December 10, 1985

“Historical formation” leaves us with the idea that one era precedes what occurs in the era, whereas, for Foucault, this is just the reverse: an historical formation unfolds from a particular mode of interveaving of the visible and the sayable. That is, an historical formation unfolds from a way in which light falls, a way in which “there is language”, and from a way in which the statements of language and visibilities of light interweave.

Seminar Introduction

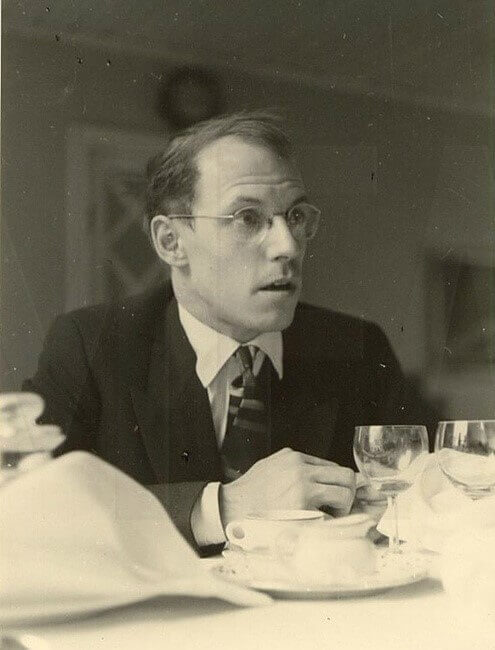

After Michel Foucault’s death from AIDS on June 25, 1984, Deleuze decided to devote an entire year of his seminar to a study of Foucault’s writings. Deleuze analyses in detail what he took to be the three “axes” of Foucault’s thought: knowledge, power, and subjectivation. Parts of the seminar contributed to the publication of Deleuze’s book Foucault (Paris: Minuit, 1986), which subsequently appeared in an English translation by Seán Hand (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

For archival purposes, the English translations are based on the original transcripts from Paris 8, all of which have been revised with reference to the BNF recordings available thanks to Hidenobu Suzuki, and with the generous assistance of Marc Haas.

English Translation

First reminding participants that discussion still focuses on the two irreducible forms (the form of the visible and the form of the statable), Deleuze presents Foucault’s admiration for Raymond Roussel’s work which, for Foucault, reveals a veritable battle between the visible and the statable. Deleuze indicates how, for the statable and the visible, there exists the condition (the “there is” of language, and light of the visible) and the conditioned (le conditionné) (the statement itself, and scintillation), and Foucault emphasizes the gap between the “there is” of language and the statements disseminated in language, into which the visible can seep. After the Foucault-Roussel examination, Deleuze reaches some conclusions: the first axis of Foucault’s thought is “knowledge” (savoir), with two parts for which Deleuze examines two kinds of dualism, from Descartes to Kant, through Spinoza and Bergson. A third kind interests Foucault, the one inscribed in speech, a preparatory stage of multiplicity and pure pluralism. Deleuze indicates some bases of multiplicity in mathematics, then emphasizing that the parts of knowledge are interwoven in the strata of historical formations. Hence, Deleuze suggests that the reconciliation of mutual captures of the forms can occur only in the dimension constituted by relations of power, requiring that he explain why power is the second axis. He concludes that even if power is silent and blind, it nonetheless constructs seeing and speaking, and Deleuze explores how we are made to speak through power, that is, “spotlighting” as an operation of power. Given Foucault’s interest in “lives of infamous men”, Deleuze provides three definitions of “infamy”: classical (e.g., Gilles de Rais), baroque (cf. Borges), and modern (e.g. power “spotlighting” the individual). With the “spotlight” on the “ordinary man” (cf. Foucault’s example in lettres de cachet), Deleuze concludes by outlining the three requirements between power and knowledge, particularly the primacy of power over knowledge.

Download

Gilles Deleuze

Seminar on Foucault, 1985-1986

Part I: Knowledge (Historical Formations)

Lecture 07, 10 December 1985

Transcribed by Annabelle Dufourcq; time stamp and additional revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Translated by Samantha Bankston; additional revisions, Charles J. Stivale

Part 1

… So that’s where we are now. Ultimately…we aren’t moving on, but we are advancing within the same problem, and it is by dint of advancing within this problem or pushing this problem forward that we will get to the end. This problem is this: that we are still faced with two irreducible forms: the form of the visible, the form of the statable. There isn’t an isomorphic nature to these forms. In other words, there is neither a form common to the visible and the statable, nor a correspondence between the two forms. So, there is neither conformity – a common form – nor a one-to-one correspondence from one form to the other. There is a difference in nature or, according to [Maurice] Blanchot’s terminology, there is a “non-relation”, a non-relation between the visible and the statable, thus, a disjunction, a gap. This is the disjunction of light (as the form of the visible) / language (as the form of the statable).[1]

We immediately notice – and I emphasize this point because we will need to come back to it later – that one of the immediate consequences of such a point of view is a fundamental criticism of intentionality. [Pause] Or, if you prefer, it is a critique of phenomenology, at least in its vulgar form. By “vulgar”, I mean nothing pejorative, I mean: what has been retained as the most known, what has been retained as the most prevalent understanding of phenomenology is the idea of intentionality, not only of consciousness, but of syntheses of consciousness according to the famous formulation that “all consciousness is the consciousness of something.” And, from this point of view, language, one synthesis of consciousness among others, is presented as being intentional, exhibiting an intentionality towards a state of affairs, or of something. It’s as if language is aiming toward something.

We have seen how Foucault so violently opposes and rejects this intentional relation in a very simple sense: if we understand what a statement is, we see that the object of the statement is an intrinsic variable of the statement itself. So, the statement does have an object, but it has nothing to do with the visible object and nothing to do with a state of affairs. The object of the statement is an intrinsic variable or a derivative of the statement itself. It is therefore impossible for the statement to intend toward an object that is external to it. Thus, the true statement that corresponds to the visible pipe is, once again, “this is not a pipe” and not “this is a pipe,” or, to use a serious version of the same idea, the true statement that corresponds to the visible form of the “prison” is not “this is a prison”; it is “this is not a prison,” insofar as criminal law statements do not pertain to the prison.

It would therefore be easy to conclude – I’m saying this parenthetically to prepare you for an eventual discussion—that this is where Foucault’s rupture with phenomenology takes place, and we are well aware that other factors must be taken into account, that phenomenology, in its very development, in the late [Edmund] Husserl, as in [Martin] Heidegger, and in the late [Maurice] Merleau-Ponty, didn’t stop running up against the need to overcome intentionality itself, and why? It is because the history of intentionality, which we will discover again, this idea of intending, or the idea of consciousness as the consciousness of something … [Pause; interruption of the session due to an abrupt sound of a loudspeaker or a recording]

Well…, this history of intentionality was very curious because, you see, it was created to fully break with psychologism and naturalism. I’m saying this all very quickly for those who know… And intentionality typically fell back into another psychology, another naturalism. In particular, it was very difficult, and it was becoming more and more difficult given the progress of the…given the evolution of psychology, to distinguish intentionality from learning. We’ll see all of that in greater detail. Thus, the phenomenologists found themselves [Deleuze laughs] in a very strange situation because, they finally ended up having to break with intentionality. So, we can’t say to ourselves: well, here we are, Foucault breaks with phenomenology because phenomenology ends up having to break with it also. So, we will see that the Foucault/phenomenology relations are much more complicated… [Deleuze does not complete the sentence]

But for the moment we’re not there yet. We’re simply noting that there is a rupture of intentionality in favor of a kind of dualism, of difference in nature between two forms, the visible and the statable; we cannot say that the statement refers to a thing or a state of affairs. So we are in the midst of the non-relation of the visible and the statable, and yet we always fall back on the same scream… it becomes a scream, an emergency call, and yet: there must be a relation… There must be a relation between the visible prison and the statement “this is not a prison,” there must be a relationship between [René] Magritte’s visible pipe and Magritte’s statement “this is not a pipe.” Why do they have to be related? Because, as we know, the form of the visible and the form of the statable make up knowledge… If they make up knowledge, the foundation of the non-relation between the two parts of knowledge must create or cause a relation to surface. There’s no other option. And this is what I was saying: well, it’s very weird, how are we going to explain that?

