February 12, 1973

There is all this at the same time on the body without organs: the paranoid position of the mass, the schizo position of the pack, and I mean: packs, masses, all these types of multiplicity. The unconscious is the art of multiplicities; it is a way of saying that psychoanalysis understands nothing about anything since it has always treated the unconscious from the point of view of an art of units: father, mother, castration. Whenever psychoanalysts are faced with multiplicities — we have seen it about the Wolf Man for Freud — it is a question of denying that there are any multiplicities.

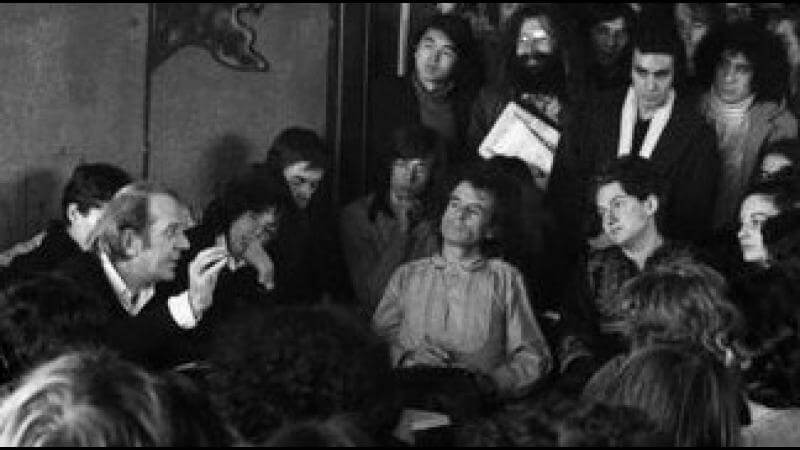

Seminar Introduction

With only five sessions available in this seminar, Deleuze continues to expand the concepts developed for Anti-Oedipus with the long view of the second volume, A Thousand Plateaus. Moreover, alongside these sessions, Deleuze alone and with Guattari develop texts for publication that correspond directly to the seminar: Deleuze’s conference presentation, ‘Nomadic Thought’ for the July 1972 conference ‘Nietzsche aujourd’hui?’ at Cerisy-la-Salle appears in 1973; second, Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘Bilan-Programme pour machines désirantes’ appears in Minuit 2 (January 1973), and then is included as an appendix to a revised edition of Anti-Oedipus (1975).

English Translation

Deleuze’s initial comment concerns his and Guattari’s goal of searching for the conditions of statements (énoncés) within, for example, psychoanalysis, i.e. regarding desire and the unconscious. Referring then to the previous session, he quickly shifts to how mass groupings or distributions function in relation to a subject’s trajectory on a body without organs, and he identifies the mass system as inscribing a network of signs on the body without organs as a territory. Deleuze points to two coexistent states of the sign, one paranoid, another freed from the signifier, and he maintains that these states correspond to two positions on the body without organs, a position of mass and a position of packs (meute). These two positions intersect in the unconscious, not in opposition, but in interplay within a bi-polar machinic apparatus, the mass machine as the signifying semiotic machine, hierarchized and egalitarian, on one hand, and on the other, the pack machine of particle-signs, types of Brownian movement, as the a-signifying semiotic machine. Deleuze examines Kafka’s love for Felice, an example of how one cannot know which apparatus might come to dominate in a given situation, mass or pack, with Kafka seeking to convert an Oedipus position into a writing machine (e.g., his Letter to the Father). Finally, Deleuze returns to the initial student question about schizo incest, stating that this incest opens the schizo to a world of connections and a kind of defamiliarization of the individual.

Download

Gilles Deleuze

On Anti-Oedipus II, 1972-1973

Session 1, 12 February 1973

BwO – Drugs – Signifier – Paranoia

Transcription: WebDeleuze; modified transcription, Charles J. Stivale and Christian Kerslake

Translated by Christian Kerslake

Kyril Ryjik: […] in incest in psychoanalysis and in anthropology, there is an aspect of incest that you leave aside, the place of which one does not see in schizo incest. So why the word ‘incest’ in that case?

Deleuze: To state the basic principle, it was a question of seeking what the conditions of statements [énoncés] were in general[1]; and after all, one could pose psychoanalysis under this form: what are the conditions of statements, supposing that statements have relations with desire, that is to say, with the unconscious? Statements are not at all the products of a system of signification; they are the product of machinic assemblages[2], they are the product of collective agents of enunciation. Which implies that there are no individual statements, and that behind statements – when for example one is able to assign some epoch where statements change, a historical epoch where a new type of statement is created, for example the great breaks of the Russian revolution type, or indeed of the phalanx type in the Greek city;[3] a new type of statement appears, and on the horizon of this type of statement there is a machinic assemblage that makes it possible, i.e. a system of political agents of enunciation. ‘Collective’ does not mean ‘people’, nor ‘society’, but something more [phrase missing – ‘like multiplicities’?].[4] We must seek in machinic assemblages that belong to the unconscious the conditions for the emergence of new statements, the bearers of desire, or what concerns desire.

Once again, it is no longer a question of opposing, like two poles, a pole that we would assign to paranoia, and a pole that we would assign to schizophrenia. On the contrary, it’s about saying that everything, absolutely everything, is part at the same moment of a machinic assemblage which is determinable, and we simply have to see how this assemblage is made insofar as it is productive of statements.

It seemed to me that every machinic assemblage literally hooked itself onto a certain type of body without organs. The question we are dealing with is: assuming that every machinic assemblage happens, hooks itself onto, mounts itself on a body without organs, how is that fabricated, a body without organs? What can serve this or that person as a body without organs? This is also the drug-user’s problem: how do they make it so that, assuming this is true, this really is a formation of the unconscious, upon which [phrase missing], and that it functions as a condition so that assemblages, connections, are established, so that there is something that one can call a body without organs? Groups are bodies without organs; political groups, community groups, etc., imply species of bodies without organs, sometimes imperceptible, sometimes perceptible, on which the entire machine assemblage that will produce statements will attach itself. The archetype of the body without organs is the desert. It is like the support, like the support of desire itself.

What is going to attach itself? In a schizoanalysis, the problem of the unconscious is not a problem of generations. [André] Green has dispatched an article on Anti-Oedipus, and he says: in any case, these guys are a bit dim, because they’re forgetting that a schizo still has a father and a mother.[5] Well, that’s just lamentable: listen to a schizo. A schizo has neither father nor mother, it’s so obvious. It is not as a schizo that he is born of a father and of a mother – a schizo, as schizo, has no father or mother, he has a body without organs. The problem of the unconscious is not a problem of generations, but of population.[6] What populates the body without organs, what makes assemblages, connections? Someone’s happiness is their own way of making bodies without organs. As a fundamental difference with psychoanalysis, I insist once again: we do not know in advance. This duff concept of regression, it’s a way of saying: what you are is your affair, at least in principle, we know it in advance, since what you are is what you are. While here it’s the opposite principle: you don’t know in advance what you are. It’s the same with accounts of drugs: you don’t know in advance.

There is a very beautiful book by a gentleman called [Carlos] Castaneda which recounts his apprenticeship in peyote with an Indian, and the Indian explains to him that whatever the case, you need an ally.[7] You need a benefactor to guide you in this apprenticeship, this is the Indian himself, but you also need an ally, that is to say something which has a power. In order to make yourself a body without organs – a very lofty task, a very sublime task – an ally is necessary, not necessarily someone else, but you need an ally which will be the point of departure for a whole assemblage capable of functioning on such a body.

We saw, last time, on this body without organs, a kind of mass distribution, phenomena of mass, of population.[8] Why do these organize themselves? Because the immediate effect of the body without organs is identical with the experience, the experimentation, of a depersonalization. What seems fascinating to me is that it is at the very moment of an attempt at depersonalization that one acquires the true meaning of proper names, that is to say, one receives one’s true proper name at the very moment of depersonalization. Why?

Let’s suppose that there are groupings of mass, these are not necessarily social masses, because here, in relation to the body without organs, as opposed to the organism of a subject, the subject itself gives itself over to crawling around on the BwO, to tracing spirals. It conducts its search on the body without organs like a guy walking about [se balade] in the desert. This is the test of desire. Like the Unnameable in Beckett, it traces its spirals.[9] It itself, as depersonalized on the BwO, even its very organs, which in so far as they are now related, not to its organism, but to the body without organs – they have all completely changed their relationships. Once again, the BwO is indeed a defection from the organism, the disorganization of the organism for the benefit of another instance; and this other instance, the organs of the subject, the subject itself, etc., are as if projected onto it, and enter into a new kind of relation with other subjects. All that takes shape like masses, pullulations, where, literally, on the body without organs, one no longer really knows who is who: my hand, your eye, a shoe. A camel on the BwO of the desert, a jackal, a man on the camel, that makes up a chain.

At this level, in any case, the mass inscribed on the body without organs delimits like a territory. The elements of mass, whatever they are, define signs. And what ensures the coherence, the connections between signs?

