will still be opportunities to understand each other! Okay.

So, here are my provisional conclusions. Once again, we find ourselves faced with a completely different schema, a brain model where once again, the horizontal axis… the horizontal axis has become probabilistic and the vertical axis has become topological. From this point, it’s no longer a question of a mechanism of integration-differentiation. It’s a question of outside and inside. Through the relative distribution of the internal and external milieus. And in the other case, it’s no longer a question of sensory-motor linkages, so what will it be? It’s a question of probabilistic communication, and here we’re faced with a problem – before we have a short break – well, how does this kind of probabilistic communication come about and how can it be conceived? What is this mode of linkage that is no longer a sensory-motor type of linkage? That’s the point we’re at now. How about a little pause? Not for long, though. Make sure it’s no more than six minutes, alright? Six minutes… [Recording interrupted; 1:41:43]

… the formula, looking for a formula concerning a linkage that would no longer be of the sensory-motor type. So, you see, this is consistent with all that preceded, since all that preceded was based on a rupture, and on the existence of a sensory-motor rupture. So, in the case of a sensory-motor rupture, how can we conceive of linkages, and in what form? Unless, of course, there are no longer any linkages at all. But now I’d like to multiply the paths for research by suggesting four or five very different directions.

First direction: we see bizarre things going on in fields… for the moment, let’s call them “intermediate fields”. But between what are they intermediate? Between chance and determination, chance and dependence. And what do we mean by these terms? An example of chance: a lottery with successive chance draws, these draws being independent of one another. The very condition is that the draws are independent. The same applies to the game of roulette, where the throws are independent of one another. We can always derive… from such a field of chance we can always derive what we call laws of probability. But I’m mixing everything up. These so-called laws of probability are well known and subject to certain conditions: the independence of the particles or the throws, the fluidity of the surrounding space, the speed of diffusion and so on, and its connection – which we know well from the kinetic theory of gases – with the idea of Brownian motion, Brownian motion of particles in a fluid state. Then, on the other hand, we have determined linkages.

So, what is there in between? A whole field was identified, but it had yet to be recognized, under the name of a field of partially dependent aleatory phenomena, or semi-aleatory phenomena, partially dependent aleatory phenomena, that is, phenomena that don’t lead back… that lead back neither to the semi-aleatory phenomenon… mixtures of dependence and chance. First path: how can we obtain such a mix of the aleatory and the dependent? By operating through random draws, but successive random draws that depend on one another. Here we are in the domain of mathematics. What happens in the case of successive random draws that depend on one another? This is what we call “semi-aleatory phenomena”, aleatory phenomena that are partially dependent… [Recording interrupted; 1:47:02]

Part 3

… So, in a lottery, you make a draw, a first draw, A, a second draw, B, a third draw, C. Each of these draws is strictly independent of the others. So that, after a while, you have to change the person drawing so that there’s no muscular dependency on their part. Imagine the other situation. A strange chain… it will form a chain. A chain of random draws, but each random draw depending on the one before it. Such a chain… it has become well known in mathematics and in cybernetics under the name of one of its inventors: [Andrei] Markov, M-A-R-K-O two Fs or a single V – it’s up to you – a Markov chain. And to help you understand this, I’ll give you a quick example.

Markov began by studying an odd question: how would it be possible to create a fake Latin, or fake English, or fake French? How can you make a fake language? It’s well known as the “mumbo-jumbo problem”. How do you make mumbo-jumbo? You can always conceive… so you give yourself a series of urns there, urns or boxes. I suppose I give myself the following rule: each box will contain groups of three letters, the first two of which are constant… the first two of which are constant. So, in your first urn, you put a-b-a, a-b-b, a-b-c, a-b-d, a-b-e, a-b-f and so on. You see? In the second one, you put b-c-a, b-c-b, b-c-c, b-c-d, and so on. So each urn contains a group of… let’s call them “trigrams”, a group of three letters, the first two of which are constant. You follow me?

If you only do that, it won’t yet give you anything. But as you know, regarding languages, this method is capable of calculating the frequency, for example, in terms of letter groups. In French, we would say that the letter Q, in a maximum number of cases, is followed by U, and we’re able to calculate the frequency of the Q-U group in relation to groups including Q that would not be followed by U. Right now, the only one I can think of is COQ [rooster]. Similarly, in French, there’s a significant frequency of the letter H being preceded by C. You can calculate – and this, of course, is where computers are useful which is why all this was very much linked to computing problems, and Markov chains would never have been discovered before the advent of computers – you can establish the frequency of C-H. So, let’s say you make frequency calculations with a language, it’s been done a lot. You can also make frequency calculations regarding the language of a particular author. It’s been done for [James] Joyce, under very interesting conditions. You can make frequency calculations not just on groups of letters, but on words. This has been done for [Stéphane] Mallarmé, for example. It’s not clear where all this is leading… Yes, it will allow you to make mumbo-jumbo, fake Mallarmé, fake Joyce.