Let’s reformulate the question: why does Foucault feel so much pleasure, so much amusement, and, at the same time, so much admiration when discovering and reading Raymond Roussel? The answer is simple in that in addition to the pleasure and joy that he gets from this poet, he finds sketches toward a solution to this problem, sketches of a very curious kind of solution because, in a sense, they are exemplary solutions.[2] What would we consider an exemplary solution? An exemplary solution is a solution that emerges under artificial conditions. It is therefore all the purer as it arises in relation to perfectly artificial conditions, even if it means that it can then be extended into common conditions. And, finally, perhaps there are many problems that arise in this way, at the level of artificial conditions. And, indeed, it is by employing a completely bizarre language procedure—a procedure of the statement and a procedure of visibility—that Roussel develops poems that seem to provide us with one or even several solutions to this problem. Hence, [Pause] I am trying to, I am trying to understand Foucault’s book on Roussel in accordance with Roussel’s own terms. Close the door, please… [Interruption of the recording] [10:25]

… So, the fact that Roussel’s procedures are poetic procedures that Roussel constructed himself is one thing, but you need to pay attention to two things at the same time: Roussel’s completely artificial procedure, as well as the possibilities that this procedure gives us, the indication… [Interruption of the recording] [10:50]

… The first path that Foucault takes from Roussel is very simple and we have already tried to address it. It consists in saying: all right, the two forms, the form of the visible and the form of the statable, differ in nature, but that does not prevent them from mutually presupposing one another. That is, one presupposes the other and the other presupposes the other. In concrete terms this means that from one form to another, from the visible to the statable and from the statable to the visible, there are always mutual captures. “Capture” is not a word Foucault uses. I’m using it for convenience, uh, “mutual captures.” But, on the other hand, all the words that Foucault uses are polemical terms of violence. And you can actually see why. If the two forms are really heterogeneous and irreducible to one other, it seems like there’s a war between the two and that the primary relationship between the two can only be that of a war, of violence. One will take something from the other. The other one will then take something from that one, and it will be by tearing it off, by capturing it, by taking it. These will be strangleholds. They will be the strangleholds of fighters.

And already in This Is Not a Pipe, this theme of mutual presupposition conceived as a mutual capture of the visible and the statable is constantly presented by Foucault as a real struggle. I’m quoting page 33 from This Is Not a Pipe: “Between the face and the text…”, i.e., the visible and the statable, “between the face and the text, from one to the other, attacks are launched,” attacks are launched, “arrows shot against the opposing target, activities of undermining and destruction, spears and wounds, a battle.” All right. It’s a battle.

We need to remember this passage so we will be less surprised when Foucault feels the need to go beyond the axis of knowledge towards the axis of power where the battle is uniquely explained. These are already passages concerning knowledge, i.e. the two elements of knowledge, the visible and the statable, and you must sense that they are entirely oriented towards the discovery of power as the real stake of the battle. Page 48: “In this broken and drifting space,” where the visible and the statable meet, “In this broken and drifting space, strange relationships are formed, intrusions occur, abrupt destructive invasions, avalanches of images in the middle of words,” avalanches of visibility in the middle of statements, “verbal flashes that crisscross drawings and shatter them.” Here too, there is an affirmation of struggle, of a stranglehold, and battle…. [Interruption of the recording] [14:58][3]

Part 2

… What can, what can, what can be torn off? We have no idea. All right, let’s see. Can Roussel help us? Roussel wrote a famous book, and Roussel was a poet at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, which was obviously…, which seemed strange…, you have to love it. Foucault loved it very much. The Nouveau Roman really liked Roussel, and [Alain] Robbe-Grillet wrote a very important article about Roussel. There is probably something to see here, and this is not the first time I’ve tried to establish an affinity between Foucault and the Nouveau Roman. In any case, what was so fascinating, or what is so fascinating about Roussel’s work?

Fortunately, Roussel left us a book entitled How I Wrote Certain of My Books.[4] How I wrote some of my books, not all of them, huh? Some of them. So, let’s proceed confidently: how did Roussel write some of his books? He tells us in the following way: suppose, I tell you about a strange poetic… venture, a strange poetic venture. Imagine the war cry: I’ll split words, I’ll split sentences! I’ll split sentences. This is of interest to us, since you will recall that in all our previous analyses, we’ve seen that the discovery of Foucault’s statement implied that words, sentences and propositions are split. If we could not split words, sentences and propositions, we would never discover statements. Now is the time to ask yourself: what does it mean to split words, sentences and propositions? It means constructing two sentences whose difference is infinitely small. That’s it: open the sentence, split the sentence. Construct two sentences whose difference is infinitely small. [Pause]

Roussel gives an example that animates one of his great works.[5] Here is a sentence or at least a fragment of a sentence: “The white letters on the cushions of the old billiard table (”les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux billard”) You see, in this sentence, “letters (lettres)” means “signs (signes)”, “of white (du blanc)”, “white (blanc)” means the small cube that is always present on the pool table, “on the cushions (sur les bandes)”, “cushions (bandes)” means “billiard table edges”, “billiard (billard)” means billiard. “The white letters on the cushions of the old billiard table.” Consider sentence 2: “The white letters on the hordes of the old plunderer (Les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux pillard).” This time, we can assume that “letters (lettres)” means “missives”, “white (blanc)” means “a white man”, “hordes (bandes)” means “hordes”, “plunderer (pillard)” means plunderer, and the fact that it refers to a white person implies that the looter is a black person. “The white man’s letters on the hordes of the old plunderer.” I have my two sentences that are distinguished by what? What Foucault would call “a small snag.” What’s the snag? Or the small difference. The little snag is: b/p. B for “billiard (billard)” versus P for “plunderer (pillard).” Otherwise the words are the same. “Les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux b/pillard.”

There you go. So, b/p: you will admire that this is exactly what linguistics – Roussel having not expected it – calls “a phoneme relationship.” It’s the little snag: “Did you say b or did you say p? You said b and, if you pronounce the b’s like p’s, what did you say? Did you say, “the white letters on the cushions of the old pool table” or “the old plunderer”? Think about how this procedure inspired so many great authors; you constantly find it in Lewis Carroll. In all respects, we can say that paradoxical language procedures are often of this type, and I am not saying that this is the only one possible. Well, I have my two sentences. I opened the sentence. That’s what it means to split the sentence, open the sentence. Why am I releasing the statement from it? Well, the statement is exactly this — if you have understood everything we did with the statement — in this artificial construction of the statement, I could ask what it is. It’s “les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux (The white letters on the cushions of the old billiard table/ The white letters on the hordes of the old plunderer)” and then I write… [Deleuze looks for a piece of chalk to write on the board]

A student: We can’t see anything at all.

Deleuze: Well, you’ll add to this on your own — thank you, I need it that way — So, I write “les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux (The white letters on the cushions of the old billiard table/ The white letters on the hordes of the old plunderer),” and then I put… [Pause] Here, I extracted a statement from the sentences. You can tell me: don’t fuck with the world! Well, let’s say it’s a humorous version of something serious, if you take it that way, but we can prefer the humorous version. If someone asked me: what is a statement and how does it differ from sentences? I would say: the sentences are one or the other. They are “the white letters on the hordes of the old plunderer” or “the old billiards”. They’re one or the other. The statement is: “Les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux b/p illard [b over p – illard].” Why is that the statement? We already saw why. To be serious, it is because these are completely artificial conditions, but in the natural conditions of language we saw that the statement was defined by immanent variation, by moving from one homogeneous system to another homogeneous system, the perpetual passage from one system to another. So, if I provide artificial conditions to make this clear, you need to remember everything we’ve done thus far, which was done under more serious, if less striking, conditions. But we are happy to demonstrate what we tried to show in a more serious manner previously.