What defines the mass, it seems to me, is a whole system of networks between signs. Sign refers to sign. That’s the mass system. And it refers to the sign under the condition of a major signifier. Here we have the paranoid system. The whole force of Lacan is to have made psychoanalysis pass from the Oedipal apparatus to the paranoid machine. There is a major signifier which subsumes the signs, which maintains them in the mass system, which organizes their network. That seems to me to be the criterion of paranoid delirium: it’s the phenomenon of the network of signs, where sign refers to sign.[10]

Ryjik: You’re making some kind of description, it’s not very clear, but you’re describing something. And if there is the same collection without a signifier, what is that?

Deleuze: That’s next.

Ryjik: But does that form a network, or does it not form a network?

Deleuze: It forms a thread [enfilade], not a network.

It is necessary to see how this major signifier appears. The purely descriptive system says: there is a regime of the sign under the signifier, and this is the network such as we find it in paranoid delirium. This seems to me the first stage of what it would be necessary to call the deterritorialization of the sign. It’s when, on a territory, the sign, instead of being a sign as such, passes – Have you finished coughing up? It’s disgusting – passes under the domination of a signifier. Your question is substantial: where does this signifier come from?

Signs, in another mode altogether, follow trajectories of flight; there is all the same a concrete criterion. This time, it is no longer the sign referring to another sign in a network, it is a direction starting from which a sign enters into a linear thread [s’enfile] with other signs. As opposed to paranoid delirium, it is for example erotomaniac delirium[11], or grievance delusion.[12] All of this still happens on the BwO. The sign, this time, has liberated itself from the mortgage and domination of the signifier. In which form it liberates itself from it in order to become and take on the status of director, accelerator and retarder of particles.

The two coexisting states of the sign are: the paranoid sign, namely the sign under the signifier, forming a network insofar as it is subsumed by the signifier, and then: the sign-particle, liberated from the signifier and serving as teleguidance for a particle.

The body without organs is populated in a singular fashion. It is no longer masses, species of coexisting lines, that always traverse this desert, and that guide particles on coexisting lines that diverge and intersect. Anything is possible in things like this. It is no longer the mass phenomenon, it is the pack [meute] phenomenon. It’s not at all the same thing because the subject, i.e. this weird kind of thing which is sometimes in the mass, sometimes in packs, enters into connection under the form of a network with other subjects, other organs, but sometimes in accordance with its lines of flight, where it also enters into specific types of relationship with others, but in pack relationships and no longer ones of mass.

The huge difference between the position of mass and the position of pack is why I’m so interested in the Wolf Man, and Freud’s radical non-understanding. The position of mass is always a position affected with paranoid characteristics; this is all the less pejorative as for me, this year, it’s all about saying: long live paranoia, there is not enough of it, we need to fix that …

Ryjik: Well, that’s something different! [Laughter]

Deleuze: The paranoid position of mass is: I will be in the mass, I will not separate myself from the mass, and I will be at the heart of the mass, in two possible capacities: either as chief, and therefore having a certain relationship of identification with the mass – for the mass can be the grave[13], it can be an empty mass, it doesn’t matter; or as partisan where, in any case, it is necessary to be swept up in the crowd [masse], to be as close as possible to the crowd, with one condition: to avoid being on the edge [bordure]. It is necessary to avoid being on the edge, being on the margins, in the position of mass: to not be last, you have to be close to the chief. The border is a position that it is only possible to guarantee in a mass, so that when one is in service, one must be there.

Henri Gobard: On the problem of the edge: if one is on the inside, there is no edge … Everything you say is a kind of fantastic justification of anything whatever, in any way whatever, for anywhere wherever …

Richard Zrehen: … and for anyone whoever!

Gobard: Maybe not for anyone whoever, that’s the problem; in your desert, instead of putting a camel, put a white bear: what will happen? How would your analysis work on something which, to me, seems monstrous, truly worse than Nazism, if that’s possible: namely the transplantation of organs! Cardiac patients no longer have organs, an organ is transplanted into them, … I’m against it, because it leads to the transformation of bodies into systems of spare parts, and that is precisely the Nazi mentality of the concentration camps … [Christiaan] Barnard is a Nazi, and contemporary science, biology and medicine belongs to the Nazi type …[14]

A student: Why did you have to sit there next to Deleuze, instead of sitting at the back?

Gobard: No, no, if you had arrived earlier, you would have seen that I sat here in order to make a sounding board. Someone was making a recording; and secondly, because it was pissing me off with all the assholes smoking …[15]

Richard Zrehen: I was wondering whether the intensive powers on the body without organs, the thresholds of intensity, the energetic passages, if you like, whose schema has been borrowed from embryology, even if it is no longer just that, since it is all the same a serious basis, I wondered if there was not a way of ‘quantifying’ or ‘qualifying’ these thresholds, these passages, these fillings-up through intensive quantities, of the body without organs; and immediately, the only association I could make was the modification of colors indicating an intensity in the level of the cold or the heat given off, something like that. You just talked about statements which, visibly, on the body without organs, exactly fulfill, perhaps at another level, the foundation of intensive powers.

Deleuze: Yes, yes, yes, but I am so far from having finished. The intensities, I haven’t placed them on the inside yet, but I would see no reason to privilege colors or phenomena of hot or cold; localizations also count for a lot. The Wolf Man, his relationship with wolves, is absolutely inseparable from two bodily localizations, which are the jaw and the anus. The psychoanalyst who took over with the young man after Freud says that the Wolf Man says that one of his dentists keeps telling him: you have too hard a bite, your teeth will fall out.[16] There, we clearly see something of a kind of current of intensity: a higher intensity, the jaw-bite; the teeth too fragile for such a jaw-bite: lower intensity; and what we have there is a definite kind of passage of intensity between a minimum and a maximum, which is of a very particular type, of a localization type.

To return to the position of mass, one can say that there is no edge, for the simple reason that the problem of the mass is: to determine segregation and exclusion. There are simply falls and rises. The position of pack is completely different. Its essential character is that there is a border-phenomenon. The essential always happens at the edge. In the book Crowds and Power [Masse et Puissance] by [Elias] Canetti there is a very good description of the pack. He says something very important about the distinction between mass and pack (page 109): “In the pack which, from time to time, forms out of the group, and which most strongly expresses its feeling of unity” – that’s strange, that’s not true – “the individual can never lose itself as completely as modern man can in any crowd today. In the changing constellation of the pack …” – he, at least, understands wolves: in the pack each member guides itself through its companion, and at the same time, the positions never cease varying. They vary all the time, and they define themselves through distances. Distances between the members of the pack. Distances which are constantly variable and indecomposable. This is what makes it so that the pack is always distributed over, that the members of the pack are always on, a periphery. “In the changing constellation of the pack […], he will again and again find himself at its edge. He may be in the center, and then, immediately afterwards, at the edge again; at the edge and then back in the center. When the pack forms a ring round the fire” – that’s quite stirring, that bit – “each man will have neighbors to right and left, but no one behind him; his back is naked and exposed to the wilderness.”[17] This is absolutely the position of pack. I adhere to the pack through – so here, it is indeed another regime of organs, it is not a regime of networks – I adhere to the pack through a foot, a hand, a paw, through the anus, through an eye. This is the position of pack.

I add, there is all that at the same time on the body without organs: the paranoid [parano] position of mass, the schizo position of pack, and I mean: packs, masses, all these types of multiplicity. The unconscious is the art of multiplicities; this is a way of saying that psychoanalysis understands nothing at all since it has always treated the unconscious from the point of view of an art of unities: the father, the mother, castration. Every time psychoanalysts find themselves faced with multiplicities, as we have seen with the Wolf Man, it is a question of denying that there are multiplicities. Freud cannot bear the idea that there are six or seven wolves in the story of the Wolf Man; it is necessary that there is only one, because a single wolf, that’s the father. And the Wolf Man can cry all he likes: the wolves, the wolves, the wolves; Freud says: a single wolf, a single wolf, a single wolf.

These masses and these packs of the unconscious can just as well be existing groups, but these existing groups, for example, political groups, they also have an unconscious, an unconscious – and here, I’m saying at the same time – that’s why everything functions together. It is no longer a question of saying: let’s oppose paranoid/schizophrenic in a duality, because the same group has a mass unconscious and a pack unconscious as well. It lives off a whole system of signifying signs, under the signifier, but at the same time, it lives off a whole system of particle-signs which are its ways of getting the hell out, its ways of drifting. It is at once the most immobile bloc and simultaneously the most adrift thing there is. It is therefore at the same time that it is necessary to make all that function. To these two machinic poles apparatuses are added. If I try to define the two machinic poles which, for the moment, cover the bodies without organs, I would say that the one is the mass machine, which one could call the semiotic signifying machine: it is the system of signs under the domination of the signifier, and forming the paranoid network. The other machine, that of the sign-particles, the pack machine, is the semiotic a-signifying machine: it is the sign-particle system, the coupling of sign and particle. Each member of a pack is a particle, each particle could be anything; as a mass element, it could be anything.