But how do you go about it? You take a frequency threshold which ensures that your trigram, that is your group of three letters, has a certain frequency in the language in question. Then you go ahead and draw from an urn, you take an urn, you take the urn… and each urn is defined by the first two letters of the trigrams. You take the letter, you start with the I-B letter… no, I mean with the I-B urn. In the example I have here, taken from a book by [Raymond] Ruyer, which I’ll tell you about… [Recording interrupted; 1:53:22]

… and then, in this case, we draw U. So we write IBU. The first draw gave you IBU. This is a lottery draw. IBU, I-B-U. Then you have two options: either you can take any urn and draw again, at which point it will be a succession of independent random draws; or – I hope you’ve already guessed – you can take the B-U urn and draw from that. Suppose you take out BUS. From the I-B urn, you’ve drawn IBU; from the BU urn, B-U, the last two letters, you’ve drawn BUS. Now you have to take the US box, U-S, from which you’ll take out U-S-C, okay? U-S-C. Then from the S-C box, you’ll take out S-C-E. Okay, so now you have a chain. Here you can obviously claim the right the right to cut it. This gives you, I’m reading slowly–I’m appealing particularly to those who have studied some Latin – IBUS, I-B-U-S, cut, you cut there; CENT, C-E-N-T, cut; you’re going to continue your draws, IPITIA, I-P-I-T-I-A, cut; VETIS, V-E-T-I-S, cut, and so on.

As we say, it looks unmistakably Latin, and you can see why, it’s not complicated, it would be amazing, since you’ve retained trigrams based on frequencies, on statistical frequencies carried out across the whole language. You can do the same with fake English, it’s what we’ll call gibberish. You’ve done Latin gibberish. In the same way, you can make Joyceian gibberish. Even this Latin gibberish, in this example, a particularly elaborate example developed by… in a book by a linguist called [Pierre] Guiraud, Les caractères statistiques du vocabulaire.[17] Well, you can make different kinds of gibberish. What is this all about? Why am I telling you all this? I’m telling you this because here we have a typical case that should help us understand what we mean by a “Markov chain’, better than if I defined it by mathematical formulas. You see how each draw is made at random, from the urn, but at the same time each draw depends on the previous draw, since for the second urn you have chosen the one determined by the last two letters of the trigram chosen in the first urn.

This is a clear example of what we will call semi-dependent aleatory phenomena, or partially dependent aleatory phenomena. Each time there is a random draw, but under conditions of dependence between the urns and the successive draws. Here we’re no longer in a lottery, nor in conditions of pure determinism. It’s semi-aleatory, a Markov chain. You could say that it’s literally a mixture, a structured mixture. We can say it’s a structured mixture in the sense that it’s not structured as a language, and yet nor is it a purely random mixture.

Second path for research, just to be quick. At first glance, this seems to be unrelated. In the field of cosmobiology, regarding the eternal problem of how… how a living organism comes into being, biologists have long been making – and also physicists and chemists – for a long time they have been making a very interesting hypothesis. Long before Markov chains, they too made use of a linguistic comparison. They said, if you give yourself a random bunch of letters from which you then draw, you have very little chance of coming up with a word. But if instead you give yourself syllables, you obviously have a much better chance of forming a word. And this gave them the idea of an “intermediate state”. In other words, they said, wouldn’t it be possible to conceive of the emergence of living things in the following way: through a passage through intermediate states, provided these states are stable, and we move from one intermediate state to another by means of fluctuations, by means of fluctuations around the mean of the previous state?

What does this mean in terms of cosmobiology? It means that, for example, we start with a particular state of body that we call “colloids”, which contain nothing of life, colloids, that would be the first state. Under certain conditions yet to be determined, there is a fluctuation, what we’ll call a fluctuation in relation to the mean state of the colloid. And this fluctuation gives what we call a “coacervate”, for example, a coacervate of compounds, carbon compounds. Now, fluctuations in relation to a mean state are a constant occurrence – I mention this right now because it’s essential – they occur constantly. Even in a gas, with a Brownian particle distribution, with random particle distribution, you always find fluctuations. What do we call a fluctuation? A moment when an unusual number of particles group together in a precise region. But these fluctuations are usually immediately neutralized or compensated for. This is what prevents the intermediate state from taking hold. As soon as it has formed, it has already dissipated.

So, the problem of cosmobiology will be: Can we imagine conditions where a fluctuation forms in relation to a given state, and the fluctuation no longer dissipates but is amplified in such a way as to give rise to a new state? This is a fundamental question. So let’s leave aside for the moment the problem of conditions, since we’ll be coming back to it. Under what conditions does a fluctuation, instead of being cancelled, become amplified? Let’s try to understand it better. We start with the colloidal state, fluctuating in relation to its mean state, which gives us a new state, a coacervate of carbon compounds, a set of carbon compounds. Once again, there’s every chance that the fluctuation will be cancelled. Let’s suppose that under certain conditions it isn’t cancelled. At that point, well, we will have intermediates, there will be new intermediates – I’m jumping ahead, to speed things up a bit – we’ll end up with the possibility of the formation of enzyme chains, or protein chains, protein chains that, however, won’t yet form a living organism.