So, all right, I’ve identified that: the statement. By splitting a sentence, or splitting sentences, I identified the statement. But I couldn’t clarify the statement of sentences without providing a number of visible scenarios. Where will visibility appear? As soon as I try to get one of the sentences to connect to the other. At that precise moment, I have to paint strange visible scenarios, however unlikely they may be; I have to create paradoxical visibilities to ensure the junction of the two sentences. For example, “The old plunderer”, who is King Talou in Roussel’s story, the old plunderer will have to be bound and wear a kind of fancy dress, a dress with a train. You can see that: Talou’s dress with a train. Why does he need to have a dress with a train, or why does a dress with a train have to appear in the story? Because a dress train (traine) is a tail (queue). And that “queue” is “a billiard cue (queue)”… right? And this all goes on to infinity. In each case, proliferations will have to give rise to visible proliferations that keep reconnecting Sentence 2 to Sentence 1.

Good, and just like that, Roussel constructs his whole poem where the gap between the two sentences, the gap that gives rise to the statement, cannot close without creating visibilities as well, that is, unusual spectacles like Talou’s dress with a train/tail. Well, I could elaborate this even further, but those who are interested should read How I Wrote Certain of My Books, if they haven’t done so already, or read Roussel’s great book related to this subject called Impressions of Africa.

I’ll summarize: by opening sentences, I reveal a statement, but at the same time I create and proliferate a whole series of visual images, by which sentence 2 reconnects to sentence 1. This is a typical phenomenon of capture. I opened the sentences like a jaw, and they shut on visibilities. This is exactly what we mean by capture. This is how the statement captures the visible. Sentence 2 can only reconnect to the statement through these violently visual and visualized scenarios.

However, Foucault notes that the title How I Wrote Certain of My Books excludes certain other books. And, indeed, there are books that… Oh no, I’m going to use another example because it is… uh… it is extremely pertinent. There is a poem by Roussel, which is very beautiful, well… uh… and very funny, called “Chiquenaude”, “Chiquenaude”. What is the split sentence this time? It’s: “the understudy’s lines in Forban’s play… (les vers de la doublure dans la pièce de Forban)…” You see a bandit (forban), but “Forban” is used here as a proper name, it’s the character, it’s a character named Forban. “The understudy’s lines in Forban’s play Red Heel (les vers de la doublure dans la pièce de Forban Talon rouge)”, “heel (talon)”: a shoe heel, “red heel (talon rouge)”. There, you see. It’s a fragment of a sentence. I can say: “I heard understudy’s lines in the play Forban Red Heel“, what does that mean? The verses: well, they form a poetic unit. The understudy: it’s because I was there one night when the actor’s understudy replaced the actor. The understudy’s lines in the play, in the play called “Forban Red Heel“. It’s allegedly the name of a play. I’m constructing my sentence with a little snag. Now the snag will… uh, justify itself all the more. And I’ll say: “The understudy’s lines in the play”… until then it’s the same,”…in the play of strong (…dans la pièce fort…)” in the sense of powerful,”… strong red pants (fort pantalon rouge)”. “The moth holes in the lining of the strong red pants.” I opened up the sentence [Deleuze laughs], I opened up the sentences. I formed a jaw system, a double jaw system.

This time, the second sentence is about moths, the animal, the animal that eats our fabric. The lining, well, that’s extra material sewn into a suit. So that means literally, if you will, a shabby lining. The lining (la doublure) this time is no longer a theatre play (pièce), it’s an extra piece of sewing material. “…. of red pants.” There you go. How will sentence 2 reconnect to sentence 1? So, I have a new statement. The statement carries the immanent variation, straddling both system; it is b over p. [Pause] How will 2 rejoin 1? Well, suppose that, in the play, Forban Red Heel, there is a fairy who puts a shabby lining in the devil’s or the bandit’s pants. This shabby lining will therefore be called upon to tear apart and, in so doing, ruin the bandit’s endeavors. There you go. Sentence 2 rejoins sentence 1 since “the moth holes in the lining of the strong red pants” takes place in “the understudy’s lines in the play Forban Red Heel“. Good. If we hadn’t seen the serious version of all this, it wouldn’t make any sense. Once you have seen the serious version, you understand that, from then on, as soon as he has stated it, the statement does not split the sentences without creating visibilities through which one of the sentences rejoins the other.

Now, I was saying — back to the other aspect — good, but there are works that lack a procedure in Roussel. What are the works that lack a procedure? I think that it speaks to Foucault’s talent that his analysis of Roussel ultimately shows how the works that lack a procedure, where Roussel does not provide a key, are the inverse of the works that use a procedure. The works that lack a procedure are very, very curious in Roussel; they consist of endless descriptions. But descriptions of what? That’s why… that’s the aspect of Roussel’s work that struck the Nouveau Roman so much. Endless descriptions of what? Well, endless descriptions of what is endlessly describable by its very nature. And what is that? Strangely, what is described endlessly by its very nature are not visual things, but images and, preferably small images of a certain kind: vignettes. That’s the infinity of sight. It’s what you can only see with a magnifying glass.

Why? What is that supposed to mean? We’ll see in a moment. But in his visual non-linguistic works—of course they are descriptions in language, but they are descriptive works—in Roussel’s purely descriptive works, characterized specifically by “sight”, what is happening? Roussel spends hundreds and hundreds and hundreds and thousands of verses describing what you see in the lens of a penholder. I don’t know if they still exist, you know, but in the past they did; they were really beautiful, they must still exist in Montmartre… if you want to understand, go to Montmartre and buy a penholder… You… There is a small magnifying glass, a lens, in the… I don’t know what, there in the thing… in the handle… in the handle, you put your eye up to it and you see… and you see…it’s probably very simple these days, these days you see the Eiffel Tower and that’s it… But no, in Roussel’s time, it wasn’t like that, you saw something truly inexhaustible, a scene of eighty people… the smaller it is the more elaborate it is. There you go. The lens penholder. Another example that Roussel describes in hundreds of verses: a label of Evian water.

A third example: the letterhead from a hotel, a luxury hotel. Especially in the cities with water, amazing, huge letterhead where there is a very large hotel, and then portrayed very, very small are people taking water at the spa, and there are perhaps a hundred people taking water. This makes Roussel happy and he creates huge books, he’s happy describing: what you see in the lens of a penholder, on the label of a water bottle, or on letterhead. Think, what does that mean? Well, this time it’s the other way around. Foucault is absolutely right to say: but the works without a procedure, the works of visual description, are the opposite of the linguistic procedure. Why? You know, sometimes we see this in the movies and each of us dreams of knowing how to do it… people who swipe a card in a door and they manage to open a door, just like that. Police officers and bandits do it all the time. A small, hard card and then they literally split the door open.

Roussel’s idea is that if you slip a small vignette into something, the thing will open up. It’s a very curious idea, a crazy idea. But we can always try. You slip your little vignette between two things… and then… bang, it’s like a click, things open up. In other words, we find the exact same theme that we discovered through what seemed to me to be serious analyses: [Pause] to understand what visibility is, we have to split things up. Moreover, it is visibility that splits things up. And, in the same way, just as there is a fundamental relationship between stating and splitting sentences, there is a fundamental relationship between visibility and splitting things.

Why? Because, under conditions of the lens, the vignette, the miniature, everything you see, the gestures of the little characters, gives rise to endless statements. And this is how Roussel actually describes a character in the… uh…. on the small illustration of the Evian water bottle: “A tall woman, with a cautious coldness in her approach has a strong impression of herself and is never intimidated…” You notice that they are poems, they rhyme. “She thinks she knows almost everything; she is a bluestocking and ignores people who don’t read much; she decides when we talk about literature. Her letters, without a flat word, without any deletions, only emerge after laborious drafts.” You can see that the miniaturized gesture captured on the small illustration evokes all kinds of statements based on the woman’s attitude, yeah. According to her attitude, she is a confident woman, she has a strong impression of herself and is never intimidated, she thinks she knows almost everything, she is a bluestocking and, as a result there’s a whole flowering of statements. “… And ignores people who don’t read much”: there it takes off, until then he described the miniature image. “… And ignores people who don’t read much,” so from there, there are statements about the woman and statements from the woman herself. “She decides when we talk about literature.” In a typical fashion we hear the statement about the woman. “Her letters, without a flat word, without any deletions”, this is the typical domain of statements. You notice that I’m going quickly because we’ve spent a long time on this.