So, upon that, apparatuses intervene that are certainly linked to these machines. And again, it’s not a question of saying: Oedipus does not exist. It’s about saying: there is only an Oedipal apparatus, and the Oedipal apparatus, it’s a funny thing, because it plays between the mass machines and the pack machines. Its whole play is between the two; it borrows elements from mass machines. I believe that the meaning of the Oedipal apparatus is to plug the flights of packs, to bring them back to the masses … I’m forgetting a lot of things in the current, but another distinction that it would be necessary to make between mass machines and those belonging to packs, would be that masses, at least in appearance, always present, at a certain moment, a phenomenon of unity of direction. They are simultaneously egalitarian and hierarchised. We must not at all say, like the Marxists, that egalitarianism is an ideological phenomenon, or that it is a certain formal phenomenon; it must be said that class organization, in historical formations, in its most diverse forms, has always been made in real relation – it does not at all belong to ideology – with some form of communitarian egalitarianism. Class organization in the bourgeois system is made in the form of a real equality determined under the conditions of capitalism. Class formation in the so-called despotic systems implies the real egalitarianism of rural communities. Class organization in the ancient city implies the victory of the plebs; that, as Engels says very well, implies a certain position of egalitarianism in relation to which slavery will be able to take place and be produced. So it is not at all opposed, that the mass structure is simultaneously an egalitarian structure, and that it is all the more strongly and more severely hierarchised, presenting a kind of unity of direction at every moment. Whereas the pack phenomenon is really what one calls Brownian motion; whenever there is a pack, you will find this kind of pattern traced on the body without organs.

The Oedipal apparatus is this strange thing that tries to plug these kinds of flights of particles, and which tries to lead them back. It is necessary to make the four things function in the machinic assemblage at the same time, and this is perhaps what produces the statements of the unconscious. There are counter-Oedipean apparatuses …

Ryjik: With what you were saying before, are you trying to say that the Oedipal apparatus has a privileged situation between the two?

Deleuze: No! No more than the counter-Oedipal apparatus. The counter-Oedipal apparatus must no doubt make the inverse manoeuvre; it will let packs loose. You understand, nobody knows in advance for anyone: what might seem most Oedipal, it could very well be that it’s a guy in the process of tipping over into an anti-Oedipal apparatus that will make everything crack. We will never say to someone: you are in regression. Never, never. Or else we will never say to him: you are this because you were that. First of all, it is disgusting, and then it is not true.

I resume. This love so strange of Kafka for Felice[18], what is going on in there? Well, Felice is everywhere. Kafka, what is he up to? First, he has his method … let’s suppose he has found a little something which can serve him as a body without organs. On it, he is in love with Felice. Kafka is all the same an executive, a future great bureaucrat, the whole machine of commerce fascinates him. His problem is once again the situation of the Jews in the Austrian empire; he is caught up in a problem of mass: the imperial mass of the Austrian empire which will precisely be described in The Castle in marvelous terms: when one is far from the castle, it is truly an imperial ensemble, it is a mass, and when one approaches the castle, it is much more like a system of hovels at a distance from each other, as if, to the extent that one approaches, the mass figure melts into a pack figure. And that corresponds very well to the Austrian empire which, experienced from within, is a kind of marquetry, not at all a pyramidal system, but rather a kind of segmentary system. He is caught up in all that, with modern machines, work accidents. He had connections with anarchist circles. The political mass, the imperial mass, the commercial mass, the bureaucratic mass, that’s what he’s concerned with. It is obviously impossible to separate Felice from what she is as well. Kafka, however, takes her for a maid, and it turns out that Felice is not a maid. So here is Felice, who has a certain position in a mass structure, and at the same time, she has big carnivorous teeth, which attracts and disgusts Kafka. He is vegetarian and will cease being vegetarian from the moment of his love affair with Felice; he is fascinated by the idea of teeth between which, in which bits of meat remain, he’s got a weird thing about it.[19] One of Kafka’s fundamental problems is: where does [missing word – ‘food’][20] come from, and this is undoubtedly connected to a position of the body without organs … and these huge carnivorous teeth, that’s another side of it. It is the particle which makes Felice escape, which tears her in some way from the imperial bureaucratic technocratic signifier, makes her break loose onto a completely different line, where, this time, the sign of the big teeth, or rather the Felice-sign, guides, accelerates, and precipitates huge teeth particles, which are set racing in the other coexisting system. Thereupon, third element. Of course, there is Oedipus, and this is Kafka’s problem: how am I going to manage, in the situation I’ve put myself, to not marry Felice? She wants marriage, while he sets his extraordinary conditions: this, this, this. She wants a family right away, she paints him a picture of marriage, it is an innocent one: she wants a homestead, you’ll eat meat everyday …; he faints. Kafka has a habit of turning tricks like that, and it’s fantastic, because that explains the existence of Marthe Robert.[21] There’s a proof of the existence of Marthe Robert for you. Kafka always played a formidable game with his father. His father never stopped winding him up, it’s true: there is therefore an Oedipal statement; but moving quickly, what did Kafka tell himself?

He said to himself what we need to say to ourselves today about paranoia, but he said it to himself at the level of Oedipus. In the prodigious letters to his sister who had a child, he says that this kid must not be left in the family, he has to get the hell out of there.[22] And for his part, in order to ward off Oedipal statements – because they do exist – he will ward them off in the form: transform the Oedipal statement into an enunciation-machine for making letters.

Once again, there is no freedom, there are ways out. If one wants freedom, one is asking too much: then one is lost and it’s all fucked in advance. What is needed is to find ways out, and Kafka’s way out is: my father is winding me up, so I’m going to write to him. That will always be the Kafkian way out, converting Oedipus into a writing machine. It is a great idea; and so he writes his famous letter to his father. It is a way out because, thanks to the writing machine, he can add: in other words, I am going to be more Oedipal than you. Exactly as with the paranoiac, one has to succeed at being more paranoid than him. This is why we have to revalorize the paranoid: the only defense against the paranoiac is even more paranoia.

So Marthe Robert says: you can clearly see how Oedipal he is. Necessarily, he doesn’t stop ladling it on in order to make all Oedipean statements pass into the enunciation of a writing machine that is apparently Oedipal, but in fact is anti-Oedipal, that is to say which is going to splinter Oedipal connections in favor of a system of connections of a perverse writing machine. Once he pulls this off with his father, you know it’s going to work like that even more with the women he loves.

Felice offers him conjugality, that is to say, the adult form of Oedipus. Very quickly, he will counter with the parade he put into effect so well with his father. He is never able to come and see her where she is, because it is necessary that he writes to her; that’s the insurance against conjugality. He sends her all manner of letters, he can only love through letters; he sets conditions, conditions of conditions, etc. In all of that, it is the whole of Oedipus and the whole problem of conjugality that is dissolved, to the benefit of something else altogether.

Anything can work like that. Everything that one puts on the side of the Oedipal apparatus, namely incest, castration, the vacation letter (“My dear Dad, my dear Mum, I am having a lovely holiday”), anything at all, can pass into non-Oedipal apparatuses. And a whole analysis is necessary to arrive at knowledge; that’s why there is always hope. Homosexuality can be like [missing word], completely Oedipal from one end to the other. It all depends on the use; it can pass into other conditions, into an anti-Oedipal apparatus of an entirely different nature.

When I speak of a schizo incest, as making up part of an anti-Oedipal apparatus, ie. incest with the sister – but the sister can be anyone, – Oedipal incest is love with someone assimilated with the mother in one way or another; schizo incest is love with someone somehow assimilated with the sister. The passage from Oedipal incest to schizo incest is like a conversion, a transformation of the Oedipal apparatus into an anti-Oedipal apparatus, which means that schizo incest is what opens onto a kind of world of connections and which will lead, literally, to a kind of de-familiarization of the individual. Now, it may very well be that there are incests with the sister which are Oedipal, to the extent that the sister would be treated as the substitute for the mother.[23]

In order to finish with all this, I would like, just as a bit of a proof, to comment on a text by Kafka, ‘Jackals and Arabs.’[24] One can see very well why he mixes everything up, why he sets traps. In ‘Jackals and Arabs’, we can say that everything is there, for Freud or for Marthe Robert. There are the Arabs who explicitly belong to the male line; and then there are the jackals which are explicitly attached to the maternal line. Right at the beginning, the jackal says: “we have been waiting for you for eternity; my mother waited for you, and her mother, and all our foremothers right back to the first mother of all the jackals.”[25] Between the jackals and the Arabs, there is, on the edge, the man of the North, that is to say the Jackal Man. It’s only Freud who doesn’t know what a pack of wolves is. The jackals take the man of the North aside and say to him that the Arabs are disgusting, and they’re disgusting because they kill animals for food. They kill calves to eat. That’s really Kafka’s fundamental obsession: where does food come from?