But from intermediate state to intermediate state, in other words from amplified fluctuation to amplified fluctuation, can’t we conceive of the problem of the origin of life in another way, a new way? You see how this is very different from chance formation. So, what is it? What I’m describing to you is a Markov chain, but here it’s in terms of evolution, it’s a Markov chain. You have exactly one series of mutually dependent draws, a series of mutually dependent random draws, where each time the fluctuation marks a chance which, providing it isn’t cancelled out, if conditions are such that they permit amplification, will lead to a new draw which will once again produce another… you have a sequence of draws that depend on one another, even though each individual draw is random. You have a Markov chain. Or some kind of Markov chain. For the moment, we’ll keep… here, everything I’m saying will be worthless if we forget our problem: that’s all very well, but for a fluctuation to generate a new state, which will be in semi-aleatory relation, you see, it will be precisely in an aleatory relation that is partially dependent on the previous state. The coacervate of carbonaceous compounds will be in semi-aleatory, semi-dependent relation with the colloidal state, provided that – again, I haven’t really answered the question yet – the fluctuation isn’t cancelled out.

There’s a text by [Charles] Darwin, a letter by Darwin, which I think is brilliant, where Darwin as a young, actually not so young, man recounts how he is constantly being asked: If life had simply begun, then why couldn’t it begin again today? It was the anti-evolutionists of Darwin’s time who were already resorting to this argument: If it happened once, why shouldn’t it happen again? And Darwin replied how it would be very difficult today for another form of life to emerge. And why is that? Suppose that in a small pond – this text is brilliant, because it gives us the answer – suppose that in a small pond – obviously the same thing wouldn’t happen in the open sea – suppose that in a small pond, coacervates form from colloidal states. Well, today, they would have no chance of producing an amplifying fluctuation. Why not? Because they’d immediately be eaten, they’d immediately be eaten by the living creatures that were already there. They would be immediately absorbed, there would always be a fish to swallow them. So there’s a simple reason why life has only been able to form once: once it is produced, it consumes everything. So, there’s not much chance of another life form with chains of a different type emerging. The chains of a different type would immediately be swallowed up. But his remark, “in a small pond”, should once again enchant us, because it sets us on the path towards the solution. Under what conditions can a fluctuation become amplifying? But this is just a path. We don’t know yet, we simply don’t know yet.

So that would be the second research path: cosmobiology. Now I conclude this point here, once again, because I aim to go very slowly. You can see that this linkage of intermediate stable states, where we go from one to the other by means of amplified or amplifying fluctuations, form a Markov chain, or a kind of Markov chain, in other words a sequence of partially dependent aleatory phenomena.

The third type of research is that undertaken by [Ilya] Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers. This research focuses precisely on fluctuations – it’s in chapter 6 of La nouvelle alliance[18] – where they directly pose the question: Under what conditions does a fluctuation become amplifying, and under what conditions, on the contrary, is it cancelled or balanced out? So, here they should be able to give us an answer to the question we posed earlier. The state, the primary state where fluctuations are immediately balanced out is once again the state of the kinetic theory of gases. A large number of particles distributed in a fluid medium, fluid – ultimately, we could say ideally fluid – a large number of particles in an ideally fluid medium, what happens to their motion? Each particle follows what we can call free motion. What is free motion? It’s the average distance travelled by a particle before another particle collides with it.

You see why I insist on this free motion. Why do we need the fluid medium of a gas? Because in a solid, particles are no longer independent. Why are particles no longer independent in a solid, or even in a liquid? Because the actual state of the solid or liquid brings them together in a region where they lose their very independence, they are caught in the region of the solid in such a way that they can no longer follow free motion, they lose their free motion. In a gas, with Brownian motion of the particles… You see, Brownian motion is therefore when a particle follows a trajectory until it is, until it collides with another particle that sends it off in another direction and so on. And you have the type of random distribution subject to the laws of probability insofar as you have a very large number of particles. A fluctuation occurs when a large or at least a significant proportion of this large number of particles find themselves in the same region.

I would say that here it’s immediately corrected, it’s cancelled out. Why? Because, Prigogine and Stengers tell us, because of the effect of diffusion. Indeed, in a fluid medium, it’s because of the diffusion that binds all the regions of the system. It’s because of the diffusion that binds all the regions of the system with the environment, in particular the fluctuating region, which is to say the region where the abnormal concentration of particles has appeared. And it’s because there’s such a high level of diffusion between the region where the fluctuation takes place and the environment that the fluctuation is immediately balanced out and the probabilistic distribution of particles re-established. So, it’s a question of diffusion.

So, the answer to my question is that a threshold has to be crossed for a fluctuation not to be cancelled or balanced out but to be amplified. What would it take for a fluctuation to be amplified to the point of generating a new state? The fluctuating region would have to be somehow protected from the rapid diffusion that re-establishes the mean state. Prigogine goes even further, because he says: You know, this applies to our societies too. How can we explain the fact that our societies, which are very complex, are so stable, when at every moment there are fluctuations, that is, deviations from the mean? Well, he says, there’s an equivalent to what happens in fluidity: it’s the speed of information. That’s why the speed of information is fundamentally something… it’s linked to maintaining order. It’s the speed of information that immediately cancels out the fluctuations and returns them to…. that crushes them.