What’s going on? It’s because, as I was saying: to extract the statement you have to split things up… you have to… you have to split sentences. But when you have split the sentences, extracting the statement, you inevitably create a whole bloom of visibilities. Conversely: you split things to extract visibilities, flat visibilities, miniature visibilities, the planarity of the visible. In fact, we saw that what was visible was not the thing. Now, this planarity of the visible, you only release it by causing a proliferation of a multitude of statements. So that’s what mutual captures are all about. From the visible to the statable, from the statable to the visible, all kinds of captures will occur. And why in one way? Well, let’s go back to being serious. What did our previous schemas show? The form of the statable is twofold, as we have seen, why? Well, the form of the statable includes a condition and a conditioned. The condition is “there is language”, it’s the “there is” of language, the conditioned is the statement.

The form of the visible is twofold: [Pause] the condition is the light, the conditioned is the reflection, brightness, scintillation. [Pause] And here it is. This is what interests me. It was achieved in our previous analyses. I mean, that’s where we rediscover our serious analysis. There is something very disturbing, which is: what relation do the conditioned and the condition form in each case? Through what kind of relation? Well, it’s always, always and at all levels the same thing that comes up in Foucault. It is a relation of exteriority. It is a relation of exteriority. What does that mean? That means that the condition imposes a regime of dispersion on the conditioned, a regime of dissemination. Language is the condition of statements, but statements only exist while disseminated in language. Language is a form of exteriority with respect to statements. The same goes for the visible. It is true that light is the condition, but as a condition, it is the form in which flashes and scintillations are dispersed and disseminated. Light is the form of exteriority for reflections, flashes, and scintillations. [Pause]

Thus, in this respect, Foucault breaks away from Kant, because there is no form of interiority; any form is a form of exteriority. Let me digress, because this poses a problem. It might help us avoid poor readings of Foucault, even at an involuntary level. Uh… on their first reading, many people get the impression that Foucault is first and foremost a great thinker of confinement. And two of his main books are always invoked: one on the hospital, the asylum in the 17th century, [Pause] and the other on the prison. This impression can even apply to incredibly talented and impressive authors. For example, I am thinking of the way that Paul Virilio has criticized Foucault on several occasions. So, it doesn’t matter as long as it’s Virilio, because Virilio has his own original thought, and, in that sense, at that moment, his problem is not to understand Foucault, but if our problem is to understand Foucault, then we can’t just follow the trajectory of Virilio’s objection. Virilio said to Foucault: “But you are obsessed with confinement. And from the point of view of the worst forms of social repression, confinement is a very small thing. There is something much more important than confinement, it is the grid and the grid in open space, the open-air grid.” And when Virilio tries to summarize his critique of Foucault, he says: well, the police are not the prison, the police — as he says very well – are the roadways, the police are the roadways, that is, the control of the streets, the control of free spaces and not the spaces of enclosure.

In other words, what is dangerous is where the police act, which is at the periphery, not the dead end. It is a matter of creating a grid on free spaces, rather than constituting spaces of enclosure. So, at first glance, one might have the impression that this objection is valid. In fact, I think what Virilio says is what Foucault said all along. Undoubtedly, he said it in a different style, with a different tone…I mean, none of that is important. And that doesn’t take anything away from Virilio’s inventiveness in other respects, since, again, Virilio’s task isn’t to try to understand Foucault. But it seems obvious to me that if we pay too much attention to the theme of confinement in Foucault’s thought, which is an existent theme, and we will soon see in what sense, then we risk not understanding anything at all about the entirety of his thought. Why? Because it is extremely obvious that confinement is not a function for Foucault. And it was never a function for Foucault. Locking up is not a social function. It is an ambiguous means by which very diverse functions are carried out.

What do I mean? Something very simple. The asylum in the 17th century and the prison in the 18th-19th centuries are places of confinement. Okay, they are places of confinement, and yet they do not serve the same social function at all. When the asylum locks people up in the 17th century, and locks up madmen, vagrants, the unemployed, etc., this locking up supports which function? An exile. It’s about removing people from society. This is the “exile” function that was carried out in the 17th century in the general hospital. However, you will notice that exile is a function of exteriority, it’s about putting people outside of society. So, the world of confinement usually serves an external function: exile. They only lock up in order to exile. In the 19th century, regarding prison… you will tell me: it too is a form of exile… yes, in a way it’s a removal from society, but it is a matter of survival. The “exile”, the “inner exile” aspect of prison is about survival. In fact, it has a new function. This is because, in the space of confinement in prison, there is a very strict grid pattern. It’s a grid of daily life, from the most miniscule moments of quotidian life, the control of everyday life, the control of everydayness. This is much more important than exile, it is a function other than exile.

The prison is a place of the grid pattern. In some very brilliant passages, this allows Foucault to say: asylum is the heir to the plague… no, excuse me, the asylum is the heir to leprosy, prison is the heir to the plague. What does he mean in these beautiful passages from Discipline and Punish? He means: the leper was the perfect and pure image of exile, cut off from society. The leper colony was a function of “exile”. That’s not at all what the plague is. The plague is something else. When the plague breaks out in the city, what happens? The plague is how this kind of control emerges, the control of the everyday life. Every morning officials pass by, and they must be told about the health of each house’s inhabitants. The rules for exposing corpses and visiting patients are codified down to the smallest detail. According to Foucault, the plagued village is what established the grid of cities. This is a “grid” function and no longer an “exile” function. We don’t hunt down people who have the plague. Furthermore, not only is this impossible, but hunting them down would be extremely dangerous. And, when a house is afflicted with a new case of the plague, the house must declare it immediately; it is with the plague that our modern regime of everyday control emerges.

So, in this respect, Foucault can say: the prison will take over from the plague, just like the general asylum… just as the general hospital took over from leprosy. But you see that with these two spaces of confinement…we would be wrong to believe that “confinement” explains their nature…that’s not at all the case. “Locking up” is a massive generality that doesn’t tell us anything. Foucault was never the thinker of confinement for the very simple reason that, for him, any form is a form of exteriority. The function that the space of “asylum” confinement serves is the “exile” function of exteriority. The function that the prison serves is the function of exteriority, a “grid in an open space.” And that is why criminal law, at the time of imprisonment, and criminal law in the 18th and 19th centuries is by no means centered on prison. Why? Because it imagines a much more subtle and much more advanced grid pattern. This is what Discipline and Punish tries to show: since criminal lawyers, criminal law, and jurists imagine a grid system that is coextensive with the city, the prison does not really interest them.

And when the prison asserts itself by virtue of its own origin, which is not of legal origin, which is of disciplinary origin, as we have seen, when the prison asserts itself, it is because it says… if I were to speak for the prison, I would say: “I prison…” The speech that the prison would give to lawyers and jurists, in its own defense, would be the following: “I, as a prison, am better able than anyone to fulfill the wishes of you criminal lawyers, as the great grid, that is, the control of everyday life.” Simply put, the prison would add, “I can only do it with my modest means, in a closed environment. The time has not yet come to put a grid on open space, we do not know how to do it.” But, as soon as we know how to do it, the prison will lose its usefulness. What matters is not “confinement”, but the very diverse functions of exteriority that confinement serves. And you can see why Foucault, perpetually… and Foucault would be the first to say: well obviously, what counted—in this respect his agreement with Virilio would be very profound, since there was only a misunderstanding between the two—what counts is the grid; the simple fact is that, historically, the grid first had to be tested under the artificial conditions of the prison.