The jackals say that it can’t continue, because they are against it; they say: us, we’re the opposite: we eat to clean up carrion. So: either kill living animals to eat, or eat to clean up dead animals. Hence the Arab-jackal tension. Now the man of the North shows up and the jackals say to him: you’re going to kill the Arabs; and they bring a large pair of rusty scissors. I won’t stop to dwell on what the psychoanalysts are able to make of these scissors. All this is happening in the desert. The Arabs are presented as an armed mass, extended throughout the desert. The jackals are presented as a pack that goes deeper and deeper into the desert, which is forced to plunge deeper and deeper into the desert: mad particles. And at the end of the text, the Arab says about the jackals: “they’re madmen, complete madmen.”[26] And the jackals reveal the secret of the story of the scissors – the man of the North was ready to say: you want me to kill them, but the jackals aren’t interested in that: it’s a question of cleanliness, it’s the test of the desert. That means that, in this kind of tension, the Arab mass, the pack of jackals, a manifest Oedipal apparatus and a counter-Oedipal apparatus, will put in play the test of desire under the form: it is a question of cleanliness.

Once these four elements are given, what will happen, if I am granted that every statement is the product of an assemblage? How might we define a statement as the product of a machinic assemblage? It goes without saying that all that is indeed the problem of unconscious, i.e. that an analysis which does not reach multiplicities, a double type of multiplicities, multiplicities of mass and multiplicities of packs, which are now in a double way what an individual participates in, as well as being what is internal to an individual – well, we can say that the analysis has not even begun. When one has not reached the edge-positions, the paranoiac positions of mass, the type of anti-Oedipal apparatus someone is in the process of setting up, their Oedipal apparatus, one has got absolutely nowhere near the formations of the unconscious – and above all when one does not know what assemblage is involved, and how it functioned for them and in them, that is to say, what type of statement it was capable of producing; and types of statements, when necessary, which are very far from what happens in the unconscious.

This is the problem of multiplicities, to put each thing into play in the others, like multiplicities of multiplicities. It is this analysis of multiplicities as being simultaneously exterior and interior to the individual that must be achieved, otherwise one has attained nothing of the unconscious. [End of the session]

Notes

[1] The term énoncé can be translated as ‘statement’ or ‘utterance’. In this Seminar, Deleuze is playing off various contemporary uses of the term énoncé, e.g., in Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge (translated by A.M. Sheridan-Smith, London: Tavistock, 1972 [1969]); in Jean-Pierre Faye, Théorie du Récit [Theory of Narrative] (Paris: Hermann, 1972) (discussed in the fourth and fifth sessions of this Seminar); and in Jacques Lacan’s opposition between the sujet de l’énoncé [‘subject of the statement’] and the sujet de l’énonciation [‘subject of enunciation’]; cf. Lacan, ‘The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire’, in Écrits (translated by Bruce Fink et al., New York: W.W. Norton, 2006 [1966]), pp. 800-802 [French pagination].

[2] The term agencement has no exact English translation, and might be translated as ‘arrangement’, ‘layout’, ‘configuration’, or ‘assemblage’. The last-named term is used here, but it should be borne in mind that the French term carries connotations of agency and activation that are absent from the English ‘assemblage’.

[3] Cf. Marcel Detienne, ‘La phalange. Problèmes et controverses’, in Jean-Pierre Vernant, Problèmes de la guerre en Grèce ancienne (Paris – La Haye: Mouton and Co., 1968), discussed in A Thousand Plateaus (translated by Brian Massumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987 [1980]), pp. 399 and 560 n.78.

[4] Cf. A Thousand Plateaus, p. 37: “There are no individual statements, there never are. Every statement is the product of a machinic assemblage, in other words, of collective agents of enunciation (take “collective agents” to mean not peoples or societies but multiplicities).” The missing French phrase would be comme multiplicités. Much of the material developed in this session finds its way into this plateau, ‘1914: One or Several Wolves’, in A Thousand Plateaus (pp. 26-38).

[5] André Green’s review of Anti-Oedipus, ‘À quoi ça sert’, was published in Le Monde on 28 April 1972, and then republished in expanded form in the Revue française de psychanalyse, vol. 36(3), 1972, pp. 491-499. Deleuze is presumably referring to the closing passage: “The whole book is based on the assertion that the schizo does not play Oedipus and rejects our system. Does this mean that he has neither father nor mother? Can we affirm that the schizo, in his psychosis, maintains no relationship with the imago of his progenitors? The whole of experience and theory are against this” (Revue française version, p. 499).

[6] In the article, Green claims that “Anti-Oedipus is the negation of the double difference (of the sexes and generations)” (ibid, p. 497).

[7] Carlos Castaneda, The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972 [1968]). On the ‘ally’, see pp. 9, 32-34. For discussions of Castaneda in A Thousand Plateaus, cf. pp. 227-229, 248-249.

[8] The reference to the “last session” points to the existence of a session (or sessions) prior to this one. The final session of the first Seminar on Anti-Oedipus (18 April 1972) ends with a discussion of the body without organs, but there is no discussion of ‘masses.’ Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power (translated by Carol Stewart, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973 [1960]) is not mentioned in the first Seminar, nor is the idea of ‘mass’ thematized. However, Canetti’s distinction between crowds and packs is briefly mentioned in Anti-Oedipus itself (translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1983), p. 279, where it is discussed in relation to paranoia (with a reference to the closing chapter of Crowds and Power, ‘Rulers and Paranoiacs’). Crowds and Power was originally entitled Masse und Macht in German (1960) and was translated into French as Masse et puissance (Paris: Gallimard, 1966). In German, Freud’s Group Psychology is Massenpsychologie. The term ‘mass’ in the present Seminar often means ‘crowd’, and its use can be related to themes in the first part of Canetti’s Crowds and Power, ‘The Crowd’, pp. 15-87. See the discussion of masses and packs in A Thousand Plateaus, p. 33-34.

[9] Cf. Samuel Beckett, The Unnameable, in Trilogy (London: Picador, 1979 [1959]): “I must have got embroiled in a kind of inverted spiral” (p. 290); “I’ve never left the island, God help me. I was under the impression I spent my life in spirals round the earth” (p. 300).

[10] In a discussion of early 20th century psychiatry in A Thousand Plateaus (pp. 119-120), singling out the work of Paul Sérieux and Joseph Capgras on the one hand and Gaëtan de Clérambault on the other, Deleuze and Guattari develop a contrast between a “paranoid-interpretive ideal regime of significance”, which they associate with ‘delusion [or delirium] of interpretation’, and a “passional, postsignifying subjective regime”, associated with ‘passional’ delusions like erotomania and grievance delusion [délire de revendication]. It is likely that this distinction also has a source in Lacan’s extensive discussion of Sérieux and Capgras’ work Les Folies raisonnantes [Reasoning Madness] (1st ed. 1906), along with Clérambault’s work and other related works from the French school, in his doctoral thesis De la psychose paranoiaque dans ses rapports avec la personnalité [On Paranoid Psychosis in its Relations with the Personality] (Paris: Seuil, 1975 [1932]), pp. 64-76. Delirium of interpretation is twice described there as “radiating” out from a central delusion (p. 67; cf. 71). Lacan in turn roots Sérieux and Capgras’ account of paranoid interpretation in Kraepelin’s classic formulation of paranoia as “the insidious development, under the dependence of internal causes and according to a continuous evolution, of a durable and unshakable delirious system [système délirant], and which is established with a complete retention of clarity and of order in thought, will and action” (first given in the 1899 edition of his Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie) (Lacan, p. 23). Deleuze’s formulation here of paranoid interpretation as involving networks in which ‘sign refers to sign’ seems to arise out of this context.

[11] Lacan, De la psychose paranoiaque dans ses rapports avec la personnalité, pp. 24 and 72 (where Clérambault’s work on erotomania is discussed).

[12] There is no exact English translation for the French term revendication, frequently used in Lacan’s 1932 dissertation on paranoid psychosis and common among the French psychiatrists he discusses. Délire de revendication is sometimes translated into English as ‘litigious delusion’, sometimes more literally as ‘delusion of claim’. The translation ‘grievance delusion’ has a greater extension than ‘litigious delusion’ (which is more suited to the specific phenomenon of vexatious litigation).

[13] Possibly a reference to Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power, ‘Cemeteries’, p. 275.

[14] The transcript of this passage ends with the non-word “esclaruerunt …?”

[15] A note in the WebDeleuze transcript adds: “Nota Bene: Richard III, on this day, had no ‘havana’ at his disposal.”

[16] Ruth Mack Brunswick, ‘A Supplement to Freud’s History of an Infantile Neurosis’ (1928), republished in Muriel Gardiner (ed.) The Wolf-Man by the Wolf-Man (New York: Basic Books, 1971), p. 277: “The dentist now told him […] that he had a ‘hard bite’ and would soon probably lose not only the fillings, but all his teeth as well.” With regard to the anus, see Sigmund Freud, ‘From the History of an Infantile Neurosis’ (The ‘Wolf Man’), chapter VII, ‘Anal Erotism and the Castration Complex’.

[17] Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power, p. 109, cited in A Thousand Plateaus, p. 33-34.

[18] Franz Kafka, Letters to Felice, edited by Erich Heller and Jürgen Born, translated by James Stern and Elisabeth Duckworth, New York: Schocken Books, 1973). Elias Canetti published a guide to the voluminous letters, Kafka’s Other Trial: The Letters to Felice (translated by Christopher Middleton, London: Calder and Boyars, 1974 [1969]). See Deleuze and Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (translated by Dana Polan, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986 [1975]), pp. 29-34, and A Thousand Plateaus, p. 36.