But even spaces of confinement, and you’ll see that spaces of confinement are transitional stages, are variables of a function of exteriority. Strictly speaking, they are variables of a function of exteriority, and functions of exteriority can do without these variables. Exile can function without a space of confinement and that is how madmen were treated in the Renaissance. In the Renaissance, we used to put them on a boat, leave and then off you go! They were exiled without being locked up. As Foucault says in a very beautiful formulation, if they were in fact locked up on a boat, they were prisoners on the outside. They were prisoners on the outside: they were exiled as a function of exteriority. So: exile or grid? That is the fundamental choice, but they are two functions of exteriority. In short, spaces of confinement are secondary variables in relation to social functions, which are always functions of exteriority. What am I getting at with all this? … [Interruption of the recording] [1:01:43]

Part 3

…which has never been enough for him, which is like a kind of artificial experiment to make us understand something else. It is clear that social function are not only functions of exteriority, but every form is a form of exteriority. Why? Because a form is a condition. The form of the visible is the condition of visibilities. The form of language is the condition of statements. Now the conditioned is in a particular relationship with the condition that the conditioned only exists as dispersed in the… uh under the condition, not “in” the condition: I would be reintroducing an interiority. The condition positions the conditioned as dispersed, disseminated. [Pause] And maybe that’s the only way to understand it.

I’m coming back to Roussel’s stories from two sides: the opening of things that will lead to statements, the opening of sentences that will lead to visibility. At first sight, one might think that these mutual captures, if you followed what I said earlier…this exercise of force is purely verbal because: how are mutual captures possible if the two forms are completely foreign to one another? It’s very nice to say: there are mutual captures, but how is that possible if the form of the visible and the form of the statable… How can there be a mutual capture when the forms cannot mix together? That’s precisely the problem. How can there be a mutual capture if the forms cannot mix together? Listen to the possible answer.

It’s not a question of the forms mixing, as each of the two forms introduces a condition and a conditioned. That being said, the condition does not contain the conditioned. The conditioned is dispersed under the condition. In other words, it is between…between the conditioned and the condition of one form that something can slide into the other form. Perhaps while I’m saying this, we’re saying to ourselves: this isn’t enough. Maybe it’s one way, maybe it’s a small path toward…toward the solution we’re looking for. One small path: that both forms are forms of exteriority, at the very moment of exteriority of the condition/conditioned bond that the other can slide in. Yeah… it’s semi-convincing. Semi-convincing… Well, that’s okay, we’ll have to look elsewhere.

Simply, what do we remember from Roussel? He already made a lot of progress, and he helped us make a lot of progress toward the idea that there were mutual captures, even if we do not know how it occurs yet. There are mutual captures, that is, you do not extract statements without creating the visible; you do not extract visibilities without proliferating statements. The two forms are absolutely heterogeneous, but they are in mutual presupposition, there is a mutual capture. All right. This is what Foucault expresses in The Birth of the Clinic and Raymond Roussel, two books from the same period, one being the serious version of the other and the other being the humorous version… what Foucault summarizes by saying: “speaking and giving visibility at the same time.” You see, it’s very important, “speaking and giving visibility at the same time”: that means, and consider this: speaking and giving visibility, or speaking and seeing are two purely heterogeneous forms and yet there is an “at the same time”, the “at the same time” is mutual capture. In other words, our whole path of small solutions that are emerging…mutual capture is able to work precisely because mutual capture is not the capture of one form by another.

It is because everything happens as if there is not only a gap between the two forms, but it is as if a gap runs across each form: a gap between light and reflections, scintillations, etc., a gap between the “there is” of language and the statements disseminated in language. So, it is in this second type of gap that the insinuation is made. The visible seeps into the statement; it is the double insinuation. There’s an insinuation of the visible into the statable, an insinuation of the statable into the visible. Thanks to this, the two forms are two heterogeneous forms, yes, but two forms of exteriority. It is therefore the exteriority that defines each so that the other can seep in and slide in.

And, at the same time, I’ll say once again: it’s only semi-convincing. We are not happy with this solution. Because it doesn’t really get us out of this, but this violence… Of course, it bears repeating: there is also violence. So, to say that it is not, that the double capture is not the capture of one form by the other, but that it is an insinuation of something thanks to the function of exteriority proper to each of the two forms…But, after all, why should the exteriority of one form be penetrable by the other? You understand, we have the feeling… yes, we have taken a step forward, but it’s not yet… we’re not yet… we’re not happy. I guess we’re not happy. No.

And then, second point, Foucault finds another solution in Roussel. Because there is a third kind of work in Roussel. We saw two types of works: works of procedural language and works of visibility or vignettes. Then there is a third kind of work, even crazier than the other two combined that Roussel…that Roussel doesn’t talk about in How I Wrote Certain of My Books, which is perhaps his most beautiful work… it seems to me… well, no, not his most beautiful work… but he creates a very curious work called: New Impressions of Africa. So I’m telling you, the procedure here is completely different. The language procedure is completely different. I’m telling you this before investigating how it can serve us.

There we are: suppose you say a sentence, you say a sentence that is comprised of three lines, for example. I have my three lines… [Deleuze writes on the board] …There, there, there. And then, between the second and the third, I insert a parenthesis…. and there you go…. between the second and the third… I’m giving you the formal schema of the procedure before giving you an example, because, strangely enough, the example is even more obscure than…, since we can’t follow the sentence anymore, you can guess — So… I’m going to clean up because it’s not going to be big enough — [Pause while Deleuze cleans the board] Thank you… [He stays at the board] These are my three verses… no… [He writes on the board] They’re just any rhymes at all, that happens, right? Suppose that, between 2 and 3… this is the first version. Second version: between 2 and 3 you introduce a parenthesis, a two-line parenthesis. So, I put it in dotted lines. [He writes on the board] That changes everything, you have 1, 2, 3, 4 and what was 3 becomes 5…You understand everything from here. Why not go to infinity? Between 3 and 4 we’ll introduce a second parenthesis marked by double parentheses; [he’s at the board] let’s say you want to add a parenthesis here – I’m putting some color on there for you — a parenthesis of three verses.

Then suddenly, you have: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 4 becomes 6, 3 becomes 7. In your double parenthesis of two verses you can introduce, between the two verses, a third parenthesis symbolized like that, etc. etc. etc. You’re going to say: it’s annoying because we’re going to lose track. Yes, we’re going to lose track, but at the benefit of what disorientation, at the benefit of what poetic disorder! Foucault analyzes an example. Why isn’t he going to…? This is usually the case with an infinite work. I mean, when we talk about infinite work, it’s never good if it’s an image or a metaphor. If we talk about infinite work, well, we have to do it. If we don’t do it, it doesn’t amount to anything. At that moment we should not talk about an infinite work. I can say that Roussel invented an infinite work in concrete terms. So, he doesn’t have to do it because he entreats us to do it. He goes as far as…and besides, it’s very, very complicated, I… I’m only giving you the starting point of… of… Impressions of Africa.

Foucault gives an example… [Pause as Deleuze looks in his book] Here it is. “First version”. Only we don’t have the first version, it’s Foucault who restores the versions by removing the brackets. We’re going to take a look at the text. It still stops, uh… it usually stops, well, at most… it seems that at most, and I haven’t checked, but according to Foucault, the maximum is five parentheses. That’s already a lot. These are the successive versions. This is a first group of four verses. The first version: “Skimming the Nile, I see floating by two banks covered with flowers, wings, lightning, rich green plants, one of which would be enough for twenty of our salons, thick foliage, fruits and rays of light.” You see. It’s curious, by the way, that: “rich green plants, one of which would be enough for twenty of our salons”, a single green plant that is enough for twenty salons. A mystery. All right. This is the first version. “Skimming the Nile, I see floating by two banks covered with flowers, wings, lightning, rich green plants, one of which would be enough for twenty of our salons, thick foliage, fruits and rays of light.” We still have a stranglehold, we’re fine, we’re managing to keep up, already with a little bit of effort, but we’re managing to keep up.

We stop at the end of verse 3: “one of which would be enough for twenty of our salons.” And we’ll make a two-line parenthesis. Then we get:”…flowers, wings, lightning, rich green plants, one of which would be enough for twenty of our salons,” parenthesis: “gentle salons where as soon as we turned our heels on the one that moves away we make many noises run”… Close the parenthesis and you start again, you follow one another: “thick foliage, rays of light and fruits.” Already, we don’t really know where we stand anymore. So much so that the second version is: “Skimming the Nile, I see floating by two banks covered with flowers, wings, lightning, rich green plants, one of which would be enough for twenty of our salons, (gentle salons where as soon as we turned our heels on the one that moves away we make many noises run), thick foliage, rays of light and fruits.”

Well, suppose, on that point, that since I introduced two verses in the first parenthesis, I put a double parenthesis between the first and second verses of the first parenthesis. It would be: “gentle salons where as soon as we turned on our heels (by amusing ourselves either with his cowardice or his fine talents, whatever he does or says), on the one that moves away we make noises run.” Then you land again on: “…thick foliage, rays of light and fruits.” You keep going. You introduced the first line of the double parenthesis, which is “by amusing ourselves either with his cowardice or his fine talents, whatever he does or says.” You introduce a triple parenthesis after “by amusing ourselves either with his cowardice.”

This gives you: “gentle salons where as soon as we turned our heels (by amusing ourselves either with his cowardice (distinctive strengths no matter what we do or say to them, judging the senselessness of Talion, taking a greeting for an eye and a smile for a tooth) …” you keep going…. So, I can give you the final reading again, but… to see if you follow: “Skimming the Nile, I see floating by two banks covered with flowers, wings, lightning, rich green plants, one of which would be enough for twenty of our salons (gentle salons where as soon as we turned our heels on the one that moves away, we run…”, shit. Ah, I’m going to start again [Laughter]: “at twenty of our salons (gentle salons where as soon as we turned around (by amusing ourselves either with his cowardice or his fine tal…” ahh, I can’t do it, we should… I didn’t bring the text, but where there are all the parentheses, you see how it works. [Pause] I’m not going to reconstruct this… All right.

So, why do we care about that? What serious things can we get out of it – and again, seriousness is not better… there’s nothing better than that…it’s not worth doing again, right? That’s part of it… as they say, once someone has done it, you only have to do it once and that’s it. You have to find your… [Deleuze does not finish the sentence]

I would like to point out that when it is not the… that in a very interesting preface, Foucault considered, or drew a parallel between three great manipulators of language, uh… inventors of artificial languages, of heterodox languages, like that, uh… which includes Roussel, whose analysis he had taken up in a short preface to something else, [Jean-Pierre] Brisset, and a much more contemporary American named [Louis] Wolfson who, as they say, accomplishes something and invents a language completely different from that of Roussel, and what’s interesting about Foucault’s text is how he compares the three and tries to show everyone the diversity of their respective procedures. Roussel’s procedure, Brisset’s procedure, who is also a writer in the early 20th century, and Wolfson’s procedure, who is still living today, a young American who created a kind of invention, an invention of language and a completely bizarre use of language.

However, this would not turn out to be the only case, but when it came to Roussel, Foucault dedicated his deepest analyses to him. And I just want to point out what would be interesting and that, each time, there’s a battle, there’s an internal battle within language, there is the Roussel battle, the Brisset battle, and the Wolfson battle, plus all kinds of others… for those who are interested in this topic, you should refer to the, to the… there’s an entire problem of language and schizophrenia where the bibliography is endless but very, very important, very interesting and where you would find really great information on schizophrenic languages in the Art Brut Notebooks, in particular. Or we should go back to… no, yes, whatever.

So, this new procedure, this second solution, this proliferation of parentheses, why? And in the name of what can I claim to say: well, yes, it is a second solution. If you followed along today, I don’t know, it’s not that we’re laughing a lot, but it’s not that we’re laughing, and what I’m saying is different, it’s funny; everything I’m saying today is funny. It doesn’t make us laugh, but it’s funny. Like, it’s not that we see it, but it’s visible, right? That’s the way it is. It used to be serious. Well, what interests me is how the two ultimately change places with one another: the so-called comic analysis and the serious analysis, but they’re the same, you know. Because think about the procedure in the proliferation of parentheses. What does it mean? It means: the statement has determining power. Furthermore, the statement makes an infinite determination. The statement is infinite determination. What does “infinite determination” mean? Well, it’s pretty simple; infinite determination means that, and we can see it in concrete terms, you can always cause the parentheses that separates two parts of a given sentence, two sections of the sentence, to proliferate. It is a principle in the sentence, a principle of infinite determination. And it’s even a kind of practice where you’ll be able to make your loved ones find you irresistible when you talk like that.

Ah, well, a principle of infinite determination is specific to the statement. But why does that work for us? Let me remind you of our previous serious analyses. The form of the statement is determination or spontaneity. The form of the visible is receptivity. The “there is” of language is spontaneous, the “there is” of light is receptive. And we saw, after a long analysis that I am not going to repeat, how it could be said from this point of view that Foucault was Kantian. What I was trying to translate in saying that was the following: you know, the form of the visible is the form of the determinable while the form of the statement is the form of determination. And the two forms remained strictly irreducible to one another, which was Kant’s greatest contribution, as we saw… it seemed to us that Kant’s greatest contribution was showing that the form of the determinable was irreducible to the form of determination, and thus reproaching all his predecessors for not having seen it, for having believed that determination was all about the undetermined.

And Kant told us: not at all, determination necessarily concerns the determinable and not the indeterminate, and the determinable has a form, which is not the same as that of determination. There are therefore two irreducible forms: the form of the determinable and the form of determination. Thus, the question was: if there is a relationship between the visible and the statable, determination must bear on the determinable. But how can this be since the two forms are irreducible? How can determination bear on the determinable since the form of determination is irreducible to the form of the determinable and vice versa?

Do you see why I am interested in Roussel’s procedure? The answer would be: yes, but the form of determination goes to infinity. The form of determination goes to infinity. This is what The Archaeology of Knowledge says: there are discursive formations, statements, and then there is the non-discursive, there are only discursive relations—the non-discursive is not discursive, the two forms are heterogeneous—only the discursive has discursive relations with the non-discursive. All right. It is because determination goes to infinity that it can reconnect with the determinable from then on. That is why the level of Roussel’s procedure in New Impressions of Africa gives us the key to a relation between the two forms within the non-relation. Hmmm. Do you understand?

And why do we have the same qualms as we did before? No, this is not enough yet. It’s not enough yet, why? For a very simple reason: when determination goes on forever, what will keep the determined from slipping away indefinitely? And that’s what happens in Roussel’s final technique: you can’t see anything anymore. You can’t see anything anymore. Visibility is lost when determination wins. Visibility decreases as determination goes on to infinity. Foucault senses it, recognizes it in his own way when he talks about the “mad pursuit” in New Impressions of Africa; the mad pursuit that Roussel engages in when he wants to bring language to the level of infinite determination. But, at that moment, there were visibilities that fled with a vengeance. As the determination increases, visibility recoils.

Thus, our problem is still the same: okay, there is a battle, but the two must join forces, meet, and we are still saying: yes, everything will be explained if the two meet, but the two do not meet, the visible will not meet the statable, the statable will not meet the visible, and when faced with the prison, we will still be condemned to say: “this is not a prison,” and faced with the pipe: “this is not a pipe.”