[19] Kafka, Letters to Felice, p. 355.

[20] That ‘food’ is the missing term is made clear in a later paragraph. Cf. also Deleuze and Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, p. 20.

[21] In Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, Deleuze and Guattari criticise Marthe Robert’s annotations to the French 1963 Cercle du livre précieux critical edition of Kafka’s Oeuvres complètes for introducing “a psychoanalytical Oedipal interpretation” (p. 92, cf. 93), but praise her “excellent study” on Kafka, ‘Citoyen de l’utopie’, Les Critiques de notre temps et Kafka (Paris: Garnier, 1973) (p. 95). Robert’s 1979 book-length study of Kafka, Seul comme Kafka was published in English as Franz Kafka’s Loneliness (translated by Ralph Manheim, London: Faber & Faber, 1982).

[22] See Kafka’s letters of 1921 to his sister Elli, in Franz Kafka, Letters to Friends, Family, and Editors (translated by Richard and Clara Winston, New York: Schocken, 1977).

[23] On schizo incest in Kafka, see Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, pp. 66-68. On incest with the sister in anthropology, see Anti-Oedipus, pp. 159, 200.

[24] Franz Kafka, ‘Jackals and Arabs’, in Wedding Preparations in the Country and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970), pp. 129-132; cited in A Thousand Plateaus, p. 37.

[25] Kafka, ‘Jackals and Arabs’, p. 129 (translation modified).

[26] Kafka, ‘Jackals and Arabs’, p. 132 (translation modified).

French Transcript

La séance est évidemment un fragment, dominé par la discussion entre Deleuze and quelques participants. Beaucoup des concepts considérés seront développés dans Mille Plateaux, notamment le corps sans organes, le signifiant et le paranoïa.

Download

Gilles Deleuze

Sur L’Anti-Œdipe II, 1972-1973

1ère séance, 12 fevrier 1973

CSO-Drogue-Signifiant-Paranoia

Transcription : WebDeleuze et Le Terrier; transcription modifiée, Charles J. Stivale et Christian Kerslake

Kyril Ryjik : […] Dans l’inceste en psychanalyse et en anthropologie, il y a une note d’inceste que tu abandonnes, dont on ne voit pas la place dans l’inceste schizo. Alors pourquoi le mot “inceste” dans ce cas-là ?

Deleuze : Comme principe de base à proposer, il s’agissait de chercher qu’elles étaient les conditions des énoncés en général, et que après tout, la psychanalyse, on pouvait la poser sous cette forme : qu’est-ce que c’est que les conditions des énoncés, à supposer que les énoncés aient des rapports avec le désir, c’est-à-dire avec l’inconscient ? Les énoncés, ce n’est pas du tout les produits d’un système de signification ; c’est le produit d’agencements machiniques, c’est le produit d’agents collectifs d’énonciation. Ce qui implique qu’il n’y a pas d’énoncés individuels, et à l’arrière des énoncés, quand par exemple on peut assigner telle époque où les énoncés changent, une époque historique où un nouveau type d’énoncé se créé, par exemple les grandes coupures du type la révolution russe, ou bien du type la phalange dans la cité grecque ; un nouveau type d’énoncé apparaît, et à l’horizon de ce type d’énoncé, il y a un agencement machinique qui le rend possible, i.e. un système d’agents politiques d’énonciation. « Collectif », ça veut dire ni peuple, ni société, mais quelque chose de plus [mot qui manque]. Il faut chercher dans les agencements machiniques qui appartiennent à l’inconscient, les conditions de surgissement d’énoncés nouveaux, porteurs de désir, ou concernant le désir.

Encore une fois, il ne s’agit plus du tout d’opposer comme deux pôles, un pôle qu’on assignerait à la paranoïa, et un pôle qu’on assignerait à la schizophrénie. Il s’agit, au contraire, de dire que tout, absolument tout, fait partie à un même moment, d’un agencement machinique qui est déterminable, et il faut simplement voir comment cet agencement se fait en tant qu’il est producteur d’énoncés.

Il me semblait que tout agencement machinique, à la lettre, s’accrochait sur un certain type de corps sans organes. La question qu’on traite, à supposer que tout agencement machinique se passe, s’accroche, se monte sur un corps sans organes, comment ça se fabrique, un corps sans organes ? Qu’est-ce qui peut servir à telle ou telle personne, de corps sans organes ? C’est aussi le problème des drogués; comment font-ils, à supposer que ce soit vrai, que ce soit bien une formation de l’inconscient, sur laquelle des [mot qui manque] et que c’est comme une condition pour que des agencements, des connections s’établissent, qu’il y ait une telle qu’il puisse appeler corps sans organes. Les groupes, ce sont des corps sans organes ; les groupes politiques, les groupes communautaires, etc., impliquent des espèces de corps sans organes, parfois imperceptibles, parfois perceptibles, sur lesquels tout l’agencement de machine qui va être producteur d’énoncés va s’accrocher. L’archétype du corps sans organes, c’est le désert. Il est comme le support, ou comme le support du désir lui-même.

Qu’est-ce qui va s’accrocher ? Dans une schizo-analyse, le problème de l’inconscient, ce n’est pas un problème de générations : [André] Green a envoyé un article sur l’Anti-Oedipe, et il dit : “quand même, c’est des pauvres types, parce qu’ils oublient qu’un schizo, ça a quand même un père et une mère”. Alors là, c’est lamentable, écoutez un schizo. Un schizo n’a ni père ni mère, c’est tellement évident. Ce n’est pas en tant que schizo qu’il est né d’un père et d’une mère, un schizo, en tant que schizo, n’a pas de père ou de mère, il a un corps sans organes. Le problème de l’inconscient, ce n’est pas un problème de générations, mais de population. Qu’est-ce qui peuple le corps sans organes, qu’est-ce qui fait les agencements, les connections ? Le bonheur de quelqu’un, c’est sa manière à lui de se faire des corps sans organes. Comme différence fondamentale avec la psychanalyse, j’insiste encore une fois : on ne sait pas d’avance. Cette saleté de concept de régression, c’est une manière de dire : ce que tu es est ton affaire, au moins en droit, on la sait d’avance, puisque ce que tu es, c’est ce que tu es. Tandis que là, c’est le principe opposé, vous ne savez pas d’avance ce que vous êtes. C’est pareil pour les histoires de drogues : vous ne savez pas d’avance.

Il y a un très beau livre d’un monsieur qui s’appelle [Carlos] Castaneda, qui raconte son apprentissage du peyotl avec un indien, et l’indien, lui explique que de toutes manières, il faut un allié. [A ce propos, voir Mille plateaux, pp. 199-200 ; le premier livre de Castaneda est L’herbe du diable et la petite fumée (1971 ; Paris : Éditions du Soleil noir) ; cité dans le contexte décrit ici est Histoires de pouvoir (1974)] Il faut un bienfaiteur pour te mener dans cet apprentissage, c’est l’indien lui-même, mais aussi il faut un allié, c’est-à-dire quelque chose qui a un pouvoir. Pour se faire un corps sans organes, tâche très haute, tâche très sublime, il faut un allié, pas forcément quelqu’un d’autre, mais il faut un allié qui va être le point de départ de tout un agencement capable de fonctionner sur un tel corps.

On a vu, la dernière fois, sur ce corps sans organes, une espèce de distribution de masse, les phénomènes de masse, de population. Ils s’organisent pourquoi ? Parce que l’effet immédiat du corps sans organes, ça ne fait qu’un avec l’expérience, l’expérimentation d’une dépersonnalisation. Ce qui me paraît fascinant, c’est que c’est au moment même d’une tentative de dépersonnalisation, que on acquiert le vrai sens des noms propres, c’est à dire on reçoit son vrai nom propre au moment même de la dépersonnalisation. Pourquoi ?

Supposons qu’il y ait des groupements de masse, ce n’est pas forcément des masses sociales, c’est que, par rapport au corps sans organes, dans sa différence avec l’organisme d’un sujet, le sujet lui-même, voilà qu’il se met comme à ramper sur le CSO, à tracer des spirales. Il mène sa recherche sur le corps sans organes, comme un type qui se balade dans le désert. C’est l’épreuve du désir. Il trace, comme l’innommable dans Beckett, il trace ses spirales. Lui-même, en tant que dépersonnalisé sur le CSO, ou bien ses propres organes, qui en tant qu’ils sont rapportés maintenant, non pas à son organisme, mais au corps sans organes, ils ont complètement changé de rapports. Encore une fois, le CSO, c’est bien la défection de l’organisme, la désorganisation de l’organisme au profit d’une autre instance; et cette autre instance, les organes du sujet, le sujet lui-même, etc., est comme projeté sur elle, et entretient avec d’autres sujets, un nouveau type de rapports. Tout ça forme comme des masses, des pullulements, ou, à la lettre, sur le corps sans organes, on ne sait pas très bien qui est qui : ma main, ton œil, une chaussure. Un dromadaire sur le CSO du désert, un chacal, un bonhomme sur le dromadaire, ça fait une chaîne.