Unless… well, we did everything we could; it’s just that we were stupid. We were stupid. Maybe we were looking for a solution where there wasn’t one. Ah, were we looking for a solution where there wasn’t one? Well, yes. Let’s get used to it. Since we did everything, we thought was possible. Now I can’t see anything else. We can’t see anything else. Huh? Well, that’s our fault. What told us that the solution would be found at the same level as the problem? It’s very common that when a problem is posed, its solution is discovered in a different dimension from its own. There is no reason to believe that a problem should be solved with elements included in the very conditions of the problem. We can even say that the solution is often found elsewhere. We made a mistake by hoping to find a solution to emerge on the same level that the problem was posed. We have to look for it, we needed to catch it somewhere else.[6]

How do I know that? Well, that’s the third and final way toward the solution. Mutual capture was the first way. Infinite determination was the second way. The third way is nothing at all: let’s look for another dimension to solve the problem. However, this is Kant’s way, as we have seen. When it comes to explaining how there can be a relation within the non-relation of receptivity/spontaneity, do you remember what he told us? There is a schema of the imagination, an absolutely mysterious and hidden dimension, which is not a form. It’s not a form. The schema is not a form. And, strangely enough, this schema, which is not a form, is, on one hand, adequate to space and time, i.e. to the form of the determinable and, and on the other hand, adequate to the concept, i.e. to the form of determination. The two forms, the determinable and determination, are irreducible, heterogeneous, but there is something that is homogeneous to one of the forms and to the other of the forms. Simply put, this other thing is not a form. How can something that is not a form be homogeneous to two forms that are not homogeneous between themselves? It’s a mystery. Well, Kant’s genius is that he’s trying to make us understand it. He tries to make us understand it, my problem is not, it’s not exposing like… it’s uh… I’ll ask: are we going to find an analogous move in Foucault? Do we need to invoke another dimension to cause a relation to surface from a non-relation?

Well, yes. Another way of asking this would be: in what dimension can the fighters, the combatants meet? Since we saw, in terms of mutual captures that there was a stranglehold. In what dimension does the encounter between the fighters take place? It’s not at the level of forms, forms are unrelated. Then we need another dimension. This other dimension must be non-formal. This is what Foucault is going to explicitly say, it seems to me, in two important passages. A passage from This Is Not a Pipe about Paul Klee. Why Paul Klee? Because Paul Klee is without a doubt the greatest painter who has ever confronted signs and figures. Or, if you prefer: writing — or the statement — and the visible figure. [Longue pause]

For example…, it’s not over yet, yeah, those who haven’t gone, you have to…I beg you, go see the exhibition “Klee and Music.”

A student: Louder!

Deleuze: Ah, I’m saying you have to — I was lowering my voice because I… I was giving you advice, it was a side comment — I was saying that those who hadn’t gone have to find the time to go see the “Klee and Music” exhibition in the Beaubourg museum. There, you will see, you will understand everything about the relation… I am thinking about the paintings, in particular… there are two small paintings that are the simplest examples of what I mean. There are two small paintings that are wonderful, two small… really small paintings. There are features of a landscape, then you have: trees, fences, tufts of grass, flowers etc. that are completely separate from each other, scattered, and they are put on a musical staff. What I’m saying seems easy, right? And, in fact, if I try to recount it for you, I, well, it wouldn’t be enough to make the landscape sing, to make the garden sing. By what a wonder! Now that is genius. He does that… I assure you: you can’t look at the two versions of Klee’s garden, put on musical staff, as a simple dissociation of the elements; it’s very simple as a procedure—once again, there are much more complex procedures—but Klee is the simplest of cases, without which you wouldn’t be captivated, but you are fascinated, you are fascinated, you are not going to move on to…the garden sings. How did he do it? Well, yes, well, I think he made the signs and figures completely permeate, but what? In a dimension other than that of the painting: music. Music. Klee is the painter-musician. There is another non-given dimension and here is where the garden sings. So be it. This is what Foucault says: “Klee’s letters and figures meet in a completely different space than that of the painting”, that is, they meet in a space that is no longer that of statements, nor that of visibilities, nor that of signs, nor that of figures. Well, that’s a brief indication.

In another text, in Foucault’s analysis of Nietzsche, [Pause] he says this about the fighters, in a passage that is thus vital to us, since that is our problem, he tells us… he comments on what the Nietzschean notion of emergence means. And he says: emergence refers to a place of confrontation. Well, so far so good. In other words, a place of confrontation: there are fighters; it is the fighters’ stranglehold. “Still we must be careful not to imagine it as a closed field” (you see in parenthesis there’s a denunciation of the form of confinement), “still we must be careful not to imagine it as a closed field where a struggle would take place, or a plane where opponents would be on equal terms.” That means that the encounter does not happen on a closed field, and he adds: “Rather, it is a non-place…”, “rather, it is a non-place, a pure distance…” “A pure distance,” what is a pure distance? For those who know a little in this field, it is a notion typically used in topology, which is independent of forms, completely independent of forms.

So, it is a non-place, it is not a place, it is a non-place, it is a pure distance, namely, “the fact that adversaries do not belong to the same space. No one is responsible for an emergence, no one can take glory in it, it always occurs in the interstice.” Well, all right, the encounter of the form of the visible and the form of the statable occurs in the interstice between the two forms, so it does not imply any mixing of the two forms. It’s in a volume in tribute to Jean Hyppolite; it’s Foucault’s article on Nietzsche, p. 156, by Presses Universitaires, Hommage à Jean Hyppolite [1971].[7]

A student: It’s no longer available.

Deleuze: It’s no longer available?

Another student: Yes, you can still find it.

Deleuze: You don’t need to find it, since I’m telling you about it. [Laughter] Ah. Yes.

So, what does that mean? Okay, there’s a non-relation between the two forms. From this non-relation a relation will emerge, but the relation that emerges is in another dimension from that of the two forms, it is in a non-formal dimension. We need a non-formal instance just like the… Kant had to invoke a schema of the imagination to account for the co-adaptation of the two forms, also in a non-formal dimension, different from that of the two forms to account for the co-adaptation of the two forms. What will it be? What will it be?

And, well, there you go… time to relax, take a break… what time is it?

Lucien Gouty: 11:05 am

Go take a break, okay, and make the most of it — don’t make us chase after you — 10 minutes! [Pause; interruption of the recording] [1:44:06]

… to draw conclusions, because I’m sure it hasn’t escaped you, but we only have one more session before the holidays, and it would be nice if we could finish the first axis of Foucault’s thought, that is, learning it within the trimester. But unfortunately, I’m afraid that unless I slow down a lot I’m going to have to start the second axis… it’s not a big deal. So, let’s draw some conclusions about knowledge and the need for another dimension, another axis.

First remark: at the end of this trimester, I can claim that the first axis of Foucault’s thought was introduced under the term “knowledge”. And why is this the first axis of Foucault’s thought? Because it is of course understood that there is nothing beneath knowledge, or before knowledge. Experience is knowledge, knowledge does not refer to a prior object or subject. Subject and object are variables of knowledge, internal variables of knowledge. It’s up to you to decide if this is idealism or not. Maybe the question doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t matter. In any case, it is under this title that everything is and already was knowledge, which allows Foucault to break away from a notion dear to vulgar phenomenology, namely: there is no wild experience.

On that note, I would like to point out that, among you, since no one has interjected, since at the end of our lesson, you aren’t orally intervening, which is very good, very good… on the other hand, many of you are passing me notes after what I said and up until now, notes of great interest, that is to say, they obviously come from people who know Foucault’s texts as well as I do or even better… uh.. and in these notes, which I will quote because I have had several passed to me…I caution those of you who wrote these notes not to believe that I am not interested in them—on the contrary, but I feel like I am not yet at a point where I can take them into account in my analysis, so I am saving them for the right time, at that moment I will again take up the topic that inspired the notes. Now one of you, in particular, gave me a note telling me: it is very nice to say that there is no wild experience in Foucault, but, in any case, that does not prevent him from using the expression “wild truth”, and, uh, the person who wrote this note cited texts to me… Well, when the time comes, we will have to ask ourselves: what is meant by Foucault’s affirmation that there are “wild truths”? Nevertheless, this implies a means of wild experience since truth is a matter of experience.