A ce niveau, de toutes manières, la masse inscrite sur le corps sans organes délimite comme un territoire. Les éléments de masse, quels qu’ils soient, définissent des signes. Et qu’est-ce qui assure la cohérence, les connections entre signes ?

Ce qui définit la masse, il me semble, c’est tout un système de réseaux entre signes. Le signe renvoie au signe. Ça, c’est le système de masse. Et il renvoie au signe sous la condition d’un signifiant majeur. C’est ça le système paranoïaque. Toute la force de Lacan, c’est d’avoir fait passer la psychanalyse de l’appareil œdipien à la machine paranoïaque. Il y a un signifiant majeur qui subsume les signes, qui les maintient dans le système de masse, qui organise leur réseau. Ça me paraît le critère du délire paranoïaque, c’est le phénomène du réseau de signes, où le signe renvoie au signe.

Ryjik : Tu décris, on ne sait pas très bien, mais tu décris. Et si il y a une même collection sans signifiant, c’est quoi ?

Deleuze : C’est la seconde.

Ryjik : Mais ça forme réseau ou ça ne forme pas réseau ?

Deleuze : Ça forme enfilade, et non pas réseau.

Il faut voir comment apparaît, ce signifiant majeur. Le système purement descriptif dit : il y a un régime du signe sous le signifiant, et c’est le réseau tel qu’on le trouve dans le délire paranoïaque. Ça me paraît le premier stade de ce qu’il faudrait appeler la déterritorialisation du signe. C’est lorsque, sur un territoire, le signe, au lieu d’être signe tel quel, passe – tu as fini de cracher ? C’est dégoûtant — passe sous la domination d’un signifiant. Ta question est pleine, d’où vient ce signifiant ?

Les signes, sur un tout autre mode, suivent des trajectoires de fuite, il y a quand même un critère concret. Cette fois-ci, ce n’est plus le signe renvoie au signe dans un réseau, c’est une direction à partir de laquelle un signe s’enfile comme linéairement avec d’autre signes. Par opposition au délire paranoïaque, c’est par exemple le délire érotomaniaque, ou bien le délire de revendication. Tout ça se passe toujours sur le CSO. Le signe, cette fois-ci s’est libéré de l’hypothèque et de la domination du signifiant. Sous quelle forme s’en est-il libéré pour devenir et pour prendre un statut de directeur, accélérateur, retardateur de particules.

Les deux états coexistants du signe, c’est : le signe paranoïaque, à savoir le signe sous le signifiant, formant réseau en tant que subsumer par le signifiant, et puis : le signe – particule, libéré du signifiant et servant comme de téléguidage à une particule.

Le corps sans organes se peuple singulièrement. Ce ne sont plus des masses, espèces de lignes coexistantes, qui traversent toujours ce désert et qui guident des particules sur des lignes coexistantes, divergeantes et s’entrecroisant. Tout est possible dans des trucs comme ça. Ce n’est plus le phénomène de masse, c’est le phénomène de meute. Ce n’est pas du tout pareil parce que le sujet, i.e. cette espèce de drôle de chose qui, tantôt est dans la masse, tantôt est dans les meutes, entre en connection sous forme de réseau avec d’autres sujets, d’autres organes, tantôt d’après ses lignes de fuite, où il entre aussi dans un type de rapports particuliers avec les autres, mais dans des rapports de meute et non plus de masse.

La grande différence entre la position de masse et la position de meute, c’est pourquoi m’intéresse tellement l’homme aux loups et la non compréhension radicale de Freud. La position de masse, c’est toujours une position affectée de caractères paranoïaques; c’est d’autant moins péjoratif que pour moi, il s’agit cette année de dire : vive la paranoïa, il n’y en a pas assez, faut arranger ça …

Ryjik : Ben, voilà autre chose ! [Rires]

Deleuze : La position paranoïaque de masse, c’est : je serai dans la masse, je ne me séparerai pas de la masse, et je serai au cœur de la masse, à deux titres possibles : soit à titre de chef, donc ayant un certain rapport d’identification avec la masse, car la masse peut être la tombe, elle peut être masse vide, peu importe ; soit à titre de partisan où, de toute manière, il faut être pris dans la masse, être au plus près de la masse, avec une condition : éviter d’être en bordure. Il faut éviter d’être en bordure, d’être en marge, dans la position de masse : ne pas être le dernier, il faut être près du chef. La bordure n’est qu’une position qu’il est possible d’assurer dans une masse, que lorsqu’on est en service, qu’il faut être là.

Henri Gobard : Sur le problème de la bordure, si on est dedans, il n’y a pas de bordure … Tout ce que tu dis, c’est une espèce de justification fantastique du n’importe quoi, dans le n’importe comment, au profit du n’importe où … [Henri Gobard écrit L’Aliénation linguistique : analyse tétraglossique (Paris : Flammarion, 1976) dont Deleuze écrit la préface, « Avenirs de linguistique », Deux régimes de fous (Paris : Minuit, 2003)]

Richard Zrehen : Pour n’importe qui !

Gobard : Peut-être pas pour n’importe qui, c’est là le problème; dans ton désert, au lieu de mettre un dromadaire, met-toi un ours blanc, qu’est-ce qui va arriver ? Comment fonctionnerait ton analyse sur quelque chose qui, à moi, me semble monstrueux, vraiment pire que le nazisme, si c’est possible, à savoir la transplantation des organes !! Les cardiaques n’ont plus d’organes, on leur en transplante un, … moi je suis contre, parce que ça aboutit à la transformation des corps en systèmes de pièces détachées, et c’est exactement la mentalité nazie des camps de concentration … Barnard est un nazi, et la science, la biologie et la médecine actuelle est de type nazi … esclaruerunt …??

Un étudiant : Pourquoi est-ce que tu t’es mis là, à côté de Deleuze, au lieu de te mettre au fond ?

Gobard : Non, non, si tu étais arrivé tout à l’heure, tu aurais vu que je me suis mis là pour faire une caisse de résonance. On a passé un enregistrement et, deuxièmement, parce qu’on me fait chier avec tous les connards qui m’enfument …

[Dans la transcription de WebDeleuze : Nota Bene : Richard III, ce jour, n’avait point de “havane” à sa disposition.]

Richard Zrehen : Je me posais la question de savoir si les puissances intensives sur le corps sans organes, les seuils d’intensités, les passages énergétiques, si tu veux, dont le schème a été emprunté à l’embryologie, même si ce n’est plus ça, parce que c’est quand même une base sérieuse, je me demandais s’il n’y avait pas un moyen de “quantifier” ou de “qualifier” ces seuils, ces passages, ces remplissages par des puissances intensives, du corps sans organes; et immédiatement, la seule association que j’ai pu faire, c’était des qualifications de couleurs, ressortir une intensité au niveau du froid ou de la chaleur qu’elle dégage, quelque chose comme ça. Tu es venu parler d’énoncés qui, visiblement, sur le corps sans organes, remplissent exactement, peut-être à un autre niveau, la fondation des puissances intensives.

Deleuze: Oui, oui, oui, mais je suis si loin d’avoir fini. Les intensités, je ne les ai pas encore placées là-dedans, mais je ne verrais aucune raison de privilégier les couleurs ou les phénomènes de chaud ou de froid, les localisations comptent beaucoup aussi. L’homme aux loups, son rapport avec les loups, c’est absolument inséparable de deux localisations corporelles qui sont la mâchoire et l’anus. La psychanalyste qui a repris le gars après Freud, dit que l’homme aux loups raconte qu’un de ses dentistes ne cesse pas de lui dire : vous avez un coup de mâchoire trop fort, vos dents tomberont. Là, on voit bien quelque chose d’une espèce de courant d’intensité, une intensité supérieure : mâchoire, les dents trop fragiles pour un tel coup de mâchoire : intensité inférieure et là, il y a une espèce de passage d’intensité défini entre un minimum et un maximum, qui est d’un type très particulier, d’un type localisation.

Pour en revenir à la position de masse, on peut dire qu’il n’y a pas de bordure, pour la simple raison que le problème de la masse, c’est : déterminer la ségrégation et l’exclusion. Simplement, il y a des chutes, des remontées. La position de meute est complètement différente. Son caractère essentiel, c’est qu’il y a un phénomène de bordure. L’essentiel se passe toujours en bordure. Il y a dans le livre Masse et Puissance de [Elias] Canetti [1960 ; Paris : Gallimard, 1966] une très bonne description de la meute. [Voir à ce propos Mille plateaux, pp. 46-47] Il dit quelque chose de très important sur la distinction masse et meute (page 97) : “Dans la meute, il se constitue de temps en temps, à partir du groupe, et exprime avec la plus grande force le sentiment de son unité” — ça c’est bizarre, ce n’est pas vrai — “l’individu ne peut jamais se perdre aussi complètement qu’un homme moderne dans n’importe quelle masse. Dans les constellations changeantes de la meute” – lui, au moins, comprend les loups, dans la meute chacun se guide sur son compagnon, et en même temps, les positions ne cessent pas de varier. Ça varie tout le temps, et ils se définissent par des distances. Les distances entre les membres de la meute. Des distances qui sont constamment variables et indécomposables. C’est ce qui fait que la meute est toujours répartie sur, et que le membres de la meute sont toujours sur un pourtour. “Dans les constellations changeantes de la meute, l’individu se tiendra toujours à son bord. Il sera dedans, et aussitôt après en bordure, en bordure et aussitôt après, dedans. Quand la meute fait cercle autour de son feu – c’est très émouvant ça -, chacun pourra avoir des voisins à droite et à gauche, mais le dos est libre. Le dos est exposé découvert à la nature sauvage.” C’est tout à fait la position de meute. Je tiens à la meute par – alors là, c’est bien un autre régime d’organes, ce n’est pas un régime de réseaux, je tiens à la meute par un pied, une main, une patte, par l’anus, par un œil. C’est la position de meute.

J’ajoute, il y a tout ça en même temps sur le corps sans organes : la position parano de masse, la position schizo de meute, et je veux dire: les meutes, les masses, tous ces types de multiplicité. L’inconscient, c’est l’art des multiplicités ; c’est une façon de dire que la psychanalyse ne comprend rien à rien puisqu’elle a toujours traité l’inconscient du point de vue d’un art des unités : le père, la mère, la castration. Chaque fois que les psychanalystes se trouvent devant des multiplicités, on l’a vu à propos de l’homme aux loups, il s’agit de nier qu’il y a des multiplicités. Freud ne peut pas supporter l’idée qu’il y ait six ou sept loups dans l’histoire de l’homme aux loups; il faut qu’il y en ait qu’un, parce que un seul loup, c’est le père. Et l’homme aux loups a beau crier les loups, les loups, les loups, Freud dit : un seul loup, un seul loup, un seul loup.

Ces masses et ces meutes de l’inconscient, ça peut aussi bien être des groupes existants, mais ces groupes existants, par exemple, des groupes politiques, ils ont aussi un inconscient, un inconscient — et là, je dis à la fois –, c’est pour ça que tout fonctionne ensemble. Il ne s’agit plus de dire : opposons dans une dualité paranoïaque/schizophrénie, parce qu’un même groupe a un inconscient de masse et aussi un inconscient de meute. Il vit de tout un système de signes signifiants, sous le signifiant, mais en même temps, il vit tout un système de signes particules qui sont ses manières de foutre le camp, ses manières de dériver. C’est à la fois le bloc le plus immobile, et à la fois le truc le plus à la dérive qui soit. C’est donc en même temps qu’il faut faire fonctionner tout ça. A ces deux pôles machiniques, il s’ajoute des appareils. Si j’essaie de définir les deux pôles machiniques qui, pour le moment, recouvrent le corps sans organes, je dirais que l’un, c’est la machine de masse qu’on pourrait appeler la machine sémiotique signifiante : c’est le système des signes sous la domination du signifiant, et formant le réseau paranoïaque. L’autre machine, celle des signes-particules, la machine de meute, c’est la machine sémiotique a-signifiante : c’est le système signe-particule, le couplage du signe et de la particule. Chaque membre d’une meute, c’est une particule, chaque particule, ça peut être n’importe quoi; comme un élément de masse, ça peut être n’importe quoi.

Alors, là-dessus, interviennent des appareils qui sont sûrement liés à ces machines. Et encore, il ne s’agit pas de dire : Œdipe, ça n’existe pas. Il s’agit de dire : il n’y a qu’un appareil œdipien, et l’appareil œdipien, c’est un drôle de truc parce qu’il joue entre les machines de masse et les machines de meute. Il a tout son jeu entre les deux ; il emprunte les éléments aux machines de masse. Je crois que le sens de appareil œdipien, c’est colmater les fuites de meutes, les ramener aux masses … J’oublie beaucoup de choses dans le courant, mais une autre distinction qu’il faudrait faire entre les machines de masse et celles de meute, ce serait que les masses, au moins en apparence, elles présentent toujours, à un moment, un phénomène d’unité de direction. Elles sont à la fois égalitaires et hiérarchisées. Il ne faut pas dire du tout comme les marxistes, que l’égalitarisme, c’est un phénomène idéologique, ou que c’est un certain phénomène formel ; il faut dire que l’organisation de classe, dans les formations historiques, sous ses formes les plus diverses, s’est toujours faite en rapport réel – ce n’est pas du tout de l’idéologie –, avec une forme quelconque d’égalitarisme communautaire. L’organisation de classe dans le système bourgeois se fait sous forme d’une égalité réelle déterminée dans les conditions du capitalisme. La formation de classe, dans les systèmes dits despotiques, implique réellement l’égalitarisme des communautés rurales. L’organisation de classe dans la cité antique implique la victoire de la plèbe, ça, Engels le dit très bien, i.e. une certaine position d’égalitarisme par rapport à laquelle va pouvoir se faire et se produire l’esclavage. Donc, ce n’est pas du tout opposé que la structure de masse soit à la fois une structure égalitaire, et qu’elle soit le plus fortement et le plus sévèrement hiérarchisée, et qu’elle présente une espèce d’unité de direction à tout moment. Tandis que le phénomène de meute, c’est vraiment ce qu’on appelle les mouvements browniens, chaque fois qu’il y a meute, vous trouverez cet espèce de tracé sur le corps sans organes.

L’appareil œdipien, c’est ce drôle de truc qui essaie de colmater ces espèces de fuites particulaires, et qui essaie de les ramener. Il faut faire fonctionner dans l’agencement machinique les quatre choses à la fois, et c’est peut-être ça qui est producteur des énoncés de l’inconscient. Il y a les appareils contre-œdipiens …

Kyril : Est-ce qu’avec ce que tu disais avant, tu essaies de dire que l’appareil œdipien a une situation privilégiée entre les deux ?

Deleuze : Non ! Pas plus que l’appareil contre-œdipien. L’appareil contre-œdipien doit faire sans doute le rabattement inverse ; il fait filer : meutes. Vous comprenez, personne ne sait d’avance pour personne : ce qui peut paraître le plus œdipien, il se peut très bien que le type soit en train de le faire basculer dans un appareil anti-œdipien qui va tout faire craquer. On ne dira jamais à quelqu’un : tu es en régression. Jamais, jamais. Ou bien on ne lui dira jamais : tu es ceci parce que tu étais cela. D’abord, c’est dégueulasse, ensuite ce n’est pas vrai.

Je reprends. Cet amour si étrange de Kafka pour Félice, qu’est-ce qui se passe là-dedans? [Sur Kafka et Félice, voir Mille plateaux, pp. 49-50] Eh bien, Félice est partout. Kafka, qu’est-ce que c’est son affaire à lui ? D’abord, il a sa méthode … supposons qu’il ait trouvé un petit quelque chose sur ce qui peut lui servir à lui de corps sans organes. Là-dessus, il est amoureux de Felice. Kafka, c’est quand même un cadre, un futur grand bureaucrate, toute la machine de commerce le fascine, son problème c’est encore une fois la situation des juifs dans l’empire autrichien; il est pris dans un problème de masse : la masse impériale de l’empire autrichien qui sera précisément décrite dans Le Château en termes merveilleux : quand on est loin du château, c’est vraiment un ensemble impérial, c’est une masse, et quand on s’approche du château, c’est beaucoup plus un système de masures à distance les unes des autres, comme si, à mesure qu’on s’approche, on faisait fondre la figure de masse en une figure de meute. Et ça répond très bien à l’empire autrichien qui, vécu du dedans est une espèce de marqueterie, pas du tout un système pyramidal, mais plutôt une espèce de système segmentaire. Il est pris là-dedans, les machines modernes, les accidents du travail, il était très lié avec des milieux anars. La masse politique, la masse impériale, la masse commerciale, la masse bureaucratique, c’est son affaire à lui. Felice, il est évident qu’elle est impossible à séparer de ce qu’elle est aussi. Or, Kafka la prend pour une bonne, et il s’avère que Felice n’est pas une bonne. Voilà donc Felice, qui a une certaine position dans une structure de masse, et en même temps, elle a de grandes dents carnivores, ce qui attire et dégoûte Kafka. Il est végétarien et il cessera d’être végétarien au moment de ses amours avec Felice; il est fasciné par l’idée de dents entre lesquelles, dans lesquelles restent des bouts de viande, c’est ses trucs à lui. Un des problèmes fondamentaux de Kafka, c’est : d’où vient la [mot qui manque], et c’est sans doute lié à une position de corps sans organes … et ces grandes dents de carnivore; ça, c’est l’autre aspect. C’est la particule qui fait fuir Felice, qui l’arrache en quelque sorte au signifiant impérial bureaucratique technocratique, la fait fuir sur une tout autre ligne, où, cette fois-ci, le signe les grandes dents, ou plutôt le signe Felice, guide, accélère, précipite les grandes dents particules, et la voilà qui file dans l’autre système co-existant. Là-dessus, troisième élément. Bien sûr, il y a Œdipe, et c’est le problème de Kafka : comment je vais faire, dans la situation où je me suis mis pour ne pas épouser Felice. Elle veut le mariage, alors il pose ses extraordinaires conditions : ceci, ceci, ceci. Elle veut tout de suite la famille, elle lui fait un tableau du mariage, c’est une innocente … elle veut un foyer, tu mangeras de la viande tous les jours, il s’évanouit. Il a l’habitude, Kafka, de tourner ces trucs-là, et ça, c’est joyeux parce que ça explique l’existence de Marthe Robert. Je vous donne une preuve de l’existence de Marthe Robert. Kafka a toujours joué avec son père un jeu formidable. Son père n’a pas cessé de l’emmerder, c’est vrai : il y a donc un énoncé œdipien, mais assez vite, Kafka, il s’est dit quoi ?