So, to approximate, I’ll say: if we stick to the first axis, there’s no place for a wild experience that would be like the soil that nourishes knowledge. Knowledge has no other nourishing ground than itself. So, the first reason why there is no wild experience at this level is that everything is knowledge and there is nothing before knowledge, nor beneath knowledge. So that’s our first set of conclusions. The second set, the second type of conclusion, is that knowledge has two parts…. [Interruption of the recording] [1:48:13]

Part 4

… even if he is less specific about visibilities in certain texts, to the point of giving them only a negative name, the non-discursive, as opposed to the discursive, it still seems that, even in this case, where this case is The Archaeology of Knowledge, it is noted that the non-discursive is irreducible to the discursive, which is to say that there is dualism. I would say: if there is dualism, don’t worry too much about it… Is there dualism? Yes, I would say: at this level there is dualism, knowledge is dual, and it is because of a lack of awareness of many thinkers who are even close to Foucault who seem to mutilate his thought. I have tried to say it – to only retain a theory of statements by not taking sufficient account of the status of light and the visible, which makes him a sort of new kind of analytic philosopher.

Well, so I think that there is dualism in terms of knowledge.[8] Only I would like to insist on quickly raising the question about the nature of dualism in general. What does it mean to be a dualist? Because, in my opinion, there are at least three dualisms. And there is only one of them that deserves the definitive title of dualism. The first kind of dualism is the real one. True dualism consists in saying: there are two, there are two and one is irreducible to the other. You can find this dualism, and if I look at authors who are truly dualistic, I would say that to my knowledge there are two in all. You can say: that’s not true, but, ultimately, that’s how I see it, it’s not a big deal. There is Descartes because, in Descartes, there is an authentic dualism between thought and extension, between the thinking substance and the extended substance, once we acknowledge that the third substance does not overcome the dualism of thought and extension at all. I would say: yes, in Descartes, there is an objective or substantive dualism. I see another one: it’s Kant, and this time it’s subjective dualism. There is dualism between two fundamental faculties which, as in Foucault’s case for knowledge, are the two constituent parts of knowledge: receptivity and spontaneity. Dualism is no longer between substances, but between the faculties of the subject, or dualism is no longer between attributes of substance, it is between the faculties of the subject, so that, from Descartes to Kant, there is a complete transformation from substance to subject. Well, that’s the first dualism.

I’d also say: there is a second kind of dualism which this time is a provisionary stage towards the One. Making two – dualism – is a means, a kind of stage towards one ultimate goal: discovering a more profound unity. I would say: this provisional dualism, [Pause] I see two examples, if we’re going to stick with two…it’s dualism after all… then, I could apply this to Spinoza. In Spinoza, there is indeed a real distinction, a dualism, between the attribute “thought” and the attribute “extended”. Only this dualism is a provisional stage towards the unity of substance which contains all attributes; it is a provisional stage towards the One.

A student: [Inaudible comments]

Deleuze: It’s a …

The student: [inaudible words] that’s not a dualism, there are [inaudible words] …

Deleuze: Yes, that… don’t complicate… don’t complicate what I’m saying, okay!… I’m just saying. It’s not… Yes, you’re right… No! Because actually, to the extent that there’s a single substance, I know that there’s an infinite number of attributes. I mean: the infinity of attributes is a consequence of the unity of substance, it is because there is only one substance that I know it cannot be satisfied by two attributes, i.e. infinity does not intervene here, infinity is a consequence of unity. What is important is the overcoming of attributes, you understand, towards a single substance from which we can conclude that there are an infinite number of attributes that are unknown to us.

The other case would be [Henri] Bergson. Bergson is famous for his dualisms. Duration and space, matter and memory, and even more: all his titles, “the two sources”, all his titles explicitly announce dualism. But, in Bergson’s case, as well, dualism is only a transitional step towards a triumphant monism. Namely: in the first stage, duration and substance are opposed… no, sorry, duration and space are opposed, there are two sources of morality and religion, matter and memory are opposed. In the second stage: the two opposite terms are the extreme degrees of the same instance, namely, space is only the most dilated degree of duration or space is only the most dilated degree of the élan vital and duration is only the most contracted degree of the élan vital. The same élan vital passes through the two dual forms, one being its extension or dilation, the other being its contraction. So, overcoming dualism must be traversed on the way to monism. You see.

There is a third kind of dualism, because, in the end, there is something very basic: speaking is always about having duels. The duel is inscribed in speech. The duel is inscribed in language. So you will always be a dualist in words. Simply put, the question of dualism is something that starts beyond words, namely: is this dualism a real dualism in your opinion, that is, a dualism that applies to things? Is it a “provisional stage” dualism, or what is it? I would say: there are cases where dualism is no longer a “provisional stage”, but like a preparatory stage. You are going to ask me: what’s the difference? A preparatory stage. A preparatory stage towards what? If I reflect towards what… a preparatory stage of what? If I ask myself “preparatory stage of what?” I think I will see the difference between the second dualism and the third one that I am talking about right now. It would be a preparatory stage of multiplicities, in other words, it would be a preparatory stage of pluralism. It’s no longer a provisional stage towards monism, towards the One, towards a unity, but a stage… what did I say? I don’t know anymore… a stage, a stage… a provisional… no, I don’t know anymore.

Several students: Preparatory.

Deleuze: Preparatory, yes, a preparatory stage of multiplicity and pure pluralism. That’s the one I’m interested in, this dualism, because what would that mean? Notice that my third dualism is opposed to the second, why? It’s because the notion of multiplicity, and I have always found this fascinating, is a noun. As long as you say “the multiple”, you haven’t said anything. As long as you use the adjective, you haven’t said anything because all you’ve done is add a slight animation to the One. Because, what is multiple if not one? In other words, you are, maybe, a Platonist, that’s already very good. All right. But, if you are Platonic, you are one of the large number of people who say: the multiple can only be used as an adjective. “Multiple” is an attribute. What a stroke of genius it was when, and you had to be German to do this, thinkers put the multiple in the form of a noun and constituted the notion of multiplicity: a multiplicity.

Note that a multiplicity is still strange because you would have to be a logician to comment on the “a”, the indefinite article, it is obvious that the indefinite article of “a multiplicity” cannot be the same as the indefinite article of “a man”. It wouldn’t be a small feat to turn the logic of the “a” into “a multiplicity”. It’s the indefinite article, it’s a non-unifying article. What happens when multiplicity turns into a noun? It means that it no longer refers to any unit, neither from which it would derive, nor to which it would initiate. It means: the multiple must be thought of by itself and in itself.

What would a multiple be? A multiplicity is “n – 1” (small n minus 1), it is not “n+1” because a multiplicity is what removes one from the multiple. Otherwise, a multiplicity would never be established. It’s always in subtracting the one that I get multiplicity. How to think of a multiplicity? Is a multiplicity something that can be thought about? Good. The only way to criticize the one is in the name of multiplicity. As long as I oppose the multiple to one, I have done nothing to disturb the one. If I show reasons why the multiple must be related to a multiplicity or multiplicities, then I can say: I destroyed the One. But I can’t claim to have destroyed the One until I’ve performed this operation that substantivizes the multiple. Does the multiplicity make sense?

The act by which the multiple has been erected as a substantive, that is, as a multiplicity, is a scientific act. I mean: I believe that the origin… I believe that the origin of the notion found in the great mathematician-physicist [Bernhard] Riemann and taken up by the mathematician [Georg] Cantor, at the basis of set theory. You will find it in [Edmund] Husserl, although Husserl is hardly a pluralist, but he uses this notion and it has intense scientific richness. I think Riemann is the one who gives this kind of gift to philosophy. A notion of multiplicity. Okay, we don’t know what a multiplicity is yet. I’m just saying it’s very close to Foucault’s thought. Why? If you understand everything that has just been said about the forms, the form of the visible and the form of the statable, then you understand that they are not units. I’m saying: these are conditions that disperse and disseminate statements. These are conditions that disperse and disseminate visibilities. Which is to say what? That is to say: you know, every statement is a multiplicity.