Il s’est dit ce qu’il faut que nous nous disions aujourd’hui pour la paranoïa, mais il se l’est dit, lui, au niveau d’Œdipe. Dans des lettres prodigieuses à sa sœur qui a un enfant, il dit qu’il ne faut pas laisser ce gosse en famille, il faut qu’il foute le camp. Et pour son compte, pour conjurer les énoncés œdipiens, parce qu’il y en a, il va les conjurer sous la forme : transformer l’énoncé œdipien en une machine d’énonciation à faire des lettres.

Encore une fois, il n’y a pas de liberté, il y a des issues. Si on veut la liberté, on en demande beaucoup trop, alors on est paumé et c’est foutu d’avance. Ce qu’il faut, c’est trouver des issues, et son issue à Kafka, c’est : mon père m’emmerde, je vais lui écrire. Ce sera toujours l’issue kafkaïenne ça : convertir Œdipe en machine d’écriture. C’est une grande idée; et il fait sa fameuse « Lettre au père ». C’est une issue parce que, grâce à la machine d’écriture, il peut en rajouter, à savoir, je serai plus œdipien que toi. Exactement comme avec le paranoïaque, il faut arriver à être plus paranoïaque que lui; c’est pour ça qu’il faut revaloriser le paranoïaque : la seule défense contre le paranoïaque, c’est encore plus de paranoïa.

Alors, Marthe Robert dit : vous voyez bien comme il est œdipien. Forcément il ne cesse pas d’en rajouter pour faire passer tous les énoncés œdipiens dans l’énonciation d’une machine d’écriture d’apparence œdipienne, et en fait, anti-œdipienne, c’est-à-dire qui va faire craquer les connections œdipiennes au profit d’un système de connections d’une machine perverse d’écriture. Une fois qu’il tient ce coup-là avec son père, vous pensez que ça marche encore plus avec les femmes aimées.

Félice lui propose la conjugalité, c’est-à-dire la forme adulte d’Œdipe. Très vite, il va lui opposer sa parade qu’il a bien mis au point avec son père. Il ne pourra jamais la voir où elle est puisqu’il faut qu’il lui écrive, ça c’est une assurance contre la conjugalité. Il lui envoie toutes sortes de lettres, il ne peut l’aimer que par lettres, il pose des conditions de conditions, etc. Dans tout ça, c’est tout Œdipe et tout le problème de la conjugalité qui se dissout au profit de tout autre chose.

Tout peut marcher de cette manière. Tout ce que l’on met du côté de l’appareil œdipien, à savoir l’inceste, la castration, la lettre de vacances, “mon cher papa, ma chère maman, je passe de bonnes vacances”, n’importe quoi, peut passer dans des appareils non oedipiens. Et il faut toute une analyse pour savoir ; c’est pour ça qu’il y a toujours de l’espoir. L’homosexualité peut être comme au [mot qui manque], complètement oedipienne d’un bout à l’autre. Tout dépend de l’usage ; elle peut passer dans d’autres conditions, dans un appareil anti-œdipien d’une tout autre nature.

Quand je parlerai d’un inceste schizo, comme faisant partie d’un appareil anti-œdipien, c’est-à-dire l’inceste avec la sœur — mais la sœur, ça peut être n’importe qui –, l’inceste œdipien c’est l’amour avec quelqu’un assimilé avec la mère d’une manière ou d’une autre. L’inceste schizo, c’est l’amour avec quelqu’un assimilé d’une manière ou d’une autre avec la sœur. Le passage de l’inceste œdipien à l’inceste schizo est comme une conversion, une transformation d’appareil œdipien en appareil anti-œdipien ; ça veut dire que l’inceste schizo est celui qui ouvre sur une espèce de monde de connections et qui va entraîner, à la lettre, une espèce de défamiliarisation de l’individu. Maintenant, il se peut très bien qu’il y ait des incestes avec la sœur qui soient œdipiens, dans la mesure où la sœur serait traitée comme substitut de la mère.

Pour en finir avec tout ça, je voudrai, juste un peu comme preuve, commenter un texte de Kafka : “Chacals et Arabes” [Voir Mille plateaux, pp. 50-51]. On voit très bien pourquoi il mélange tout, pourquoi il tend des pièges. Dans “Chacals et Arabes”, on peut dire que tout y est, pour Freud ou pour Marthe Robert. Il y a les Arabes qui sont explicitement à la ligne mâle; et puis il y a les chacals qui sont explicitement rattachés à la ligne mère. Dès le début, le chacal dit :”il y a une éternité que nous t’attendions, ma mère t’attendait, et sa mère et toutes les mères, en remontant jusqu’à la mère de tous les chacals”. Entre les chacals et les Arabes, il y a en bordure l’homme du nord, c’est à dire l’homme aux chacals. Il n’y a que Freud qui ne sait pas ce que c’est qu’une horde de loups. Les chacals prennent à part l’homme du nord et lui disent que les Arabes, c’est dégoûtant, et c’est dégoûtant parce qu’ils tuent les bêtes pour manger. Ils tuent les veaux pour manger. Ça c’est vraiment l’obsession fondamentale de Kafka : d’où vient la nourriture?

Les chacals disent que ça ne peut pas continuer parce qu’ils sont contre ; ils disent : nous, on est le contraire : on mange pour nettoyer les charognes. Donc, ou bien tuer les bêtes vivantes pour manger, ou bien manger pour nettoyer les bêtes mortes. D’où la tension Arabes-chacals. Il y a l’homme du nord qui est là et les chacals lui disent : tu vas tuer les Arabes, et ils emmènent une grande paire de ciseaux rouillés. Je n’insiste même pas sur ce que les psychanalystes peuvent faire avec ces ciseaux ; tout ça se passe dans le désert. Les Arabes sont présentés comme une masse armée étendue dans tout le désert. Les chacals sont présentés comme une meute qui va de plus en plus loin dans le désert, qui est forcée de s’enfoncer de plus en plus dans le désert, des particules folles. Et, à la fin du texte, l’Arabe dit à propos des chacals : ce sont des fous, des vrais fous. Et les chacals disent le secret de l’histoire lorsqu’ils disent, avec l’histoire des ciseaux, l’homme du nord est tout prêt à dire : vous voulez que je les tue, et les chacals, ça, ça ne les intéresse pas. C’est une question de propreté, c’est l’épreuve du désert. Ça veut dire que, dans cette espèce de tension, la masse arabe, la meute des chacals, un appareil oedipien manifeste et un appareil contre-oedipien, va se jouer l’épreuve du désir sous la forme : c’est une question de propreté.

Une fois donnés ces quatre éléments, qu’est-ce qui va se passer, si on m’accorde que tout énoncé est le produit d’un agencement ? Comment est-ce qu’on pourra définir un énoncé comme produit d’un agencement machinique ? Il va de soi que tout ça, c’est bien le problème de l’inconscient, i.e. qu’une analyse qui n’atteint pas aux multiplicités, double type de multiplicités, aux multiplicités de masse et aux multiplicités de meutes, qui, à nouveau d’une manière double, sont celles auxquelles un individu participe, et sont aussi bien intérieures à un individu, et bien, on peut dire que l’analyse n’a même pas commencé. Quand on n’a pas atteint les positions de bordures, les positions paranoïaques de masse, le type d’appareil anti-oedipien que quelqu’un est en train de monter, son appareil oedipien, on n’a absolument touché à rien des formations de l’inconscient, et quand on n’a pas su surtout quel agencement, et comment ça fonctionnait pour lui et chez lui, c’est à dire quel type d’énoncé c’était capable de produire, et des types d’énoncés au besoin très loin de ce qui se passe dans l’inconscient.

C’est ce problème des multiplicités à faire jouer les unes dans les autres, comme des multiplicités de multiplicités. C’est cette analyse des multiplicités comme étant à la fois extérieures et intérieures à l’individu, qu’il faut atteindre sinon on n’a rien atteint de l’inconscient. [Fin de la séance]

For archival purposes, the original transcript was prepared by WebDeleuze, with a modified version prepared in February 2023. However, the transcripts have been updated (in June 2023) based on the alternate and, in fact, complete transcripts available at Le-Terrier.net (http://www.le-terrier.net/index2.html). While the session 2 translation was prepared for WebDeleuze, the other four translations of each session were completed (in September 2023) for the Deleuze Seminars as well as revised descriptions.